Color: a Photographer's Guide to Directing the Eye, Creating Visual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Session Outline: History of the Daguerreotype

Fundamentals of the Conservation of Photographs SESSION: History of the Daguerreotype INSTRUCTOR: Grant B. Romer SESSION OUTLINE ABSTRACT The daguerreotype process evolved out of the collaboration of Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre (1787- 1851) and Nicephore Niepce, which began in 1827. During their experiments to invent a commercially viable system of photography a number of photographic processes were evolved which contributed elements that led to the daguerreotype. Following Niepce’s death in 1833, Daguerre continued experimentation and discovered in 1835 the basic principle of the process. Later, investigation of the process by prominent scientists led to important understandings and improvements. By 1843 the process had reached technical perfection and remained the commercially dominant system of photography in the world until the mid-1850’s. The image quality of the fine daguerreotype set the photographic standard and the photographic industry was established around it. The standardized daguerreotype process after 1843 entailed seven essential steps: plate polishing, sensitization, camera exposure, development, fixation, gilding, and drying. The daguerreotype process is explored more fully in the Technical Note: Daguerreotype. The daguerreotype image is seen as a positive to full effect through a combination of the reflection the plate surface and the scattering of light by the imaging particles. Housings exist in great variety of style, usually following the fashion of miniature portrait presentation. The daguerreotype plate is extremely vulnerable to mechanical damage and the deteriorating influences of atmospheric pollutants. Hence, highly colored and obscuring corrosion films are commonly found on daguerreotypes. Many daguerreotypes have been damaged or destroyed by uninformed attempts to wipe these films away. -

Digital Camera Functions All Photography Is Based on the Same

Digital Camera Functions All photography is based on the same optical principle of viewing objects with our eyes. In both cases, light is reflected off of an object and passes through a lens, which focuses the light rays, onto the light sensitive retina, in the case of eyesight, or onto film or an image sensor the case of traditional or digital photography. The shutter is a curtain that is placed between the lens and the camera that briefly opens to let light hit the film in conventional photography or the image sensor in digital photography. The shutter speed refers to how long the curtain stays open to let light in. The higher the number, the shorter the time, and consequently, the less light gets in. So, a shutter speed of 1/60th of a second lets in half the amount of light than a speed of 1/30th of a second. For most normal pictures, shutter speeds range from 1/30th of a second to 1/100th of a second. A faster shutter speed, such as 1/500th of a second or 1/1000th of a second, would be used to take a picture of a fast moving object such as a race car; while a slow shutter speed would be used to take pictures in low-light situations, such as when taking pictures of the moon at night. Remember that the longer the shutter stays open, the more chance the image will be blurred because a person cannot usually hold a camera still for very long. A tripod or other support mechanism should almost always be used to stabilize the camera when slow shutter speeds are used. -

Paint • Digital • Production

Color paint • digital • production Color: paint, digital, production •Sarah Haig • Fall 2013 To start....a few vocabulary items: Hues – the names of the colors (red, blue, green, yellow) Value – the degree of lightness or darkness each hue has it’s own value scale ex. Yellow appears lighter than purple Intensity or Saturation – the measure of purity or brightness a color’s intensity can be lowered or decreased by mixing it with gray OR it’s compliment All color is affected by the surrounding colors and lighting. Color: paint, digital, production •Sarah Haig • Fall 2013 The color wheel that you grew up with Consists of the three primary colors: • red, yellow and blue which mix to create the secondary colors: • orange, green and purple which, in turn, mix to create the tertiary colors, that can be further mixed to create any number of colors (A LOT of them) Color: paint, digital, production •Sarah Haig • Fall 2013 These colors can be mixed to create color schemes: Monochromatic – using differing values of one hue Analogous – colors next to each other on the color wheel Complimentary – colors that are directly across from each other on the color wheel Split complimentary – any color plus the two colors adjacent to its compliment Color: paint, digital, production •Sarah Haig • Fall 2013 To start....a few vocabulary items: Hues – the names of the colors (red, blue, green, yellow) Value – the degree of lightness or darkness each hue has it’s own value scale ex. Yellow appears lighter than purple Intensity or Saturation – the measure of purity or brightness a color’s intensity can be lowered or decreased by mixing it with gray OR it’s compliment Color: paint, digital, production •Sarah Haig • Fall 2013 So....what about digital? Color: paint, digital, production •Sarah Haig • Fall 2013 Well...on screen we use RGB or red, green and blue which ADD to make white...or ADDITIVE This is the color that works most like our eyes when it comes to percieving color. -

Read Book Flower Color Theory

FLOWER COLOR THEORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK DARROCH PUTNAM | 484 pages | 03 Feb 2021 | Phaidon Press Ltd | 9781838661571 | English | London, United Kingdom Flower Color Theory PDF Book Using the color wheel is the easiest way to illustrate these concepts. Submit Information. Ask a question. While I love the color, we used a paint color match system to duplicate the color of my winter coat. It's the perfect source for planning next year's garden revamp. The color yellow is primarily associated with spreading happiness and joy, however, it is also the ideal color for symbolizing friendship. Fall color can also be assisted by late planting of some species. Any number of complementary pairs can be determined simply by shifting positions on the color wheel, but for the purposes of planning flower-color combinations, designers usually confine their discussions to the primary and secondary colors. Sign in Register Wishlist 0. In the photos above, the analogous color scheme was inspired by a dress that shifted from red to violet. Browsing through it feels joyful and clean, like walking into a well-appointed house If you have to leave these color principles behind to create your dream garden, do it. However, understanding the basic principles of using color in design can help make that picture in your head a reality. This article covers the basics on using color in your garden bed. The book features arrangements that show myriad ways to combine flowers of different hues, all built around color schemes including analogous, complementary, monochromatic, triadic, transitional, and accent colors. Customer Reviews are disabled for pre-order items. -

OSHER Color 2021

OSHER Color 2021 Presentation 1 Mysteries of Color Color Foundation Q: Why is color? A: Color is a perception that arises from the responses of our visual systems to light in the environment. We probably have evolved with color vision to help us in finding good food and healthy mates. One of the fundamental truths about color that's important to understand is that color is something we humans impose on the world. The world isn't colored; we just see it that way. A reasonable working definition of color is that it's our human response to different wavelengths of light. The color isn't really in the light: We create the color as a response to that light Remember: The different wavelengths of light aren't really colored; they're simply waves of electromagnetic energy with a known length and a known amount of energy. OSHER Color 2021 It's our perceptual system that gives them the attribute of color. Our eyes contain two types of sensors -- rods and cones -- that are sensitive to light. The rods are essentially monochromatic, they contribute to peripheral vision and allow us to see in relatively dark conditions, but they don't contribute to color vision. (You've probably noticed that on a dark night, even though you can see shapes and movement, you see very little color.) The sensation of color comes from the second set of photoreceptors in our eyes -- the cones. We have 3 different types of cones cones are sensitive to light of long wavelength, medium wavelength, and short wavelength. -

Guided Tour of Color Space

A Guided Tour of Color Space Charles Poynton This article describes the theory of color repro- dent radiation with different spectral response duction in video, and some of the engineering curves. Because there are exactly three types of compromises necessary to make practical color photoreceptors, three components are cameras and practical coding systems. necessary and sufficient to describe a color, providing that appropriate spectral weighting Video processing is generally concerned with functions are used: Color vision is inherently color represented in three components derived trichromatic. from the scene, usually red, green, and blue or components computed from these. Once red, A fourth type of photoreceptor cell, the rod, is green, and blue components of a scene are also present in the retina. Rods are effective only obtained, color coding systems transform these at extremely low light intensities. Because there components into other forms suitable for is only one type of rod cell, “night vision” cannot processing, recording, and transmission. Accu- perceive color. Image reproduction takes place at rate color reproduction depends on knowledge light levels sufficiently high that the rod recep- of exactly how the physical spectra of the orig- tors play no role. inal scene are transformed into these compo- nents and exactly how the color components are Isaac Newton said, “Indeed rays, properly transformed to physical spectra at the display. expressed, are not colored.” Spectral power distributions (SPDs) exist in the physical world, I use the term luminance and the symbol Y to but color exists only in the eye and the brain. refer to true, CIE luminance, a linear-light quan- tity proportional to physical intensity. -

ARTS 2356 Photography I ASSIGNMENT: PHOTOGRAMS DUE

ARTS 2356 Photography I ASSIGNMENT: PHOTOGRAMS DUE: Assignment: Photograms Photography is often associated with “reality” or the capturing of “reality”. For a beginning photographer, the significance of this assignment is to experience the photographic medium without the distraction of this familiar association between photography and “reality.” A photogram consists of a photographic print or image being made without the traditional use of a negative. A photogram is made by placing any two or three dimensional object or objects between a light source and light-sensitive photographic paper. A wide range of values and details may be achieved with this process depending on the nature (shape, opacity, reflective quality texture, etc.) of the objects used. While making photograms all elements of design (composition, form, line, value, etc.) should be considered. For this assignment you will make several photograms on 8x10 paper. Use the images of landscapes/environments/place and still-lifes that you have collected in your journal as a guide for your photograms. You may choose to emulate an individual image directly or use combinations of the images to build a new composition. You may find it helpful to make simplified sketches of the original images. Study the images and sketches in your journal, giving consideration to the following: value (lights/darks), line, shape, pattern, texture, and composition. Collect objects considering their physicals properties such as shape, contour, reflective quality, texture, and opacity and how you think light will react... reflect and/or pass-through these objects. Please do not bring liquids or fine powdery/grainy/gritty substances to use for your photogram assignment.. -

Evolution of Photography: Film to Digital

University of North Georgia Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository Honors Theses Honors Program Fall 10-2-2018 Evolution of Photography: Film to Digital Charlotte McDonnold University of North Georgia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation McDonnold, Charlotte, "Evolution of Photography: Film to Digital" (2018). Honors Theses. 63. https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/honors_theses/63 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository. Evolution of Photography: Film to Digital A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of North Georgia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Art in Studio Art, Photography and Graphic Design With Honors Charlotte McDonnold Fall 2018 EVOLUTION OF PHOTOGRAPHY 2 Acknowledgements I would like thank my thesis panel, Dr. Stephen Smith, Paul Dunlap, Christopher Dant, and Dr. Nancy Dalman. Without their support and guidance, this project would not have been possible. I would also like to thank my Honors Research Class from spring 2017. They provided great advice and were willing to listen to me talk about photography for an entire semester. A special thanks to my family and friends for reading over drafts, offering support, and advice throughout this project. EVOLUTION OF PHOTOGRAPHY 3 Abstract Due to the ever changing advancements in technology, photography is a constantly growing field. What was once an art form solely used by professionals is now accessible to every consumer in the world. -

Intro to Digital Photography.Pdf

ABSTRACT Learn and master the basic features of your camera to gain better control of your photos. Individualized chapters on each of the cameras basic functions as well as cheat sheets you can download and print for use while shooting. Neuberger, Lawrence INTRO TO DGMA 3303 Digital Photography DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY Mastering the Basics Table of Contents Camera Controls ............................................................................................................................. 7 Camera Controls ......................................................................................................................... 7 Image Sensor .............................................................................................................................. 8 Camera Lens .............................................................................................................................. 8 Camera Modes ............................................................................................................................ 9 Built-in Flash ............................................................................................................................. 11 Viewing System ........................................................................................................................ 11 Image File Formats ....................................................................................................................... 13 File Compression ...................................................................................................................... -

REDISCOVER the WORLD of ANALOG PHOTOGRAPHY Rollei Cinestill Revolog Cinestill Rollei

CHOICES We carry the world’S LARGEST SELECTION of black & white and color film in almost every format that you can imagine! Take a sneak peek at some cool choices inside or check out our huge selection online. Check it out! www.FreestylePhoto.Biz Rollei CineStill Revolog PRSRT STD U.S. POSTAGE PAID PHOTO & IMAGING SUPPLIES FREESTYLE 5124 Sunset Boulevard Hollywood, CA 90027 800.292.6137 FreestylePhoto.Biz REDISCOVER THE WORLD OF WORLD THE REDISCOVER ANALOG PHOTOGRAPHY ANALOG NEW AGAIN! NEW 800.292.6137 PHOTO & IMAGING & PHOTO | FreestylePhoto.Biz SUPPLIES © Trevor Masid Trevor © What a unique time period to be a photographer ! Everyone is taking pictures. We document every event, and even non-events, T? in an instant. Our cell phones have more photographs taken with them than WHA calls made. The amount of photography produced is the greatest it has ever … From a Paintcan been in any time period. Social media has opened up an entire new world with LegacyPro Paintcan and a whole new generation of photographers. Pinhole Camera (page 7) THE JOURNEY IS ANALOG! So, what are we doing producing an Analog Catalog? … With a box with Ars Imago Lab Box (page 22) Thanks to all of the above, the interest in photography has increased as a whole. So why not go back to our roots! Living in this online world has not only created a new generation interested in experimentation, but also a renewed passion for the arts in its many facets…old and new! This has led to a boom in new and one-of-a-kind film stocks, a resurgence in all formats, and a desire for alternative processes and hand-made images. -

Color Schemes Are Combinations of Colors

Color is the reflection of light off of an object into our eyes. Our eyes then read the speed of the light and tell us which color that object is. There are two major categories under the heading of color, they are: 1. Neutrals 2. Colors Neutrals are (combinations of) black and white and all grays Colors consist of: Primary colors Secondary colors Intermediate colors also known as Tertiary colors Primary Colors: are the basic colors that you cannot make by mixing. They are natural colors found in nature. They are red, yellow, and blue. Secondary Colors: are made by mixing any two secondary colors. The secondary colors are orange, violet and green. Intermediate Colors: are made by mixing a primary and a secondary color. The secondary colors are, red-violet, blue-violet, blue-green, yellow-green, yellow-orange and red-orange. Color schemes are combinations of colors. There are many different types of color combinations, however, only four of the most basic are included here. They are: • Complementary colors • Analogous colors • Warm & Cool colors • Monochromatic colors Complementary Colors: are any two colors that are opposite each other on the color wheel. Analogous Colors: are any two colors that are adjacent to (or next to) each other on the color wheel. Warm & Cool Colors: warm colors are those colors that contain combinations of red and yellow. There are six. To help you remember what a warm color is, think of the sun or fire. Cool colors are those colors that contain green and blue. There are six of these too. -

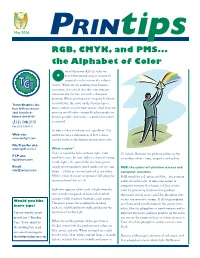

RGB, CMYK, and PMS... the Alphabet of Color Ne of the More Difficult Tasks We Face When Reproducing Your Printed Material Is to Be Certain the Color Is Ocorrect

May 2006 RGB, CMYK, and PMS... the Alphabet of Color ne of the more difficult tasks we face when reproducing your printed material is to be certain the color is Ocorrect. When we are printing your business stationery, it is critical that the color remains consistent for the first and each subsequent printing. When printing your company brochure or newsletter, the color on the finished piece TechneGraphics, Inc. Park 50 TechneCenter must conform to your expectations. And if we are 2002 Ford Circle printing in full color – especially photographs or Milford, OH 45150 food or people’s skin tones – a good color match (513) 248-2121 is essential. Fax (513) 248-5141 So why is color matching such a problem? The Web site: answer lies in a combination of how color is www.techgra.com created and how the human eye perceives color. File Transfer site: www.tgidirect.net What is color? Color is caused by light; without light, color 10 o’clock. Between the primary colors are the FTP site: would not exist. In turn, light is a form of energy. ftp.techgra.com secondary colors – cyan, magenta, and yellow. Visible light – the part of the electromagnetic Email: energy spectrum whose wavelengths our eyes can RGB: the colors of television screens and [email protected] detect – is blue at one end and red at the other. computer monitors All the colors in nature we perceive fall along the RGB stands for red, green and blue – the primary spectrum from blue to red. colors of visible light. A television screen or computer monitor that begins as black creates Light that appears white (such as light from the color by generating electrons that produce sun) is really composed of many colors which thousands of red, green, and blue phosphor dots become visible if passed through a glass prism.