Influence of Urbanisation and Plants on the Diversity and Abundance of Aphids and Their Ladybird and Hoverfly Predators in Dome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sequence Analysis of the Potato Aphid Macrosiphum Euphorbiae Transcriptome Identified Two New Viruses Marcella A

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Biology, Chemistry, and Environmental Sciences Science and Technology Faculty Articles and Faculty Articles and Research Research 3-29-2018 Sequence Analysis of the Potato Aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae Transcriptome Identified Two New Viruses Marcella A. Texeira University of California, Riverside Noa Sela Volcani Center, Bet Dagan, Israel Hagop S. Atamian Chapman University, [email protected] Ergude Bao University of California, Riverside Rita Chaudhury University of California, Riverside See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/sees_articles Part of the Agricultural Science Commons, Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, Biosecurity Commons, Entomology Commons, Parasitology Commons, and the Virus Diseases Commons Recommended Citation Teixeira MA, Sela N, Atamian HS, Bao E, Chaudhary R, MacWilliams J, et al. (2018) Sequence analysis of the potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae transcriptome identified two new viruses. PLoS ONE 13(3): e0193239. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0193239 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Science and Technology Faculty Articles and Research at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology, Chemistry, and Environmental Sciences Faculty Articles and Research by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sequence Analysis of the Potato Aphid Macrosiphum -

Effects of Cultural Methods for Controlling Aphids on Potatoes in Northeastern Maine

EFFECTS OF CULTURAL METHODS FOR CONTROLLING APHIDS ON POTATOES IN NORTHEASTERN MAINE W. A. Shands, Geddes W. Simpson and H. J. Murphy A Cooperative Publication of the Life Sciences and Agriculture Experiment Station, University of Maine at Orono, and the Entomology Research Division, Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture Technical Bulletin 57 June, 1972 Contents Acknowledgment Introduction Materials and Methods Varieties, plot size and separations, and cultural practices 4 Cultural treatments 5 Experimental design . 5 Leaf roll reservoir abundance . 5 Determination of disease spread 6 Prevalence and severity of Rhizoctonia .6 Yield of tubers 6 Abundance of aphids . 6 Expression of aphid abundance 7 Results and Discussion Effects of cultural treatments upon aphid populations . 8 Variations in total-season and relative abundance 8 Aphid populations in 1954 8 Aphid populations in 1955 .13 Aphid populations in 1956 .16 Aphid populations in 1957 17 Aphid populations in 1958 .21 Effects of cultural treatments upon yield of tubers 23 Effects of cultural treatments upon plant diseases 24 Spread of leaf roll 24 Prevalence and severity of Rhizoctonia 24 Summary and Conclusions .26 Acknowledgment We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Corinne C. Gordon, Biological Technician, Entomology Research Division, Agricultural Research Service, USDA, Orono, Maine 04473, who made the graphs, and aided in summarizing the data; and of Donald Merriam, Technician, Life Sciences and Agriculture Experiment Station, Aroostook Farm, Presque Isle, Maine 04769, and F. E. Manzer, Professor of Plant Pathology, University of Maine, Orono, Maine 04473, who made the field readings of leaf roll. Effects of Cultural Methods for Controlling Aphids1 on Potatoes in Northeastern Maine W.A. -

Environmental Factors Affecting Longevity, Adaptability and Diapause Termination of Exochomus Quadripustulatus L

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 45(2), pp. 377-385, 2013 Environmental Factors Affecting Longevity, Adaptability and Diapause Termination of Exochomus quadripustulatus L. (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae): A Predator of Lepidosaphes ulmi L. (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) on Apple Khawaja Farooq-Ahmad COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Abbottabad, Pakistan Abstract.- Adults Exochomus quadripustulatus L. were utilized to determine the effect of various environmental factors (mainly temperature) on the longevity, adaptability (hysteresis) and diapause termination either under controlled laboratory conditions or field insectary conditions. Newly eclosed male and female adults E. quadripustulatus from previously field collected pupae were studied for the lifespan of adults under different constant temperatures (15° and 20°C) and naturally fluctuating (ambient) temperatures using starved (no food), liquid diets (water, and 10% honey solution) and natural prey (mussel scale Lepidosaphes ulmi L.) on apple. Access to distilled water compared to starvation did not increase the longevity of adult but significantly prolonged the life span when honey solution was provided. Longevity in constant conditions and ambient depended on both temperature and food. Coccinellid E. quadripustulatus survived longer time (≥10 months) under field conditions on natural prey L. ulmi than under constant temperature (≤4 months). Prey L. ulmi was the best food for survival than 10% honey solution. The degree of adaptability (hysteresis) of adult E. quadripustulatus at alternating temperature regimes (ascending and descending) showed significant differences in feeding at decreasing temperature than increasing ones. The results indicate that, in natural conditions, the adult beetles may be well adapted if they are introduced to different climatic regions where it has not yet been tested. -

2U11/13482U Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date Λ ft / ft 3 November 2011 (03.11.2011) 2U11/13482U Al (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, A 47/06 (2006.01) A01P 7/04 (2006.01) CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (21) International Application Number: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, PCT/EP201 1/056129 KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (22) International Filing Date: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 18 April 201 1 (18.04.201 1) NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, (25) Filing Language: English TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (26) Publication Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 1016 1124.2 27 April 2010 (27.04.2010) EP GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): SYN- TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, GENTA PARTICIPATIONS AG [CH/CH]; EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, Schwarzwaldallee 215, CH-4058 Basel (CH). -

Paecilomyces Niveus Stolk & Samson, 1971 (Ascomycota

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.08014 Original Article Paecilomyces niveus Stolk & Samson, 1971 (Ascomycota: Thermoascaceae) as a pathogen of Nasonovia ribisnigri (Mosley, 1841) (Hemiptera, Aphididae) in Brazil M. A. C. Zawadneaka*, I. C. Pimentelb, D. Roblb, P. Dalzotob, V. Vicenteb, D. R. Sosa-Gómezc, M. Porsanib and F. L. Cuqueld aLaboratório de Entomologia Prof. Ângelo Moreira da Costa Lima, Departamento de Patologia Básica, Universidade Federal do Paraná – UFPR, CP 19020, CEP 81531-980, Curitiba, PR, Brazil bLaboratório de Microbiologia, Departamento de Patologia Básica, Universidade Federal do Paraná – UFPR, CP 19020, CEP 81531-980, Curitiba, PR, Brazil cLaboratório de Entomologia, Embrapa Soja, CP 231, CEP 86001-970, Londrina, PR, Brazil dDepartamento de Fitotecnia e Fitossanitarismo, Universidade Federal do Paraná – UFPR, Rua dos Funcionários, CP 1540, CEP 80035-050, Curitiba, PR, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: May 2, 2014 – Accepted: August 27, 2014 – Distributed: November 30, 2015 (With 2 figures) Abstract Nasonovia ribisnigri is a key pest of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) in Brazil that requires alternative control methods to synthetic pesticides. We report, for the first time, the occurrence of Paecilomyces niveus as an entomopathogen of the aphid Nasonovia ribisnigri in Pinhais, Paraná, Brazil. Samples of mummified aphids were collected from lettuce crops. The fungus P. niveus (PaePR) was isolated from the insect bodies and identified by macro and micromorphology. The species was confirmed by sequencing Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) rDNA. We obtained a sequence of 528 bp (accession number HQ441751), which aligned with Byssochlamys nivea strains (100% identities). In a bioassay, 120 h after inoculation of N. -

Anthecological Relations Reputedly Anemophilous Flowers and Syrphid

Ada Bot. Neerl. 25(3). June 1976, p. 205-211. Anthecological relations between reputedly anemophilous flowers and syrphid flies. II. Plantago media L. H. Leereveld A.D.J. Meeuse and P. Stelleman Hugo de Vries-laboratorium. Universiteit van Amsterdam SUMMARY After intensive field work in Upper Hessia (W. Germany) the authors have come to the con- clusion that although Plantago media L. is most probably visited much more frequently and wider of insects than P. lanceolata L.. flies of the by a range syrphid Melanostoma-Platychei- transfer rus group play a negligible role in the pollen of P. media. The possible reason for this unexpectedresult is anything but clear and only a tentative possibility is suggested. 1. INTRODUCTION After the relation between syrphid flies ofthe Melanostoma-Platycheirus (M P) been group and Plantago lanceolatahad studied in the Netherlands (Stelleman ofthis the role ofthese flies effective & Meeuse. part I series), possible syrphid as pollinators of other species of Plantago seemed a promising field of study. In the media, which to human to be particular species P. our senses appears more attractive than P. lanceolataboth optically and olfactorally, seemed a suitable p. object, the more so since a great many insect visitors have been recorded on media (see Knuth 1899and Kugler 1970). The opportunity arose when Professor Neubauerand Professor Weberling of the botanical institute of the University of Giessen invited us to study the pol- lination ecology of this species in the Giessen area. We arrived in the area when the flowering period of P. media had not reached its peak and stayed until in had been for some sites flowering was over or the grass mowed hay-making and the flowering spikes were cut off. -

Natural Enemies of the Currant Lettuce Aphid, Nasonovia Ribisnigri (Mosely) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and Their Population Fluctuations in Ahvaz, Iran

J. Crop Prot. 2014, 3 (4):487-497_______________________________________________________ Research Article Natural enemies of the currant lettuce aphid, Nasonovia ribisnigri (Mosely) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and their population fluctuations in Ahvaz, Iran Afrooz Farsi1*, Farhan Kocheili1, Mohammad Saeed Mossadegh1, Arash Rasekh1 and Mehrzad Tavoosi2 1. Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran. 2. Agriculture and Natural Resources Research Center of Khuzestan-Ahvaz. Abstract: Nasonovia ribisnigri (Mosely) is one of the most important pests of the lettuce plant and it was reported for the first time in Ahvaz in 2008. In order to investigate the dominant species of its natural enemies and their population fluctuations, sample were taken arbitrarily from fifty plants twice a week during the growing season in 2010-2012. In this study, ten species of predators, three species of parasitoids and two species of hyperparasitoids were collected and identified. Hoverflies with a relative frequency of 55% were the dominant predators. Peaks of lacewings and subsequently ladybird beetles were more coincident with peaks of aphid population in mid-March in the first year of studies. But their densities in the second year were very low. Also, hoverflies and parasitoids were mainly observed in the high densities in late March-early April, in both years. Regression analysis indicated that populations of aphids were mainly affected by ladybird beetles and lacewings in the first year of study, as well as by ladybird beetles, hoverflies and parasitoids in the second year. Therefore, additional studies are required for further evaluation on the potential abilities of these natural enemies being a good candidates for the future biological control programs. -

Aphis Spiraecola

Rapid Pest Risk Analysis (PRA) for Aphis spiraecola STAGE 1: INITIATION 1. What is the name of the pest? Aphis spiraecola Patch (Hemiptera, Aphididae) – Spiraea aphid (also Green citrus aphid). Synonyms: many, due to historic confusion over its identity; most common is Aphis citricola van der Goot (see CABI, 2013). 2. What initiated this rapid PRA? The UK Plant Health Risk Register identified the need to update the first UK PRA (MacLeod, 2000), taking into account recent information on hosts, impacts, vectored pathogens and UK status. 3. What is the PRA area? The PRA area is the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. STAGE 2: RISK ASSESSMENT 4. What is the pest’s status in the EC Plant Health Directive (Council Directive 2000/29/EC1) and in the lists of EPPO2? Aphis spiraecola is not listed in the EC Plant Health Directive, not recommended for regulation as a quarantine pest by EPPO and it is not on the EPPO Alert List. 5. What is the pest’s current geographical distribution? Aphis spiraecola probably originates in the Far East. It is now very widespread around the world in temperate and tropical regions, occurring across every continent except Antarctica (CABI, 2013). In Europe, A. spiraecola is found around the Mediterranean, with a patchy Balkan distribution and it is absent from Scandinavia and the Baltic states. It is stated as present in: Spain, Portugal, France, Switzerland, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Greece, Cyprus, Malta, and Russia (west of the Urals) (CABI 2013). It is not confirmed as being established in the Netherlands, either outdoors or under protection. -

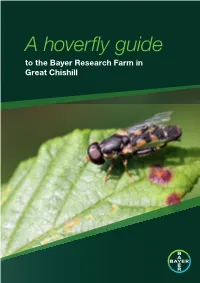

A Hoverfly Guide to the Bayer Research Farm in Great Chishill

A hoverfly guide to the Bayer Research Farm in Great Chishill 1 Orchard Farm, Great Chishill • Nesting and visiting birds ayer Crop Science’s farm in • Butterflies and moths Encouraging Hoverflies Great Chishill covers some 20 • Bees Bhectares on a gently undulating • Successful fledging of barn owl 1. Food Sources Hoverflies do not have suitable clay plateau to the south west of chicks (as an indicator of small Growing just about any wildflowers will mouthparts to feed from pea-flowers Cambridge, on the Hertfordshire mammal populations) attract at least some hoverflies and a such as clover, lucerne or sainfoin border. It is a working farm set up variety of species selected to flower that favour bees but will feed from to help the company research and Hoverflies continuously throughout the spring mints, both cornmint and watermint understand better, new crop protection Hoverflies are a group of Diptera (flies) and summer would be preferable. and other Labiates such as thyme, products and new seed varieties. As comprising the family Syrphidae with Traditional wildflower meadows are marjoram and so on. Some Crucifers its name implies, the farm used to be many being fairly large and colourful. often good places to look for hoverflies, are good such as the spring flowering an orchard and indeed, there remains Some of them, such as the Marmalade and there are several plants which cuckoo flower and hedge mustard; some apple and pear trees on the Hoverfly are generally common and are favoured. Common bramble is a later on water cress, oil seed rape and site used for testing of novel crop numerous enough to have a common magnet for various hoverflies and other other mustards are good. -

Aphid Species (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Infesting Medicinal and Aromatic Plants in the Poonch Division of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan

Amin et al., The Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences, 27(4): 2017, Page:The J.1377 Anim.-1385 Plant Sci. 27(4):2017 ISSN: 1018-7081 APHID SPECIES (HEMIPTERA: APHIDIDAE) INFESTING MEDICINAL AND AROMATIC PLANTS IN THE POONCH DIVISION OF AZAD JAMMU AND KASHMIR, PAKISTAN M. Amin1, K. Mahmood1 and I. Bodlah 2 1 Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Entomology, University of Poonch, 12350 Rawalakot, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan 2Department of Entomology, PMAS-Arid Agriculture University, 46000 Rawalpindi, Pakistan Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study conducted during 2015-2016 presents first systematic account of the aphids infesting therapeutic herbs used to cure human and veterinary ailments in the Poonch Division of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. In total 20 aphid species, representing 12 genera, were found infesting 35 medicinal and aromatic plant species under 31 genera encompassing 19 families. Aphis gossypii with 17 host plant species was the most polyphagous species followed by Myzus persicae and Aphis fabae that infested 15 and 12 host plant species respectively. Twenty-two host plant species had multiple aphid species infestation. Sonchus asper was infested by eight aphid species and was followed by Tagetes minuta, Galinosoga perviflora and Chenopodium album that were infested by 7, 6 and 5 aphid species respectively. Asteraceae with 11 host plant species under 10 genera, carrying 13 aphid species under 8 genera was the most aphid- prone plant family. A preliminary systematic checklist of studied aphids and list of host plant species are provided. Key words: Aphids, Medicinal/Aromatic plants, checklist, Poonch, Kashmir, Pakistan. -

HOVERFLY NEWSLETTER Dipterists

HOVERFLY NUMBER 41 NEWSLETTER SPRING 2006 Dipterists Forum ISSN 1358-5029 As a new season begins, no doubt we are all hoping for a more productive recording year than we have had in the last three or so. Despite the frustration of recent seasons it is clear that national and international study of hoverflies is in good health, as witnessed by the success of the Leiden symposium and the Recording Scheme’s report (though the conundrum of the decline in UK records of difficult species is mystifying). New readers may wonder why the list of literature references from page 15 onwards covers publications for the year 2000 only. The reason for this is that for several issues nobody was available to compile these lists. Roger Morris kindly agreed to take on this task and to catch up for the missing years. Each newsletter for the present will include a list covering one complete year of the backlog, and since there are two newsletters per year the backlog will gradually be eliminated. Once again I thank all contributors and I welcome articles for future newsletters; these may be sent as email attachments, typed hard copy, manuscript or even dictated by phone, if you wish. Please do not forget the “Interesting Recent Records” feature, which is rather sparse in this issue. Copy for Hoverfly Newsletter No. 42 (which is expected to be issued with the Autumn 2006 Dipterists Forum Bulletin) should be sent to me: David Iliff, Green Willows, Station Road, Woodmancote, Cheltenham, Glos, GL52 9HN, (telephone 01242 674398), email: [email protected], to reach me by 20 June 2006. -

Flower Visitation by Hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae)

A peer-reviewed version of this preprint was published in PeerJ on 3 December 2018. View the peer-reviewed version (peerj.com/articles/6025), which is the preferred citable publication unless you specifically need to cite this preprint. Klecka J, Hadrava J, Biella P, Akter A. 2018. Flower visitation by hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) in a temperate plant-pollinator network. PeerJ 6:e6025 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6025 Flower visitation by hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) in a temperate plant-pollinator network Jan Klecka1, Jir´ıHadravaˇ 1,2, Paolo Biella1,3, and Asma Akter1,3 1Czech Academy of Sciences, Biology Centre, Institute of Entomology, Ceskˇ e´ Budejovice,ˇ Czech Republic 2Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 3Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Ceskˇ e´ Budejovice,ˇ Czech Republic Corresponding author: Jan Klecka Email address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) are among the most important pollinators, although they attract less attention than bees. They are usually thought to be rather opportunistic flower visitors, although pre- vious studied demonstrated that they show colour preferences and their nectar feeding is affected by morphological constraints related to flower morphology. Despite the growing appreciation of hoverflies and other non-bee insects as pollinators, there is a lack of community-wide studies of flower visitation by syrphids. The aim of this paper is to provide a detailed analysis of flower visitation patterns in a species rich community of syrphids in a Central European grassland and to evaluate how species traits shape the structure of the plant-hoverfly flower visitation network.