Interests of Amicus Curiae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue Bell Creameries, LP, Amarillo, TX, State Inspection

Texas Department of State Health Services 1100 West 49th St. Austin, Texas 78756 Inspections Unit Inspection Summary Report rev. 11-12a Firm Name: License#: Blue Bell Creameries LP Amarillo Transfer Station NoneCFN ~ Address: Scope of Inspection: 5101 South Washington FDA Contract Inspection City, State Zip: Start Date: I End Date: Amarillo, Texas 791 10 26 March 13 26 March 13 -TABLE OF CONTENTS ... INSPECTION NARRATIVE (including Table of Contents) ATIACHMENTS E-14 Detention Disposition of Detained Products Destruction Sample Receipt Chain of Custody (Copy) EXHIBITS Complaint D Substantiated 0 Not Substantiated D Closed Drop Down Menu Reason Product Labels NOT attached: Drop Down Menu Drop Down Menu Drop Down Menu No. of Photos: Photo Name: Domestic Seafood HACCP Report Form 3501 (Seafood Inspection) HACCP Plan HACCP Records Sanitation Monitoring Records Invoices/Bills of Lading OTHER 1 -INSPECTION NARRATIVE- I. FIRM DATA ntials Mr. Brad Duggan, Territory Operations Managers Manager Legal ress A LP - Partnership Other: Austin, Beumont, Brenham, Corpus, Dallas, Longview, Ft Worth, Houston, Humble, Huntsville, Katie, Lufkin, New Braunsfield, Lewisville, Mckenne, San Antonio, Lancaster, Harlengen, Waco, El Paso, Amarillo 5101 South Washington 79110, Big Spring 401 East 1-20 79270, Odessa 1515 Windcrest 79763, Abaline 525 Fudwifer Road 79603 Firm Website: N/A I Only): Corporate Officers: rm.E: NAME; rmt:: NAME: IMr. Paul Kruse Mr. Bill Rankin Management & Responsibilities: Mr. Brad Duggan Territory Operations Manager FDA Summary Information: The current routine inspection of Blue Bell Creameries was conducted by DSHS under FDA contract FY13 and in Accordance with CPGM 7303.803. The firm is a frozen food transfer station that distributes ice-cream and frozen desserts Throughout out of itsEJmsq. -

In the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware Ms

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE MS. MARY GIDDINGS WENSKE, : INDIVIDUALLY AND AS TRUSTEE OF : THE THOMAS HUNTER GIDDINGS, JR. : TRUST U/W/O THOMAS H. GIDDINGS : DATED 5/23/2000, : : Plaintiffs, : : v. : C.A. No. 2017-0699-JRS : BLUE BELL CREAMERIES, INC., BLUE : BELL CREAMERIES, U.S.A., INC., : PAUL W. KRUSE, JIM E. KRUSE, : HOWARD W. KRUSE, GREG BRIDGES, : RICHARD DICKSON, WILLIAM J. : RANKIN, DIANA MARKWARDT, : JOHN W. BARNHILL, JR., PAUL A. : EHLERT, DOROTHY MCLEOD : MACINERNEY, PATRICIA RYAN, : : Defendants. : : and : : BLUE BELL CREAMERIES, L.P., : : Nominal Defendant. : MEMORANDUM OPINION Date Submitted: April 18, 2018 Date Submitted: July 6, 2018 Jessica Zeldin, Esquire of Rosenthal, Monhait & Goddess, P.A., Wilmington, Delaware and Scott G. Burdine, Esquire and David E. Wynne, Esquire of Burdine Wynne LLP, Houston, Texas, Attorneys for Plaintiffs. Timothy R. Dudderar, Esquire and Travis R. Dunkelberger, Esquire of Potter Anderson & Corroon LLP, Wilmington, Delaware, Attorneys for Defendants Blue Bell Creameries, Inc., Blue Bell Creameries, U.S.A., Inc., Jim E. Kruse, Howard W. Kruse, Richard Dickson, William J. Rankin, Diana Markwardt, John W. Barnhill, Jr., Paul A. Ehlert, Dorothy McLeod MacInerney, Patricia Ryan, and Nominal Defendant Blue Bell Creameries, L.P. Srinivas M. Raju, Esquire and Kelly L. Freund, Esquire of Richards, Layton & Finger, P.A., Wilmington, Delaware, Attorneys for Defendants Greg Bridges and Paul W. Kruse. SLIGHTS, Vice Chancellor Whether conduct is right or wrong in the eyes of the law, actionable or not actionable, depends in large part upon the standard by which the conduct is measured. A driver operating a motor vehicle at 70 miles per hour on Route One in Dover, Delaware is driving in excess of the posted 65 miles per hour speed limit. -

Why Richmond?

Why Richmond? Richmond, Virginia, has a central place in America's history. It was here that the nation's founding fathers were inspired to set into motion the creation of our country. We’re one of America's oldest cities yet we’re tops in attracting the sought-after millennial workforce, in large part thanks to our robust higher education institutions. Companies from across the globe are attracted to the Richmond region, much like the ten Fortune 1000 companies headquartered here. And there are many others with a major presence or divisional headquarters. Over the last five years, Richmond has had the highest job growth rate in the Commonwealth with the population migration to match. Here are just a few of the reasons why companies and workforce are selecting Richmond, Va. for expansion or relocation. Strategic geography located at the mid-point of the east coast. Richmond, Va. is ideal for companies looking for strong infrastructure network of roads (I-95, I-64, I-85), ports (the Richmond Marine Terminal connects to the Port of Virginia, one of the nation’s largest seaports), air (Richmond International Airport – named one of the most efficient in North America) and rail (only place in the U.S. where three Class I railroads cross above ground at the same location). Simply put, it’s easy to move goods and people to, through and within Greater Richmond. More than 45 percent of the nation’s population can be accessed within a one-day drive. And living here, you’re less than two hours from both the beach and the mountains or our nation’s capital, providing a vast selection of day trip options. -

Securities Offerings

SECURITIES OFFERINGS STATE NOTICES Blue Bell Creameries, L.P. 1101 S. Blue Bell Rd., Brenham, TX 77833 Published pursuant to provisions of General Business Law Partnership — Blue Bell Creameries, Inc. [Art. 23-A, § 359-e(2)] Celebvidy LLC 7712 Tiny Tortoise St., Las Vegas, NV 89149 DEALERS; BROKERS State or country in which incorporated — Nevada CION Investment Corporation 13 Arch/Rebuke, LLC Three Park Ave., 36th Fl., New York, NY 10016 800 Arbor Dr. N, Louisville, KY 40223 State or country in which incorporated — Maryland 13 Colonel John/Mystery Bullet, LLC Citrine Energy Capital, L.P. 800 Arbor Dr. N, Louisville, KY 40223 2100 McKinney Ave., Suite 1625, Dallas, TX 75201 Partnership — Citrine Energy Capital GP, L.P. 13 Street Boss/Sweet Sierra, LLC 800 Arbor Dr. N, Louisville, KY 40223 Claypond Commons Investment, LLC 5619 DTC Pkwy., Suite 800, Greenwood Village, CO 80111 2467274 Ontario Inc. 40 Old Bridle Path, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4T 1A7 Compassionate Care Center of New York, LLC State or country in which incorporated — Canada One Old Country Rd., Suite 125, Carle Place, NY 11514 State or country in which incorporated — New York AEA Investors Fund VI LP 666 Fifth Ave., 36th Fl., New York, NY 10103 Corporate Property Associates 18 – Global Incorporated Partnership — AEA Investors Fund VI LP 50 Rockefeller Plaza, New York, NY 10020 State or country in which incorporated — Maryland Aggreko plc 120 Bothwell St., Glasgow, G2 7JS United Kingdom Cypress Partners L.P., The State or country in which incorporated — Scotland 865 S. Figueroa St., Suite 700, Los Angeles, CA 90017 Partnership — The Cypress Funds LLC, general partner Alexin LLC 1390 S. -

BLUE BELL CREAMERIES Leading Ice Cream Brand Hosting & Managed Services

BLUE BELL CREAMERIES Leading Ice Cream Brand Hosting & Managed Services ABOUT EMTEC ® FIRM PROFILE Emtec is the right size provider of technology-empowered Blue Bell Creameries is ranked in the top three best-selling ice cream business solutions for world class brands in the United States with the majority of sales in 22 states. organizations. Our local offices, highly-skilled associates, and Founded in 1907, Blue Bell’s Headquarters is in Brenham, Texas and global delivery capabilities ensure the accessibility and scale to align operates manufacturing facilities in Brenham, Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, technology solutions with your and Sylacauga, Alabama. business needs. Our collective focus is to continue to build clients for life: long-term enterprise relationships THE BUSINESS CHALLENGE that deliver rapid, meaningful, and lasting business value. Blue Bell has been an Oracle user since 1997. qualified, in-house resources that would drive Years ago, Blue Bell decided to outsource their the upgrade project, but needed Emtec’s Oracle DBA responsibilities and the hosting ClearCARE team to offset missing skill sets APPLICATION SERVICES of their Oracle environments to a third party and serve as an extension of their existing Emtec provides support and provider. They pursued a partner who could team. expertise throughout the entire provide comprehensive hosting, database and application lifecycle. application support services. By engaging RESULTS Oracle On-Demand, Blue Bell selected Emtec We help clients reduce costs, Blue Bell has utilized Emtec’s hosting and to provide hosting and DBA managed services. streamline processes and gain database administration services for over six efficiencies through better utilization THE SOLUTION years. -

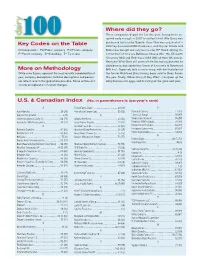

Key Codes on the Table More on Methodology Where Did They

Where did they go? Three companies depart the list this year, having been ac- quired early enough in 2007 to not be listed. Alto Dairy was Key Codes on the Table purchased last year by Saputo, Cass Clay was acquired at in 2007 by Associated Milk Producers, and Crystal Cream and C=Cooperative Pu=Public company Pr=Private company Butter was bought out early last year by HP Hood. Joining the P=Parent company S=Subsidiary T= Tie in rank list for the first time are BelGioso Cheese (No. 75), Ellsworth Creamery (84) and Roth Kase USA (96) all from Wisconsin. Next year Winn-Dixie will come off the list, having divested its dairy processing capabilities (some of it recently to Southeast More on Methodology Milk Inc.). Supervalu tells a similar story, with the final plant of While sales figures represent the most recently completed fiscal the former Richfood Dairy having been sold to Dean Foods year, company descriptions, facilities descriptions and person- this year. Finally, Wilcox Dairy of Roy, Wash., has given up the nel reflect recent changed where possible. Some entries will dairy business for eggs, and its listing will be gone next year. include an explanation of recent changes. U.S. & Canadian Index (No. in parentheses is last year’s rank) A Foster Farms Dairy ....................................... 50 (48) P Agri-Mark Inc. .............................................. 29 (29) Friendly Ice Cream Corp. ...............................55 (56) Parmalat Canada .........................................12 (13) Agropur Cooperative .........................................6 (9) G Perry’s Ice Cream ........................................ 97 (97) Anderson Erickson Dairy Co. ......................... 66 (71) Glanbia Foods Inc. ........................................ 23 (32) Plains Dairy Products ....................................95 (99) Associated Milk Producers Inc. -

Former Blue Bell Creameries President Charged in Connection with 2015 Ice Cream Listeria Contamination IOPA I Department of Just

10/22/2020 Former Blue Bell Creameries President Charged In Connection With 2015 Ice Cream Listeria Contamination IOPA I Department of Just. .. II§ An official website of the United States government Here's how you know Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, October 21 , 2020 Former Blue Bell Creameries President Charged In Connection With 2015 Ice Cream Listeria Contamination A Texas grand jury charged the former president of ice cream manufacturer Blue Bell Creameries L.P. with wire fraud and conspiracy in connection with an alleged scheme to cover up the company's sales of Listeria-tainted ice cream in 2015, the Justice Department announced today. In an indictment filed in federal court in Austin, Texas, former Blue Bell president Paul Kruse was charged with seven counts of wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud related to his alleged efforts to conceal from customers what the company knew about Listeria contamination in certain Blue Bell products. According to the indictment, Texas state officials notified Blue Bell in February 2015 that two ice cream products from the company's Brenham, Texas, factory tested positive for Listeria monocytogenes, a dangerous pathogen that can lead to serious illness or death in vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, newborns, the elderly, and those with compromised immune systems. Kruse allegedly orchestrated a scheme to deceive certain Blue Bell customers, including by directing employees to remove potentially contaminated products from store freezers without notifying retailers or consumers about the real reason for the withdrawal. The indictment alleges that Kruse directed employees to tell customers who asked about the removal that there was an unspecified issue with a manufacturing machine. -

Eleventh Circuit Holds That New Value Need Not Remain Unpaid for Section 547(C)(4) Defense to Apply in Preference Actions by David Wender and Tom Clinkscales

WWW.ALSTON.COM Bankruptcy & Financial Restructuring ADVISORY n AUGUST 28, 2018 Eleventh Circuit Holds That New Value Need Not Remain Unpaid for Section 547(c)(4) Defense to Apply in Preference Actions by David Wender and Tom Clinkscales On August 14, 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit held that a preference defendant may reduce its preference exposure to a debtor or trustee in bankruptcy by the value of the goods or services supplied to the debtor by that supplier after the transfers in question occurred, regardless of whether the “new value” remains unpaid. Under Section 547 of the Bankruptcy Code, a debtor in bankruptcy can avoid a transfer of an interest of the debtor in property made to a creditor within the 90 days before the filing of the debtor’s bankruptcy petition (the “preference period”) if the transfer was (1) made while the debtor was insolvent; (2) made on account of an antecedent debt owed by the debtor to the creditor; which (3) allowed the creditor to receive more than it would have received in a Chapter 7 case had the transfer not been made; unless (4) the defendant can show the existence of one of the defenses set out in Section 547(c). One of the Section 547(c) defenses is the “new value” defense, which holds that a transfer is not avoidable under Section 547 if the creditor provided valuable goods or services to the debtor after the otherwise- avoidable transfer occurred (and before the debtor’s bankruptcy petition was filed) that was “(A) not secured by an otherwise unavoidable security interest; and (B) on account of which new value the debtor did not make an otherwise unavoidable transfer to or for the benefit of such creditor” up to the amount of the new value delivered. -

For Immediate Release Consumer Contact:979-836-7977 For

For Immediate Release Consumer Contact: 979-836-7977 For Frequently Asked Questions click here. BLUE BELL CREAMERIES VOLUNTARILY EXPANDS RECALL TO INCLUDE ALL OF ITS PRODUCTS DUE TO POSSIBLE HEALTH RISK BRENHAM, Texas, April 20, 2015 –Blue Bell Ice Cream of Brenham, Texas, is v oluntarily recalling all of its products currently on the market made at all of its facilities including ice cream, frozen yogurt, sherbet and frozen snacks because they have the potential to be contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes, an organism which can cause serious and sometimes fatal infections in young children, frail or elderly people, and others with weakened immune systems. Although healthy individuals may suffer only short-term symptoms such as high fever, severe headaches, stiffness, nausea, abdominal pain and diarrhea, Listeria infection can cause miscarriages and stillbirths among pregnant women. “We’re committed to doing the 100 percent right thing, and the best way to do that is to take all of our products off the market until we can be confident that they are all safe,” said Paul Kruse, Blue Bell CEO and president. “We are heartbroken about this situation and apologize to all of our loy al Blue Bell fans and customers. Our entire history has been about making the very best and highest quality ice cream and we intend to fix this problem. We want enjoying our ice cream to be a source of joy and pleasure, never a cause for concern, so we are committed to getting this right.” The products being recalled are distributed to retail outlets, including food serv ice accounts, convenience stores and supermarkets in Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Wyoming and international locations*. -

Former Blue Bell Creameries President Charged in Connection with 2015 Ice Cream Listeria Contamination

Case 1:20-cr-00249-RP Document 1 Filed 10/20/20 Page 1 of 18 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS 2121 OCT 20 PM 3: 47 AUSTIN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, } CRIMINAL NO. } Plaintiff. } A20 CR RP } VIOLATIONS: 249 v. } 18 u.s.c. §1343 } 18 u.s.c. §1349 PAUL KRUSE, } 18 u.s.c. §2 } Defendant. } INDICTMENT The United States Charges: INTRODUCTION 1. Blue Bell Creameries, L.P. ("Blue Bell"), was a Delaware limited partnership that manufactured and sold various ice cream products. The company was headquartered in Brenham, Texas, and manufactured ice cream at plants in Brenham, Texas ("Brenham Facility"), Broken Arrow, Oklahoma ("Broken Arrow Facility"), and Sylacagua, Alabama. Blue Bell engaged in and affected interstate commerce. Between 2011 and 2015, Blue Bell had more than $2.5 billion in total gross sales. 2. Blue Bell operated as a direct store delivery company. This meant Blue Bell controlled the distribution of products from its manufacturing plants to approximately 62 regional distribution centers and then directly to the freezers of its customers. 3. Blue Bell's customers included schools, hospitals, United States military bases, grocery stores, and convenience stores. 1 Case 1:20-cr-00249-RP Document 1 Filed 10/20/20 Page 2 of 18 4. At times relevant to this Indictment, Blue Bell delivered its products to customers in 23 states. 5. Blue Bell employed several levels of sales employees, including driver salesmen who placed the products directly in customers' freezers, territory managers who oversaw routes, branch managers who oversaw territories, and regional managers who oversaw branches. -

Blue Bell Creameries, Inc., Brenham, TX 483 Response Dated 5/22/15

= Blue Bell Creameries, Inc. Loop577, P.O. Box 1807 Brenham, Texas 77834-1807 ( 409) 836-7977 May22, 2015 Mr. Reynaldo Rod riguez District Director Dallas District Office U.S. Food and Drug Administration 4040 North Central Expressway Dallas, Texas 75204-3128 Re : Responses of Blue Bell Creameries, Inc., to FDA Form 483s Dear Mr. Rodriguez, Blue Bell Creameries, Inc., (Blue Bell or the Company) appreciates the opportunity to respond to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Form 483 lnspectional Observations (the 483s) issued to our ice cream processing facilities in Brenham, Texas, and Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. We are responding separately to the New Orleans District regarding the FDA Form 483 issued to our facility in Sylacauga, Alabama. Producing safe, wholesome products for our consumers to enjoy is Blue Bell's highest priority, and we are taking this situation very, very seriously. Since the initial recall, we have consistently sought to make the right decisions based on the best available evidence and in full cooperation with FDA and our state regulators. We conducted multiple recalls based on the most recently available test results, culminating in a recall of all of our products so we can be certain consumers are ·safe. Our sole mission is to ensure all aspects of our facilities and production lines are clean and sanitary and will result in safe product for our consumers. We have assembled a team with deep expertise in food safety to help us address these issues. 114 6 {4 and a team of expert scientific consultants are working with the Company in thoroughly analyzing all aspects of our facilities and our operations. -

Bankruptcy Forms

B7 (Official Form 7) (12/07) United States Bankruptcy Court Western District of Louisiana In re Legends Gaming, LLC Case No. 12-12017 Debtor(s) Chapter 11 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL AFFAIRS This statement is to be completed by every debtor. Spouses filing a joint petition may file a single statement on which the information for both spouses is combined. If the case is filed under chapter 12 or chapter 13, a married debtor must furnish information for both spouses whether or not a joint petition is filed, unless the spouses are separated and a joint petition is not filed. An individual debtor engaged in business as a sole proprietor, partner, family farmer, or self-employed professional, should provide the information requested on this statement concerning all such activities as well as the individual's personal affairs. To indicate payments, transfers and the like to minor children, state the child's initials and the name and address of the child's parent or guardian, such as "A.B., a minor child, by John Doe, guardian." Do not disclose the child's name. See, 11 U.S.C. § 112; Fed. R. Bankr. P. 1007(m). Questions 1 - 18 are to be completed by all debtors. Debtors that are or have been in business, as defined below, also must complete Questions 19 - 25. If the answer to an applicable question is "None," mark the box labeled "None." If additional space is needed for the answer to any question, use and attach a separate sheet properly identified with the case name, case number (if known), and the number of the question.