Stutton Local History Journal No 31 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Solar BRANTHAM COURT 8 BRANTHAM 8 SUFFOLK

The Solar BRANTHAM COURT 8 BRANTHAM 8 SUFFOLK The Solar Distances Brantham Court, Brantham, Suffolk Manningtree: 3 miles Ipswich: 8 miles Colchester: 12 miles STUNNING PRINCIPAL RESIDENCE OF BRANTHAM COURT London’s Liverpool Street Station from 55, 65 and 50 minutes respectively WITH MATURE GARDENS & OUTSTANDING RIVER VIEWS (All mileages and times are approximate) Accommodation Summary • 7/8 bedrooms, 4 bath/shower rooms, reception hall, 3 reception rooms • Solar, kitchen/breakfast room, laundry room, 2 cloakrooms, pantry • Private lawned gardens, double garage, parking for 4 cars • Mature communal gardens including swimming pool • Private garden of 1.15 acres and communal gardens of 6 acres. Situation Situated on the edge of the village, Brantham Court is in a rural yet easily accessible position. It is within easy reach of the centre of Manningtree which lies at the head of the Stour Estuary and is situated between Colchester, Ipswich and Harwich. It offers a wide variety of amenities including a sailing and yacht club, various pubs and restaurants, general stores, optician, doctors surgery, primary and secondary school, delicatessen, banks and sports centre. There are intercity commuter trains from the main line station direct to London’s Liverpool Street, taking approximately 55 minutes. The villages of Dedham and East Bergholt are just a few minutes drive. The nearby towns of Colchester, reputed to be the oldest recorded Roman town in Britain, and Ipswich, Suffolk’s county town also offer main line rail links as well as a wider range of shopping, educational and recreational facilities. There are regular ferry services to the continent from Harwich Description The Solar forms the principal section of Brantham Court, a Neo-Elizabethan mansion constructed around 1850 and enlarged in 1913 from brick under pitched tiled roofs. -

January 2019

Box River News January 2019 Boxford • Edwardstone • Groton • Little Waldingfield • Newton Green Vol 19 No 1 A Very Merry Christmas and a Happy and Healthy New Year to you all Nanny Nora (David Phillips) and Favor (Margaret Clapp) Photo Trudi Wild GRAND CHRISTMAS FAIR GROTON’S CHEESE AND WINE PARTY Groton’s Cheese & Wine – Thanks to everyone who attended the Cheese & Wine Party. It was a very happy and fun event and I would like to thank Sheila & her helpers for the wonderful food, Anthea for manning the gift stall, Val for a well stocked Bar, Lisa for organising the Secret Santa, Stephen W. for all his help, all those who brought raffle prizes and Bob for being Master of Ceremonies. A grand total of £730.00 was raised for Church Funds. Thank you All. Happy Christmas and New Year. The Grand Christmas Fair held in Boxford Village Hall on Friday 7th Our next fundraising event is the Quiz & Chips evening (with Quiz Master Peter) on 18th January 2019. Jayne Foster. December raised £600 For the Village Hall funds. Photoʼs David Lamming Friday 11 January 8 £20.00. TONY KOFI AND THE ORGANISATION: ‘POINT BLANK ʻA killer band with real biteʼ JAZZWISE Tony Kofi BARITONE SAXOPHONE Pete Whittaker ORGAN Simon Fersby GUITAR Pete Cater DRUMSl Friday 28 December 8 £25.00. Friday 18 January 8 £18.00. Sax Appeal NIGEL PRICE QUARTET Sax Appeal – showcasing saxophone and sax players, blowing ʻLovers of jazz across the UK –prepare to be taken by stormʼ THE away cobwebs and having so much fun for (try to believe this) over JAZZ MANN 40 years! The perfect late Christmas gift to yourself. -

The Felixstowe Society Newsletter

THE FELIXSTOWE SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Issue No. 115 May 2017 Registered Charity No. 27744 To accompany this issue: A special booklet to follow up on the Bala Cottage issue. Can You Help? Please read Page 6 to find out. 1 The Felixstowe Society is established for the public benefit of people who either live or work in Felixstowe and Walton. Members are also welcome from The Trimleys and the surrounding villages. The Society endeavours to: stimulate public interest in these areas promote high standards of planning and architecture and secure the improvement, protection, development and preservation of the local environment. Cover photo: On the left - Gulpher Pond. Lower right - The Grove Contents 3 Notes from the Chairman 4 Calendar - May to December 5 Society News 7 Speaker Evening - Richard Harvey 8 Speaker Evening - Sister Marian 9 Visit to the Port of Felixstowe 10 Speaker Evening - Nigel Pickover 11 Beach Clean 12 The Felixstowe Walkers 13 The Society Members’ Feature - Michael and Penny Thomas 16 The Beach Hut and Chalet Owners 18 News from Felixstowe Museum 19 Research Corner 27 Part 3 - Bowls in Felixstowe 21 Felixstowe Community Hospital League of Friends 23 Thomas Cotman and Charles Emeny 25 Planning Applications - January to March 2017 26 Listed Buildings in Felixstowe and Walton 28 Photo Quiz Contacts: Roger Baker - Chairman until the AGM - 01394 282526 Hilary Eaton - Treasurer - 01394 549321 2 Notes from the Chairman These are my final “Notes” as Chairman of The Society. You might remember that I resigned on a previous occasion at the end of 2015 when Phil Hadwen was due to take over from me. -

Babergh Development Framework to 2031

Summary Document Babergh Development Framework to 2031 Core Strategy Growth Consultation Summer 2010 Babergh Development Framework to 2031 Core Strategy Consultation – Future Growth of Babergh District to 2031 i. Babergh is continuing its work to plan ahead for the district’s long-term future and the first step in this will be the ‘Core Strategy’ part of the Babergh Development Framework (BDF). It is considered that as a starting point for a new Plan, the parameters of future change, development and growth need to be established. ii. It is important to plan for growth and further development to meet future needs of the district, particularly as the Core Strategy will be a long term planning framework. Key questions considered here are growth requirements, the level of housing growth and economic growth to plan for and an outline strategy for how to deliver these. iii. Until recently, future growth targets, particularly those for housing growth, were prescribed in regional level Plans. As these Plans have now been scrapped, there are no given growth targets to use and it is necessary to decide these locally. In planning for the district’s future, a useful sub-division of Babergh can be identified. This is to be used in the BDF and it includes the following 3 main areas: Sudbury / Great Cornard - Western Babergh Hadleigh / Mid Babergh Ipswich Fringe - East Babergh including Shotley peninsula 1. Employment growth in Babergh – determining the scale of growth in employment; plus town centres and tourism 1.1 Babergh is an economically diverse area, with industrial areas at the Ipswich fringe, Sudbury, Hadleigh and Brantham (and other rural areas); traditional retail sectors in the two towns; a high proportion of small businesses; and tourism / leisure based around historic towns / villages and high quality countryside and river estuaries. -

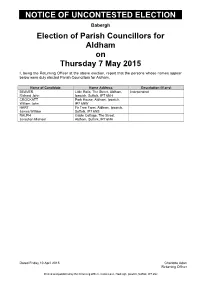

Notice of Uncontested Election

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Aldham on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aldham. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BEAVER Little Rolls, The Street, Aldham, Independent Richard John Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6NH CROCKATT Park House, Aldham, Ipswich, William John IP7 6NW HART Fir Tree Farm, Aldham, Ipswich, James William Suffolk, IP7 6NS RALPH Gable Cottage, The Street, Jonathan Michael Aldham, Suffolk, IP7 6NH Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Alpheton on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Alpheton. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ARISS Green Apple, Old Bury Road, Alan George Alpheton, Sudbury, CO10 9BT BARRACLOUGH High croft, Old Bury Road, Richard Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BT KEMP Tresco, New Road, Long Melford, Independent Richard Edward Suffolk, CO10 9JY LANKESTER Meadow View Cottage, Bridge Maureen Street, Alpheton, Suffolk, CO10 9BG MASKELL Tye Farm, Alpheton, Sudbury, Graham Ellis Suffolk, CO10 9BL RIX Clapstile Farm, Alpheton, Farmer Trevor William Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BN WATKINS 3 The Glebe, Old Bury Road, Ken Alpheton, Sudbury, Suffolk, CO10 9BS Dated Friday 10 April 2015 Charlotte Adan Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Corks Lane, Hadleigh, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP7 6SJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Babergh Election of Parish Councillors for Assington on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Assington. -

Boxford-Appeal-Decision-(2).Pdf

Appeal Decision Inquiry held on 21-24 August 2018 Site visit made on 24 August 2018 by Simon Warder MA BSc(Hons) DipUD(Dist) MRTPI an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State Decision date: 30th October 2018 Appeal Ref: APP/D3505/W/18/3197391 Land off Daking Avenue, Boxford CO10 5AA The appeal is made under section 78 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 against a refusal to grant outline planning permission. The appeal is made by Landex Ltd (Mr Dan Davies) against the decision of Babergh District Council. The application Ref B/17/00091, received by the Council on 23 January 2017, was refused by notice dated 13 November 2017. The development proposed is up to 24 dwellings (including up to 8 affordable dwellings) with access. Decision 1. The appeal is dismissed. Preliminary Matters 2. The application reserves all matters except access for further approval. However, the application was supported by a Proposed Block Plan (drawing number 4862 SK03 Rev E) which shows the layout of the access roads, buildings, open space and landscaping. A revised version of this plan (drawing number 4862 SK03 Rev E-1), indicating the route of an access to Woodland Trust land to the south of the appeal site, was submitted at the Inquiry. The appellant also confirmed at the Inquiry that approval was sought for the point of access only and that other elements shown on the Proposed Block Plan are indicative only. I have considered the revised plan on that basis. 3. At the time that the parties’ statements of case were submitted the Council accepted that it could not demonstrate a five year supply of housing land. -

Notice of Poll Babergh

Suffolk County Council ELECTION OF COUNTY COUNCILLOR FOR THE BELSTEAD BROOK DIVISION NOTICE OF POLL NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT :- 1. A Poll for the Election of a COUNTY COUNCILLOR for the above named County Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00am and 10:00pm. 2. The number of COUNTY COUNCILLORS to be elected for the County Division is 1. 3. The names, in alphabetical order and other particulars of the candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of the persons signing the nomination papers are as follows:- SURNAME OTHER NAMES IN HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE FULL NOMINATION PAPERS 16 Two Acres Capel St. Mary Frances Blanchette, Lee BUSBY DAVID MICHAEL Liberal Democrats Ipswich IP9 2XP Gifkins CHRISTOPHER Address in the East Suffolk The Conservative Zachary John Norman, Nathan HUDSON GERARD District Party Candidate Callum Wilson 1-2 Bourne Cottages Bourne Hill WADE KEITH RAYMOND Labour Party Tom Loader, Fiona Loader Wherstead Ipswich IP2 8NH 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows:- POLLING POLLING STATION DESCRIPTIONS OF PERSONS DISTRICT ENTITLED TO VOTE THEREAT BBEL Belstead Village Hall Grove Hill Belstead IP8 3LU 1.000-184.000 BBST Burstall Village Hall The Street Burstall IP8 3DY 1.000-187.000 BCHA Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-152.000 BCOP Copdock & Washbrook Village Hall London Road Copdock & Washbrook Ipswich IP8 3JN 1.000-915.500 BHIN Hintlesham Community Hall Timperleys Hintlesham IP8 3PS 1.000-531.000 BPNN Holiday Inn Ipswich London Road Ipswich IP2 0UA 1.000-2351.000 BPNS Pinewood - Belstead Brook Muthu Hotel Belstead Road Ipswich IP2 9HB 1.000-923.000 BSPR Sproughton - Tithe Barn Lower Street Sproughton IP8 3AA 1.000-1160.000 BWHE Wherstead Village Hall Off The Street Wherstead IP9 2AH 1.000-244.000 5. -

2A 2 93 92 9497 98

Babergh and Essex Services 2 2A 92 93 94 97 98 695 Your guide to our bus services from Ipswich into Babergh, Essex & Tendering Bus times from Sunday 29th August 2021 2/2A Clacton | Clacton Shopping Village | Weeley | Tendring | Manningtree | Mistley Mondays to Saturdays Service Number 2A ◆ 2◆ 2◆ 2◆ 2A ◆ 2◆ Clacton, Pier Avenue 0625 0830 1055 1300 1525 1735 Clacton, Rail Station 0627 0832 1057 1302 1527 1737 Clacton, Valley Road, The Range 0632 0837 1102 1307 1532 1742 Clacton, Shopping Village 0639 0844 1109 1314 1539 1749 Clacton, Lt Clacton Morrisons 0641 0846 1111 1316 1541 1751 Little Clacton, Blacksmiths Arms 0645 0850 1115 1320 1545 1755 2 Weeley, The Street 0651 0856 1121 1326 1551 1801 Tendring Heath, Hall Lane 0658 0903 1128 1333 1558 1808 Little Bentley, Bricklayers Arms — 0908 1133 1338 — 1813 Little Bromley, Post Office — 0918 1143 1348 — 1823 Lawford, Place — 0921 1146 1351 — 1826 Manningtree Rail Station — 0925 1150 1355 — 1830 Manningtree, High School — 0930 1155 1400 — 1835 Mistley Church — 0933 1158 1403 — 1838 Horsley Cross, Cross Inn 0702 — — — 1602 — Mistley Heath 0710 — — — 1610 — Mistley, Rigby Avenue 0713 0935 1200 1405 1613 1840 Code: ◆ - This journey is sponsored by Essex County Council No service on Sundays or Bank Holidays 2/2A Mistley | Manningtree | Tendring | Weeley | Clacton Shopping Village | Clacton Mondays to Saturdays Service Number 2◆ 2◆ 2A ◆ 2◆ 2◆ 2◆ Mistley, Rigby Avenue 0715 0940 1202 1410 1615 1845 Mistley Heath — — 1205 — — — Horsley Cross, Cross Inn — — 1213 — — — Mistley, Church 0718 0943 — 1413 -

Appendix 2: Supply Analysis Method and Matrix

Haven Gateway Partnership Suffolk Haven Gateway Employment Land Review & Strategic Sites Study Appendix 2: Supply Analysis Method and Matrix October 2009 www.gvagrimley.co.uk Haven Gateway Partnership Suffolk Haven Gateway Employment Land Review Contents 1. EMPLOYMENT LAND SUPPLY ANALYSIS ........................................................... 1 September 2009 Haven Gateway Partnership Suffolk Haven Gateway Employment Land Review 1. EMPLOYMENT LAND SUPPLY ANALYSIS METHOD 1.1 To fully explain the results and conclusions presented within the report it is necessary to outline the method used in detail. This ultimately informs the conclusions and recommendations that are detailed in the main body of the report. Employment Land Supply Analysis 1.2 This section in each local authority chapter presents the findings of the analysis of the supply of employment land in each District / Borough. It is based on field surveys carried out by the respective local authorities and GVA Grimley with the work undertaken between January and May 2009. The surveys undertaken were an audit of the allocated employment sites in the adopted Local Plans across the three local authority areas comprising the Suffolk Haven Gateway including the analysis of the following variables: • Sustainability (including public transport accessibility and adjacent uses) – By Local Authority • Local Access (including strategic road access and internal environment) – By Local Authority • Market Factors (including local access and commercial viability) – By Local Authority / GVA Grimley 1.3 Together these provide a “snapshot” of current employment land conditions within the respective local authority areas to allow an assessment of the current provisions fitness for purpose to satisfy employment land requirements through the LDF process. -

Stutton Local History Journal No 30 2014

Stutton Local History Journal No 30 2014 1 Editor’s preface Welcome to the Local History Journal for 2014. It has been enormous fun drawing together the material for this issue, not least because so many of the articles have not been static but have had additions and refinings as more information became available to the authors. Of course, that is part of the joy of local history research or indeed any research: the task is never completed and even the facts unearthed can be viewed in all sorts of ways, depending on how you present them, tweak them, emphasise them and your underlying purpose in presenting them. A topical issue is of course this year about just how the first of the major world wars started. A major part of this journal features items to do with WW1 and we have more in the pipeline to tease out over the next 4 years. Mary Boyton has taken on a gargantuan task of retyping the journal that she introduces on page 2 and this will be uploaded onto our website over the next few months. Do please look at it from time to time. You can be sure that others are, from knowledge of the queries we receive from the general public. Our grateful thanks must go out to the late Greta Gladwell for donating such interesting material to the village. Do you have anything lurking in your attic or under the bed? Nigel Banham has used and developed the research that Chris Moss undertook for the flying field in Stutton, and has also helped those of us who aren’t experts in any sort of planes, never mind WW1 fighter planes, to understand the intricacies of their development. -

Special Qualities of the Dedham Vale AONB Evaluation of Area Between Bures and Sudbury

Special Qualities of the Dedham Vale AONB Evaluation of Area Between Bures and Sudbury Final Report July 2016 Alison Farmer Associates 29 Montague Road Cambridge CB4 1BU 01223 461444 [email protected] In association with Julie Martin Associates and Countryscape 2 Contents 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Appointment............................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Background and Scope of Work.............................................................................. 3 1.3 Natural England Guidance on Assessing Landscapes for Designation ................... 5 1.4 Methodology and Approach to the Review .............................................................. 6 1.5 Format of Report ..................................................................................................... 7 2: The Evaluation Area ...................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Landscape Character Assessments as a Framework ............................................. 8 2.2 Defining and Reviewing the Evaluation Area Extent ................................................ 9 3: Designation History ..................................................................................................... 10 3.1 References to the Wider Stour Valley in the Designation of the AONB ................. 10 3.2 Countryside Commission Designation -

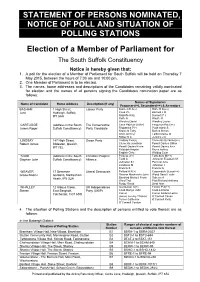

Statement of Persons Nominated & Notice of Poll & Situation of Polling

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED, NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Election of a Member of Parliament for The South Suffolk Constituency Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a Member of Parliament for South Suffolk will be held on Thursday 7 May 2015, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. One Member of Parliament is to be elected. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BASHAM 1 High Street, Labour Party Dunnett E A(+) Rolfe R D(++) Jane Hadleigh, Suffolk, Cook P F Barford J M IP7 5AH Ratcliffe Katy Dunnett P J Rolfe A Woulfe K Wordley David Wordley Louise CARTLIDGE (address in the South The Conservative Cave Patricia G M(+) Ferguson Paul(++) James Roger Suffolk Constituency) Party Candidate Fitzpatrick P H Pugh Alaric S Kramers Toby Barrett Simon Antill Jennifer Talbot Clarke D Ridley N A Jenkins J A LINDSAY 147 High Street, Green Party Lindsay Eva(+) Clements Suzanne(++) Robert James Bildeston, Ipswich, Clements Jonathan Powell Davies Gillian IP7 7EL Powell Davies Kevin Powell Davies Alex Biddulph Angela Bruce Ashley English Chloe Widdup Colin TODD (address in the South Christian Peoples Pickess J(+) Tuttlebury M(++) Stephen John Suffolk Constituency) Alliance Todd A Johnston Elizabeth M Johnston S L Percival Julie Landman M Johnston