Stephen Long and Scientific Exploration on the Plains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Navigation on the Yellowstone River

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1950 History of navigation on the Yellowstone River John Gordon MacDonald The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation MacDonald, John Gordon, "History of navigation on the Yellowstone River" (1950). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2565. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2565 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY of NAVIGATION ON THE YELLOWoTGriE RIVER by John G, ^acUonald______ Ë.À., Jamestown College, 1937 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Mas ter of Arts. Montana State University 1950 Approved: Q cxajJL 0. Chaiinmaban of Board of Examiners auaue ocnool UMI Number: EP36086 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Ois8<irtatk>n PuUishing UMI EP36086 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Edwin James's Nineteenth-Century Cross-Cultural Collaborations Kyhl Lyndgaard University of Nevada, Reno

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Winter 2010 Landscapes of Removal and Resistance: Edwin James's Nineteenth-Century Cross-Cultural Collaborations Kyhl Lyndgaard University of Nevada, Reno Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Lyndgaard, Kyhl, "Landscapes of Removal and Resistance: Edwin James's Nineteenth-Century Cross-Cultural Collaborations" (2010). Great Plains Quarterly. 2519. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2519 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. LANDSCAPES OF REMOVAL AND RESISTANCE EDWIN JAMES'S NINETEENTH,CENTURY CROSS,CULTURAL COLLABORATIONS KYHL LYNDGAARD The life of Edwin James (1797-1861) is book One reason for James's obscurity is the willing ended by the Lewis and Clark expedition ness he had to collaborate with others. Both (1803-6) and the Civil War (1861-65) (Fig. 1). of his major works, Account of an Expedition James's work engaged key national concerns of from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains (1823) western exploration, natural history, Native and A Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures American relocation, and slavery. His prin of John Tanner (1830), as well as many of his cipled stands for preservation of lands and articles, were published with his name listed animals in the Trans-Mississippi West and his as editor or compiler rather than as author. -

Eldean Bridge NHL Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ELDEAN BRIDGE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Eldean Bridge (preferred historic common name) Other Name/Site Number: Allen’s Mill Bridge (original historic name); Marshall Bridge; World Guide #35-55-01; Farver Road Bridge 0.15 2. LOCATION Street Address: Spanning Great Miami River at bypassed section of Eldean Road/CR33 (bypassed section of Eldean Road is now the west part of Farver Road) Not for Publication: City/Town: Troy vicinity, Concord Township-Staunton Township Vicinity: X State: Ohio County: Miami Code: 055 Zip Code: 45373 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: ___ Building(s): ___ Public-Local: X District: ___ Public-State: ___ Site: ___ Public-Federal: ___ Structure: X Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing buildings buildings sites sites 1 structures structures objects objects 1 Total 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related MultipleDRAFT Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ELDEAN BRIDGE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The Work of General Henry Atkinson, 1819-1842

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1937 In Defense of the Frontier: The Work of General Henry Atkinson, 1819-1842 Alice Elizbeth Barron Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Barron, Alice Elizbeth, "In Defense of the Frontier: The Work of General Henry Atkinson, 1819-1842" (1937). Master's Theses. 42. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/42 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1937 Alice Elizbeth Barron IN DErINSE or THE FRONTIER THE WORK OF GENERAL HDRl' ATKINSON, 1819-1842 by ALICE ELIZABETH BARROI( A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE or MASTER or ARTS 1n LOYOLA UNIVERSITY 1937 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. A HISTORICAL SKETCH ............•..•.•.•• 1 First Indian Troubles Henry Atkinson's Preparation for the Frontier CHAPTER II. THE YELLOWSTONE EXPEDITION OF 1819 .••••.• 16 Conditions in the Upper Missouri Valley Calhoun's Plans The Expedition Building of Camp Missouri CHAPTER III. THE FIGHT FOR THE YELLOWSTONE EXPEDITION •• 57 Report on the Indian Trade The Fight for the Yellowstone Expedition Calhoun's Report - The Johnson Claims Events at Camp Missouri - Building ot Fort Atkinson The Attack on the War Department CHAPTER IV. -

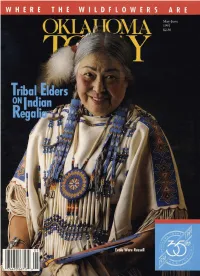

Oklahoma Today May-June 1991 Volume 41 No. 3

WHERE THE WILQFlQWFRc ARL OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA OKLAHOMA rnDN May-June 1991 Vnl dl, Nn -4 I FEATURES I WILDFLOWER REDUX 8 After decades as targets of sprayers, mowers, and bad-mouthers, Oklahoma's native plants are the new stars of garden and roadside. A look at a wildflower renaissance in full bloom. By BurkhardBilger HAVE PICNIC BASKET, WILL TRAVEL 19 Swing by for lunch on your way somewhere else or spend the afternoon under a shade tree. These four city parks are top picks for picnics. By Susan Wittand Barbara Palmer, photographs by Fred W.Marvel PORTFOLIO: OKLAHOMA TRIBESMEN 22 The regalia worn by Oklahoma tribes links the past and the present and is a source of identity for both young and old. Photographs by David Fitzgerald ZEN AND THE ART OF BICYCLE TOURING 28 Toiling up a brutal hill and sailing down the ocher side. Broiling at high noon and floating on an evening breeze. All are part of the cycle of life, one learns along the course of the Freewheel bike tour. By Joel Everett, photographs by Scott Andenen RIDING WITH RED 36 There are plenty of laurels for Red is still up at dawn, out training for yet another bicycle endurance tour. By Teq Phe/ps, photographs by Scott Andem TODAY IN OKLAHOMA 4 IN SHORT 5 LETTERS 6 OMNIBUS Chautauqua 'Til You Drop, by Douz Bentin 7 FOOD TheOnion-Fried Burger, by Bar(iara Palmer 39 WEEKENDER Red Earth, by Jeanne M. Dtwlin 41 ARTS Best of the West, by Marcia Preston 44 ENTERTAINMENT CALENDAR A guide to what's happening 49 COVER: Kiowa storyteller Evalu Ware Russell of Anadarko at Red Earth. -

(1822) and London (1823) Editions of Edwin James's

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey 2010 History and dating of the publication of the Philadelphia (1822) and London (1823) editions of Edwin James’s Account of an expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains Neal Woodman USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Woodman, Neal, "History and dating of the publication of the Philadelphia (1822) and London (1823) editions of Edwin James’s Account of an expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains" (2010). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 582. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/582 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archives of natural history 37 (1): 28–38. 2010 # The Society for the History of Natural History DOI: 10.3366/E0260954109001636 History and dating of the publication of the Philadelphia (1822) and London (1823) editions of Edwin James’s Account of an expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains NEAL WOODMAN USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, MRC-111, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA (e-mail: [email protected]). ABSTRACT: The public record of Major Stephen H. Long’s 1819–1820 exploration of the American north-west, Account of an expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains, compiled by Edwin James, contains valuable contributions regarding the natural landscapes, native peoples and wildlife of a mostly unexplored region of the American west compiled from the notes of some of America’s foremost naturalists, and it includes the first descriptions of 67 new species. -

Vol. 40/ 6 (1967)

Newspapers on the Minnesota Frontier, 1849— to persuade prospective settlers and townsmen 1860. By GEORGE S. HAGE. (St. Paul, Min to migrate to Minnesota. Characteristic of these nesota Historical Society, 1967. ix, 176 p. are editor James M. Goodhue's florid enthusi Illustrations. $4.50.) asms in the columns of the Minnesota Pioneer. Even on the brink of the 1857 depression in Reviewed by Ralph D. Casey the Northwest, the Minnesotian's spokesman re jected pessimism and cited "happy examples of MR. HACK'S scholarly account of the frontier Western speculation and Minnesota's full har newspapers of Minnesota is a model of press vest." history. It neither places undue stress on the Intent on impressing officialdom in the na editorial thunderers of the pioneer society, nor tion's capital, and impelled to sing the praises does it become a sociological treatise ignoring of the Minnesota area, the editors always wrote the significant role played by the irrepressible with one eye on the eastern papers, with which crew of journalists who helped to make Minne they exchanged their own. Meantime, they neg sota articulate. The author has recognized that lected the news at their own doorsteps. If the press was not an independent agency. His they thought seriously about local reporting, history is a balanced account of the reciprocal the Minnesota writers no doubt rationalized relationship between jom"nals and journalists that the average pioneer would not miss the and the setting of which they were a part. account of local events, as he would quickly The task of extracting historical nuggets from learn of them without the help of a paper. -

Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819-1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences Great Plains Studies, Center for 2008 Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819-1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory Hugh H. Genoways University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Brett C. Ratcliffe University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons, Plant Sciences Commons, and the Zoology Commons Genoways, Hugh H. and Ratcliffe, Brett C., "Engineer Cantonment, Missouri Territory, 1819-1820: America's First Biodiversity Ineventory" (2008). Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences. 927. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsresearch/927 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Research: A Journal of Natural and Social Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Great Plains Research 18 (Spring 2008):3-31 © 2008 Copyright by the Center for Great Plains Studies, University of Nebraska-Lincoln ENGINEER CANTONMENT, MISSOURI TERRITORY, 1819-1820: AMERICA'S FIRST BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY Hugh H. Genoways and Brett C. Ratcliffe Systematic Research Collections University o/Nebraska State Museum Lincoln, NE 68588-0514 [email protected] and [email protected] ABSTRACT-It is our thesis that members of the Stephen Long Expedition of 1819-20 completed the first biodiversity inventory undertaken in the United States at their winter quarters, Engineer Cantonment, Mis souri Territory, in the modern state of Nebraska. -

Fort Atkinson at Council Bluffs

Fort Atkinson at Council Bluffs (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Sally A Johnson, “Fort Atkinson at Council Bluffs,” Nebraska History 38 (1957): 229-236 Article Summary: The author presents the history of Fort Atkinson and questions still surrounding its origins. New interest in the site of the post arose during the summer of 1956 when a Nebraska State Historical Society field party, under the direction of Marvin F Kivett, did some archeological work there. There was a bill before Congress to make the site a national monument at that time. Cataloging Information: Names: Marvin F Kivett, Lewis and Clark, John Ordway, John Colter, George Drouillard, John Potts, Peter Wiser, Manuel Lisa, Patrick Gass, S H Long, J R Bell, Henry Atkinson, John C Calhoun, T S Jessup Keywords: Missouri Trading Company, St Louis; Engineer Cantonment; Fort Lisa; Cantonment Council Bluffs; Omaha Indians; Ninth Military Department; Water Witch (lead boat in the move to Jefferson Barracks); Yellowstone Expedition Photographs / Images: Meeting of Lewis and Clark with Oto and Missouri Indians at Council Bluffs, 1804 (painting reconstructed by Herbert Thomas, staff artist, Nebraska State Historical Society) FORT ATKINSON AT COUNCIL BLUFFS BY SALLY A. -

The Military Frontier on the Upper Missouri

The Military Frontier on the Upper Missouri (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Ray H Mattison, “The Military Frontier on the Upper Missouri,” Nebraska History 37 (1956): 159- 182 Article Summary: Many military posts were built on the Upper Missouri at the beginning of the nineteenth century as the United States struggled to keep its frontier secure against various Indian tribes. The Army gradually abandoned the posts as the Indian frontier disappeared. Cataloging Information: Names: Manuel Lisa, Henry Atkinson, J L Grattan, William S Harney, G K Warren, John Pope, Henry H Sibley, Alfred H Sully, P H Sheridan, Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull Trading Companies: Missouri Fur Company, Rocky Mountain Fur Company, American Fur Company Army Posts: Camp Missouri (later Cantonment Missouri), Fort Atkinson, Fort Yates, Fort Rice, Fort Benton, Fort Stevenson, Fort Hale, Fort Bennett, Fort Shaw, Fort Lookout, Fort Randall, Fort Sully, Fort Buford, Camp Poplar, Fort Omaha Keywords: Arikara, Sioux, Cheyenne, Treaty of 1868, “Custer Massacre,” Bighorn, Ghost Dance Rebellion Photographs / Images: interior of Fort Rice, Dakota Territory; Fort Abraham Lincoln, near Bismarck, North Dakota; Fort Hale, near Chamberlain, South Dakota; Battalion, Twenty-Fifth US Infantry, Fort Randall THE MILITARY FRONTIER ON THE UPPER MISSOURI BY RAY H. -

Alcohol Bottles at Fort Snelling: a Study of American Military Culture in the 19Th Century

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in Cultural Resource Management Department of Anthropology 12-2020 Alcohol Bottles at Fort Snelling: A Study of American Military Culture in the 19th Century Katherine Gaubatz Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/crm_etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Gaubatz, Katherine, "Alcohol Bottles at Fort Snelling: A Study of American Military Culture in the 19th Century" (2020). Culminating Projects in Cultural Resource Management. 39. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/crm_etds/39 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in Cultural Resource Management by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alcohol Bottles at Fort Snelling: A Study of American Military Culture in the 19th Century by Katherine “Rin” Gaubatz A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Cultural Resources Management Archaeology December 2020 Thesis Committee: Rob Mann, Chairperson Debra Gold Emily Schultz 2 Abstract The goal of this research was to explore the theme of alcohol as a social status marker within the realm of the American military frontier in the early to mid-1800s. The study was done as a comparison between the drinking habits of the officers and the enlisted men throughout the occupancy of the selected fort during the 1800s. -

Indian Wars.8-98.P65

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Research Collections in Native American Studies The Indian Wars of the West and Frontier Army Life, 18621898 Official Histories and Personal Narratives UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of THE INDIAN WARS OF THE WEST AND FRONTIER ARMY LIFE, 1862–1898 Official Histories and Personal Narratives Project Editor and Guide Compiled by: Robert E. Lester A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Indian wars of the West and frontier army life, 1862–1898 [microform] : official histories and personal narratives / project editor, Robert E. Lester microfiche. Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Robert E. Lester, entitled: A guide to the microfiche edition of The Indian wars of the West and frontier army life, 1862–1898. ISBN 1-55655-598-9 (alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America--Wars--1862–1865--Sources. 2. Indians of North America--Wars--1866–1895--Sources. 3. United States. Army--Military life--History--19th century--Sources. 4. West (U.S.)--History--19th century--Sources. I. Lester, Robert. II. University Publications of America (Firm) III. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of The Indian wars of the West and frontier army life, 1862–1898. [E81] 978'.02—dc21 98-12605 CIP Copyright © 1998 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-598-9. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Scope and Content Note ................................................................................................. v Arrangement of Material .................................................................................................. ix List of Contributing Institutions ..................................................................................... xi Source Note .....................................................................................................................