Worldwide Research on Geoparks Through Bibliometric Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of North American Geoparks

The Future of North American Geoparks Heidi Bailey and Wesley Hill Introduction Geoparks have proven to be highly successful in other parts of the world, particu- larly in Europe and China. The greatest strength of the geopark initiative is the attention it brings to earth heritage resources and the resulting socioeconomic development that occurs in rural areas. The future of the North American geoparks has yet to be decided. Because the geopark idea differs from other park concepts in North America, land managers and the pub- lic will likely have many questions about the program. This article addresses some of these questions and is intended to help further the discussion about the future of North American geoparks. What would be the structure of a North American geopark? A geopark is a destination identity similar in concept to a national heritage area. Geoparks are defined by the underlying geology of the landscape and transcend the boundaries of parks and other protected areas. A geopark operates as a partnership of people and land managers working to promote earth heritage through education and sustainable tourism. A North American geopark will not be a new category of protected area. The land remains entirely in the hands of local people and existing land management systems. Local, state, or national governments retain control of the public lands within a geopark. Private land remains in the hands of private owners. When an area is designated a geopark, it is man- aged through a bottom-up partnership approach. Does a geopark only focus on geology? A geopark is not just another geology park. -

Geological Parks, Eco-Tourism and Sustainable Development

3rd International Conference on Management Science and Management Innovation (MSMI 2016) Geological Parks, Eco-tourism and Sustainable Development Jian-Xinog Qin Institute of Regional Geography &Tourism Development, Southwest University for Nationalities, Chengdu, China E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—Based on the comparative analysis of the definition From the definition we can see, both in function and of geological parks, ecological tourism and sustainable purpose is consistent, and emphasize the following three development, this paper discusses the dialectical relationship binding: combination of local economic development and between the geological parks, ecological tourism and the protection of natural and cultural ecological system; sustainable development. The geological park is an important appreciate the nature and know the combination of nature; part of the ecological tourism resources, and the geological protection ecological environment and widespread public park is an important place and an ideal place for the awareness of protection combined. development of eco-tourism. Geological park and ecological tourism development has a similar goal system, development II. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE characteristics, development principles and contents. GEOLOGICAL PARK AND ECOLOGICAL TOURISM Geological park is an important part of the theory of sustainable development, is the embodiment of sustainable A. Geological relic resource is an important part of the tourism. The tourism development of geopark is a concrete ecological -

Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan2)

MALAYSIA NATIONAL PLAN OF ACTION FOR THE CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF SHARK (PLAN2) DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND AGRO-BASED INDUSTRY MALAYSIA 2014 First Printing, 2014 Copyright Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Department of Fisheries Malaysia. Published in Malaysia by Department of Fisheries Malaysia Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry Malaysia, Level 1-6, Wisma Tani Lot 4G2, Precinct 4, 62628 Putrajaya Malaysia Telephone No. : 603 88704000 Fax No. : 603 88891233 E-mail : [email protected] Website : http://dof.gov.my Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN 978-983-9819-99-1 This publication should be cited as follows: Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014. Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2), Ministry of Agriculture and Agro- based Industry Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia. 50pp SUMMARY Malaysia has been very supportive of the International Plan of Action for Sharks (IPOA-SHARKS) developed by FAO that is to be implemented voluntarily by countries concerned. This led to the development of Malaysia’s own National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark or NPOA-Shark (Plan 1) in 2006. The successful development of Malaysia’s second National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2) is a manifestation of her renewed commitment to the continuous improvement of shark conservation and management measures in Malaysia. -

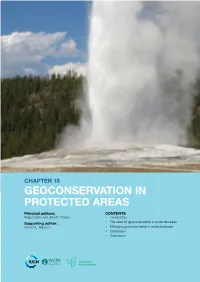

Geoconservation in Protected Areas Principal Authors: CONTENTS Roger Crofts and John E

Chapter 18 GeoconserVation in Protected Areas Principal authors: CONTENTS Roger Crofts and John E. Gordon • Introduction • The need for geoconservation in protected areas Supporting author: Vincent L. Santucci • Managing geoconservation in protected areas • Conclusion • References Principal AUTHORS ROGER CROFTS is an International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) Emeritus, was Founding CEO of Scottish Natural Heritage (1992– 2002), WCPA Regional Vice-chair for Europe (2000–08), and is Chair of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. JOHN E. GORDON is a Deputy Chair of the WCPA Geoheritage Specialist Group, and an honorary professor in the School of Geography & Geosciences, University of St. Andrews, Scotland, United Kingdom. Supporting AUTHOR VINCENT SANTUCCI is Senior Geologist and Palaeontologist with the US National Park Service, USA. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are grateful for helpful comments on the draft text from: Jay Anderson, Australia; Tim Badman, IUCN, Switzerland; José Brilha, University of Minho, Portugal; Margaret Brocx, Geological Society of Australia, Australia; Enrique Díaz-Martínez, Patrimonio Geológico y Minero (IGME), Spain; Neil Ellis, Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC), United Kingdom; Lars Erikstad, Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), Norway; Murray Gray, Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom; Bernie Joyce, University of Melbourne, Australia; Ashish Kothari, Kalpavriksh, India; Jonathan Larwood, Natural England, United Kingdom; Estelle Levin, Estelle Levin Limited, United Kingdom; Sven Lundqvist, Geological Survey of Sweden, Sweden; Colin MacFadyen, Scottish Natural Heritage, United Kingdom; Colin Prosser, Natural England, United Kingdom; Chris Sharples, University of Tasmania, Australia; Kyung Sik Woo, Kangwon National University, Korea and, Graeme Worboys, The Australian National University, Australia. Citation Crofts, R. -

A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution Yi Du, Yves Girault

A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution Yi Du, Yves Girault To cite this version: Yi Du, Yves Girault. A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution. In- ternational Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, Darswin Publishing House, 2018, 6 (2), pp.1-17. 10.17149/ijgp.j.issn.2577.4441.2018.02.001. hal-01974364 HAL Id: hal-01974364 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01974364 Submitted on 5 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks. 2018, 6(2): 1-17 DOI: 10.17149/ijgp.j.issn.2577.4441.2018.02.001 © 2018 Darswin Publishing House A Genealogy of UNESCO Global Geopark: Emergence and Evolution Yi Du, Yves Girault National Museum of Natural History, Paris, France The creation, in late 2015, of the UNESCO Global Geopark (UGG) label, as part of UNESCO’s patrimonialization system, was the outcome of a long process of negotia- tion between the United Nations Education Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO), an epistemic community (the International Union of Geological Sciences, IUGS) and the NGO Global Geopark Network (GGN). Today UNESCO Global Geo- parks are defined as “single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development”. -

A Sustainable (Culture Protecting) Tourism Indicator for Cultural and Environmental Heritage Tourism Initiatives

Asian Journal of Tourism Research Vol. 1, No. 2, December 2016, pp. 101-144 https: doi.org 10.12982 AJTR.2016.0017 A Sustainable (Culture Protecting) Tourism Indicator for Cultural and Environmental Heritage Tourism Initiatives David Lempert* Abstract: This article restores the international community’s goals for cultural sustainability and cultural protections in the context of tourism where it has been replaced by a concept of “sustainable tourism” that promotes exploitation of cultural resources but does little to protect and promote cultures and their environments. The article offers an indicator for screening government initiatives in cultural and environmental heritage tourism to assure that they meet the standards that are part of a global consensus in international laws and declarations. It offers a test of New Zealand Aid’s Tourism Project in Laos as an example of how the indicator can be used to expose failures in this field. Keywords: Tourism, Sustainability, Cultural Heritage, Environment Introduction There is a fundamental paradox at the heart of international tourism and efforts to protect it through “sustainable tourism” initiatives. While the attraction of international tourism is the value placed on cultural and environmental differences that are recognized and protected by a long list of international laws and treaties, the actual impacts of tourism, globalization and “growth” are to destroy cultural diversity and environments. While international organizations have created sets of standards and protections for “sustainable tourism”, the impact of these recommendations has been negligible. Placed together, the facts are startling. - Statistics suggest that one tenth of global GDP now comes from tourism and roughly the same amount of the global labor force (9%) works in tourism (Sharpley 2009, p.4). -

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 27 number 1 • 2010 Origins Founded in 1980, the George Wright Society is organized for the pur poses of promoting the application of knowledge, fostering communica tion, improving resource management, and providing information to improve public understanding and appreciation of the basic purposes of natural and cultural parks and equivalent reserves. The Society is dedicat ed to the protection, preservation, and management of cultural and natural parks and reserves through research and education. Mission The George Wright Society advances the scientific and heritage values of parks and protected areas. The Society promotes professional research and resource stewardship across natural and cultural disciplines, provides avenues of communication, and encourages public policies that embrace these values. Our Goal The Society strives to he the premier organization connecting people, places, knowledge, and ideas to foster excellence in natural and cultural resource management, research, protection, and interpretation in parks and equivalent reserves. Board of Directors ROLF DIA.MANT, President • Woodstock, Vermont STEPHANIE T(K)"1'1IMAN, Vice President • Seattle, Washington DAVID GKXW.R, Secretary * Three Rivers, California JOHN WAITHAKA, Treasurer * Ottawa, Ontario BRAD BARR • Woods Hole, Massachusetts MELIA LANE-KAMAHELE • Honolulu, Hawaii SUZANNE LEWIS • Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming BRENT A. MITCHELL • Ipswich, Massachusetts FRANK J. PRIZNAR • Gaithershnrg, Maryland JAN W. VAN WAGTENDONK • El Portal, California ROBERT A. WINFREE • Anchorage, Alaska Graduate Student Representative to the Board REBECCA E. STANFIELD MCCOWN • Burlington, Vermont Executive Office DAVID HARMON,Executive Director EMILY DEKKER-FIALA, Conference Coordinator P. O. Box 65 • Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA 1-906-487-9722 • infoldgeorgewright.org • www.georgewright.org Tfie George Wright Forum REBECCA CONARD & DAVID HARMON, Editors © 2010 The George Wright Society, Inc. -

IUGS Geoheritage Task Group

IUGS GeoHeritage Task Group Annual Report 2011 Plan of action for 2012 INTERNATIONAL UNION OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES (IUGS) 1. TITLE OF CONSTITUENT BODY IUGS Geoheritage task group 2. OVERALL OBJECTIVES Through the leadership of individuals and organizations with background in this particular issue, the IUGS Task Group on GeoHeritage works to facilitate the development of national and international awareness and understanding of the underlying concepts. The Task Group also helps to understand and recognize the various types of geosites (educative, recreative, protective …) around the world and to promote in developing countries the will to develop their own geoheritage. The Task Group works mainly through modern means of communication including discussions, meetings and information exchange via email and teleconferences, although some meetings may be required from time to time to anchor some decisions. As a consequence this group will function at little cost to IUGS and member organizations. Three main objectives addresses: 1- To develop an inventory of geoheritage sites. The large majority of these sites are isolated (a quarry, a single outcrop) and probably will never belong to any kind of geopark but they are valuable for education and for testimony of the history of the earth. Several organizations (national, disciplinary i.e. palaeontologists) are working or have the will to work on them. Their list and content should be available from any computer. 2- To compile the regulations on trade of ex-situ objects (fossils, mineral, meteorites) existing in different countries, which are usually difficult to obtain. The availability of this information on a website would be of a great help to geologist and other kind of people who have to deal with that matter (customs, …). -

An Exploration of Environmental Values in the Asian, Developing

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2016 An Exploration of Environmental Values in the Asian, Developing-World Context of Dong Van Karst Plateau Global Geopark, Vietnam Madeline Duda Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Duda, Madeline, "An Exploration of Environmental Values in the Asian, Developing-World Context of Dong Van Karst Plateau Global Geopark, Vietnam" (2016). All Theses. 2475. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2475 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXPLORATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL VALUES IN THE ASIAN, DEVELOPING-WORLD CONTEXT OF DONG VAN KARST PLATEAU GLOBAL GEOPARK, VIETNAM A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Management by Madeline Duda August 2016 Accepted by: Robert B. Powell, Committee Chair Jeffrey C. Hallo Brett A. Wright ABSTRACT It has been generally assumed that individuals’ environmental values are influenced by culture, experiences, social norms, economic standing, among others. However, to date research on held environmental values has focused primarily on the developed world context. To address this gap, this research explores the environmental values of -

Frequently Asked Questions About UNESCO Global Geoparks – General Information, Definitions, Governance and Framing Issues

FAQs general public Frequently asked questions about UNESCO Global Geoparks – General information, definitions, governance and framing issues What is a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Definition • What are the aims of a UNESCO Global Geopark? • What are the essential factors to be considered before creating a UNESCO Global Geopark? • How are UNESCO Global Geoparks established and managed? • Has a UNESCO Global Geopark a required minimum or a maximum size? • Is a UNESCO Global Geopark a new category of protected area? • Is there a limited number of UNESCO Global Geoparks within any one country? • What are typical activities within a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Do UNESCO Global Geoparks do scientific research? • What does community involvement and empowerment entail in a UNESCO Global Geopark? • How does a YNESCO Global Geopark deal with natural resources? • Can industrial activities and construction projects take place in a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Is the selling of any original geological material (e.g. rocks, minerals, and fossils) permitted within a UNESCO Global Geopark? • What to do if a National Geoparks Network exists in a country? • What is the Global Geoparks Network? UNESCO Global Geoparks among UNESCO designations and the role of UNESCO • What is the difference between UNESCO Global Geoparks, Biosphere Reserves and World Heritage Sites? • What is the role of UNESCO? • Does UNESCO provide training courses? What is a UNESCO Global Geopark? • Definition UNESCO Global Geoparks are single, unified geographical areas where sites and landscapes of international geological significance are managed with a holistic concept of protection, education and sustainable development. A UNESCO Global Geopark comprises a number of geological heritage sites of special scientific importance, rarity or beauty. -

Izu Peninsula Geopark Promotion Council

Contents A. Identification of the Area ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 A.1 Name of the Proposed Geopark ........................................................................................................................................... 1 A.2 Location of the Proposed Geopark ....................................................................................................................................... 1 A.3 Surface Area, Physical and Human Geographical Characteristics ....................................................................................... 1 A.3.1 Physical Geographical Characteristics .......................................................................................................................... 1 A.3.2 Human Geographical Charactersitics ........................................................................................................................... 3 A.4 Organization in charge and Management Structure ............................................................................................................. 5 A.4.1 Izu Peninsula Geopark Promotion Council ................................................................................................................... 5 A.4.2 Structure of the Management Organization .................................................................................................................. 6 A.4.3 Supporting Units/ Members -

Environmental, Cultural, Economic, and Social Sustainability

Eleventh International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic, and Social Sustainability 21–23 JANUARY 2015 | SCANDIC HOTEL COPENHAGEN COPENHAGEN, DENMARK | ONSUSTAINABILITY.COM Sustainability Conference 1 Dear Delegate, The Sustainability knowledge community is an international conference, a cross-disciplinary scholarly journal, a book imprint, and an online knowledge community which, together, set out to describe, analyze and interpret the role of Sustainability. These media are intended to provide spaces for careful, scholarly reflection and open dialogue. The bases of this endeavour are cross- disciplinary. The community is brought together by a common concern for sustainability in an holistic perspective, where environmental, cultural, economic and, social concerns intersect. In addition to organizing the Sustainability Conference, Common Ground publishes papers from the conference at http://onsustainability.com/publications/journal. We do encourage all conference participants to submit an article based on their conference presentation for peer review and possible publication in the journal. We also publish books at http://onsustainability.com/publications/books, in both print and electronic formats. We would like to invite conference participants to develop publishing proposals for original works or for edited collections of papers drawn from the journal which address an identified theme. Finally, please join our online conversation by subscribing to our monthly email newsletter, and subscribe to our Facebook, RSS, or Twitter feeds at http://onsustainability.com. Common Ground also organizes conferences and publishes journals in other areas of critical intellectual human concern, including diversity, museums, technology, humanities and the arts, to name several (see http://commongroundpublishing.com). Our aim is to create new forms of knowledge community, where people meet in person and also remain connected virtually, making the most of the potentials for access using digital media.