Spring/Summer 2019 $12.50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Firing Squad

Che rife CwwwnM SUGAR. 96 17. S. WEATHER BUREAU, JULY 10. Last 2i hours' rainfall. Test Centrifugals, 4.1025c.; Per Ton, $82.0!. Trace. Temperature, Max. 82; Min. 72. Weather. Fair. 88 Analysis Beets 10s. 5 Per Ton $85.00. ESTABLISHED JULY ? 1656 VOL. XLII., NO. 7152. HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, TUESDAY. JULY 11, 1905. price five euro. RUSSIAN CONVICTS AT SAGHALIEN MUTINY IN A FIRING SQUAD V 0 Execution Party Refuses to Fire on Condemned Men and Shoots Officers Instead. (ASSOCIATED PRESS OABLEOKAKS.) LONDON, July 11. It is reported that 23 mutineers at Libau were condemned to death. The firing squad detailed to execute them mutinied, turned about and shot twelve officers. Cossacks were summoned and in the fight that followed 30 were killed. SEBASTOPOL, July 11. The torpedo boat in the hands of the mutineers has refused to surrender. The Kustenji has arrived and its crew has been arrested. THE JAPANESE INVASION OF SAGHALIEN ISLAND TOKIO, July 11. The Russian forces have withdrawn into the interior of Saghalien. Many Russian political prisoners have been set free by the Japanese troops. CONSULAR REPORTS. WASHINGTON, July 10th, 1905. To the JAPANESE CONSUL GENERAL, Honolulu: Admiral Kataoka's report runs as follows: Our squadron arrived in the Saghalien waters at - daybreak of the 7th, inst., and after sea-cleari- operations, our transports and a part of the squadron approached the coast. Our squadron arrived in the Saghalien waters at daybreak of the 7th, cupied the position as was previously determined; thereupon a part of our army also landed and relieved the naval detachment. -

London Coffee Houses : the First Hundred Years Heather Lynn Mcqueen

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 2004 London coffee houses : the first hundred years Heather Lynn McQueen Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation McQueen, Heather Lynn, "London coffee houses : the first hundred years" (2004). Honors Theses. Paper 283. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. London Co_ffee Houses: The First Hundred Years An Honors Thesis Submitted To ,. ''·''"~ • . The Faculty of The Department of History Written Under the Direction of Dr. John Gordon By HEATHER LYNN McQUEEN Richmond, Virginia April 19, 2004 I pledge that I have neither given nor received any unauthorized assistance during the completion ofthis work. Abstract This paper examines how early London coffee houses catered to the intellectual, political, religious and business communities in London, as well as put forward some information regarding what it was about coffee houses that made them "new meeting places" for Londoners. Coffee houses offered places for political debate and progressively modem forms of such debate, "penny university" lessons on all matter of science and the arts, simplicity and sobriety in which independent religious groups could meet, as well as the early development of a private office space. Preface I remember as a child watching my parents pouring themselves mugs of coffee each morning, the smell of the beans filling the kitchen, and since these early sights and smells, the world of coffee has been an intriguing, interesting, exotic, and informational part of my life. -

Quarter!Yjvews

Quarter!yJVews VOL. 28, NO.2 PUBLISHED BY LONG YEAR MUSEUM AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 1991 CAROL NORTON "Because he represented a noble type of true manhood he was keenly appreciative of the advancing idea of true womanhood, and ever held in the highest reverence our beloved Leader. ... " From a tribute to Norton in The Christian Science Journal, May 1904 Carol Norton On the afternoon of December 18, Norton, spoke extemporaneously for and that he handled his subject "in a 1898, an unassuming but earnest over an hour and a half, and "held the masterly manner. " 3 young man, still in his twenties, close attention of his vast audience .... Norton's lecture was presented at addressed an audience of over 3,000 He declared that the philosophy of a time when Christian Science was people at Carnegie Hall in New York Christian Science would stand the test being viciously attacked by the press, City on the subject of Christian Sci of time; that it proved its accuracy and this was no doubt the reason that ence. Prominent clergymen were in by its results, and demonstrated its all but one New York newspaper attendance, and a physician of the divinity from the Bible .... " 1 ignored the event in their columns. allopathic and homeopathic schools We cannot know how the distin Just six months later, however, it'was was seated on the platform. The only guished audience responded to such a different story. Norton's appearance New York newspaper that reported the statements as: "The restored Church of at the Metropolitan Opera House on event stated that the lecturer, Carol Christ on earth is rising in our midst''; May 28, 1899 was reported by every and '' .. -

Portland Daily Press. Estabusmedjene 23

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. ESTABUSMEDJENE 23. 1868. TO), H. M0NDA7' MORNING. APRIL 13. 1874. _PORTLAND. rERMStS.OO PER ..NNH. IN IDTAKrY THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS CARDS. BUSINESS TO LEI. REAL ESTATE. WANTS. COPARTNERSHIP. have Published every day (Sundays THE thought all along that the time for act excepted) by the PRESS. ing on it might probably come. I think the PORTLAND MOTLEY dc BLETHEN, . House Wanted. PUBLISHING CO., TO LET! FOR SALE. ha? «>«« now. I wish it was a better \ HOUSE with or ten rooms for a family of Copartnership Notice. MONDAY MORNING, APRIL. 18. 1874 { eight ***at we were in abetter condi- At 109 Exchange St. Pobtland. ATTORNIES AT Pleasant Rooms With Board, XA. three without children. Rent not to exceed tinrf' 'ri,Wl'lh LAW. Fittle Chebesgae-The Moat Beautiful « fthe $500. Apply to CARTER BROS., corner Casco ek hi.n armv against the reb- Terms : of all the Islands of Casco Bay. From the Boston Journal. fk!1™ Eight Dollars a Year in advauce. Tc 40 1-0 EXCHANGE nolOeodtf At 30* High St., S. S. KNIoHT. and Congress streets. aprleod*2w wlllt Isbould have best mall subscribers Seven Dollars a in au- STREET, It contains one hundred and for- hked Rm“ lUiU! Year if paid Profits of Farming, etc. drivc» out ol Ma ▼anee. ty acres of land, thirty of which is ROUNDS & DYER rv and ami p‘ey haye bfei? (Over Dresser & McLellan’s Rooms to Let. Wanted. is no Book Store.) covered with a beautiful Grove. I have received a copy of a Lynn paper, „„ Pennsylvania longer in dan- or unfurnished rooms to let in a The balance is the of til- FIRST CLASS the THE MAINE PRE’SS very best FURNITURE PAINTER, one with an article on “The Profits of ««bel a™>y was STATE Wm. -

Montana Crowds of People Gathered on the Streets on That Fatal Tuesday

Montana, 11-12, p.1 Montana Crowds of people gathered on the streets on that fatal Tuesday. No one knew where it had come from; no one knew why, but everyone had heard the rumor, and everyone was curious for more information. A panic swept the state as they gossiped nervously. Many people were rifling frantically through Bibles, while others looked at the sky, wondering if a storm was to come. Still others hurriedly ushered their families out of state, hoping to avoid that terrible tragedy to come. No one was working, no one was having fun, no one was sleeping; everyone whispered among themselves, wondering quietly but not daring to speak aloud. It all started the day before, early that morning as the sun went up. John Smith woke up and, very normally, showered, brushed his teeth, shaved and dressed. He just as normally ate breakfast, grabbed a couple of pieces of toast to eat and poured himself a glass of orange juice, and walked out the door towards his newspaper-editing office. He reached his office and found, just as usual, the three newspapers other editors had published in the same city. John spread the newspapers on his desk (still very normally) and smoothed them out to read, but the headline of the first newspaper caused him to choke on his own saliva. He adjusted his glasses and smoothed the paper out to be sure he was reading it correctly. John was not mistaken, however, and he shook his head after reading the article, disturbed, as he hurried out of his office to his secretary. -

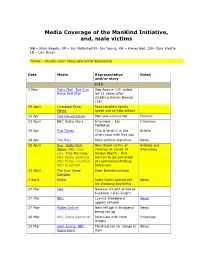

Media Coverage of the Mankind Initiative, And, Male Victims

Media Coverage of the ManKind Initiative, and, male victims MB – Mark Brooks, IM – Ian McNicholl,IY- Ian Young, KB – Kieron Bell, SW- Sara Westle LB – Lori Busch Yellow – denote court cases and initial disclosures Date Media Representative Detail and/or story 2018 3 May Daily Mail, The Sun, Zoe Adams (19) jailed News and Star for 11 years after stabbing Kieran Bewick (18) 29 April Liverpool Echo, Paul Lavelle’s family Metro speak out to help others 26 Apr The Conversation Men are victims too Feature 23 April BBC Radio Worc Interview – Ian Interview McNicholl 19 Apr The Times This is what it is like Article when your wife hits you 18 Apr The Sun Male victims statistics News 16 April Sun, Daily Mail, Alex Skeel victim of Articles and Metro, BBC Five violence at hands of interviews Live, This Morning, Jordan Worth - first BBC Radio Scotland, woman to be convicted BBC Three Counties, of coercive/controlling BBC Breakfast behaviour 13 April The Sun (Dear Dear Deirdre column Deirdre) 7 April Mirror Jodie Owen spared jail News for stabbing boyfriend 29 Mar Mail Nasreen Knight attacked husband Julian knight 27 Mar BBC Lavinia Woodward News appeal refused 27 Mar Wales Online New refuge in Bridgend News being set up 26 Mar BBC Radio Somerset Interview with Mark Interview Brooks 23 Mar Kent online, BBC ManKind call for refuge in News Radio Kent Kent 14-16 Mar Stoke Sentinel, BBC Pete Davegun fundraiser Radio Stoke, Crewe Guardian, Staffs Live 19 Mar Victoria Derbyshire Mark Brooks interview Interview 12 Mar Somerset Live ManKind Initiative appeal -

Portland Daily Press: December 4, 1875

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 1862. VOL. 13. 23, PORTLAND. SATURDAY MORNING. DECEMBER 4, 1875. TEEMS $8.00 PER ANNUM, IN ADVANCE. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, of our civilization since wo became a BUSINESS CARDS. MISCELLANEOUS. THE PRESS. nation Recent Publications. know the daily life of which they were the result. Published every day (Sundays excepted) by the —that a new opera by M. Offenbach has been But this reason does not exist in the case of the demanded ? If it is not as an emblem of The Shepherd Lady; and other Poems. By memoir of Miss Fletcher, and its PORTLAND PUBLISHING CO., CHARLES H. SATURDAY HORNING. DEC. 4, 1S75 publication KIMBALL, but as one of Jean Ingelow. Published by Roberts Brothers: seems to encroach the reserve At 109 Exchange Sr., Portlakd. progress, simply example the somewhat upon of Boston. For sale by Loring, Short & Harmon. that was the The volume is a Year in ARCHITECT OI K BANNERS Every many phases present civilization that the young girl’s right. Terms: advance. WE UNFURL attache of the is Eight Dollars To regular Press furnished A volume, mail a Year if in charming holiday profusely illus- carefully arranged and a added to its subscribers Seven Dollars paid ad- ISO 1-2 MIDDLE STREET, with a Card certificate countoreigned by Stanley T. opera bouffe was to be presented, an ele- chapter vance. trated and containing poems not included in contents a member of Mrs. Fletcher’s fam- (Bojrd Bloolr,) Pullen, Editor. All railway, steamboat and hotel gantly upholstered or a su- by drinking-saloon aoy of Miss books. -

UK & Foreign Newspapers

25th January 2016 UK & Foreign Newspapers UK National Newspapers Please Note Titles marked (ND) are not available for digital copying other than via direct publisher licence. This is the complete list of titles represented by NLA. Your organisation is responsible for advising NLA, or its representative, of the titles you wish to elect and include in your licence cover. The NLA licence automatically includes cover for all UK National Newspapers and five Regional Newspapers. Thereafter you select additional Specialist, Regional and Foreign titles from those listed. Print titles Daily Mail Independent on Sunday The Financial Times (ND) Daily Mirror Observer The Guardian Daily Star Sunday Express The Mail on Sunday Daily Star Sunday Sunday Mirror The New Day Evening Standard Sunday People The Sun i The Daily Express The Sunday Telegraph Independent The Daily Telegraph The Sunday Times The Times Websites blogs.telegraph.co.uk www.guardian.co.uk www.thescottishsun.co.uk fabulousmag.thesun.co.uk www.independent.co.uk www.thesun.co.uk observer.guardian.co.uk www.mailonsunday.co.uk www.thesun.ie www.dailymail.co.uk www.mirror.co.uk www.thesundaytimes.co.uk www.dailystar.co.uk www.standard.co.uk www.thetimes.co.uk www.express.co.uk www.telegraph.co. -

MARCH 2017 Publication Change Fieldwork Period on Which Publishe

PUBLICATION CHANGES DURING THE FIELDWORK PERIOD: APRIL 2016 – MARCH 2017 Publication Change Fieldwork period on which published figures are based 220 Triathlon Launched April 1989. Added No figures in this report. to the questionnaire April 2016. BBC Countryfile Launched October 2007. No figures in this report. Added to the questionnaire April 2016. Cycling Plus Launched January 1992. No figures in this report. Added to the questionnaire April 2016. Mountain Biking UK Launched January 1988. No figures in this report. Added to the questionnaire April 2016. It is the publishers’ responsibility to inform PAMCo as soon as possible of any changes to their titles included in the survey. The following publications were included in the questionnaire for all or part of the reporting period. For methodological or other reasons, no figures are reported. All about Soap Lonely Planet Magazine The Spectator Amateur Photographer Love It! Sport Asian Woman Match! Stylist ASOS MBR Mountain Bike Rider Sunday Independent (Plymouth) BBC Focus Mixmag Sunday Mercury (Birmingham) Candis Moneywise Sunday Sun (Newcastle) Classic and Sportscar The Mother Superbike Magazine The Classic MotorCycle National Geographic T3 Coach Natural Health TNT Magazine Conde Nast Traveller Nature’s Home Top of the Pops Magazine Digital Camera The New Day Top Sante Digital Photo New Scientist Total Film The Economist Next Trout Fisherman Essentials Perfect Wedding Viz F1 Racing Prima Baby & Pregnancy Wales on Sunday Film Review Psychologies Magazine The Weekly News Financial Times -

Are UK Newspapers Really Dying? a Financial Analysis of Newspaper Publishing Companies

Journal of Media Business Studies ISSN: 1652-2354 (Print) 2376-2977 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/romb20 Are UK newspapers really dying? A financial analysis of newspaper publishing companies Marc Edge To cite this article: Marc Edge (2019): Are UK newspapers really dying? A financial analysis of newspaper publishing companies, Journal of Media Business Studies To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2018.1555686 Published online: 04 Feb 2019. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=romb20 JOURNAL OF MEDIA BUSINESS STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2018.1555686 Are UK newspapers really dying? A financial analysis of newspaper publishing companies Marc Edge Department of Media and Communications, University of Malta, Msida, Malta ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This research follows on a 2014 study of North American newspapers Received 30 June 2017 which examined annual financial reports for publicly traded chains and Accepted 28 November 2018 found that none posted an annual loss on an operating basis between KEYWORDS 2006 and 2013. An analysis of UK newspaper company financial Newspapers; UK media; reports was thus performed to determine whether predictions of future of journalism extinction similar to those made in North America are likewise unfounded and to compare their performance. Results showed more variation than in the U.S. and Canada. Most UK newspapers are still profitable, but not as profitable as before. The Times, historically a loss maker, has moved to profitability in recent years with the introduction of a paywall for its online content. -

New Facility Offers New Day for Mental Health Services for Sumter Residents

No resolution ultimately lasted from 9:30 a.m. April after serving as interim Clarendon coroner to 4 p.m., was originally a result coroner since January after the of Clarendon County Coroner late Samuels Hayes died, has 22 hearing to continue Bucky Mock filing a lawsuit years’ experience as a death in- claiming LaNette Samuels-Coo- vestigator and has worked as into next week per, who beat Mock deputy coroner in in the June 12 pri- Clarendon County for SUNDAY, JULY 22, 2018 $1.75 BY KAYLA ROBINS mary, is not quali- 21 years. [email protected] fied to be a coroner Samuels-Cooper, the SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 in South Carolina sister of Hayes, has In what seems to be turning into and incorrectly said on the record pre- a chicken or the egg situation at marked she had one viously she has not led the Clarendon County Court- year’s experience in MOCK SAMUELS- a death investigation house, a merit hearing about death investigation COOPER but that her 13 years of whether the winner of the Demo- with a law enforce- working as an adminis- cratic primary for coroner can re- ment agency, coroner or medical trative assistant in the coroner’s 4 SECTIONS, 28 PAGES | VOL. 123, NO. 196 main on the ballot will spill into examiner agency. office and at her brother’s funeral next week. Mock, who was appointed coro- WORLD The hearing on Friday, which ner by Gov. Henry McMaster in SEE CORONER, PAGE A10 ‘To everything there is a season ...’ (ECCLESIASTES 3:1) New facility offers new day for mental health services for Sumter residents Thailand seeks control over movies about rescue Military government concerned about portrayal of boys trapped in cave A4 SPORTS P-15’s rally in wild 6-4 win over Camden, head PHOTOS BY BRUCE MILLS / THE SUMTER ITEM Santee-Wateree Community Mental Health Center staff member Patrice Lloyd, right, shows guests a children’s play room to state tourney B1 area on Thursday at the new center. -

New Day Barely Dawned: Here's Why UK's Latest Paper Closed Afte

Academic rigour, journalistic flair Subscribe Fourth estate follies Trawling through the dustbins of the UK media New Day barely dawned: here’s why UK’s latest paper closed after just two months May 5, 2016 12.39pm BST Author John Jewell Director of Undergraduate Studies, School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies, Cardiff University Launched with optimism, closed with regret. Anthony Devlin / PA Wire/Press Association Images So, barely two months – and 50 editions – since Trinity Mirror launched its bright new newspaper venture, The New Day, the company has announced its closure. Confirming widespread industry speculation – and the worst fears of the new paper’s staff – the company issued a trading statement saying: Although The New Day has received many supportive reviews and built a strong following on Facebook, the circulation for the title is below our expectations. As a result, we have decided to close the title on 6 May 2016. While disappointing, the launch and subsequent closure have provided new insights into enhancing our newspapers and a number of these opportunities will be considered over time. What an abrupt and sadly inevitable end to a project launched with great optimism and, whatever your views on the paper itself, a freshness of approach intended to challenge the cynicism and negativity of the conventional press. If you didn’t like newspapers – then this was the paper for you. The Guardian @guardian The New Day newspaper to shut only two months after launch The New Day newspaper to shut just two months after launch Publisher Trinity Mirror to announce closure of experimental national newspaper after sales fall to around 30,000 copies theguardian.com 9:16 PM · May 4, 2016 42 173 people are Tweeting about this The first (free) edition appeared on February 29 and as I wrote on this site it was vibrant, folksy, overwhelmingly upbeat and seemingly completely focused on a female audience.