Police Power in the Italian Communes, 1228–1326

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

It 2.007 Vc Italian Films On

1 UW-Madison Learning Support Services Van Hise Hall - Room 274 rev. May 3, 2019 SET CALL NUMBER: IT 2.007 VC ITALIAN FILMS ON VIDEO, (Various distributors, 1986-1989) TYPE OF PROGRAM: Italian culture and civilization; Films DESCRIPTION: A series of classic Italian films either produced in Italy, directed by Italian directors, or on Italian subjects. Most are subtitled in English. Individual times are given for each videocassette. VIDEOTAPES ARE FOR RESERVE USE IN THE MEDIA LIBRARY ONLY -- Instructors may check them out for up to 24 hours for previewing purposes or to show them in class. See the Media Catalog for film series in other languages. AUDIENCE: Students of Italian, Italian literature, Italian film FORMAT: VHS; NTSC; DVD CONTENTS CALL NUMBER Il 7 e l’8 IT2.007.151 Italy. 90 min. DVD, requires region free player. In Italian. Ficarra & Picone. 8 1/2 IT2.007.013 1963. Italian with English subtitles. 138 min. B/W. VHS or DVD.Directed by Frederico Fellini, with Marcello Mastroianni. Fellini's semi- autobiographical masterpiece. Portrayal of a film director during the course of making a film and finding himself trapped by his fears and insecurities. 1900 (Novocento) IT2.007.131 1977. Italy. DVD. In Italian w/English subtitles. 315 min. Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. With Robert De niro, Gerard Depardieu, Burt Lancaster and Donald Sutherland. Epic about friendship and war in Italy. Accattone IT2.007.053 Italy. 1961. Italian with English subtitles. 100 min. B/W. VHS or DVD. Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini's first feature film. In the slums of Rome, Accattone "The Sponger" lives off the earnings of a prostitute. -

Coins and Identity: from Mint to Paradise

Chapter 13 Coins and Identity: From Mint to Paradise Lucia Travaini Identity of the State: Words and Images on Coins The images and text imprinted with dies transformed disks of metal into coins and guaranteed them. The study of iconography on coins is therefore no less important than that of its other aspects, although each coinage should be studied together with the entire corpus of data and especially with reference where possible to its circulation.1 It may be difficult sometimes to ascertain how coin iconography was originally understood and received, but in most cases it is at least possible to know the idea behind the creation of different types, the choice of a model or of a language, as part of a crucial interaction of identity between the State and its coinage. We shall examine first some ex- amples of the creative phase, before minting took place, and then examples of how a sense of identity between the coins and the people who used them can be documented, concluding with a very peculiar use of coins as proof of identity for security at the entrance of gates of fortresses at Parma and Reggio Emilia in 1409.2 1 St Isidore of Seville stated in his Etymologiae that “in coins three things are necessary: metal, images and weight; if any of these is lacking it is not a coin” (in numismate tria quaeren- tur: metallum, figura et pondus. Si ex his aliquid defuerit nomisma non eriit) (Isidore of Seville, Origenes, Vol. 16, 18.12). For discussion of method, see Elkins and Krmnicek, Art in the Round, and Kemmers and Myrberg, “Rethinking numismatics”. -

Middle Ages of the City

Chapter 5 Merchants and Bowmen: Middle Ages of the City Once past, dreams and memories are the same thing. U. piersanti, L’uomo delle Cesane (1994) It’s a beautiful day in May. We find ourselves in Assisi, the city of saints Francis and Clare. The “Nobilissima parte de sopra” and the “Magnifica parte de sotto” (the Most Noble Upper Part and the Magnificent Lower Part), which represent the districts of the city’s theoretical medieval subdivision, challenge each oth- er to a series of competitions: solemn processions, feats of dexterity, songs, challenges launched in rhyme, stage shows. In this way, it renews the medieval tradition of canti del maggio (May songs), performed in the piazzas and under girls’ balconies by bands of youths wandering the city. A young woman is elect- ed Madonna Primavera (Lady Spring). We celebrate the end of winter, the return of the sun, flowers, and love. This medieval festival, resplendent with parades, flag bearers, ladies, knights, bowmen, and citizen magistrates, re- sounding with songs, tambourines, and trumpets, lasts three days and involves the entire population of Assisi, which finds itself, together with tourists and visitors, immersed in the atmosphere of a time that was. At night, when the fires and darkness move the shadows and the natural odors are strongest, the magic of the illusion of the past reaches its highest pitch: Three nights of May leave their mark on our hearts Fantasy blends with truth among sweet songs And ancient history returns to life once again The mad, ecstatic magic of our feast.1 Attested in the Middle Ages, the Assisan Calendimaggio (First of May) reap- peared in 1927 and was interrupted by the Second World War, only to resume in 1947. -

J Ewish Community and Civic Commune In

Jewish community and civic commune in the high Middle Ages'' CHRISTOPH CLUSE 1. The following observations do not aim to provide a comprehensive phe nomenology of the J ewish community during the high and late medieval periods. Rather 1 wish to present the outlines of a model which describes the status of the Jewish community within the medieval town or city, and to ask how the concepts of >inclusion< and >exclusion< can serve to de scribe that status. Using a number of selected examples, almost exclusively drawn from the western regions of the medieval German empire, 1 will concentrate, first, on a comparison betweenJewish communities and other corporate bodies (>universitates<) during the high medieval period, and, secondly, on the means by which Jews and Jewish communities were included in the urban civic corporations of the later Middle Ages. To begin with, 1 should point out that the study of the medieval Jewish community and its various historical settings cannot draw on an overly rich tradition in German historical research. 1 The >general <historiography of towns and cities that originated in the nineteenth century accorded only sporadic attention to the J ews. Still, as early as 1866 the legal historian Otto Stobbe had paid attention to the relationship between the Jewish ::- The present article first appeared in a slightly longer German version entitled Die mittelalterliche jüdische Gemeinde als »Sondergemeinde« - eine Skizze. In: J OHANEK, Peter (ed. ): Sondergemeinden und Sonderbezirke in der Stadt der Vormoderne (Städteforschung, ser. A, vol. 52). Köln [et al.] 2005, pp. 29-51. Translations from the German research literature cited are my own. -

A Century of Turmoil

356-361-0314s4 10/11/02 4:01 PM Page 356 TERMS & NAMES 4 •Avignon A Century • Great Schism • John Wycliffe • Jan Hus • bubonic plague of Turmoil • Hundred Years’ War MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW • Joan of Arc During the 1300s, Europe was torn apart Events of the 1300s led to a change in by religious strife, the bubonic plague, attitudes toward religion and the state, and the Hundred Years’ War. a change reflected in modern attitudes. SETTING THE STAGE At the turn of the century between the 1200s and 1300s, church and state seemed in good shape, but trouble was brewing. The Church seemed to be thriving. Ideals of fuller political representation seemed to be developing in France and England. However, the 1300s were filled with disasters, both natural and manmade. By the end of the century, the medieval way of life was beginning to disappear. A Church Divided At the beginning of the 1300s, the papacy seemed in some ways still strong. Soon, however, both pope and Church were in desperate trouble. Pope and King Collide The pope in 1300 was an able but stubborn Italian. Pope Boniface VIII attempted to enforce papal authority on kings as previous popes had. When King Philip IV of France asserted his authority over French bishops, Boniface responded with a papal bull (an official document issued by the pope). It stated, “We declare, state, and define that subjection to the Roman Vocabulary Pontiff is absolutely necessary for the salvation of every Pontiff: the pope. human creature.” In short, kings must always obey popes. -

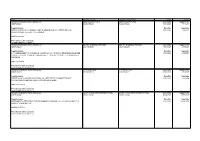

Lotto Operatori Invitati Operatori Aggiudicatari Tempi Importo Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse BISSON AUTO S.P.A

Lotto Operatori invitati Operatori aggiudicatari Tempi Importo Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse BISSON AUTO S.P.A. BISSON AUTO S.P.A. Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 02202650244 02202650244 16/06/2021 1.518,27€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato BISSON AUTO S.P.A., GRUMOLO DELLE ABBADESSE (VI) - INTERVENTO DI 31/12/2021 1.246,32€ MANUTENZIONE AUTOMEZZO COMUNALE CIGZ283208993 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse BETTIO GABRIELE PER.IND BETTIO GABRIELE PER.IND Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 02483070245 02483070245 17/06/2021 2.550,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato P.I. GABRIELE BETTIO, CAMISANO VICENTINO (VI) - INCARICO PROFESSIONALE PER 31/12/2021 2.550,00€ PROGETTO DI ADEGUAMENTO IMPIANTO ELETTRICO EX SCUOLE ELEMENTARI DI SARMEGO CIGZF53223D40 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse FORTE NICOLA FORTE NICOLA Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 03160660241 03160660241 04/06/2021 2.529,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato FORTE NICOLA, QUINTO VICENTINO (VI) - INTERVENTI DI MANUTENZIONE 31/12/2021 2.529,00€ STRAORDINARIA IMPIANTO ELETTRICO SCUOLE MEDIE CIGZBA31F4EFA Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse LA GOCCIA SCARL SERVIZI SOCIALI LA GOCCIA SCARL SERVIZI SOCIALI Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 00882110240 00882110240 30/04/2020 19.734,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato AFFIDAMENTO SERVIZIO DI PULIZIA IMMOBILI COMUNALI ALLA COOP.SOCIALE "LA 31/12/2021 20.894,87€ GOCCIA" DI MAROSTICA. CIGZAD2CBFE47 Procedura scelta contraente 23-AFFIDAMENTO DIRETTO Lotto Operatori invitati Operatori aggiudicatari Tempi Importo Comune Di Grumolo Delle Abbadesse PMP SRL PMP SRL Data inizio Aggiudicato 80007250246 02580430029 02580430029 29/01/2021 525,00€ Oggetto bando Data fine Liquidato PMP S.R.L., 360169 THIENE (VI). -

Minutes of a Meeting of the Industrial Commission of North Dakota Held on October 22, 2019 Beginning at 12:30 P.M

Minutes of a Meeting of the Industrial Commission of North Dakota Held on October 22, 2019 beginning at 12:30 p.m. Governor’s Conference Room - State Capitol Present: Governor Doug Burgum, Chairman Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem Agriculture Commissioner Doug Goehring Also Present: Other attendees are listed on the attendance sheet available in the Commission files Members of the Press Governor Burgum called the Industrial Commission meeting to order at approximately 12:30 p.m. and the Commission took up Oil & Gas Research Program (OGRP) business. OIL & GAS RESEARCH PROGRAM Ms. Karlene Fine, Industrial Commission Executive Director, provided the Oil and Gas Research Fund financial report for the period ending August 31, 2019. She stated that there is $8.8 million of uncommitted funding available for project awards during the 2019-2021 biennium. Ms. Fine presented the Oil and Gas Research Council 2019-2021 budget recommendation and stated the budget includes the uncommitted dollars and the payments scheduled for projects previously approved by the Commission. It was moved by Commissioner Goehring and seconded by Attorney General Stenehjem that the Industrial Commission accepts the Oil and Gas Research Council’s recommendation and approves the following 2019-2021 biennium allocation for Oil and Gas Research Program funding: Research 46.70% $ 7,770,415 Education 8.42% $ 1,350,000 Pipeline Authority 4.37% $ 700,000 Administration 1.20% $ 300,000 Legislative Directive 39.31% $ 6,300,000 $16,420,415 and further authorizes the Industrial Commission Executive Director/Secretary to transfer $700,000 from the Oil and Gas Research Fund to the Pipeline Authority Fund during the 2019-2021 biennium. -

Br 1100S, Br 1300S

BR 1100S, BR 1300S PARTS LIST Standard Models After SN1000038925: 56413006(BR 1100S), 56413007(BR 1100S C / w/sweep system), 56413889(OBS / BR 1100S C / w/o sweep system) 56413010(BR 1300S), 56413011(BR 1300S C / w/sweep system), 56413890(OBS / BR 1300S C / w/o sweep system) Obsolete EDS Models: 56413785(BR 1100S EDS), 56413781(BR 1100S C EDS / w/sweep system), 56413782(BR 1300S EDS), 56413783(BR 1300S C EDS / w/sweep system), 56413897(BR 1100S C EDS / w/o sweep system) 56413898(BR 1300S C EDS / w/o sweep system) 5/08 revised 2/11 FORM NO. 56042498 08-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS 10-7 BR 1100S / BR 1300S 1 DESCRIPTION PAGE Chassis System ................................................................................................................................................. 2-3 Decal System ..................................................................................................................................................... 4-5 Drive Wheel System........................................................................................................................................... 6-7 Drive Wheel System (steering assembly) .......................................................................................................... 8-9 Electrical System.............................................................................................................................................10-11 Rear Wheel System ...................................................................................................................................... -

Farm Laborers' Wages in England 1208-1850

THE LONG MARCH OF HISTORY: FARM LABORERS’ WAGES IN ENGLAND 1208-1850 Gregory Clark Department of Economics UC-Davis, Davis CA 95616 [email protected] Using manuscript and secondary sources, the paper calculates real day wages for male agricultural laborers in England from 1208 to 1850. Both nominal wages and the cost of living move differently than is suggested by the famous Phelps-Brown and Hopkins series on building craftsmen. In particular farm laborers real wages were only half as much in the pre-plague years as would be implied by the PBH index. The PBH series implied that the English economy broke from the stasis of the medieval period only in the late eighteenth century. The real wage calculated here suggest that the productivity of the economy began growing from the medieval level at least a century earlier in the mid seventeenth century. INTRODUCTION The wage history of pre-industrial England is unusually well documented for a pre- industrial economy. The relative stability of English institutions after 1066, and the early development of markets, allowed a large number of documents with wages and prices to survive in the records of churches, monasteries, colleges, charities, and government. These documents have been the basis of many studies of pre-industrial wages and prices: most notably those of James E. Thorold Rogers, William Beveridge, Elizabeth Gilboy, Henry Phelps-Brown and Sheila Hopkins, Peter Bowden, and David Farmer.1 But only one of these studies, that of Phelps- Brown and Hopkins, attempted to measure real wages over the whole period. Using the wages of building craftsmen Phelps-Brown and Hopkins constructed a real wage series from 1264 to 1954 which is still widely quoted.2 This series famously established two things. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

Nailor Life Safety and Air Control Products

IINSTALLATION, OOPERATION & MMAINTENANCE MM Fire, Smoke, Ceiling AA and Control Dampers An Installation, Operation and NN Maintenance Manual for Nailor Life Safety and Air Control Products. • Curtain Type Fire Dampers UU • Multi-Blade & True Round Fire Dampers • Smoke Dampers • Combination Fire/Smoke Dampers AA • Ceiling Dampers/Fire Rated Diffusers • Accessories • Control and LL Backdraft Dampers IOM Manual Fire, Smoke, Ceiling and Control Dampers Contents Doc. Issue Date Page No. Curtain Type Fire Dampers Model Series: (D)0100, 0200, 0300, (D)0500 Factory Furnished Sleeve Details (Non-Integral Sleeve) FDSTDSL 5/02 1.010-1.011 Integral Sleeve Fire Dampers Details Model Series 01X4-XX Static FDINTSL 2/05 1.020-1.021 Model Series D01X4-XX Dynamic FDINTSLD 1/14 1.022-1.023 Fire Damper Sizing Charts: Model Series (D)0100 & (D)0500 Standard 4 1/4" Frame FDSC 5/02 1.030-1.031 Model Series 0200 & 0500 Thinline 2" Frame FDTSC 5/02 1.040-1.041 Standard Installation Instructions: Standard & Wide Frame, Series (D)0100, 0300, (D)0510-0530 FDINST 1/14 1.050-1.053 Thinline Frame, Models 0210-0240, 0570-0590 FDTINST 8/07 1.060-1.061 Hybrid Type D0100HY Series FDHYINST 9/07 1.062-1.063 Fire Damper Installation Instructions: Model Series (D)0100G, 0200G FDGINST 1/08 1.070-1.071 Out Of Wall Fire Damper Installation Instructions: Model Series (D)0110GOW FDGOWINST 5/15 1.072-1.073 Model Series (D)0110DOW FDDOWINST 6/21 1.074-1.075 Inspection & Maintenance Procedures FDIMP 3/16 1.080-1.081 Accessories: Electro-Thermal Link (ETL) FDETL 5/02 1.090-1.091 Pull-Tab Release For Spring Loaded Dampers (PT) FDPTR 5/02 1.100-1.101 6/19 Contents Page 1 of 4 Nailor Industries Inc.