Teaching the Relationship Between Business and Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lexet Jan-June 2017

SYMBIOSIS LAW SCHOOL, PUNE FROM THE EDITORIAL DESK Care | Courage | Competence | Collaboration The stoic ght put up by Muslim (Constituent of Symbiosis International University ) women against the sexist practices Re-accredited by NAAC with 'A' Grade that plague their lives has once more highlighted the glaring lacuna in the Indian legal system; a Uniform Civil Code. But they are not the rst ghting for this cause and neither will they be the last. S Y M B I O S I S India is home to different religions, castes, communities and tribes, each January-June 2017 Volume 17 - Issue 2 of which follows their own set of personal laws, varying in their Congratulations! SLS, Pune won the runners up trophy in the National Rounds sources, philosophy and application. for Philip C. Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition, 2017 This constraint was observed by the and qualied for the World Rounds. Constituent Assembly who in their wisdom inserted Article 44 in the Constitution; a Directive Principle of State Policy to establish a Uniform Civil Code for India. A U n i f o r m C i v i l C o d e w o u l d essentially be a counterpart to the criminal code, administering the same set of secular civil laws equally to all Indians, giving the same respect deserved, something personal laws h a v e f a i l e d t o a c h i e v e . T h e u n d e r l y i n g p r i n c i p l e i s t h a t constitutional law will override religious law in a secular republic. -

Symbiosis International (Deemed University) 002 Content • a Foreign Affair That Founded Symbiosis

Symbiosis International (Deemed University) 002 Content • A Foreign Affair that Founded Symbiosis ................................................................................................................................................................. • Chancellor’s Message ................................................................................................................................................................................................... • Pro Chancellor’s Message ........................................................................................................................................................................................... • Vice Chancellor’s Message ........................................................................................................................................................................................... • Symbiosis Family ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ • Authorities ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Symbiosis Managing Committee ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Download This PDF File

Is the Welfare State in Crisis? Debating the condition of the welfare state in India Contents Editorial Whither Welfare State? Kannamma Raman 5 Articles Privatising Education in India and the Withdrawing Welfare State 19 Anuya Warty The Co-existence of Widespread Hunger and the Right to Food Impact of the 32 Withdrawal of the Welfare State on Malnutrition Among Children in Karnataka Darshana Mitra, Mohammed Afeef, Vinay Sreenivasa, Narasimhappa TV Urban Informality: Symptomatic of an end of the Welfare State? 49 Akriti Bhatia Planning for Welfare in Post-Liberalisation India: The Challenges of 62 Building Human Capital Saumya Tewari Fixed Dose Combinations and their Ban: Issues of Concern 72 S. Srinivasan Geographical Indications and Farmers’ Welfare: Role of State in 90 Strengthening Governance N. Lalitha, Soumya Vinayan Re-examining the Delivery of Legal Aid in Mumbai 108 Vandita Morarka Commentaries The Welfare State – Challenges for Governance in India 127 Venkatesan Ramani Foundations of an Effective Self-Help System 140 Parth Shah Behavioural Re-design of Subsidies 150 V. Kumaraswamy The Benevolence of MGR, Subaltern Audiences and the Tamil Nadu State 166 Gopalan Ravindran Maternity Benefit Legislation: Reinforcing Patriarchy, Excluding Intersectionality 177 and Ignoring Impact Kirthi Jayakumar Book Review When Crime Pays: Money and Muscle in Indian Politics 181 Ashwin Parthasarathy Women and Disaster in South Asia– Survival, Security and Development 186 Drashti Thakkar 1 Editor Managing Editor Kannamma Raman Padma Prakash Political Scientist Editor, eSocialSciences Retired Professor, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Assistant Editors Ashwin Parthasarathy Research Scholar JPAC is jointly published by Forum for Research on Civic Affairs and eSocialSciences, Mumbai. -

Faculty Profile

gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg Faculty Profile Name: Richa Jain Designation: Assistant Professor Teaching Areas: Competition law Health and Medicine Law Alternative Dispute Resolution Research Interests: Competition law Intellectual Property Rights Health and Medicine Law Alternative Dispute Resolution Education: LLM : Symbiosis International University, Pune BA. LLB: Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University, Delhi UGC NET 2018 Professional Experience (5 Years): 1. 2019 ‐ Present, Assistant Professor, ICFAI law School, IFHE, Hyderabad 2. April 2018‐ June 2019‐ Research Associate Law, Competition Commission of India (CCI), Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India, 3. October 2017‐ May 2019‐ Guest Faculty‐ Faculty of Law, Bharati Vidyapeeth Institute of Management and Research, Delhi (Affiliated to Bharati Vidyapeeth Deemed University, Pune) 4. March 2016‐ June 2017‐ Faculty In‐charge, Centre for Intellectual Property Research and Advocacy, Centre for Specialisation in Performing Arts; Deputy In‐charge Centre for Human Rights, Teaching Assistant‐ Symbiosis Law School, Hyderabad, Symbiosis International University, Pune Selected Publications: 1. Authored book chapter titled ‘Trade Associations: Platform for Industry Interactions or Collusion?’ in Anti‐Competitive Agreements: Competition Law Dynamics, ALT Publications, ISBN: 978‐93‐90255‐00‐9. 2. Editor of book titled ‘Competition Law Sectoral Countours’, ALT Publications, ISBN: 978‐81‐945732‐9‐6 3. Editor of book titled ‘E‐Commerce and Competition’, ALT Publications, ISBN: 978‐81‐945732‐7‐2 4. Editor of book titled ‘Emerging Trends in Intellectual Property Rights’. 5. ‘Bid rigging in public procurement‐ evaluation of evidences in the orders of the Commission’ in Fairplay, published by the Competition Commission of India, 2018. 6. ‘Lesser penalty provisions under Competition Act, 2002’ in Fairplay, published by the Competition Commission of India, 2018. -

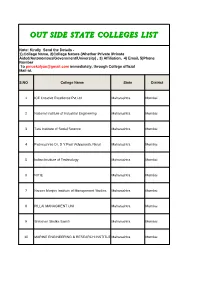

Out Side State Colleges List

OUT SIDE STATE COLLEGES LIST Note: Kindly Send the Details - 1).College Name, 2)College Nature (Whether Private /Private Aided/Autonomous/Government/University) , 3) Affiliation, 4) Email, 5)Phone Number To [email protected] immediately, through College official Mail-id. S.NO College Name State District 1 ICE Creative Excellence Pvt Ltd Maharashtra Mumbai 2 National Institute of Industrial Engineering Maharashtra Mumbai 3 Tata Institute of Social Science Maharashtra Mumbai 4 Padmashree Dr. D Y Patil Vidyapeeth, Nerul Maharashtra Mumbai 5 Indian Institute of Technology Maharashtra Mumbai 6 NITIE Maharashtra Mumbai 7 Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies Maharashtra Mumbai 8 PILLAI MANAGMENT UNI Maharashtra Mumbai 9 Shikshan Shulka Samiti Maharashtra Mumbai 10 MARINE ENGINEERING & RESEARCH INSTITUTEMaharashtra Mumbai 11 Institute of Hotel Management, Catering Technoloty Maharashtra& Applied Nutrition Mumbai 12 Central Institute for Research of Cotton TechnologyMaharashtra Mumbai 13 TATA INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Maharashtra Mumbai 14 Grant Medical College Maharashtra Mumbai 15 College of Social Work Nirmala Niketan Maharashtra Mumbai 16 P.I.I.T,NEW PANVEL,NAVI MUMBAI. Maharashtra Mumbai 17 Ali Yavar Jung National Institute for the Hearing HandicappedMaharashtra Mumbai 18 Sir J.J. group of Hospitals Maharashtra Mumbai 19 St. Xavier s College Mumbai Maharashtra Mumbai 20 Sound Ideaz Academy Maharashtra Mumbai 21 King Edward Memorial Hospital Maharashtra Mumbai 22 Jamnalal Bajaj Institute Maharashtra Mumbai 23 Bombay Flying Club -

(Deemed University) Symbiosis Law School, Pune

SYMBIOSIS INTERNATIONAL (Deemed University) Symbiosis Law School, Pune NAAC 5.3.3. Average Number of Sports and Cultural activities / competitions organized at the institutions level per year File Name: 5.3.3_SLSP_16-17_sportsculturalactivities.pdf Sno Details of Documents No. of Pages 1. Mooting Calendar 1 2. Nani Palkiwala Memorial Competition 12 3. Induction and Commencement Programme, 2 4 5th Annual National Conference on Contemporary 1 Legal Scholarship Cum Workshop 5 Students Advisory Board 1 6 Symptom 1 7 Community Legal Care 1 8 Moot Achievement 2 9 Co Curricular and Extra Curricular Activities 7 10 Symbhav 2 11 Symbiosis International Criminal Moot Court 1 Trial Advocacy (SICTA) 12 Alumni Meet 2 13 Art Workshop and Exhibition 1 14 Community Legal Care 2 15 Co Curricular and Extra Curricular Activities 7 including Moot court and Sports . INDUCTION PROGRAMME 2016: 27th& 28th July, 2016 SLS, P organized Induction Programme 2016 for the students of 1st Year BA/BBA/LLB (Hons.), LLB and LLM. Dr. Gurpur gave an introduction to the college, its curriculum and highlighted the well-rounded education that includes authentic Liberal Arts, Soft Skills and IT courses. Thereafter, the students were introduced to different academic and administrative rules, regulations and processes by Professors and admin staff respectively. Lighting of the lamp by the dignitaries 03 The second day imparted education on Health and Wellness issues, orientation towards career in Civil Services, Company Secretary Course and Waste Management. Our distinguished alumni Mr. Shahshank Ratnoo, Indian Revenue Service, Ms. Henaa Mall Vaidya, Senior Manager, Investment Banking at AK Capital Services Limited, Delhi, Mr. -

Mr. Abhijit D. Vasmatkar, ICCR Chair Professor B.Sc

Mr. Abhijit D. Vasmatkar, ICCR Chair Professor B.Sc. LL.M NET (Double Gold Medalist) [email protected] 9422551503 Current Profile and Areas of Interests Presently working with Symbiosis Law School, Hyderabad, as an Assistant Professor since 17th December, 2014. Worked with Symbiosis Law School, Pune from 2nd July 2007 till 16th December, 2014. Special Achievements Honoured with „Best Overall Performance Award – 2014-15‟ by SLS, Hyderabad on 5th September, 2015. Honoured with a “Reliable Employee Award 2012-13” by SLS Pune on 5th September 2013. Honoured with a “Value conscious, adoptable and commendable contribution Award – 2011-12” by SLS Pune on 5th September 2012. Honoured with a prestigious “ICCR Rotating Chair- 2010-11”, sponsored by Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India for a period of six months to do research on International Trade Laws in the Leibniz University, Hannover, Germany, in 2010. Qualified with University Grants Commissions‟ “National Eligibility Test”, in June 2009. Honoured with Chancellor‟s Gold Medal for standing first in LL.M. examination, conducted by Symbiosis International University, Pune. (Batch 2005-07) Honoured with Adv. Nani Palkhiwala Trust Gold Medal for Academic Excellence, in December, 2007. Research Contribution Presented a research paper in “2nd International Multidisciplinary Law Conference - 2016” titled „Dispute Settlement under ASEAN: An Investigation‟, organized by Symbiosis Law School, Hyderabad in October, 2016. Presented a research paper in “Ist International Multidisciplinary Law Conference - 2015” titled „EU-India Free Trade Agreement: Issues and Concerns‟, organized by Symbiosis Law School, Hyderabad in September, 2015. Published a book „Competition Law and Merger & Acquisitions in Indian Telecom Sector‟, by Lap Lambart, Germany, in December, 2013. -

PUNE Care | Courage | Competence | Collaboration Constituent of Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Lavale, Pune

SYMBIOSIS LAW SCHOOL - PUNE Care | Courage | Competence | Collaboration Constituent of Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Lavale, Pune Three Year LL.B. Programme (Cafeteria Approach with CGPA System) Academic Year 2020-2021 1) Director profile: Dr. (Mrs.) Shashikala Gurpur is a distinguished academician and orator having presented more than 200 invited lectures, workshops and seminars across India, Thailand, US, UK, Ireland, Germany, Australia, Canada and UAE. She has an outstanding career with a wide range of experience in teaching, research and industry and has been continuing with Symbiosis Law School, Pune since 2007. Academic and Research Distinctions: Dr. Gurpur had her formal schooling in Kannada medium in Gurpur, Karnataka. She pursued higher education in science and law from Mangalore University. Dr. Gurpur received her Ph.D. in International Law from Mysore University where she was the topper and Gold medalist in LL.M. Her career span includes long years of experience in legal literacy and gender training, where she served as the Co- Director in gender and human rights-based wing of an NGO for 2 years. She has also worked as HR Manager & Administration in an MNC in Abu Dhabi, UAE from 2004 to 2007. She has more than 24 years of teaching experience which includes tenures in NLSIU, Bangalore, SDM Law College, Mangalore, Manipal Institute of Communication, MAHE, Manipal and University College Cork, Ireland. Her teaching and research interests encompass Jurisprudence, Media Law, International Law and Human Rights, Teaching and Research Methodology, Feminist Legal Studies, Biotechnology Law, Law and Social Transformation besides having guided more than sixty-five Masters and twelve Ph.D. -

SYMBIOSIS INSTITUTE of HEALTH SCIENCES B.Sc. Medical Technology

SYMBIOSIS INSTITUTE OF HEALTH SCIENCES A Constituent of Symbiosis International University (SIU) (Established under Section 3 of the UGC Act, 1956,by notification No.F.9-12/2001-U.3 of the Government of India.) B.Sc. Medical Technology STUDENT HANDBOOK Batch 2017 - 2020 Senapati Bapat Road, Pune 411004, Maharashtra, India Tele No: +91-20-25658012 Ext. 503, 507,508, 512, 527, 528 email : [email protected]; Website :www.sihspune.org INDEX 1. Director’s Message 2. About SIHS 3. Academics 4. Programme Structure 5. Teaching, Learning & Evaluation 6. Learning Resource Centers a) Library b) Computer Lab 7. Results & Convocation 8. Co-curricular Activities 9. Students’ Committees 10. Administration a) Eligibility and Requisite Documents b) Personal details c) Parents / guardians contact details d) Undertakings e) Whom to Contact f) Code of Conduct 11. Facilities a) Hostel b) Mess c) Food court d) Disaster & Emergency evacuation management plan e) Health Care 12. Symbiosis Institutes 13. About Pune City MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR Welcome to the Symbiosis International University (SIU), Symbiosis Institute of Health Sciences (SIHS) and to the programme in B.Sc. (Medical Technology). I take this opportunity on behalf of all of us at SIHS to welcome you to the threshold of an exciting, rewarding and satisfying learning experience. SIHS brings together people from various specialties of the medical, health and allied professions and related sectors. This mix of professionals, which enables you to know your fellow students – both seniors and peers- and use them, as a learning resource is an important part of the training methodology followed. At SIHS, we are committed to ensure that we maintain an institutional culture, which fosters equality and celebrates diversity. -

MIT-WPU School Of

Welcome to School of Law 05 50+ 1,00,000+ 54,000+ 8,500+ Active Universities Institutes owned by Alumni Globally Active Students Total Employees works with Formulated by MAEER MAEER Group Higher Education On Campus MAEER (with 3,000 faculties) Faculty of Law School of Law Bachelor of Law Admission year 2021 Engineering Management Education Commerce Design Diploma We strictly follow COVID-19 Guidelines Art & Media Polytechnic Science Liberal Arts Economics Ph.D. Government Pharmacy Law Peace Sustainability Studies Academic Leadership Dr. Ravikumar M. Chitnis Dr. Milind Pande Dr. Prashant Dave Dr. Shailashree Haridas Pro – Vice Chancellor Pro – Vice Chancellor Registrar Dean Faculty of Governance & Commerce and Economics Dr. Prasad Khandekar Dr. Dnyanesh Limaye Dr. Anuradha Parasar Dr. Srinivas Subbarao Dean Dean Dean Dean Faculty of Engineering & Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy & Faculty of Law, Liberal Arts, Faculty of Polytechnic, Science and Design Sustainability Studies Fine Arts, Media & Journalism Management Non-Academic Leadership Mr. Pravin Patil Mr. Jay Wadhwani Mr. Jimit Dattani Chief Executive Officer, CIAP Chief Accounts and Finance Officer Chief Technology Officer Mr. Sachin Mohadikar Dr. Uday kumar Mr. Rakesh Ranjan Director Marketing Director Admissions Director HR Dr. Pournima Inamdar Head of School Dr. Pournima N. Inamdar is a passionate academician and a zealous lawyer. She completed her Bachelor of Laws (LL.B) in 1998, her Master of Laws (LL.M) in 2004 and her Ph.D. in 2017 from Nagpur University. She is the Head of School at MIT-WPU Faculty of Law. Prior to joining academia, she worked as an Advocate for 4 years before the Bombay High Court (Nagpur Bench). -

SYMBIOSIS LAW SCHOOL, PUNE Care | Courage | Competence | Collaboration One Year LL.M

SYMBIOSIS LAW SCHOOL, PUNE Care | Courage | Competence | Collaboration One Year LL.M. Admission Process & Rules, 2021 LL.M. Programme 2021-2022: Under the Centre for Post-Graduate Legal Studies (CPGLS), SLS- Pune offers a one year LL.M. programme with the following specializations: 1. Specializations: - Business and Corporate Law - Constitutional and Administrative Law - Innovation, Technology and Intellectual Property Law - Criminal and Security Law - Human Rights Law - Law, Policy and Good Governance - Family Law - European Union Legal Studies Note: A specialization will be offered, subject to minimum 5 admissions in the Specialization Group. 2. DURATION : One Year (Full Time) SANCTIONEDINTAKE : 80 Students MEDIUMOFINSTRUCTION : English PATTERN OFPROGRAMME : Semester Pattern: 2 Semesters(Total) 3. ELIGIBILITY: Three or Five Year LL.B. Degree from any Indian or Foreign University recognized by the UGC with at least 50% marks or equivalent grade [45% for SC/ST Candidates]. Candidates who have appeared for the final year LL.B. examination may also apply. 4. ADMISSION PROCESS: Step 1: Apply online For SLS Pune, please visit - www.symlaw.ac.in Step 2: All India Admission Test (AIAT) Online Home Based Proctored Test Admission to LL.M (One Year) is offered through Symbiosis All India Admission Test (AIAT) Online Home Proctored Test, which consists of: 4.1 AIAT (Online Home Proctored Test): This comprises of objective and subjective written tests to assess the teaching aptitude, research aptitude, legal aptitude and basic legal knowledge. It includes questions from the following areas: Research Methodology, Legal Reasoning, Legal Aptitude, Jurisprudence, Constitutional Law, IPC, Public International Law, Human Rights, Corporate Law (Contract Act, Companies Act, etc.), Family Law and Environmental Law- Weightage 70%. -

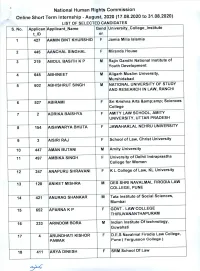

August, 2020 (17.08.2020 to 31.08.2020) S

National Human Rights Commission Online Short Term Internship - August, 2020 (17.08.2020 to 31.08.2020) s. No. i^pplican ftpplicant_Name Gend Jniversity_CollegeJnstitute tJD er 1 427 AAWIIN BINT KHURSHID F Jamia Milia Islamia 2 445 AANCHAL SINGHAL F Vliranda House 3 219 ABDUL BASITH KP M Rajiv Gandhi National Institute of Youth Development 4 645 ABHiNEET M Aligarh Muslim University, Murshidabad 5 602 ABHISHRUT SINGH M NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF STUDY AND RESEARCH IN LAW, RANCHI 6 527 ABIRAMI F Sri Krishna Arts & Sciences College 7 2 ADRIKA BAISHYA F AMITY LAW SCHOOL, AMITY UNIVERSITY, UTTAR PRADESH 8 154 AISHWARYA BHUTA F JAWAHARLAL NEHRU UNIVERSITY 9 3 AISIRI RAJ F School of Law. Christ University 10 447 AWIAN BUTANl M Amity University 11 497 AMBIKA SINGH F University of Delhi/ Indraprastha College for Women 12 247 ANAPURU SHRAVANI F KL College of Law, KL University 13 128 ANIKET WIISHRA M DES SHRI NAVALMAL FIRODIA LAW COLLEGE, PUNE 14 421 ANURAG SHANKAR M Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai 15 652 APARNA KP F GOVT . LAW COLLEGE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM 16 233 ARINDOWl BORA M Indian Institute Of technology, Guwahati 17 4 ARUNDHATI KISHOR F D.E.S Navalmal Firodia Law College, PAWAR Pune ( Fergusson College ) SRM School Of Law 18 411 ARYA DINESH F — S. No. jApplican Applicant_Name Gend |University_CollegeJnstitute t ID er 19 49 ARYA PATIL "f iGovernment Law College, Mumbai "jvj luiLS, Panjab University Regional 20 294 ASEEM KUMAR Centre 21 ASHMITA MITRA "f lAlliance University Bangalore Ivi INATIONAL LAW UNIVERCITY, 22 255 ASHOK SAGR