Arxiv:1602.05963V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 11 Apr 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet Nine Join the Hunt for a Possible Planet!

Planet Nine Join the Hunt for a Possible Planet! In July 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft gave us our first close look at Pluto, the most famous dwarf planet in the outskirts of our Solar System. The flyby was big news, and the data sent back to Earth revealed a world far more complex than anyone realized. Are there more worlds out there, beyond Pluto? What might such a world be like? Planet Nine tells a tale of the search for another world hidden in the darkness. Planetary scientist-explorers continually make discoveries about conditions "out there". Planet Nine follows Mike Brown and his team at CalTech as they uncover new worlds such as the remarkably bright Eris; tumbling Haumea, an Exploring Farther egg-shaped object rotating incredibly fast; and Sedna, whose High-powered telescopes peer out at the sky each night, orbit takes it deep into the far reaches of the Solar System. searching for faint light from distant worlds. Experience a night at the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, as Brown describes his Is there a new planet beyond even these distant objects? search for worlds so far away they take thousands of years to orbit the Sun. Orbits Tell The Tale Pluto's own unusual path is a clue to chaotic activities billions of years ago. Could other distant objects "out there" follow equally odd orbits? Throughout this fascinating show, Mike Brown talks about unusual orbits and describes nights of painstaking robotic searches for new planets. His is a story of modern planet- hunting techniques that have uncovered many new worlds out beyond Neptune. -

"Planet Nine": Have Astronomers Found a Huge New World Past Pluto? by Scientific American, Adapted by Newsela Staff 01.25.16

Name: ______________________________ Period: ______ Date: _____________ Article of the Week Directions: Read the following article carefully and annotate. You need to include at least 1 annotation per paragraph. Be sure to include all of the following in your total annotations. Annotation = Marking the Text + A Note of Explanation 1. Great Idea or Point – Write why you think it is a good idea or point – ! 2. Confusing Point or Idea – Write a question to ask that might help you understand – ? 3. Unknown Word or Phrase – Circle the unknown word or phrase, then write what you think it might mean based on context clues or your word knowledge – 4. A Question You Have – Write a question you have about something in the text – ?? 5. Summary – In a few sentences, write a summary of the paragraph, section, or passage – # "Planet Nine": Have astronomers found a huge new world past Pluto? By Scientific American, adapted by Newsela staff 01.25.16 Picture and Caption ___________________________ ___________________________ ___________________________ ___________________________ Paragraph #1 This picture is an artist’s depiction of what "Planet Nine" might look like. The planet is thought to be gaseous, similar to Uranus and Neptune, and in our solar system out ___________________________ beyond Pluto. Photo: Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC) ___________________________ Para #1 In the last 20 years, astronomers have identified about 2,000 new worlds using a telescope in space. These planets ___________________________ orbit stars that lie tens or even hundreds of light-years from Earth. These discoveries are important, but no single planet is likely to ___________________________ be much of a big deal. -

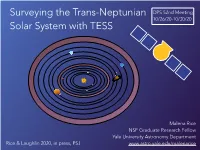

Surveying the Trans-Neptunian Solar System with TESS

Surveying the Trans-Neptunian DPS 52nd Meeting 10/26/20-10/30/20 Solar System with TESS Malena Rice NSF Graduate Research Fellow Yale University Astronomy Department Rice & Laughlin 2020, in press, PSJ www.astro.yale.edu/malenarice 30 au Adapted from Batygin & Brown 2016 Planet Nine ? Batygin, Adams, Brown, & Becker 2019 Planet Nine ? 400-800 au semimajor axis Batygin, Adams, Brown, & Becker 2019 Planet Nine ? 5-10 Earth masses 400-800 au semimajor axis Batygin, Adams, Brown, & Becker 2019 Planet Nine ? 5-10 Earth masses 400-800 au semimajor axis 15-25° inclination Batygin, Adams, Brown, & Becker 2019 0.2-0.5 eccentricity Planet Nine ? 5-10 Earth masses 400-800 au semimajor axis 15-25° inclination Batygin, Adams, Brown, & Becker 2019 Video: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center \ How do we recover signals over 300x dimmer than Pluto? Sedna’s sky motion How do we recover signals over 300x dimmer than Pluto? tinyurl.com/sednarecovery • Automated local maximum finder • Automated local maximum finder • Injection recovery tests • Automated local maximum finder • Injection recovery tests • False positive vetting with two independent baseline subtraction methods Paper I Focus: Ongoing Work and The Galactic Plane Future Directions • Motivation: Point sources can • Incorporate neural “hide” in the galactic plane networks for automated candidate vetting in a • Applied the algorithm to larger-scale, all-sky survey search TESS sectors 18 and 19 for candidate outer solar • Extend to additional system objects science cases by • Developed and applied the considering a different framework for a TESS shift- range of orbital paths stacking pipeline Image from TESS/MIT Video by Tony Dunn Thank you! Rice & Laughlin 2020, in press, PSJ (on arxiv tonight) DPS talk: 304.03 [email protected] Web summary: astro.yale.edu/malenarice/#researchhighlight4 @malena_rice. -

The Observer

The Observer The Official Publication of the Lehigh Valley Amateur Astronomical Society http://www.lvaas.org 610-797-3476 http://www.facebook.com/lvaas.astro December 2016 Volume 56 Issue 12 ad ast ra* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * One of the most intriguing mysteries in contemporary astronomy was the subject of out November meeting. Boyejian?s Star, also known as Tabby?s Star as well as the Where?s the Flux star, is flickering occasionally, like a Christmas light that is loose in its broken socket, and nobody can explain why. Dr. Joshua Pepper from Lehigh University reviewed the findings and the potential explanations that have been proposed, none of which are considered very satisfying at the moment. This was a great presentation, because mysteries like this are the kind of thing that keeps science interesting, and it will be very cool to finally figure out what it is. For now, I hope we are all looking forward to our upcoming Holiday party! This year we are going to try something new. I often join some work friends at Jack Callaghan's Ale House in Allentown for a fun night of competition, doing my best to dig the answers out of the back of my brain to questions that I previously had no reason to A portion of the mysterious light curve of Boyajian's Star care about, and often learning something in the process. LVAAS? first Trivia Contest will take place at our Holiday party on December 10. Remember to bring some eats to share with your fellow attendees. Also remember to keep an eye on http://lvaas.org in case of bad weather, and we need to reschedule to December 11. -

The Adler Planetarium Launches New Sky Show, Planet Nine, on May 28

Media Inquiries Contact: Christina O’Connell 312-542-2424 [email protected] The Search Is On! The Adler Planetarium Launches New Sky Show, Planet Nine, on May 28. CHICAGO – May 6, 2016 – The Adler Planetarium’s newest sky show, Planet Nine, opening May 28, explores the largest of Pluto’s neighbors in the Kuiper belt and invites visitors to join in the search for a new ninth planet. In July 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft gave us our first close look at Pluto, the most famous dwarf planet in the outskirts of our Solar System. The New Horizons flyby was big news, and the pictures it continues to send back to Earth reveal a world far more complex than anyone realized. Using nothing but their wits (and high-powered telescopes and a thorough understanding of orbital mechanics), these intrepid explorers are making new discoveries about how our Solar System formed—and what it may be hiding. “We are excited to be releasing our newest sky show, especially in light of news on a potential ninth planet lurking in our Solar System,” says Mark SubbaRao, Ph.D., astronomer and Director of the Space Visualization Laboratory at the Adler Planetarium. “After Mike Brown’s Kavli Prize Laureate lecture at the Adler last spring, we decided to collaborate on a sky show. Our new sky show will provide our visitors a glimpse into the very latest science, including the evidence as to why we think another large planet is out there.” Mike Brown was one of three recipients of the 2012 Kavli Prize in Astrophysics, which was awarded for discovering and characterizing the Kuiper Belt and its largest members -- work that led to a major advance in the understanding of the history of our planetary system. -

![Arxiv:1902.10103V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 26 Feb 2019](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3063/arxiv-1902-10103v1-astro-ph-ep-26-feb-2019-2923063.webp)

Arxiv:1902.10103V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 26 Feb 2019

The Planet Nine Hypothesis Konstantin Batygin,1 Fred C. Adams,2;3 Michael E. Brown,1 and Juliette C. Becker3 1Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 2Physics Department, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA 3Astronomy Department, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA Abstract Over the course of the past two decades, observational surveys have unveiled the intri- cate orbital structure of the Kuiper Belt, a field of icy bodies orbiting the Sun beyond Neptune. In addition to a host of readily-predictable orbital behavior, the emerging census of trans-Neptunian objects displays dynamical phenomena that cannot be ac- counted for by interactions with the known eight-planet solar system alone. Specifi- cally, explanations for the observed physical clustering of orbits with semi-major axes in excess of ∼ 250 AU, the detachment of perihelia of select Kuiper belt objects from Neptune, as well as the dynamical origin of highly inclined/retrograde long-period or- bits remain elusive within the context of the classical view of the solar system. This newly outlined dynamical architecture of the distant solar system points to the exis- tence of a new planet with mass of m9 ∼ 5 − 10 M⊕, residing on a moderately inclined orbit (i9 ∼ 15 − 25 deg) with semi-major axis a9 ∼ 400 − 800 AU and eccentricity between e9 ∼ 0:2 − 0:5. This paper reviews the observational motivation, dynamical constraints, and prospects for detection of this proposed object known as Planet Nine. 1. Introduction Understanding the solar system’s large-scale architecture embodies one of human- ity’s oldest pursuits and ranks among the grand challenges of natural science. -

The Search for Planet Nine Is a Neptune-Size World Hidden in Our Solar System? by Stephanie Warren Drimmer Art by Mondolithic

THE SEARCH FOR PLANET NINE IS A NEPTUNE-SIZE WORLD HIDDEN IN OUR SOLAR SYSTEM? BY STEPHANIE WARREN DRIMMER ART BY MONDOLITHIC GET MORE! SPACE natgeokids.com/space 18 MARCH 2017 PLANET NINE ay out in the farthest While observing the belt in 2014, the planet would be roughly the size of reaches of the solar system, Brown and his research partner, Neptune. Like Neptune, it would likely be a mysterious undiscovered Konstantin Batygin, saw something made of gas, and the temperature there Wplanet orbits through space. It’s strange: The orbits of many of the would be a frigid minus 374.8°F. gigantic—almost four times the size of smaller objects in the Kuiper belt were “It’s hard to believe that we could Earth. And it’s so far away that it takes aligned. Weirder still, they never came miss something as big as Neptune!” up to 20,000 years to orbit the sun. closer to the sun than Neptune. It was Brown says. But the planet is really far This planet isn’t science fiction. like something was pulling them away. away, about 56 billion miles from Earth. Astronomers think it really exists. But what? Only a little light would hit it. If it exists, They’ve dubbed it Planet Nine, and only two telescopes in the world are they’re searching the skies to find it. S TRANGE SPACE powerful enough to search vast areas of Brown and Batygin spent over a year the sky for it efficiently—and until now, FAR OUT trying to figure out the objects’ odd they haven’t been looking for the planet. -

Is There a Planet Nine in Our Solar System? There Is a Lot More to Our Solar System Than Eight Planets Going Around the Sun

Is There a Planet Nine in Our Solar System? There is a lot more to our solar system than eight planets going around the Sun. For example, between Mars and Jupiter, there is an asteroid belt filled with small rocky objects. These objects are leftover bits that didn’t get swept up when the planets were forming. Out beyond Neptune, there’s another belt of small bits of icy debris, known as the Kuiper Belt. All those icy objects in the Kuiper Belt are simply known as Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs), the most famous of which is the dwarf planet (and former planet number nine) Pluto. Although the planets orbit in near perfect circles around the Sun, not everything in our solar system is so well-behaved. Kuiper Belt Objects and comets tend to have very eccentric orbits, meaning their paths around the Sun are more like stretched out ovals, dipping close to the Sun and then traveling much further away. All small objects of the solar system—comets, KBOs, asteroids—change their orbits as they encounter each other and the larger things of the solar system, like the planets. Earth’s orbit changes a bit, too, as it is pulled on by the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn. Our solar system is always changing, even if it might not seem like it from Earth! Because KBOs are so far away and so small, not much sunlight is reflected off them and they appear quite dim from our point of view. Only recently, have we had telescopes powerful enough to let us track the KBO orbits—and it turns out they’re pretty strange. -

Hunt for Planet Nine: Atmosphere, Spectra, Evolution, and Detectability

Digital Collections @ Dordt Faculty Work Comprehensive List 6-2016 Hunt for Planet Nine: Atmosphere, Spectra, Evolution, and Detectability Jonathan J. Fortney University of California, Santa Cruz Mark S. Marley NASA Ames Research Center Gregory Laughlin University of California, Santa Cruz Nadine Nettelmann University of Rostock Caroline V. Morley University of California, Santa Cruz See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons Recommended Citation Fortney, J. J., Marley, M. S., Laughlin, G., Nettelmann, N., Morley, C. V., Lupu, R. E., Visscher, C., Jeremic, P., Khadder, W. G., & Hargrave, M. (2016). Hunt for Planet Nine: Atmosphere, Spectra, Evolution, and Detectability. Astrophysical Journal Letters, 824 (2) https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8205/824/2/L25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Work Comprehensive List by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hunt for Planet Nine: Atmosphere, Spectra, Evolution, and Detectability Abstract We investigate the physical characteristics of the solar system's proposed Planet Nine using modeling tools with a heritage of studying Uranus and Neptune. For a range of plausible masses and interior structures, we find upper limits on the intrinsic , from ~35 to 50 K for masses of 5–20 M ⊕, and we also explore lower values. Possible planetary radii could readily span from 2.7 to 6 R ⊕, depending on the mass fraction of any H/He envelope. -

Beyond Neptune, a Chunk of Ice Is Orbiting the Sun in the Wrong Direction 17 August 2016, by Matt Williams

Beyond Neptune, a chunk of ice is orbiting the sun in the wrong direction 17 August 2016, by Matt Williams the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System 1 Survey (Pan-STARRS 1). Measuring just 200 km (124 miles) in diameter, this object's orbit is tilted 110° to the plane of the solar system and orbits the sun backwards. Ordinarily, when planetary systems form, angular momentum forces everything to spin in the same direction. Hence why, when viewed from the celestial north pole, all the objects in our solar system appear to be orbiting the sun in a counter- clockwise direction. So when objects orbit the sun in the opposite direction, an outside factor must be at play. An artist’s concept of a trans-Neptunian object(TNOs). The distant sun is reduced to a bright star at a distance of over 3 billion miles. Credit: NASA Beyond the orbit of Neptune, the farthest recognized-planet from our sun, lies the mysteries population known as the Trans-Neptunian Object (TNOs). For years, astronomers have been discovering bodies and minor planets in this region which are influenced by Neptune's gravity, and orbit our sun at an average distance of 30 Astronomical Units. Artist’s impression of Planet Nine as an ice giant In recent years, several new TNOs have been eclipsing the central Milky Way, with a star-like Sun in the discovered that have caused us to rethink what distance. Neptune’s orbit is shown as a small ellipse constitutes a planet, not to mention the history of around the Sun. -

Mysterious "Planet Nine" May Be Causing Whole Solar System to Wobble

Name: _______________________________________ English IV: NTI Day 2 Assignment Mysterious "Planet Nine" may be causing whole solar system to wobble By Sarah Kaplan, Washington Post 10.27.16 This artistic rendering shows the distant view from "Planet Nine" back toward the sun. The planet is thought to be gaseous, similar to Uranus and Neptune. Photo: Handout from Caltech/R. Hurt, IPAC Astronomers can't see "Planet Nine." But it makes its presence known. The massive hypothetical object, which supposedly looms at the edge of our solar system, has been invoked to explain the strange clustering of objects in the Kuiper belt and the unusual way they orbit the sun. Now Planet Nine predictors Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown of Caltech, along with graduate student Elizabeth Bailey, offer another piece of evidence for the elusive sphere's existence: It adds "wobble" to the solar system, they say, tilting it in relation to the sun. "Because Planet Nine is so massive and has an orbit tilted compared to the other planets, the solar system has no choice but to slowly twist out of alignment," lead author Bailey said in a statement. Before we go any further, a caveat about Planet Nine: It's purely theoretical at this point. Batygin and Brown predict its existence based on unusual perturbations of the solar system that aren't otherwise easily explained. (This is the same technique scientists used to find Neptune.) But the history of astronomy is rife with speculations that never bear out: The same guy who correctly predicted the existence of Neptune also believed that a planet he called Vulcan was responsible for the wobble of Mercury. -

Présentation Powerpoint

The Solar system Kuiper belt (30-50 AU) KBO=Kuiper Belt Object • Can be roughly divided into the classical belt and the resonances. Resonances are orbits linked to that of Neptune (e.g. twice for every three Neptune orbits, or once for every two). • Makemake (45.79 AU average), although smaller than Pluto, is the largest known object in the classical Kuiper belt (KBO not in a confirmed resonance with Neptune). • The dwarf planet Pluto (39 AU average) is the largest known object in the Kuiper belt. When discovered in 1930, it was considered to be the ninth planet; this changed in 2006 with the adoption of a formal definition of planet (3/2 resonance with Neptune) Typical objects in KBO Comparison of the orbits of scattered disc objects (black), classical KBOs (blue), and 2:5 resonant objects (green). Orbits of other KBOs are gray. (Orbital axes have been aligned for comparison.) Trans-neptunian planets – Similar to Uranus or Neptune, but formed directly at 125-250 AU? – Formed closer and scattered by the giant planets ealry in SS history? – Captured from another planetary system? Discovery of Sedna-like body Trujillo & Sheppard, Nature 507, 471 (2014) Surveyed 52 deg2 of sky for new inner Oort cloud objects using the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) at CTIO 4-m telescope: each patch imaged 3 times with 1.5 h to 2 h between images to detect the motion of objects beyond 300 AU when compared to background stars + position and colour of 2012 VP 113 measured using the Magellan 6.5-m telescope ® Consistent with simulated Super Earth-mass body at 250