Female Fighters Fight Toward Equal Footing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Views an Unjust Reason to Cancel

Page 8 FORUM Wednesday, April 28, 2021 Political views an unjust reason to cancel Today’s and criticism to Disney and Reporter, a source from Generation contributed to recent debates Lucasfilms said, “They have Hallie Funk on “cancel culture.” been looking for a reason to fire Several celebrities, actors, her for two months, and today and political figures have been was the final straw.” The “final Last October, actress Gina involved in these series of straw” was when Carano posted Carano stepped onto the “cancelling,” including Ellen a tweet that compared Jewish Disney+ screen as Cara Dune, DeGeneres, J.K. Rowling, and people in the Holocaust to the new female lead of the Johnny Depp. An individual is Republicans in America’s current hit show, The Mandalorian. typically “canceled” when the political climate. Although this As the season started, many public or media disagrees with is an extreme comparison that praised her acting abilities and a certain decision or belief the is not truly accurate, it is not accepted Carano as the perfect person has and chooses to stop a fireable offense. Her general cast for the role. She brought supporting them. It can be a point was not inappropriate, body positivity to the screen, result of accusations, negative but the Holocaust comparison and portrayed women as strong media coverage, or social media was. Which brings to question, and independent. But as of last posts, as in Carano’s case. are inappropriate comparisons month, she will no longer be a The controversy began back fireable offenses? part of Disney or her employing in November when Carano In June 2018, Pedro Pascal, agency. -

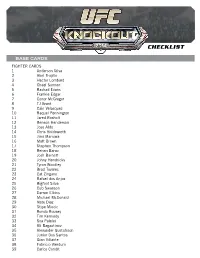

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

Absolute Championship Berkut History+Geography

ABSOLUTE CHAMPIONSHIP BERKUT HISTORY+GEOGRAPHY The MMA league Absolute Championship Berkut was founded in early 2014 on the basis of the fight club “Berkut”. The first tournament was held by the organization on March 2 and it marked the beginning of Grand Prix in two weight divisions. In less than two years the ACB company was able to become one of three largest Russian MMA organizations. Also, a reputable independent website fightmatrix.com named ACB the number 1 promotion in our country. 1 GEOGRAPHY BELGIUM The geography of the tournaments covered GEORGIA more than 10 Russian cities, as well as Tajikistan, Poland, Georgia and Scotland. 50 MMA tournaments, 8 kickboxing ones HOLLAND POLAND and 3 Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournaments will be held by the promotion by the end of 2016 ROMANIA TAJIKISTAN SCOTLAND RUSSIA 2 OUR CLIENT’S PORTRAIT AGE • 18-55 YEARS OLD TARGET AGE • 23-29 YEARS OLD 9\1 • MEN\WOMEN Income: average and above average 3 TV BROADCAST Tournaments are broadcast on TV channels Match!Fighter and BoxTV as well as online. Average audience coverage per tournament: - On TV - 500,000 viewers; - Online - 150,000 viewers. 4 Media coverage Interviews with participants of the tournament are regularly published in newspapers and on websites of leading Russian media: SPORTBOX.RU, R- SPORT.RU, CHAMPIONAT.COM, MMABOXING.RU, ALLFIGHT.RU , etc. Foremost radio stations, Our Radio, Rock FM, Sport FM, etc. also broadcast the interviews. 5 INFORMATION SUPPORT Our promotion is also already well known outside Russia. Tournament broadcasts and the main news of the league regularly appear on major international websites: 6 Social networks coverage THOUSAND 400 SUBSCRIBERS 4,63 MILLION VIEWS 7 COMPANY MANAGEMENT The founder of the ACB league is one of the most respected citizens of the Chechen Republic – Mairbek Khasiev. -

Co-Operative Republic of Guyana National Sports Policy (NSP)

Co-operative Republic of Guyana National Sports Policy (NSP) 2019 Respect SPORTS Equity Fair Play GUYANA Integrity 1. Table of Contents 1. Table of Contents------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- pg. 1-2 2. Executive Summary --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- pg. 3 3. Definition of Policy ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- pg. 4 4. Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- pg. 5 5. Historical Narrative ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- pg. 6-7 6. Philosophy --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- pg. 8-11 6.1 Vision ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- pg. 9 6.2 Mission------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ pg. 10 6.3 Values ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 [email protected] PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype A

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype After a five-month hiatus, the legendary promotion Pancrase sets off the summer fireworks with a stellar mixed martial card. Studio Coast plays host to 8 main card bouts, 3 preliminary match ups, and 12 bouts in the continuation of the 2020 Neo Blood Tournament heats on July 24th in the first event since February. Reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, Isao Kobayashi headlines the main event in a non-title bout against Akira Okada who drops down from Featherweight to meet him. The Never Quit gym ace and Bellator veteran, Kobayashi is a former Pancrase Lightweight Champion. The ripped and powerful Okada has a tough welcome to the Featherweight division, but possesses notoriously frightening physical power. “Isao” the reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, has been unstoppable in nearly three years. He claimed the interim title by way of disqualification due to a grounded knee at Pancrase 295, and following orbital surgery and recovery, he went on to capture the undisputed King of Pancrase belt from Nazareno Malagarie at Pancrase 305 in May 2019. Known to fans simply as “Akira”, he is widely feared as one of the hardest hitting Pancrase Lightweights, and steps away from his 5th ranked spot in the bracket to face Kobayashi. The 33-year-old has faced some of the best from around the world, and will thrive under the pressure of this bout. A change in weight class could be the test he needs right now. The co-main event sees Emiko Raika collide with Takayo Hashi in what promises to be a test of skills and experience, mixed with sheer will-to-win guts and determination. -

AIBA Women's World Boxing Championships 2019

AIBA Women's World Boxing Championships 2019 Entry List by NOC As of WED 2 OCT 2019 Date of Height NOC Name Gender Weight Category Qualified Birth m / ft in ALB - Albania SELAJ Elsidita W Women 69-75kg Total: 1 ALG - Algeria MANSOURI Fatiha W Women 45-48kg 23 MAR 1997 ROUMAYSA BOUALAM W Women 48-51kg SFOUH OUIDAD W Women 51-54kg 8 MAR 1995 KHELIF HADJILA W Women 54-57kg KHELIF Imane W Women 57-60kg 2 MAY 1999 SELMOUNI Chahira W Women 60-64kg 25 MAR 1997 Total: 6 ARG - Argentina SANCHEZ Leonela W Women 54-57kg 28 MAR 1994 SANCHEZ Dayana Erika Iohanna W Women 57-60kg 28 AUG 1992 PEREZ Lucia Noelia W Women 64-69kg 7 AUG 1992 Total: 3 ARM - Armenia GRIGORYAN Anush W Women 48-51kg AROYAN Anahit W Women 51-54kg HOVSEPYAN Ani W Women 64-69kg 19 MAR 1998 Total: 3 AUS - Australia RILEY Kaila W Women 45-48kg 3 OCT 1986 ROBERTSON Taylah W Women 48-51kg 23 APR 1998 KONSTANTOPOULOU Antonia W Women 51-54kg 11 SEP 1993 NICOLSON Skye Brittany W Women 54-57kg 27 AUG 1995 STRIDSMAN Anja W Women 57-60kg 6 APR 1987 MESSINA Jessica W Women 60-64kg 16 APR 1992 SCOTT Kaye Frances W Women 64-69kg 20 JUN 1984 PARKER Caitlin Anne W Women 69-75kg 17 APR 1996 BAGLEY JESSICA PAIGE W Women 75-81kg 27 FEB 1992 Total: 9 BAR - Barbados GITTENS Kimberly W Women 64-69kg 5 FEB 1992 Total: 1 BDI - Burundi HAVYARIMANA Ornella W Women 48-51kg 1 SEP 1994 Total: 1 BLR - Belarus LUSHCHYK Volha W Women 48-51kg 8 OCT 1984 APANASOVICH YULIYA W Women 51-54kg 10 NOV 1996 BRUYEVICH Helina W Women 54-57kg 20 JUL 1989 YARSHEVICH Ala W Women 57-60kg 20 DEC 1988 KEBIKAVA Victoriya W Women 69-75kg 1 SEP 1985 KAVALEVA Katsiaryna W Women +81kg 17 FEB 1991 Total: 6 BOT - Botswana MODUKANELE Lethabo Bokamoso W Women 45-48kg 25 AUG 1996 KENOSI Keamogetse S. -

The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport

Journal of Sport Management, 2017, 31, 533-545 https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0333 © 2017 Human Kinetics, Inc. ARTICLE The Effects of Sexualized and Violent Presentations of Women in Combat Sport T. Christopher Greenwell University of Louisville Jason M. Simmons University of Cincinnati Meg Hancock and Megan Shreffler University of Louisville Dustin Thorn Xavier University This study utilizes an experimental design to investigate how different presentations (sexualized, neutral, and combat) of female athletes competing in a combat sport such as mixed martial arts, a sport defying traditional gender norms, affect consumers’ attitudes toward the advertising, event, and athlete brand. When the female athlete in the advertisement was in a sexualized presentation, male subjects reported higher attitudes toward the advertisement and the event than the female subjects. Female respondents preferred neutral presentations significantly more than the male respondents. On the one hand, both male and female respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was more attractive and charming than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and more personable than the fighter in the combat ads. On the other hand, respondents felt the fighter in the sexualized ad was less talented, less successful, and less tough than the fighter in the neutral or combat ads and less wholesome than the fighter in the neutral ad. Keywords: brand, consumer attitude, sports advertising, women’s sports February 23, 2013, was a historic date for women’s The UFC is not the only MMA organization featur- mixed martial arts (MMA). For the first time in history, ing female fighters. Invicta Fighting Championships (an two female fighters not only competed in an Ultimate all-female MMA organization) and Bellator MMA reg- Fighting Championship (UFC) event, Ronda Rousey and ularly include female bouts on their fight cards. -

A World Title Shot Is on the Line As Robbie Lawler Battles Matt Brown July 26 in San Jose

A WORLD TITLE SHOT IS ON THE LINE AS ROBBIE LAWLER BATTLES MATT BROWN JULY 26 IN SAN JOSE Las Vegas, Nevada – UFC® returns to SAP Center at San Jose with a title elimination match pitting two knockout artists against one another as No. 1-ranked Robbie Lawler will take on No. 5-ranked Matt Brown with the winner earning a shot at champion Johny Hendricks. Additionally, the card will feature several Bay Area-based fighters in Josh Thomson, Noad Lahat and Kyle Kingsbury. Coming off an impressive third-round finish over an always game Jake Ellenberger, Lawler (23-10, 1 NC, fighting out of Coconut Creek, Fla.) will take on the surging Brown (21-11, fighting out of Columbus, Ohio) in hopes of securing a second crack at UFC gold. Brown, who has put together one of the most impressive runs in mixed martial arts today, currently rides a seven-fight win streak, and will be looking to lock down a title shot he feels is long overdue. On July 26 at SAP Center, two of the best welterweights in the world will put it all on the line in a battle for the top contender position. In addition, light heavyweight (No. 5) Anthony Johnson (17-4, fighting out of Boca Raton, Fla.) is back in the Octagon® after an impressive decision victory over Phil Davis in his return to the UFC earlier this year. The hard-hitting “Rumble” will take on Brazilian star Antonio Rogerio Nogueira (21-5, fighting out of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) as he primes himself for title contention. -

2015 Topps UFC Chronicles Checklist

BASE FIGHTER CARDS 1 Royce Gracie 2 Gracie vs Jimmerson 3 Dan Severn 4 Royce Gracie 5 Don Frye 6 Vitor Belfort 7 Dan Henderson 8 Matt Hughes 9 Andrei Arlovski 10 Jens Pulver 11 BJ Penn 12 Robbie Lawler 13 Rich Franklin 14 Nick Diaz 15 Georges St-Pierre 16 Patrick Côté 17 The Ultimate Fighter 1 18 Forrest Griffin 19 Forrest Griffin 20 Stephan Bonnar 21 Rich Franklin 22 Diego Sanchez 23 Hughes vs Trigg II 24 Nate Marquardt 25 Thiago Alves 26 Chael Sonnen 27 Keith Jardine 28 Rashad Evans 29 Rashad Evans 30 Joe Stevenson 31 Ludwig vs Goulet 32 Michael Bisping 33 Michael Bisping 34 Arianny Celeste 35 Anderson Silva 36 Martin Kampmann 37 Joe Lauzon 38 Clay Guida 39 Thales Leites 40 Mirko Cro Cop 41 Rampage Jackson 42 Frankie Edgar 43 Lyoto Machida 44 Roan Carneiro 45 St-Pierre vs Serra 46 Fabricio Werdum 47 Dennis Siver 48 Anthony Johnson 49 Cole Miller 50 Nate Diaz 51 Gray Maynard 52 Nate Diaz 53 Gray Maynard 54 Minotauro Nogueira 55 Rampage vs Henderson 56 Maurício Shogun Rua 57 Demian Maia 58 Bisping vs Evans 59 Ben Saunders 60 Soa Palelei 61 Tim Boetsch 62 Silva vs Henderson 63 Cain Velasquez 64 Shane Carwin 65 Matt Brown 66 CB Dollaway 67 Amir Sadollah 68 CB Dollaway 69 Dan Miller 70 Fitch vs Larson 71 Jim Miller 72 Baron vs Miller 73 Junior Dos Santos 74 Rafael dos Anjos 75 Ryan Bader 76 Tom Lawlor 77 Efrain Escudero 78 Ryan Bader 79 Mark Muñoz 80 Carlos Condit 81 Brian Stann 82 TJ Grant 83 Ross Pearson 84 Ross Pearson 85 Johny Hendricks 86 Todd Duffee 87 Jake Ellenberger 88 John Howard 89 Nik Lentz 90 Ben Rothwell 91 Alexander Gustafsson -

Engaging Women and Girls In

ENGAGING WOMEN AND GIRLS IN MMA GENERAL AWARENESS COVERING THEORETICAL ISSUES, IMPLICATIONS AND PRACTICE TO ENGAGING WOMEN AND GIRLS AT THE GRASS ROOTS LEVEL OF MIXED MARTIAL ARTS Jorden Curran, November 2020 AWARENESS TOWARDS ENGAGING WOMEN AND GIRLS IN MMA Publication date: November 2020 This information (not including logos or images) may be used free of charge. This document is available for download at www.immaf.org. Enquires regarding this document can be sent to [email protected] and/or [email protected]. The purpose of the document is to offer direction and awareness for members of the International Mixed Martial Arts Federation (IMMAF), towards theoretical issues, barriers and practice of engaging women and girls in the sport of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA). INTRODUCTION Since its launch in 2020, the IMMAF Women’s Commission, led by Hayzia Bellem, has assisted IMMAF member nations in the creation of National Women’s Commissions, worldwide. The aim of the IMMAF Women’s Commission is to give guidance to every country in auditing the situation locally and to define what actions to take to develop MMA for women and girls at every level. At its upper professional level, the sport Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) is a world leader in its representation of gender equality. Pioneering stars of past and present such as Gina Carano, Ronda Rousey, Holly Holm, Cristiane Justino, Amanda Nunes, Valentina Schevchenko, Joanna Jędrzejczyk, Weili Zhang and Rose Namajunas have proved that unlike many of the world’s most prominent sports, women in MMA are able to achieve equal prominence and opportunity in line with that of their male counterparts. -

Jasmina and Frida

Lund University International Marketing and Brand Management Master Thesis June 2021 Distancing From Dirt A Qualitative Study on How Cancel Culture Has Become a Resource for Identity Construction in an Online Setting By: Jasmina Smajlovic & Frida Åhl Supervisor: Jon Bertilsson Examiner: Fleura Bardhi Abstract Title: Distancing From Dirt: A Qualitative Study on How Cancel Culture Has Become a Resource for Identity Construction in an Online Setting Course: BUSN39: Degree Project in Global Marketing Authors: Jasmina Smajlovic & Frida Åhl Supervisor: Jon Bertilsson Examiner: Fleura Bardhi Keywords: Identity Construction, Consumer Identity, Framing, Cancel Culture, Oatly, DisneyPlus Thesis Purpose: With this research we aim to understand the dynamics of consumers' use of cancel culture as a resource for their identity construction online. Theoretical Framework: Theories included were surrounding framing, morality, consumers as moral protagonists, purity and dirt as well as distaste and symbolic violence. These theories were selected to aid with the analysis of the empirical material and to add new insight to the concept of identity construction by negatively distancing from brands. Methodology: This study was conducted with a foundation of a relativist and social constructivist worldview. The research design used is qualitative and the netnography was conducted with an inductive approach. For the analysis, the method of content analysis was used to unfold underlying codes and patterns in the empirical material. Main Findings: This research found that consumers use cancel culture as a resource for identity construction in an online setting. By analysing the empirical material it was found that the constant use of viscous, satirical, emotional and political framing is a way for consumers to negatively distance themselves from brands and other consumers in order to build on their identities. -

Come out Swinging

COME OUT SWINGING COME OUT SWINGING: THE CHANGING WORLD OF BOXING IN GLEASon’S GYM Lucia Trimbur PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2013 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu Cover photo by Issei Nakaya All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Trimbur, Lucia, 1975– Come out swinging : the changing world of boxing in Gleason’s gym / Lucia Trimbur. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15029-1 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Boxing—New York (State) —New York— History. 2. Gymnasiums—New York (State)—New York—History. 3. Athletic clubs—New York (State) —New York—History. 4. Boxers (Sports) —New York (State) —New York— History. 5. Brooklyn (New York, N.Y.) —History. 6. Brooklyn (New York, N.Y.) —Social life and customs. I. Title. GV1125.T75 2013 796.8309747—dc23 2012049335 British Library Cataloging- in- Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std Printed on acid- free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 “Boxing is a Combat, depending more on Strength than the Sword: But Art will yet bear down the Beam against it. A less Degree of Art will tell more than a considerably greater Strength. Strength is cer- tainly what the Boxer ought to fet [sic] out with, but without Art he will succeed but poorly.