ANNEX1 ICC-02/05-01/09-27-Anx1 21-07-2009 2/45 IO PT OA World Affairs Journal - Case Closed: a Prosecutor Without Borders Page 1Of8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Closed, Vol. 27 Ebook Free Download

CASE CLOSED, VOL. 27 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 29 Oct 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421516790 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed, Vol. 27 PDF Book January 20, [22] Ai Haibara. Views Read Edit View history. Until Jimmy can find a cure for his miniature malady, he takes on the pseudonym Conan Edogawa and continues to solve all the cases that come his way. The Junior Detective League and Dr. Retrieved November 13, January 17, [8]. Product Details. They must solve the mystery of the manor before they are all killed off or kill each other. They talk about how Shinichi's absence has been filled with Dr. Chicago 7. April 10, [18] Rachel calls Richard to get involved. Rachel thinks it could be the ghost of the woman's clock tower mechanic who died four years prior. Conan's deductions impress Jodie who looks at him with great interest. Categories : Case Closed chapter lists. And they could have thought Shimizu was proposing a cigarette to Bito. An unknown person steals the police's investigation records relating to Richard Moore, and Conan is worried it could be the Black Organization. The Junior Detectives find the missing boy and reconstruct the diary pages revealing the kidnapping motive and what happened to the kidnapper. The Junior Detectives meet an elderly man who seems to have a lot on his schedule, but is actually planning on committing suicide. Magic Kaito Episodes. Anime News Network. Later, a kid who is known to be an obsessive liar tells the Detective Boys his home has been invaded but is taken away by his parents. -

Protoculture Addicts

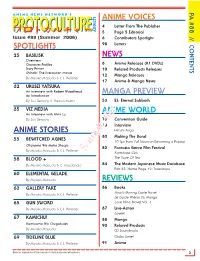

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Justice to the Extent Possible: the Prospects for Accountability in Afghanistan

KHAN GALLEY 1.0 11/18/2010 5:40:51 PM JUSTICE TO THE EXTENT POSSIBLE: THE PROSPECTS FOR ACCOUNTABILITY IN AFGHANISTAN Nadia Khan* I. INTRODUCTION Justice in Afghanistan, in the wake of nearly three decades of war, is a com- plicated endeavor – further complicated by the Afghan government’s recent grant of amnesty to perpetrators of past crimes. This paper will attempt to establish the prospects for accountability in Afghanistan, in light of the country’s historical cy- cles of war and violence and the recent attempts to trade justice for peace. The his- torical foundation will first be laid to demonstrate the complexities of the Afghan conflict and the fragility of the current regime. The steps that have been taken to- wards establishing a transitional justice framework are then set out to illustrate the theoretical objectives that stand in sharp contrast to the government’s actual intran- sigence to justice and accountability. The latter being demonstrated most signifi- cantly in the amnesty law signed into effect on February 20, 2007, that may ulti- mately be considered illegal at international law. However, the illegality of amnesty does not answer the question of account- ability for Afghans, since current circumstances and the government’s self-interest suggest that it will continue in effect. Thus, alternatives are considered, both do- mestically and internationally – with only one avenue producing the most realistic prospect for justice and accountability. It suggests that justice in Afghanistan is not entirely impossible, in spite of the increasing instability and in spite of the am- nesty. Although the culture of impunity in Afghanistan has been perpetuated on the pretext of peace – it has become all too clear that true peace will require jus- tice. -

Building a Legacy: Lessons Learnt from the Offices of the Prosecutors of International

Building a Legacy Lessons Learnt from the Offices of the Prosecutors of International Criminal Tribunals and Hybrid Courts International Conference 7–8 November 2013 in Nuremberg Conference Report by Viviane Dittrich Introduction The following is a report of the proceedings of the conference entitled “Building a Legacy – Lessons Learnt from the Offices of the Prosecutors of International Criminal Tribunals and Hybrid Courts” which was held at the Memorium Nuremberg Trials on 7 and 8 November 2013. This report is designed to summarize the main arguments made in each presentation and to capture the key points of discussion. We have also identified some questions that remain salient. The conference explored the timely topic of impact and legacy of the International Criminal Tribunals and Courts from the perspective of the prosecution of international crimes. As the Ad hoc Tribunals and Hybrid Courts are working towards completing their last cases and winding down, the conference provided an international forum to capture and extend the important discussions on their achieve- ments, contributions and lessons learnt regarding the selection of cases and investigations, the completion of mandates and partnerships between national and international jurisdictions. There were a number of reasons to organize a conference on this topic. Following the successful conference “Through the Lens of Nuremberg: The International Criminal Court at Its Tenth Anniversary” held in Nuremberg in October 2012 which indirectly touched upon the topic of legacy, it seemed apposite to hold a conference dedicated entirely to a discussion on the impact and legacy of the different tribunals at the international and national level. -

The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T

MIGRATION,PALGRAVE ADVANCES IN CRIMINOLOGY DIASPORASAND CRIMINAL AND JUSTICE CITIZENSHIP IN ASIA The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y.C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Refecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the feld of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 David T. Johnson The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson University of Hawaii at Mānoa Honolulu, HI, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-030-32085-0 ISBN 978-3-030-32086-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32086-7 This title was frst published in Japanese by Iwanami Shinsho, 2019 as “アメリカ人のみた日本 の死刑”. [Amerikajin no Mita Nihon no Shikei] © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. -

Fifteen Years of Outreach at the ICTY

OUTR ACH 15 years of Outreach at the ICTY A publication of the Outreach Programme, Registry, ICTY Editor-in-Chief: Giorgia Tortora Managing editor: Rada Pejić-Sremac Editors: Joanna Ellis Adwan and Nenad Golčevski The ICTY Outreach Programme Managing editors for the OTP: Kevin Hughes and Ljiljana Vodenski-Piteša is generously supported by the Graphics editor: Leslie Hondebrink-Hermer European Union. Photographs: ICTY Outreach Programme and Leslie Hondebrink-Hermer Contributors: Almir Alić, Ernesa Ademagić, Giulia Chiara, Steve Coulson, Petar Dubljević, Helena Eggleston, Amy Eussen, Petar Finci, Goran Georgijev, Amanda Molesworth, Thomas Rivière, Ana Cristina Rodríguez Pineda, Catina Tanner, Isabella Tan Hui Huang Proofreading: Joanna Ellis Adwan and Conference and Language Services Section Circulation: 1,000 copies Printed in The Netherlands, 2016 Special thanks go to all Outreach staff, past and present, who made the work of the Outreach Programme possible. The editors are especially grateful to Mr Matias Hellman, former Outreach representative, for providing insights into the early days of the Outreach Programme and his assistance in researching the Programme’s history. Last but not least, the editors would also like to thank the Principals of the Tribunal and their staff for their invaluable support they have been providing to the Programme and their endorsement of this project. This publication makes use of QR codes (Quick Response code) to expand the reading experience. Where available, these will bring you to the related webpage -

International Court of Justice (ICJ)

SRMUN ATLANTA 2018 Our Responsibility: Facilitating Social Development through Global Engagement and Collaboration November 15 - 17, 2018 [email protected] Greetings Delegates, Welcome to SRMUN Atlanta 2018 and the International Court of Justice (ICJ). My name is Lydia Schlitt, and I will be serving as your Chief Justice for the ICJ. This will be my third conference as a SRMUN staff member. Previously, I served as the Director of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) at SRMUN Atlanta 2017 and the Assistant Director (AD) of the Group of 77 (G-77) at SRMUN Atlanta 2016. I am currently a Juris Doctorate candidate at the University of Oregon School of Law and hold a Bachelor’s of Science with Honors in Political Science and a minor in Mathematics from Berry College. Our committee’s Assistant Chief Justice will be Jessica Doscher. This will be Jessica’s second time as a staff member as last year she served as the AD for the General Assembly Plenary (GA Plen). Founded in 1945, the ICJ is the principal legal entity for the United Nations (UN). The ICJ’s purpose is to solve legal disputes at the request of Member States and other UN entities. By focusing on the SRMUN Atlanta 2018 theme of “Our Responsibility: Facilitating Social Development through Global Engagement and Collaboration," throughout the conference, delegates will be responsible for arguing on the behalf of their assigned position for the assigned case, as well as serving as a Justice for the ICJ for the remaining cases. The following cases will be debated: I. -

Protoculture Addicts Is ©1987-2006 by Protoculture • the REVIEWS Copyrights and Trademarks Mentioned Herein Are the Property of LIVE-ACTION

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ P r o t o c u l t u r e A d d i c t s # 8 7 December 2005 / January 2006. Published by Protoculture, P.O. Box 1433, Station B, Montreal, Qc, Canada, H3B 3L2. ANIME VOICES Letter From The Publisher ......................................................................................................... 4 E d i t o r i a l S t a f f Page Five Editorial ................................................................................................................... 5 [CM] – Publisher Christopher Macdonald Contributor Spotlight & Staff Lowlight ......................................................................................... 6 [CJP] – Editor-in-chief Claude J. Pelletier Letters ................................................................................................................................... 74 [email protected] Miyako Matsuda [MM] – Contributing Editor / Translator Julia Struthers-Jobin – Editor NEWS Bamboo Dong [BD] – Associate-Editor ANIME RELEASES (R1 DVDs) ...................................................................................................... 7 Jonathan Mays [JM] – Associate-Editor ANIME-RELATED PRODUCTS RELEASES (UMDs, CDs, Live-Action DVDs, Artbooks, Novels) .................. 9 C o n t r i b u t o r s MANGA RELEASES .................................................................................................................. 10 Zac Bertschy [ZB], Sean Broestl [SB], Robert Chase [RC], ANIME & MANGA NEWS: North -

The Hague Espace for Environmental Global Governance

I NSTITUTE FOR E NVIRONMENTAL S ECURITY Study on The Hague Espace for Environmental Global Governance Wybe Th. Douma ❘ Leonardo Massai ❘ Serge Bronkhorst ❘ Wouter J. Veening Volume One - Report May 2009 STUDY ON THE HAGUE ESPACE FOR ENVIRONMENTAL GLOBAL GOVERNANCE VOLUME ONE - REPORT May 2009 Study on The Hague Espace for Environmental Global Governance Volume One - Report Authors: Wybe Th. Douma - Leonardo Massai - Serge Bronkhorst - Wouter J. Veening Published by: Institute for Environmental Security Anna Paulownastraat 103 2518 BC The Hague, The Netherlands Tel: +31 70 365 2299 ● Fax: +31 70 365 1948 www.envirosecurity.org In association with: T.M.C. Asser Institute P.O. Box 30461 2500 GL The Hague, The Netherlands Tel: +31 70 342 0300 ● Fax: +3170 342 0359 www.asser.nl With the support of: City of The Hague The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs The Netherlands Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment Project Team: Wouter J. Veening, Chairman / President, IES Ronald A. Kingham, Director, IES Serge Bronkhorst, Bronkhorst International Law Services (BILS) / IES Jeannette E. Mullaart, Senior Fellow, IES Prof. Dr. Frans Nelissen, General Director, T.M.C. Asser Institute Dr. Wybe Th. Douma, Senior Researcher, European Law and International Trade Law, T.M.C. Asser Institute Leonardo Massai, Researcher, European Law, T.M.C. Asser Institute Marianna Kondas, Project Assistant, T.M.C. Asser Institute Daria Ratsiborinskaya, Project Assistant, T.M.C. Asser Institute Cover design: Géraud de Ville, IES Copyright © 2009 Institute for Environmental Security, The Hague, The Netherlands ISBN: ________________ NUR: ________________ All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this publication for education and other non- commercial purposes are authorised without any prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the authors and publisher are fully acknowledged. -

Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository ALL THE EVIL OF GOOD: PORTRAYALS OF POLICE AND CRIME IN JAPANESE ANIME AND MANGA By Katelyn Mitchell Honors Thesis Department of Asian Studies University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill April 23, 2015 Approved: INGER BRODEY (Student’s Advisor) 1 “All the Evil of Good”: Portrayals of Police and Crime in Japanese Anime and Manga By Katelyn Mitchell “Probity, sincerity, candor, conviction, the idea of duty, are things that, when in error, can turn hideous, but – even though hideous, remain great; their majesty, peculiar to the human conscience, persists in horror…Nothing could be more poignant and terrible than [Javert’s] face, which revealed what might be called all the evil of good” -Victor Hugo, Les Misérables Volume I, Book VIII, Chapter III: “Javert Satisfied” Abstract This thesis examines and categorizes the distinct, primarily negative, portrayals of law enforcement in Japanese literature and media, beginning with its roots in kabuki drama, courtroom narratives and samurai codes and tracing it through modern anime and manga. Portrayals of police characters are divided into three distinct categories: incompetents used as a source of comedy; bland and consistently unsuccessful nemeses to charismatic criminals, used to encourage the audience to support and favor these criminals; or cold antagonists fanatically devoted to their personal definition of ‘justice’, who cause audiences to question the system that created them. This paper also examines Western influences, such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and Victor Hugo’s Inspector Javert, on these modern media portrayals. -

The International Law of War Crimes (Ll211)

THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF WAR CRIMES (LL211) Course duration: 54 hours lecture and class time (Over three weeks) LSE Teaching Department: Department of Law Lead Faculty: Professor Gerry Simpson (Dept. of Law) Pre-requisites: Introduction to legal methods or equivalent. (Basic legal knowledge is a requirement. This would be satisfied by, among other things, Professor Lang’s LL105 course in the previous session). Introduction The following provides a course outline, list of lecture topics and sample readings. Use the list to familiarize yourself with the range and type of materials that will be used. Please note that the full reading lists and tutorial discussion questions will be provided at the start of the course. Welcome to this Summer School course in The International Law of War Crimes. The course will consist of twelve three-hour lectures and twelve one-and-a-half-hour classes. It will examine the law and policy issues relating to a number of key aspects of the information society. 1 The course examines, from a legal perspective, the rules, concepts, principles, institutional architecture, and enforcement of what we call international criminal law or international criminal justice, or, sometimes, the law of war crimes. The focus of the course is the area of international criminal law concerned with traditional “war crimes” and, in particular, four of the core crimes set out in the Rome Statute (war crimes, torture as a crime against humanity, genocide and aggression). It adopts an institutional (Nuremberg, Rwanda, the Former Yugoslavia), philosophical (Arendt, Shklar) and practical (the ICC) focus throughout. There will be a particular focus on war crimes trials and proceedings e.g. -

Methods of the International Criminal Court and the Role of Social Media

Methods of the International Criminal Court and the Role of Social Media Stefanie Kunze Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, AZ [email protected] April 2014 Introduction In the 20th century crimes against humanity and crimes of war have become more present in our conscience and awareness. The reasons are that they have become more methodical, more devastating, and also better documented. The 20th century has seen a development from international awareness of international crime and human rights violations, to the establishment of international criminal tribunals and ultimately the establishment of the International Criminal Court, and an undeniable influence of social media on the international discourse. Genocide is one of these crimes against humanity, and arguably the gravest one. With ad-hoc international and national criminal tribunals, special and hybrid courts, as well as the permanent International Criminal Court (ICC), big steps have been taken towards justice in the wake of genocide and crimes against humanity. Genocide is hardly a novel crime; it is the name that was newly coined in the mid-1900s. In fact, mass killings and possible genocide have occurred for centuries. The mass killing under Russian leader Stalin1 (Appendix A) occurred before the height of the Nazi Holocaust. Even before then, mass atrocities were committed over time, though not well documented. For instance the Armenian genocide under the Ottoman Empire, has been widely accepted as a “true” genocide, with roughly one-and-a-half-million dead.2 To this day Turkey denies these numbers.3 With the end of World War II and the end of the Nazi regime, the first international tribunals in history were held, prosecuting top-level perpetrators.