New Forest Visitor Survey Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

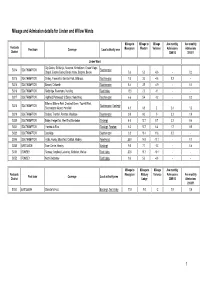

Mileage and Admissions

Mileage and Admission details for Linden and Willow Wards Mileage to Mileage to Mileage Ave monthly Ave monthly Postcode Post town Coverage Local authority area Moorgreen Western Variance Admissions Admissions District 2009/10 2010/11 Linden Ward City Centre, St. Mary's, Newtown, Nicholstown, Ocean Village, SO14 SOUTHAMPTON Southampton Chapel, Eastern Docks, Bevois Valley, Bargate, Bevois 5.6 5.0 -0.6 - 0.2 SO15 SOUTHAMPTON Shirley, Freemantle, Banister Park, Millbrook, Southampton 7.6 3.0 -4.6 0.2 - SO16 SOUTHAMPTON Bassett, Chilworth Southampton 8.4 3.5 -4.9 - 0.1 SO16 SOUTHAMPTON Redbridge, Rownhams, Nursling Test Valley 13.0 2.0 -11 - - SO17 SOUTHAMPTON Highfield, Portswood, St Denys, Swaythling Southampton 6.6 5.4 -1.2 - 0.2 Bitterne, Bitterne Park, Chartwell Green, Townhill Park, SO18 SOUTHAMPTON Southampton , Eastleigh Southampton Airport, Harefield 4.5 6.5 2 2.4 1.2 SO19 SOUTHAMPTON Sholing, Thornhill, Peartree, Woolston Southampton 9.0 9.0 0 3.2 1.9 SO30 SOUTHAMPTON Botley, Hedge End, West End, Bursledon Eastleigh 4.0 12.7 8.7 2.2 0.4 SO31 SOUTHAMPTON Hamble-le-Rice Eastleigh , Fareham 6.3 12.7 6.4 1.7 0.5 SO32 SOUTHAMPTON Curdridge Southampton 3.8 15.4 11.6 0.2 - SO45 SOUTHAMPTON Hythe, Fawley, Blackfield, Calshot, Hardley New Forest 25.9 14.8 -11.1 - 0.1 SO50 EASTLEIGH Town Centre, Hamley Eastleigh 9.0 7.7 -1.3 - 0.6 SO51 ROMSEY Romsey, Ampfield, Lockerley, Mottisfont, Wellow Test Valley 20.8 10.7 -10.1 - - SO52 ROMSEY North Baddesley Test Valley 9.6 5.0 -4.6 - - Mileage to Mileage to Mileage Ave monthly Postcode Moorgreen Melbury Variance Admissions Ave monthly Post town Coverage Local authority area District Lodge 2009/10 Admissions 2010/11 SO53 EASTLEIGH Chandler's Ford Eastleigh , Test Valley 11.0 9.0 -2 1.8 0.6 1 Mileage to Mileage to Mileage Ave monthly Ave monthly Postcode Post town Coverage Local authority area Moorgreen Western Variance Admissions Admissions District 2009/10 2010/11 Willow Ward City Centre, St. -

Fordingbridge Town Design Statement 1 1

The Fordingbridge Community Forum acknowledges with thanks the financial support provided by the New Forest District Council and Awards for All towards the production of this report which was designed and printed by Phillips Associates and James Byrne Printing Ltd. CONTENTS LIST ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As an important adjunct to the Fordingbridge 1 Introduction 2 Health Check, work began on a Town Design Statement for Fordingbridge in 2005. A revised 2 Historical context 3 remit resulted in a fresh attempt being made in 2007. To ensure that the ultimate statement would 3 Map of area covered by this Design Statement 5 be a document from the local community, an invi- tation was circulated to many organisations and 4 The Rural Areas surrounding the town 6 individuals inviting participation in the project. Nearly 50 people attended an initial meeting in 5 Street map of Fordingbridge and Ashford 1 9 January 2007, some of whom agreed to join work- ing parties to survey the area. Each working party 6 Map of Fordingbridge Conservation Area 10 wrote a detailed description of its section. These were subsequently combined and edited to form 7 Plan of important views 11 this document. 8 Fordingbridge Town Centre 12 The editors would like to acknowledge the work carried out by many local residents in surveying 9 The Urban Area of Fordingbridge outside the the area, writing the descriptions and taking pho- Town Centre 18 tographs. They are indebted also to the smaller number who attended several meetings to review, 10 Bickton 23 amend and agree the document’s various drafts. -

CCATCH – the Solent

!∀ #∃ % # !∀ #∃ % # &∋ # (( )∗(+,−( CCATCH – The Solent Evaluation of the Beaulieu to Calshot Pathfinder A report by Dr Anthony Gallagher and Alan Inder to Hampshire County Council February 2012 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides an analysis and evaluation of the CCATCH – Beaulieu to Calshot Pathfinder project; the aim being to draw out the lessons learned and areas of best practice so as to inform the wider CCATCH - the Solent project, as well as the Interreg IVa funded CC2150 and Beyond. The methods employed to gather data included interviewing the key stakeholders involved in the process as well as the engagement consultants who facilitated it. This was supplemented by carrying out a public survey to gauge the project awareness and to interview the project managers of several other coastal adaptation projects, so as to enable a comparison with the work being carried out elsewhere. The results are generally very supportive of the approach taken and the tools and techniques employed during the Pathfinder, though highlighting with some clear room for improvement and consideration. On the basis that the selection of the area and the need for the project has already been established, the lessons learned relate inter alia to the application of stakeholder engagement and the commitment to implement identifiable actions; where engagement relates to its use both at the outset of the project and as a part of a developed on-going network beyond the lifetime of the funding. Commitment to following through with specific actions identified as part of the Adaptation Plan could then be implemented. In order to agree the Plan, and identify actions, it was clear that there was a need for specialist skills, and that these had been available for the Pathfinder. -

The Test Valley (Electoral Changes) Order 2018

Draft Order laid before Parliament under section 59(9) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009; draft to lie for forty days pursuant to section 6(1) of the Statutory Instruments Act 1946, during which period either House of Parliament may resolve that the Order be not made. DRAFT STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2018 No. LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The Test Valley (Electoral Changes) Order 2018 Made - - - - *** Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) and (3) Under section 58(4) of the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009( a) (“the Act”), the Local Government Boundary Commission for England( b) (“the Commission”) published a report dated October 2017 stating its recommendations for changes to the electoral arrangements for the borough of Test Valley. The Commission has decided to give effect to those recommendations. A draft of the instrument has been laid before each House of Parliament, a period of forty days has expired since the day on which it was laid and neither House has resolved that the instrument be not made. The Commission makes the following Order in exercise of the power conferred by section 59(1) of the Act. Citation and commencement 1. —(1) This Order may be cited as the Test Valley (Electoral Changes) Order 2018. (2) This article and article 2 come into force on the day after the day on which this Order is made. (3) The remainder of this Order comes into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary, or relating, to the election of councillors, on the day after the day on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in England and Wales( c) in 2019. -

Archaeological Excavation and Watching Briefs at Ellingham Farm, Near Ringwood, Hampshire, 1988-1991

Proc Hampsh Field Club Archaeol Soc, Vol 51, 1995, 59-76 ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION AND WATCHING BRIEFS AT ELLINGHAM FARM, NEAR RINGWOOD, HAMPSHIRE, 1988-1991 By C A BUTTERWORTH with contributions by W BOISMIER, R MJ CLEAL, E L MORRIS andRH SEAGER-SMITH ABSTRACT runs through Field 1, to the east of which the ground is slightly higher, as it is in Field 4. An evaluation and series of watching briefs were carried out in advance of and during gravel extraction at Ellingham Farm, Blashford, Hampshire, between 1988 and 1991. Features ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ranging in date from Middle Bronze Age to Roman were investigated and finds dating from Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age to Saxon periods recovered from unslratified deposits. A Evidence of archaeological activity from early significant concentration of features dating to the Late Bronze prehistoric through to Saxon times has been Age/Early Iron Age and Roman periods was recorded at the recorded in the area around Ellingham and northern end of the site. Blashford, and the Avon valley as a whole is an area of high archaeological potential. The Hampshire County Sites and Monuments INTRODUCTION Record lists a series of previous discoveries in the immediate vicinity of the site. Palaeolithic and An archaeological evaluation of land at Neolithic flints have been found to the south and Ellingham Farm, Blashford, near Ringwood, was east of Ellingham Farm. A Bronze Age cremation commissioned by Tarmac Roadstone Ltd. in burial, axes, worked flints and pottery, together 1988, at the request of Hampshire County with Iron Age and Roman pottery have been Council, before the determination of a planning found approximately 250 m south of Ellingham application for gravel extraction. -

Peat Database Results Hampshire

Baker's Rithe, Hampshire Record ID 29 Authors Year Allen, M. and Gardiner, J. 2000 Location description Deposit location SU 6926 1041 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Preserved timbers (oak and yew) on peat ledge. One oak stump in situ. Peat layer 0.15-0.26 m deep [thick?]. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available -1 m OD Yes Notes 14C details ID 12 Laboratory code R-24993/2 Sample location Depth of sample Dated sample description [-1 m OD] Oak stump Age (uncal) Age (cal) Delta 13C 3735 ± 60 BP 2310-1950 cal. BC Notes Stump BB Bibliographic reference Allen, M. and Gardiner, J. 2000 'Our changing coast; a survey of the intertidal archaeology of Langstone Harbour, Hampshire', Hampshire CBA Research Report 12.4 Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 1 of 86 Bury Farm (Bury Marshes), Hampshire Record ID 641 Authors Year Long, A., Scaife, R. and Edwards, R. 2000 Location description Deposit location SU 3820 1140 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available Yes Notes 14C details ID 491 Laboratory code Beta-93195 Sample location Depth of sample Dated sample description SU 3820 1140 -0.16 to -0.11 m OD Transgressive contact. Age (uncal) Age (cal) Delta 13C 3080 ± 60 BP 3394-3083 cal. BP Notes Dark brown humified peat with some turfa. Bibliographic reference Long, A., Scaife, R. and Edwards, R. 2000 'Stratigraphic architecture, relative sea-level, and models of estuary development in southern England: new data from Southampton Water' in ' and estuarine environments: sedimentology, geomorphology and geoarchaeology', (ed.s) Pye, K. -

New Forest Wetland Management Plan 2006

LIFE 02 NAT/UK/8544 New Forest Wetland Management Plan Plate 1 Dry stream bed of Fletchers Brook - August 2005 3.18 LIFE 02 NAT/UK/8544 New Forest Wetland Management Plan Table 3-8: Flow Statistics Lymington Hampshire Avon (R. Lymington Tributaries at Brockenhurst) (Dockens Water) Catchment Size 98.9 km2 17.15 km2 Permeability Mixed permeability Low to Mixed permeability Mean Annual rainfall (1961-90) 854 mm 831 mm Elevation 8.4-117.7m - Mean flow 1.06 m3s-1 0.26 m3s-1 95% exceedance (Q95) 0.052 m3s-1 0.047 m3s-1 10% exceedance (Q10) 2.816 m3s-1 0.592 m3s-1 Source: Centre of Ecology & Hydrology 3.4.5 Flow patterns Flow patterns are characterised by glides (slow flowing water), riffles (medium flowing water) and runs (fast flowing water). Life 3 studies in the Blackwater and Highland Water sub-catchments found that glides tend be to the most common form of flow followed by riffles and runs. Pools (still water) are noticeably rare in modified reaches being replaced by glides or runs. Pools where they occur are usually found at meander bends apices. Cascades and small water falls also occur at the faces of debris dams. Channelisation tends to affect the flow type in that it reduces the number of pools. Dominant flow types for the Highland Water and Black Water are shown in Figure 10. It is probable that a similar pattern would be found in the other river catchments. 3.4.6 Bank & bed material Bank material is made up of clay, fines, sand and gravel. -

1 ITEM 4 – Table 1 Test Valley 2010/11 Capital Programme

ITEM 4 – Table 1 Test Valley 2010/11 Capital Programme Maintenance and Special Maintenance Schemes Special Maintenance Programme Location Ward Brief Details Status A343 Salisbury Broughton and Kerbing Complete Road, The Wallops Stockbridge A3057 Northern St. Mary’s Footway Reconstruction Complete Avenue, Andover A3090 Pauncefoot Romsey Extra Drainage Improvements December Hill, Romsey A3090 towards Romsey Extra Drainage Improvements Q4 Ower A3090 Winchester Abbey Footway Reconstruction Q4 Road, Romsey A3057 Southampton Romsey Extra Drainage Improvements Q4 Road, Romsey A 3057 Stockbridge Broughton and Drainage Improvements Q4 Road, Lexford Stockbridge A3057 Greatbridge Romsey Extra Carriageway Resurfacing Q3 Road, Romsey A3057 Enham Arch Roundabout, St Mary’s Carriageway Resurfacing December Andover A3057 Malmesbury Abbey Carriageway Resurfacing Q3 Road, Romsey 1 Chilworth, A3057 Romsey Nursling and Carriageway Resurfacing Q3 Road, Rownhams Rownhams A3057 Alma Road, Abbey Carriageway Resurfacing Q3 Romsey Various Various Tactile Crossings Ongoing Houghton Road, Broughton and Drainage Improvements Complete Houghton Stockbridge Roberts Road, Harewood Drainage Improvements Q4 Barton Stacey Bengers Lane, Dun Valley Drainage Improvements Complete Mottisfont Kimbridge Lane, Kings Somborne Carriageway Resurfacing Complete Kimbridge and Michelmersh Lockerley Road, Dun Valley Drainage Improvements Q4 Dunbridge Chilworth, Rownhams Way, Nursling and Footway Reconstruction Q3 Rownhams Rownhams Wellow Drove, West Blackwater Haunching Q4 Wellow Braishfield Road, Ampfield and Ampfield & Braishfield Q3 Braishfield Braishfield Camelot Close, Alamein Footway Reconstruction Q3 Andover Dean Road, West Dun Valley Footway & Kerbing Q3 Tytherley 2 Kinver Close, Great Cupernham Footway Reconstruction Q3 Woodley Penton Park Lane, Penton Bellinger Drainage Improvements Q3 Penton Mewsey Main Road, (No Harewood Footway Reconstruction Q4 Name) Barton Stacey Union Street and Georges Yard, St. -

Local Produce Guide

FREE GUIDE AND MAP 2019 Local Produce Guide Celebrating 15 years of helping you to find, buy and enjoy top local produce and craft. Introducing the New Forest’s own registered tartan! The Sign of True Local Produce newforestmarque.co.uk Hampshire Fare ‘‘DON’T MISS THIS inspiring a love of local for 28 years FABULOUS SHOW’’ MW, Chandlers Ford. THREE 30th, 31st July & 1st DAYS ONLY August 2019 ''SOMETHING FOR THE ''MEMBERS AREA IS WHOLE FAMILY'' A JOY TO BE IN'' PA, Christchurch AB, Winchester Keep up to date and hear all about the latest foodie news, events and competitions Book your tickets now and see what you've been missing across the whole of the county. www.hampshirefare.co.uk newforestshow.co.uk welcome! ? from the New Forest Marque team Thank you for supporting ‘The Sign of True Local Produce’ – and picking up your copy of the 2019 New Forest Marque Local Produce Guide. This year sees us celebrate our 15th anniversary, a great achievement for all involved since 2004. Originally formed as ‘Forest Friendly Farming’ the New Forest Marque was created to support Commoners and New Forest smallholders. Over the last 15 years we have evolved to become a wide reaching ? organisation. We are now incredibly proud to represent three distinct areas of New Forest business; Food and Drink, Hospitality and Retail and Craft, Art, Trees and Education. All are inherently intertwined in supporting our beautiful forest ecosystem, preserving rural skills and traditions and vital to the maintenance of a vibrant rural economy. Our members include farmers, growers and producers whose food and drink is grown, reared or caught in the New Forest or brewed and baked using locally sourced ingredients. -

Section 3: Site-Specific Proposals – Totton and the Waterside

New Forest District (outside the National Park) Local Plan Part 2: Sites and Development Management Adopted April 2014 Section 3: Site-specific Proposals – Totton and the Waterside 57 New Forest District (outside the National Park) Local Plan Part 2: Sites and Development Management Adopted April 2014 58 New Forest District (outside the National Park) Local Plan Part 2: Sites and Development Management Adopted April 2014 3.1 The site-specific policies in this section are set out settlement by settlement – broadly following the structure of Section 9 of the Core Strategy: Local implications of the Spatial Strategy. 3.2 The general policies set out in: • the Core Strategy, • National Planning Policy and • Development Management policies set out in Section 2 of this document; all apply where relevant. 3.3 Supplementary Planning Documents (SPDs) will be prepared where appropriate to provide detailed guidance on particular policies and proposals. In particular, Development Briefs will be prepared to provide detailed guidance on the implementation of the main site allocations. Improving access to the Waterside 3.4 The Transport section (7.9) of the Core Strategy notes that access to Totton and the Waterside is “not so good”, particularly as the A326 is often congested. Core Strategy Policy CS23 states support for improvements that reduce congestion, improve accessibility and improve road safety. Core Strategy Policy CS23 also details some specific transport proposals in Totton and the Waterside that can help achieve this. The transport schemes detailed below are those that are not specific to a particular settlement within the Totton and Waterside area, but have wider implications for this area as a whole. -

September 2018-August 2019

Blashford Lakes Annual Report 2018-19 September 2018-August 2019 Wild Day Out – exploring the new sculpture trail © Tracy Standish Blashford Lakes Annual Report 2018-2019 Acknowledgements The Blashford Project is a partnership between Bournemouth Water, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust and Wessex Water During the period of 2018-2019 we are also very grateful to New Forest District Council for a grant towards the day to day running costs of managing the Centre and Nature Reserve, New Forest LEADER for their grant towards improving the visitor experience at Blashford Lakes (in particular the installation of wildlife camera’s for viewing by the public and the visitor improvements to the environs inside and immediately around the Centre) and to Veolia Environmental Trust, with money from the Landfill Communities Fund, for the creation of a new wildlife pond, the construction of a new hide and a volunteer manned visitor information hub and improvements to site interpretation and signage. The Trust would also like to acknowledge and thank the many members and other supporters who gave so genererously to our appeal for match funding. Thank you also to the Cameron Bespolka Trust for their generous funding and continued support of our Young Naturalist group. Publication Details How to cite report: No part of this document may be reproduced without permission. This document should be cited as: author, date, publisher etc. For information on how to obtain further copies of this document Disclaimers: and accompanying data please contact Hampshire & Isle of Wight All recommendations given by Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Wildlife Trust: [email protected] Trust (HIWWT) are done so in good faith and every effort is made to ensure that they are accurate and appropriate however it is the Front cover: sole responsibility of the landowner to ensure that any actions they Wild Day Out – exploring the new sculpture trail © Tracy Standish take are both legally and contractually compliant. -

NEW FOREST HEART Monthly Beat Report – March 2021

NEW FOREST HEART Monthly Beat Report – March 2021 Once again, at the time of writing, we are still under COVID-19 restrictions. The best way to keep up to date with all the latest news on the Government’s roadmap out of lockdown is to read the latest on their website (www.gov.uk). Thank you Several fines were issued to those breaking the COVID-19 regulations in March. They included a family of four who had driven to Boltons Bench from Dorset, a professional hairdresser who was still working from home in Woodlands, a man who had driven from Dorset to Hythe to visit his family and another two familes who had driven from Poole to go for a walk at Denny Wood and the Canadian War Memorial. Beat Surgeries We will be holding two more of our SAFE AT HOME EVENTS in April 2021. If you, or someone you know, needs our help and it is easier to visit us in person we will be outside the COMMUITY CENTRE in LYDHURST at 3pm on Tuesday 6th April 2021 and outside the CO OP in ASHURST at 10am on Wednesday 21st April 2021 Seven sheds, garages and outbuildings were broken into during March with Bramshaw, Lyndhurst, Bartley, Fletchwood Lane and Emery Down the areas targeted. A man has been arrested and charged with stealing a Quad bike from a house in Ashurst. The Quad bike has also been returned to the owner. Thirteen vehicles were broken into last month, with the two car parks targeted being Wilverly Inclosure and the one attached to the Premier Inn at Ower where three vans were attacked on the same night.