Root. If You Root’S Shell, in This Example, Bash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RACF Tips Volume 3, Issue 1, January 2009

Volume 3 Issue 1 IPS RSH RACF T January For Administrators, Auditors, and Analysts 2009 Specifying a Replacement ID used to change a file's attributes for Program Control, APF Authorized, and Shared Library. with IRRRID00 . To generate commands to delete an ID and all references to it, use RACF's IRRRID00 utility. You simply enter the ID in the SYSIN DD Temporary Access with statement of the IRRRID00 job like so: CONNECT REVOKE(date) //SYSIN DD * USERX You may occasionally need to permit a user temporary access to a resource. One way to do If USERX is the owner of a profile or connect, so is to grant a group access to the resource IRRRID00 generates commands like: and connect the user to that group with a revoke date. The command to set the connect revoke CONNECT RDSADM GROUP(RACFSTC) OWNER(?USERX) date would look something like this: In these cases, you need to change ?USERX to CONNECT USERA GROUP(TEMPACC) REVOKE(1/20/09) a valid replacement ID. This can be done manually or with ISPF EDIT CHANGE. On the date specified with the revoke, RACF will no longer allow the user to have the access Alternatively, you can tell IRRRID00 which permitted to the group. If you want to remove the replacement ID to use when it builds the revoke date but leave the connect intact, enter: commands. If, for instance, you want to replace every occurrence of USERX with USERJ, enter CONNECT USERA GROUP(TEMPACC) NOREVOKE the following in the SYSIN DD: A banking client of ours used this capability to //SYSIN DD * govern access to APF-authorized libraries. -

LS-09EN. OS Permissions. SUID/SGID/Sticky. Extended Attributes

Operating Systems LS-09. OS Permissions. SUID/SGID/Sticky. Extended Attributes. Operating System Concepts 1.1 ys©2019 Linux/UNIX Security Basics Agenda ! UID ! GID ! Superuser ! File Permissions ! Umask ! RUID/EUID, RGID/EGID ! SUID, SGID, Sticky bits ! File Extended Attributes ! Mount/umount ! Windows Permissions ! File Systems Restriction Operating System Concepts 1.2 ys©2019 Domain Implementation in Linux/UNIX ! Two types domain (subjects) groups ! User Domains = User ID (UID>0) or User Group ID (GID>0) ! Superuser Domains = Root ID (UID=0) or Root Group ID (root can do everything, GID=0) ! Domain switch accomplished via file system. ! Each file has associated with it a domain bit (SetUID bit = SUID bit). ! When file is executed and SUID=on, then Effective UID is set to Owner of the file being executed. When execution completes Efective UID is reset to Real UID. ! Each subject (process) and object (file, socket,etc) has a 16-bit UID. ! Each object also has a 16-bit GID and each subject has one or more GIDs. ! Objects have access control lists that specify read, write, and execute permissions for user, group, and world. Operating System Concepts 1.3 ys©2019 Subjects and Objects Subjects = processes Objects = files (regular, directory, (Effective UID, EGID) devices /dev, ram /proc) RUID (EUID) Owner permissions (UID) RGID-main (EGID) Group Owner permissions (GID) +RGID-list Others RUID, RGID Others ID permissions Operating System Concepts 1.4 ys©2019 The Superuser (root) • Almost every Unix system comes with a special user in the /etc/passwd file with a UID=0. This user is known as the superuser and is normally given the username root. -

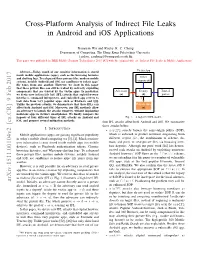

Cross-Platform Analysis of Indirect File Leaks in Android and Ios Applications

Cross-Platform Analysis of Indirect File Leaks in Android and iOS Applications Daoyuan Wu and Rocky K. C. Chang Department of Computing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University fcsdwu, [email protected] This paper was published in IEEE Mobile Security Technologies 2015 [47] with the original title of “Indirect File Leaks in Mobile Applications”. Victim App Abstract—Today, much of our sensitive information is stored inside mobile applications (apps), such as the browsing histories and chatting logs. To safeguard these privacy files, modern mobile Other systems, notably Android and iOS, use sandboxes to isolate apps’ components file zones from one another. However, we show in this paper that these private files can still be leaked by indirectly exploiting components that are trusted by the victim apps. In particular, Adversary Deputy Trusted we devise new indirect file leak (IFL) attacks that exploit browser (a) (d) parties interfaces, command interpreters, and embedded app servers to leak data from very popular apps, such as Evernote and QQ. Unlike the previous attacks, we demonstrate that these IFLs can Private files affect both Android and iOS. Moreover, our IFL methods allow (s) an adversary to launch the attacks remotely, without implanting malicious apps in victim’s smartphones. We finally compare the impacts of four different types of IFL attacks on Android and Fig. 1. A high-level IFL model. iOS, and propose several mitigation methods. four IFL attacks affect both Android and iOS. We summarize these attacks below. I. INTRODUCTION • sopIFL attacks bypass the same-origin policy (SOP), Mobile applications (apps) are gaining significant popularity which is enforced to protect resources originating from in today’s mobile cloud computing era [3], [4]. -

UPLC™ Universal Power-Line Carrier

UPLC™ Universal Power-Line Carrier CU4I-VER02 Installation Guide AMETEK Power Instruments 4050 N.W. 121st Avenue Coral Springs, FL 33065 1–800–785–7274 www.pulsartech.com THE BRIGHT STAR IN UTILITY COMMUNICATIONS March 2006 Trademarks All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or service marks are listed below. In addition, terms suspected of being trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capital- ized. Ametek cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. This publication includes fonts and/or images from CorelDRAW which are protected by the copyright laws of the U.S., Canada and elsewhere. Used under license. IBM and PC are registered trademarks of the International Business Machines Corporation. ST is a registered trademark of AT&T Windows is a registered trademark of Microsoft Corp. Universal Power-Line Carrier Installation Guide ESD WARNING! YOU MUST BE PROPERLY GROUNDED, TO PREVENT DAMAGE FROM STATIC ELECTRICITY, BEFORE HANDLING ANY AND ALL MODULES OR EQUIPMENT FROM AMETEK. All semiconductor components used, are sensitive to and can be damaged by the discharge of static electricity. Be sure to observe all Electrostatic Discharge (ESD) precautions when handling modules or individual components. March 2006 Page i Important Change Notification This document supercedes the preliminary version of the UPLC Installation Guide. The following list shows the most recent publication date for the new information. A publication date in bold type indicates changes to that information since the previous publication. -

Version 7.8-Systemd

Linux From Scratch Version 7.8-systemd Created by Gerard Beekmans Edited by Douglas R. Reno Linux From Scratch: Version 7.8-systemd by Created by Gerard Beekmans and Edited by Douglas R. Reno Copyright © 1999-2015 Gerard Beekmans Copyright © 1999-2015, Gerard Beekmans All rights reserved. This book is licensed under a Creative Commons License. Computer instructions may be extracted from the book under the MIT License. Linux® is a registered trademark of Linus Torvalds. Linux From Scratch - Version 7.8-systemd Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................................... vii i. Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................. vii ii. Audience ............................................................................................................................................................ vii iii. LFS Target Architectures ................................................................................................................................ viii iv. LFS and Standards ............................................................................................................................................ ix v. Rationale for Packages in the Book .................................................................................................................... x vi. Prerequisites -

Cygwin User's Guide

Cygwin User’s Guide Cygwin User’s Guide ii Copyright © Cygwin authors Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this documentation provided the copyright notice and this per- mission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modified versions of this documentation under the conditions for verbatim copying, provided that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this documentation into another language, under the above conditions for modified versions, except that this permission notice may be stated in a translation approved by the Free Software Foundation. Cygwin User’s Guide iii Contents 1 Cygwin Overview 1 1.1 What is it? . .1 1.2 Quick Start Guide for those more experienced with Windows . .1 1.3 Quick Start Guide for those more experienced with UNIX . .1 1.4 Are the Cygwin tools free software? . .2 1.5 A brief history of the Cygwin project . .2 1.6 Highlights of Cygwin Functionality . .3 1.6.1 Introduction . .3 1.6.2 Permissions and Security . .3 1.6.3 File Access . .3 1.6.4 Text Mode vs. Binary Mode . .4 1.6.5 ANSI C Library . .4 1.6.6 Process Creation . .5 1.6.6.1 Problems with process creation . .5 1.6.7 Signals . .6 1.6.8 Sockets . .6 1.6.9 Select . .7 1.7 What’s new and what changed in Cygwin . .7 1.7.1 What’s new and what changed in 3.2 . -

Chattr Linux Command

Linux Commands PDF – https://arkit.co.in Chattr - Linux command Change file attributes on a Linux file system using, chattr command to protect files and directories. This is an amazing option to protect your files and directories. Chattr attribute is used to stop accidentally delete of files and folder. You cannot delete the files secured via chattr attribute even though you have full permission over files. This is very use full in system files like shadow and passwd files, which contains all user information and passwords. Chattr command syntax # chattr [operator] [switch] [file name] Protect file using chattr command apply attribute ‘+i’ In this practical example, we are going to create a file and directory and provide full permission to created file and directory and apply attributes using chattr command try to delete. # touch file1 # chmod 777 file1 # ls -l total 0 -rwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 0 Jan 17 17:11 file1 # chattr +i file1 # rm -rf file1 rm: cannot remove ‘file1’: Operation not permitted # cat >> file1 -bash: file1: Permission denied List applied attributes In order to list the applied attributes, we have to use ‘lsattr’ command # lsattr file1 ----i----------- file1 Follow Us on social media: Facebook | Twitter | Reddit | LinkedIn | Website | Blog | YouTube Linux Commands PDF – https://arkit.co.in Apply attributes and append the file As we see above example when we apply an attribute ‘+i’ we cannot append, modify and delete file. Apply attribute ‘+a’ then we can append the file but we cannot delete the file. Let us see the example -

Basic Linux Security

Basic Linux Security Roman Bohuk University of Virginia What is Linux? • An open source operating system • Project started by Linus Torvalds kernel • Kernel: core program that controls everything else (controls processes, i/o between applications) • Not to be confused with Unix – commercial OS • Unix-like / *nix – broad term encompassing both Unix and Linux “Flavors” • Timeline: https://tinyurl.com/LinuxDT VM Setup • Get the VM from a flashdrive or install your own version • Login with user:UV@cnsR0cks! • 2 ways to connect it to the internet and give SSH access. In the VM network settings, select • NAT • The machine “proxies” the traffic through your NIC • Add port 22 in the port forwarding settings, and SSH to localhost • Bridged Connection • The machine has its own IP on the LAN, and you can connect to it remotely • If you want to set up a bridged connection, type ifconfig to find the MAC address, and add it at https://netreg.itc.virginia.edu/ (Register a device for network access)i VM Setup What happens when Linux boots? • BIOS looks for and executes a Master Boot Record (MBR) • MBR loads GRUB, the Linux bootloader which loads and runs the kernel • Kernel mounts the filesystem, executes the programs in /sbin/init • The init file runs the Linux at a specific “runlevel” • The runlevel-specific programs are executed from /etc/rc.d/rc*.d/ • 0 – halt • 1 – single-user mode • 2 – multiuser mode (no networking) • 3 – full multiuser mode • 5 – GUI • 6 – reboot Runlevels • Practice: who -r # prints out the current runlevel init * # changes the runlevel to * who -Ha # lists the users who are logged in Breaking Into Things Why? So you can defend it. -

Linux Pocket Guide.Pdf

3rd Edition Linux Pocket Guide ESSENTIAL COMMANDS Daniel J. Barrett 3RD EDITION Linux Pocket Guide Daniel J. Barrett Linux Pocket Guide by Daniel J. Barrett Copyright © 2016 Daniel Barrett. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebasto‐ pol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promo‐ tional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://safaribook‐ sonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or [email protected]. Editor: Nan Barber Production Editor: Nicholas Adams Copyeditor: Jasmine Kwityn Proofreader: Susan Moritz Indexer: Daniel Barrett Interior Designer: David Futato Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest June 2016: Third Edition Revision History for the Third Edition 2016-05-27: First Release See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781491927571 for release details. The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Linux Pocket Guide, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellec‐ tual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights. -

SMM Rootkits

SMM Rootkits: A New Breed of OS Independent Malware Shawn Embleton Sherri Sparks Cliff Zou University of Central Florida University of Central Florida University of Central Florida [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION The emergence of hardware virtualization technology has led to A rootkit consists of a set of programs that work to subvert the development of OS independent malware such as the Virtual control of an Operating System from its legitimate users [16]. If Machine based rootkits (VMBRs). In this paper, we draw one were asked to classify viruses and worms by a single defining attention to a different but related threat that exists on many characteristic, the first word to come to mind would probably be commodity systems in operation today: The System Management replication. In contrast, the single defining characteristic of a Mode based rootkit (SMBR). System Management Mode (SMM) rootkit is stealth. Viruses reproduce, but rootkits hide. They hide is a relatively obscure mode on Intel processors used for low-level by compromising the communication conduit between an hardware control. It has its own private memory space and Operating System and its users. Secondary to hiding themselves, execution environment which is generally invisible to code rootkits are generally capable of gathering and manipulating running outside (e.g., the Operating System). Furthermore, SMM information on the target machine. They may, for example, log a code is completely non-preemptible, lacks any concept of victim user’s keystrokes to obtain passwords or manipulate the privilege level, and is immune to memory protection mechanisms. -

Common Administrative Commands in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5, 6, 7, and 8

Common administrative commands in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5, 6, 7, and 8 System basics Kernel, boot, and hardware Basic configuration File systems, volumes, and disks TASK RHEL TASK RHEL TASK RHEL TASK RHEL /etc/sysconfig/rhn/systemid 5 6 append 1 or s or init=/bin/bash Graphical system-config-* 5 6 ext3 5 View 5 6 subscription to kernel cmdline configuration Default file information subscription-manager identity 6 7 8 Single user/ tools gnome-control-center 7 8 ext4 6 system rescue mode append 1 or s or rd.break or rhnreg_ks 6 init=/bin/bash to kernel 7 8 Text-based xfs 7 8 cmdline configuration system-config-*-tui 5 6 Configure 1, 3 tools rhn_register 5 6 7 8 ssm create 7 subscription Shut down shutdown 5 6 7 8 2 system system-config-printer 5 6 7 subscription-manager 6 7 8 Configure gdisk 7 8 printer Create/modify systemctl poweroff 7 8 gnome-control-center 8 hwbrowser 5 Power off disk partitions ssm_create 8 system system-config-date 5 6 sosreport poweroff 5 6 7 8 fdisk 5 6 7 8 5 6 7 8 dmidecode parted timedatectl 7 8 View system systemctl halt 7 8 Configure time Halt system profile lstopo and date ssm create 7 8 6 7 8 date 5 6 7 8 lscpu halt 5 6 7 8 Format disk partition mkfs.filesystem_type (ext4, xfs) gnome-control-center 8 5 6 7 8 cat/proc/cpuinfo systemctl reboot 7 8 8 mkswap lshw Reboot system /etc/ntp.conf 5 6 reboot 5 6 7 8 xfs_fsr 6 7 8 View RHEL ntpdate 5 6 7 Defragment version /etc/redhat-release 5 6 7 8 Configure /etc/inittab 5 6 disk space copy data to new file system information default run Synchronize timedatectl fsck (look for ‘non-contiguous 5 6 7 8 level/target time and date 7 8 systemctl set-default 7 8 /etc/chrony.conf inodes’) 1 Be aware of potential issues when using subscription-manager on Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5: https://access.redhat.com/solutions/129003. -

Nujj University of California, Berkeley School of Information Karen Hsu

Nujj University of California, Berkeley School of Information Karen Hsu Kesava Mallela Alana Pechon Nujj • Table of Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Problem Statement 2 Objective 2 Literature Review 3 Competitive Analysis 4 Comparison matrix 4 Competition 5 Hypothesis 6 Use Case Scenarios 7 Overall System Design 10 Server-side 12 Design 12 Implementation 12 Twitter and Nujj 14 Client-side 15 Design 17 Implementation 17 Future Work 18 Extended Functionality in Future Implementations 18 Acknowledgements 19 Abstract Nujj is a location based service for mobile device users that enables users to tie electronic notes to physical locations. It is intended as an initial exploration into some of the many scenarios made possible by the rapidly increasing ubiquity of location-aware mobile devices. It should be noted that this does not limit the user to a device with a GPS embedded; location data can now also be gleaned through methods such as cell tower triangulation and WiFi IP address lookup. Within this report, both social and technical considerations associated with exposing a user’s location are discussed. The system envisioned addresses privacy concerns, as well as attempts to overcome the poor rate of adoption of current location based services already competing in the marketplace. Although several possible use cases are offered, it is the authors’ firm belief that a well-designed location- based service should not attempt to anticipate all, or even most, of the potential ways that users will find to take advantage of it. Rather, the service should be focused on building a system that is sufficiently robust yet flexible to allow users to pursue their own ideas.