10 January 2006 and Boof, Mumbles, Sloon, Humptydoo, Tickets, Walt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON the TAKE T O N Y J O E L a N D M at H E W T U R N E R

Scandals in sport AN ACCOMPANIMENT TO ON THE TAKE TONY JOEL AND MATHEW TURNER Contemporary Histories Research Group, Deakin University February 2020 he events that enveloped the Victorian Football League (VFL) generally and the Carlton Football Club especially in September 1910 were not unprecedented. Gambling was entrenched in TMelbourne’s sporting landscape and rumours about footballers “playing dead” to fix the results of certain matches had swirled around the city’s ovals, pubs, and back streets for decades. On occasion, firmer allegations had even forced authorities into conducting formal inquiries. The Carlton bribery scandal, then, was not the first or only time when footballers were interrogated by officials from either their club or governing body over corruption charges. It was the most sensational case, however, and not only because of the guilty verdicts and harsh punishments handed down. As our new book On The Take reveals in intricate detail, it was a particularly controversial episode due to such a prominent figure as Carlton’s triple premiership hero Alex “Bongo” Lang being implicated as the scandal’s chief protagonist. Indeed, there is something captivating about scandals involving professional athletes and our fascination is only amplified when champions are embroiled, and long bans are sanctioned. As a by-product of modernity’s cult of celebrity, it is not uncommon for high-profile sportspeople to find themselves exposed by unlawful, immoral, or simply ill-advised behaviour whether it be directly related to their sporting performances or instead concerning their personal lives. Most cases can be categorised as somehow relating to either sex, illegal or criminal activity, violence, various forms of cheating (with drugs/doping so prevalent it can be considered a separate category), prohibited gambling and match-fixing. -

Charles Kelleway Passed Away on 16 November 1944 in Lindfield, Sydney

Charle s Kelleway (188 6 - 1944) Australia n Cricketer (1910/11 - 1928/29) NS W Cricketer (1907/0 8 - 1928/29) • Born in Lismore on 25 April 1886. • Right-hand bat and right-arm fast-medium bowler. • North Coastal Cricket Zone’s first Australian capped player. He played 26 test matches, and 132 first class matches. • He was the original captain of the AIF team that played matches in England after the end of World War I. • In 26 tests he scored 1422 runs at 37.42 with three centuries and six half-centuries, and he took 52 wickets at 32.36 with a best of 5-33. • He was the first of just four Australians to score a century (114) and take five wickets in an innings (5/33) in the same test. He did this against South Africa in the Triangular Test series in England in 1912. Only Jack Gregory, Keith Miller and Richie Benaud have duplicated his feat for Australia. • He is the only player to play test cricket with both Victor Trumper and Don Bradman. • In 132 first-class matches he scored 6389 runs at 35.10 with 15 centuries and 28 half-centuries. With the ball, he took 339 wickets at 26.33 with 10 five wicket performances. Amazingly, he bowled almost half (164) of these. He bowled more than half (111) of his victims for New South Wales. • In 57 first-class matches for New South Wales he scored 3031 runs at 37.88 with 10 centuries and 11 half-centuries. He took 215 wickets at 23.90 with seven five-wicket performances, three of these being seven wicket hauls, with a best of 7-39. -

Business Justice Ministry Cosimo Ferri, a Number of Entific, Cultural and Artistic Activities Aiming Together

SUBSCRIPTION SUNDAY, OCTOBER 4, 2015 THULHIJJA 20, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Interior Ministry MoE official UAE goes to Aguero hits buys four discusses fees, polls with some five as Man Airbus civilian visas, teachers at citizens still City rout helicopters3 private4 schools denied13 vote Newcastle20 Kuwaitis driving vehicles Min 26º Max 43º with Gulf plates warned High Tide 03:20 & 14:35 Low Tide Violators given one month to make change 10:35 & 22:25 40 PAGES NO: 16657 150 FILS KUWAIT: All Kuwaiti motorists who own and drive cars with license plates from Gulf countries have one month First Iran hajj dead flown home during which they must turn in these license plates to be replaced by Kuwaiti ones, said a Ministry of Interior TEHRAN: The first bodies of Iranians killed in a stam- official yesterday. Some Kuwaiti motorists drive cars pede at the hajj arrived home from Saudi Arabia yester- with license plates from Gulf countries and use them to day after a controversial nine-day delay and questions break serious traffic rules, thinking erroneously that the over the final death toll. President Hassan Rouhani and arm of the law will not reach them because they are other top officials laid white flowers on coffins ata driving cars with foreign license plates, said the min- somber ceremony in Tehran for the 104 pilgrims - istry’s assistant undersecretary for traffic affairs Maj Gen among 464 Iranians declared dead in the Sept 24 Abdullah Al-Muhanna in a press statement. crush. Iran has accused Saudi Arabia of incompetence He said some of the traffic infractions these motorists in its handling of safety at the hajj, further souring rela- commit are very serious, such as running red lights and tions already strained by the civil war in Syria and con- driving at outrageous speeds. -

Issue 43: Summer 2010/11

Journal of the Melbourne CriCket Club library issue 43, suMMer 2010/2011 Cro∫se: f. A Cro∫ier, or Bi∫hops ∫taffe; also, a croo~ed ∫taffe wherewith boyes play at cricket. This Issue: Celebrating the 400th anniversary of our oldest item, Ashes to Ashes, Some notes on the Long Room, and Mollydookers in Australian Test Cricket Library News “How do you celebrate a Quadricentennial?” With an exhibition celebrating four centuries of cricket in print The new MCC Library visits MCC Library A range of articles in this edition of The Yorker complement • The famous Ashes obituaries published in Cricket, a weekly cataloguing From December 6, 2010 to February 4, 2010, staff in the MCC the new exhibition commemorating the 400th anniversary of record of the game , and Sporting Times in 1882 and the team has swung Library will be hosting a colleague from our reciprocal club the publication of the oldest book in the MCC Library, Randle verse pasted on to the Darnley Ashes Urn printed in into action. in London, Neil Robinson, research officer at the Marylebone Cotgrave’s Dictionarie of the French and English tongues, published Melbourne Punch in 1883. in London in 1611, the same year as the King James Bible and the This year Cricket Club’s Arts and Library Department. This visit will • The large paper edition of W.G. Grace’s book that he premiere of Shakespeare’s last solo play, The Tempest. has seen a be an important opportunity for both Neil’s professional presented to the Melbourne Cricket Club during his tour in commitment development, as he observes the weekday and event day The Dictionarie is a scarce book, but not especially rare. -

Cricket Memorabilia Society Postal Auction Closing at Noon 10

CRICKET MEMORABILIA SOCIETY POSTAL AUCTION CLOSING AT NOON 10th JULY 2020 Conditions of Postal Sale The CMS reserves the right to refuse items which are damaged or unsuitable, or we have doubts about authenticity. Reserves can be placed on lots but must be agreed with the CMS. They should reflect realistic values/expectations and not be the “highest price” expected. The CMS will take 7% of the price realised, the vendor 93% which will normally be paid no later than 6 weeks after the auction. The CMS will undertake to advertise the memorabilia for auction on its website no later than 3 weeks prior to the closing date of the auction. Bids will only be accepted from CMS members. Postal bids must be in writing or e-mail by the closing date and time shown above. Generally, no item will be sold below 10% of the lower estimate without reference to the vendor.. Thus, an item with a £10-15 estimate can be sold for £9, but not £8, without approval. The incremental scale for the acceptance of bids is as follows: £2 increments up to £20, then £20/22/25/28/30 up to £50, then £5 increments to £100 and £10 increments above that. So, if there are two postal bids at £25 and £30, the item will go to the higher bidder at £28. Should there be two identical bids, the first received will win. Bids submitted between increments will be accepted, thus a £52 bid will not be rounded either up or down. Items will be sent to successful postal bidders the week after the auction and will be sent by the cheapest rate commensurate with the value and size of the item. -

Lancashire Red & White Stripes

RUGBY FOOTBALL UNION TOSHIBA COUNTY CHAMPIONSHIP LANCASHIRE RED & WHITE STRIPES VERSUS CHESHIRE BLUE & WHITE STRIPES LIVERPOOL. ST. HELENS F.C. TUESDAY 25th OCTOBER 1988 Kick Off 7-15 p.m. PROGRAMME 30p Méet theVAUXHALL, OPEL XV 15. BELMONT SRi Safe Handling - Vivid Acceleration under a ny Con· ditions. 14. A STRA GTE 16V 2.0i A Neweomer 10 the Team - an Absolutc Flye r. 13. CAVALIER SRi 130 Sporty Injecti on of Front End Power 10 Out pace the Opposition. 12. CAVALIER GL Not as Fast Off the Mark but makes Laughing Stock of most Opp"nents. II. CARLTON Time proven qualities with 1nternalÎonal Distin ction! 10. NOVA SR Stand Omsh - but now holding a Firm Grasp on the Pole Position. 9. NOV A GTE 1.6i Peter Pan qualities herc - Exce ptiona ll y Quick 00- the Mark with Great Pa ss În g Potentia l. 1. CAVALIER D IESEL Powerfu l \Vith Economy of MovCl11cnl - Plcl1t y of Torque tao! 2. NOVA DlAMOND Sparkling Reliability - Neve r out or Ist Fifteen . 3. ASTRA DIESEL Laads of Power Lüw Dowil whcre il'S needed. 4. ASTRA ESTA TE Solid W orkhorse - Makcs lots of Space to \Yo rk in. 5. CA RLTON ESTATE Biggest Member of the Tcam. Makes a ny Work load look easy. o. MANTA COUPE Gutsy Performer, Great T ra ck Record. 7. MANTA GTE HATCH Meaner looking, Fa stcr and ctTe rs more Openings. 8. SENATOR CD 3.0i Smooth, Stylish long legged Performer. SEE TH E REST OF THE LlNE UP AT: FA RNW ORTH GA RAGE Derby Raad, Widnes Tel. -

History of Lee Lacrosse Club

LEE LACROSSE CLUB Lee Lacrosse Club I. A brief history of Lee Lacrosse Club ..................................................................... 3 II. Roll of honour ........................................................................................................ 8 A. Lee second team (Lee A) ................................................................................... 8 B. Lee third team (LeeB) ........................................................................................ 8 C. Lee Juniors ......................................................................................................... 8 D. Representative honours ...................................................................................... 9 1. England .......................................................................................................... 9 2. South of England v North of England ............................................................ 9 3. In squad (of 19) that played Dennison University on 08/01/72 ................... 10 4. In squad (of 19) that played Australia on 06/05/72 ..................................... 10 5. In squad (of 20) that played Canada on ??/??/78 ........................................ 10 6. Possible South of England representative records ....................................... 11 7. North v South (Juniors) - 1962 .................................................................... 11 8. Cup competitions ......................................................................................... 11 III. League -

Cricket, Football & Sporting Memorabilia 5Th, 6Th and 7Th March

knights Cricket, Football & Sporting Memorabilia 5th, 6th and 7th March 2021 Online live auction Friday 5th March 10.30am Cricket Memorabilia Saturday 6th March 10.30am Cricket Photographs, Scorecards, Wisdens and Cricket Books Sunday 7th March 10.30am Football & Sporting Memorabilia Next auction 10th & 11th July 2021 Entries invited A buyer’s premium of 20% (plus VAT at 20%) of the hammer price is Online bidding payable by the buyers of all lots. Knights Sporting Limited are delighted to offer an online bidding facility. Cheques to be made payable to “Knight’s Sporting Limited”. Bid on lots and buy online from anywhere in the world at the click of a Credit cards and debit accepted. mouse with the-saleroom.com’s Live Auction service. For full terms and conditions see overleaf. Full details of this service can be found at www.the-saleroom.com. Commission bids are welcomed and should be sent to: Knight’s Sporting Ltd, Cuckoo Cottage, Town Green, Alby, In completing the bidder registration on www.the-saleroom.com and Norwich NR11 7PR providing your credit card details and unless alternative arrangements Office: 01263 768488 are agreed with Knights Sporting Limited you authorise Knights Mobile: 07885 515333 Sporting Limited, if they so wish, to charge the credit card given in part Email bids to [email protected] or full payment, including all fees, for items successfully purchased in the auction via the-saleroom.com, and confirm that you are authorised Please note: All commission bids to be received no later than 6pm to provide these credit card details to Knights Sporting Limited through on the day prior to the auction of the lots you are bidding on. -

2020 Yearbook

-2020- CONTENTS 03. 12. Chair’s Message 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 2 & Tier 3 04. 13. 2020 Inductees Vale 06. 14. 2020 Legend of Australian Sport Sport Australia Hall of Fame Legends 08. 15. The Don Award 2020 Sport Australia Hall of Fame Members 10. 16. 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 1 Partner & Sponsors 04. 06. 08. 10. Picture credits: ASBK, Delly Carr/Swimming Australia, European Judo Union, FIBA, Getty Images, Golf Australia, Jon Hewson, Jordan Riddle Photography, Rugby Australia, OIS, OWIA Hocking, Rowing Australia, Sean Harlen, Sean McParland, SportsPics CHAIR’S MESSAGE 2020 has been a year like no other. of Australian Sport. Again, we pivoted and The bushfires and COVID-19 have been major delivered a virtual event. disrupters and I’m proud of the way our team has been able to adapt to new and challenging Our Scholarship & Mentoring Program has working conditions. expanded from five to 32 Scholarships. Six Tier 1 recipients have been aligned with a Most impressive was their ability to transition Member as their Mentor and I recognise these our Induction and Awards Program to prime inspirational partnerships. Ten Tier 2 recipients time, free-to-air television. The 2020 SAHOF and 16 Tier 3 recipients make this program one Program aired nationally on 7mate reaching of the finest in the land. over 136,000 viewers. Although we could not celebrate in person, the Seven Network The Melbourne Cricket Club is to be assembled a treasure trove of Australian congratulated on the award-winning Australian sporting greatness. Sports Museum. Our new SAHOF exhibition is outstanding and I encourage all Members and There is no greater roll call of Australian sport Australian sports fans to make sure they visit stars than the Sport Australia Hall of Fame. -

Roger Page Cricket Books

ROGER PAGE DEALER IN NEW AND SECOND-HAND CRICKET BOOKS 10 EKARI COURT, YALLAMBIE, VICTORIA, 3085 TELEPHONE: (03) 9435 6332 FAX: (03) 9432 2050 EMAIL: [email protected] ABN 95 007 799 336 OCTOBER 2016 CATALOGUE Unless otherwise stated, all books in good condition & bound in cloth boards. Books once sold cannot be returned or exchanged. G.S.T. of 10% to be added to all listed prices for purchases within Australia. Postage is charged on all orders. For parcels l - 2kgs. in weight, the following rates apply: within Victoria $14:00; to New South Wales & South Australia $16.00; to the Brisbane metropolitan area and to Tasmania $18.00; to other parts of Queensland $22; to Western Australia & the Northern Territory $24.00; to New Zealand $40; and to other overseas countries $50.00. Overseas remittances - bank drafts in Australian currency - should be made payable at the Commonwealth Bank, Greensborough, Victoria, 3088. Mastercard and Visa accepted. This List is a selection of current stock. Enquiries for other items are welcome. Cricket books and collections purchased. A. ANNUALS AND PERIODICALS $ ¢ 1. A.C.S International Cricket Year Books: a. 1986 (lst edition) to 1995 inc. 20.00 ea b. 2014, 2015, 2016 70.00 ea 2. Athletic News Cricket Annuals: a. 1900, 1903 (fair condition), 1913, 1914, 1919 50.00 ea b. 1922 to 1929 inc. 30.00 ea c. 1930 to 1939 inc. 25.00 ea 3. Australian Cricket Digest (ed) Lawrie Colliver: a. 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15, 25.00 ea. b. 2015-2016 30.00 ea 4. -

Justice Qayyum's Report

PART I BACKGROUND TO INQUIRY 1. Cricket has always put itself forth as a gentleman’s game. However, this aspect of the game has come under strain time and again, sadly with increasing regularity. From BodyLine to Trevor Chappel bowling under-arm, from sledging to ball tampering, instances of gamesmanship have been on the rise. Instances of sportsmanship like Courtney Walsh refusing to run out a Pakistani batsman for backing up too soon in a crucial match of the 1987 World Cup; Imran Khan, as Captain calling back his counterpart Kris Srikanth to bat again after the latter was annoyed with the decision of the umpire; batsmen like Majid Khan walking if they knew they were out; are becoming rarer yet. Now, with the massive influx of money and sheer increase in number of matches played, cricket has become big business. Now like other sports before it (Baseball (the Chicago ‘Black-Sox’ against the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series), Football (allegations against Bruce Grobelar; lights going out at the Valley, home of Charlton Football club)) Cricket Inquiry Report Page 1 Cricket faces the threat of match-fixing, the most serious threat the game has faced in its life. 2. Match-fixing is an international threat. It is quite possibly an international reality too. Donald Topley, a former county cricketer, wrote in the Sunday Mirror in 1994 that in a county match between Essex and Lancashire in 1991 Season, both the teams were heavily paid to fix the match. Time and again, former and present cricketers (e.g. Manoj Prabhakar going into pre-mature retirement and alleging match-fixing against the Indian team; the Indian Team refusing to play against Pakistan at Sharjah after their loss in the Wills Trophy 1991 claiming matches there were fixed) accused different teams of match-fixing. -

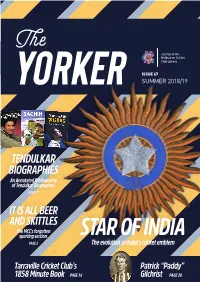

TENDULKAR BIOGRAPHIES an Annotated Bibliography of Tendulkar Biographies

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library ISSUE 67 SUMMER 2018/19 TENDULKAR BIOGRAPHIES An Annotated Bibliography of Tendulkar Biographies. PAGE 11 IT IS ALL BEER AND SKITTLES The MCC's forgotten sporting section. STAR OF INDIA PAGE 3 The evolution as India’s cricket emblem Tarraville Cricket Club’s Patrick “Paddy” 1858 Minute Book PAGE 14 Gilchrist PAGE 20 ISSN 1839-3608 PUBLISHED BY THE MELBOURNE CRICKET CLUB CONTENTS: © THE AUTHORS AND THE MCC The Yorker is edited by Trevor Ruddell with the assistance of David Studham. It’s all Beer and Life in the MCC Graphic design and publication by 3 Skittles 16 Library George Petrou Design. Thanks to Jacob Afif, James Brear, Lynda Carroll, Edward Cohen, Gaye Fitzpatrick, Stephen Flemming, Helen Hill, James Howard, The Star of India Patrick “Paddy” Quentin Miller, Regan Mills, George Petrou, Trevor Ruddell, Ann Rusden, Andrew Lambert, 8 20 Gilchrist Michael Roberts, Lesley Smith, David Studham, Stephen Tully, Andrew Young, and our advertiser Roger Pager Cricket Books. Tendulkar The views expressed are those of the 11 Biographies A Nation’s Undying editors and authors, and are not those of the Melbourne Cricket Club. All reasonable 26 Love for the Game attempts have been made to clear copyright before publication. The publication of an advertisement does not Tarraville Cricket imply the approval of the publishers or the MCC 14 Club’s 1858 Minute Book Reviews for goods and services offered. Published three times a year, the Summer Book 28 issue traditionally has a cricket feature, the Autumn issue has a leading article on football, while the Spring issue is multi-sport focused.