Department of English and American Studies Not That Kind of Angel 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: Sept 09, 2020 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] PLEASE DOUBLECHECK ALL EVENTS, THINGS ARE STILL BE POSTPONED OR CANCELLED. SOMETIMES FACEBOOK WILL SAY CANCELLED YET WEBSITE STILL SHOWS REGULAR EVENT! JUNE 12-14 PA SCI-FI VALLEY CON 2020 POSTPONED TO JUNE 18-20, 2021 SF/Fantasy media https://www.scifivalleycon.com/ JUNE 12-14 Pitt THE LIVING DEAD WEEKEND POSTPONED TO NOV 6-8, 2020 Horror! http://www.thelivingdeadweekend.com/monroeville/ JUNE 12-14 NJ ANIME NEXT 2020 CANCELLED anime/manga/cosplay http://www.animenext.org/ JUNE 13-14 RI THE TERROR CON POSTPONED, no date set horror con https://www.theterrorcon.com/ JUNE 19-21 Phil WIZARD WORLD CANCELLED will return in 2021 media/comics/cosplay https://wizardworld.com/comiccon/philadelphia JUNE 19-21 T.O. INT'L FAN FESTIVAL TORONTO POSTPONED, no new date yet anime/gaming/comics https://toronto.ifanfes.com/ JUNE 19-21 Pitt MONSTER BASH CONFERENCE CANCELLED, see October event horror film/tv fans https://www.monsterbashnews.com/bash-June.html JUNE 20-21 Cinn SCI-CON 2020 CANCELLED will return in 2021 media/science/cosplay http://www.ctspromotions.com/currentshow/ JUNE 20-21 IN RAPTOR CON POSTPONED to Dec 12-13, 2020 anime/geek/media https://lind172.wixsite.com/rustyraptor/ JUNE 27-28 Buf LIL CON 7 POSTPONED, no new date announced yet http://lilconconvention.com/ JUNE 28 Buf PUNK ROCK FLEA MARKET & GEEK GARAGE -

Fine Italian Cuisine Nightly at Sapore Italiano in West Cape May • See Page 10 Stop in for Lunch Or Dinner Daily at the Red Br

FINE ITALIAN CUISINE NIGHTLY AT SAPORE ITALIANO STOP IN FOR LUNCH OR DINNER DAILY AT IN WEST CAPE MAY • SEE PAGE 10 THE RED BRICK ALE HOUSE • SEE PAGE 32 PAGE 2 PAGE 3 TV CHALLENGE SPORTS STUMPERS Indianapolis Colts By George Dickie 8) Who kicked a 32-yard field goal in the closing seconds that Questions: gave the Colts a 16-13 victory 1) In what year did the team over the Dallas Cowboys in Su- begin play in the NFL as the per Bowl V? Baltimore Colts? 9) In 1972, owner Carroll 2) In 1956, future Hall of Famer Rosenbloom “traded” the Colts Johnny Unitas joined the Colts and $3 million to Robert Irsay after being released by what NFL team? for what NFL franchise? 3) In the landmark 1958 NFL 10) In 1996, ‘98 and ‘99, the Championship Game, what Colts drafted three players in running back dove across the the first round who would be- goal line in the closing seconds come the cornerstones of the to give the Colts a 23-17 win team. Name them. over the New York Giants? 4) In 1965, what running back Answers: memorably filled in as emer- 1) 1953 gency quarterback when Unitas 2) Pittsburgh Steelers and backup Gary Cuozzo were 3) Alan Ameche lost to season-ending injuries? 4) Tom Matte 5) What future Hall of Famer 5) Don Shula was the Colts’ coach when 6) Art Schlichter they were upset by the New York Jets in Super Bowl III? 7) 1984 6) What Colts quarterback was 8) Jim O’Brien suspended for gambling in 9) The Los Angeles Rams 1983? 10) In chronological order, WR 7) In what year did the Colts Marvin Harrison, QB Peyton execute their infamous “mid- -

A Prophecy of the Christ!

A PROPHECY OF THE CHRIST! Gabriel’s Prophecy of the 70 Weeks (Daniel 9:24-27) Murray McLellan A Prophecy of the Christ! Gabriel’s Prophecy of the 70 Weeks (Daniel 9:24-27) Presented by Murray McLellan, an unworthy sinner upon whom grace unimaginable has been poured by the kindest of Kings. I do not claim to be, nor seek to be original in the following manuscript. I seek to magnify and exalt the Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world has been crucifed to me, and I to the world. Unto him belong the glory and the dominion forever and ever. Amen. “Seventy weeks are determined for your people and for your holy city, To fnish the transgression, To make an end of sins, To make reconciliation for iniquity, To bring in everlasting righteousness, To seal up vision and prophecy, And to anoint the Most Holy. Know therefore and understand, that from the going forth of the command to restore and build Jerusalem until Messiah the Prince, there shall be seven weeks and sixty-two weeks; The street shall be built again, and the wall, even in troublesome times. And after the sixty-two weeks Messiah shall be cut off, but not for Himself; And the people of the prince who is to come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary. The end of it shall be with a food, and till the end of the war desolations are determined. Then he shall confrm a covenant with many for one week; but in the middle of the week He shall bring an end to sacrifce and offering. -

Supernatural' Fandom As a Religion

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion Hannah Grobisen Claremont McKenna College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grobisen, Hannah, "The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2010. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2010 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College The Winchester Gospel The Supernatural Fandom as a Religion submitted to Professor Elizabeth Affuso and Professor Thomas Connelly by Hannah Grobisen for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 December 10, 2018 Table of Contents Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family………………………………………………………1 Saving People, Hunting Things. The Family Business: Messages, Values and Character Relationships that Foster a Community……………………………………………........9 There is No Singing in Supernatural: Fanfic, Fan Art and Fan Interpretation….......... 20 Gay Love Can Pierce Through the Veil of Death: The Importance of Slash Fiction….25 There’s Nothing More Dangerous than Some A-hole Who Thinks He’s on a Holy Mission: Toxic Misrepresentations of Fandom……………………………………......34 This is the End of All Things: Final Thoughts………………………………………...38 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………39 Important Characters List……………………………………………………………...41 Popular Ships…………………………………………………………………………..44 1 Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family Supernatural (WB/CW Network, 2005-) is the longest running continuous science fiction television show in America. -

Cons & Confusion

Cons & Confusion The almost accurate convention listing of the B.T.C.! We try to list every WHO event, and any SF event near Buffalo. updated: Feb 26, 2020 to add an SF/DW/Trek/Anime/etc. event; send information to: [email protected] 2020 DATE local EVENT NAME WHERE TYPE WEBSITE LINK FEB 26 - MAR 7 Buf MY HERO ACADEMIA: HEROS RISING North Park Theatre, 1428 Hertel, Buffalo anime film https://www.northparktheatre.org/ Cosplay contests for the first two nights! The anime phenomenon hits the big screen for Round 2! Posters and Japanese snacks at the stand. FEB 27 - MARCH 1 Bost PAX 2020 EAST Boston Conv Ctr, Boston, MA gaming event https://www.facebook.com/events/719029521929224/ FEB 28-29 Buf HARRY POTTER FILM & CONCERT Shea's Buffalo, 646 Main St, Buffalo, NY https://www.sheas.org/performances/ This concert features the film Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets™, on a giant screen, while the Buffalo Philharmonic performs John Williams’ unforgettable score. FEB 28 - MARCH 1 Chic CHICAGO COMIC & ENTERTAINMENT EXPO McCormick Place, Chicago, IL media & comics https://www.c2e2.com/ MATT SMITH (Sat/Sun), William Shatner, George Takei, Walter Koenig, Cat Staggs, Mike Perkins, Rod Reis, Terry Moore, Colleen Clinkenbeard, Josh Grelle, Steven Amell, Karl Urban, Rainbow Rowell, Faith Erin Hicks, Joe Hill, Hafsah Faizal, Karen Schneemann, Kat Leyh, Lily Williams, Lucy Knisley, Tricia Levenseller, Brina Palencia, Robbie Daymond, Ray Chase, Max Mittleman, Jason David Frank, Jim Lee, Jimmy Palmiotti, Amanda Conner, Cat Staggs, Terry Brooks, FEB -

Uses of the Bible in Contemporary Horror Films Mary Ann Beavis St

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha Journal of Religion & Film Volume 7 Article 2 Issue 2 October 2003 12-14-2016 "Angels Carrying Savage Weapons:" Uses of the Bible in Contemporary Horror Films Mary Ann Beavis St. Thomas More College, [email protected] Recommended Citation Beavis, Mary Ann (2016) ""Angels Carrying Savage Weapons:" Uses of the Bible in Contemporary Horror Films," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Angels Carrying Savage Weapons:" Uses of the Bible in Contemporary Horror Films Abstract As one of the great repositories of supernatural lore in Western culture, it is not surprising that the Bible is often featured in horror films. This paper will attempt to address this oversight by identifying, analyzing and classifying some uses of the Bible in horror films of the past quarter century. Some portrayals of the Bible which emerge from the examination of these films include: (1) the Bible as the divine word of truth with the power to drive away evil and banish fear; (2) the Bible as the source or inspiration of evil, obsession and insanity; (3) the Bible as the source of apocalyptic storylines; (4) the Bible as wrong or ineffectual; (5) the creation of non-existent apocrypha. -

Film Reviews

Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 15 (Autumn 2016) FILM REVIEWS (Please note that reviews may contain spoilers) He Never Died (Dir. by Jason Krawczyk) USA/Canada 2015 Alternate Ending Studios And the Lord said, ‘What have you done? The voice of your brother’s blood is crying to me from the ground. And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it shall no longer yield to you its strength; you shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth.’ –Genesis 4. 10-12 When it comes to entertainment, the only thing more commercial then sex is violence. And in the thousands of years since the Bible documented its first slaying, this seemingly insatiable desire to watch or read about homicide seems to remain unquenched. From Midsommer Murders (1997-present) to Memento (2000), and from Silence of the Lambs (1991) to Silent Witness (1996), there’s nothing more commercially profitable, it seems, then depicting a good murder. Tapping into primal and animalistic instincts, the representation of murder draws upon a sense that the human condition is to be fundamentally flawed, and suggests that such universal emotions as greed, jealousy, lust, and pride motivate a significant number of murders. The Old Testament figure of Cain, supposedly the first murderer (of his brother Abel), was forever cursed to ‘be a fugitive and a wanderer of the earth’ for all eternity.1 Cain’s story of fraternal betrayal and antagonism is one commonly represented in films such as Bloodline (2005), Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007), We Own the Night (2007), and the Broadway musical Blood Brothers (1983-present). -

The Paley Center for Media Announces the 8Th Annual Paleyfest Ny

THE PALEY CENTER FOR MEDIA ANNOUNCES THE 8TH ANNUAL PALEYFEST NY The 2020 Schedule to Showcase Cast and Creative Team Discussions from Television’s Most Acclaimed and Hottest Shows Including: All American, The Boys, Eli Roth’s History of Horror, Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, 20th Anniversary of Girlfriends, A Million Little Things, Rick and Morty, Supernatural, and The Undoing Talent Lineup Includes: Jensen Ackles, Samantha Bee, Susanne Bier, Alexander Calvert, Sarah Chalke, Misha Collins, Chace Crawford, Taye Diggs, Tracee Ellis Ross, Daniel Ezra, Karen Fukuhara, Hugh Grant, Dan Harmon, Nicole Kidman, Romany Malco, Allison Miller, Jared Padalecki, Chris Parnell, Eli Roth, Quentin Tarantino, Karl Urban, and Persia White Citi Returns as the Official Card and an Official Sponsor and Verizon Joins as an Official Sponsor Initial Slate of Programming Premieres on the Paley Channel on Verizon Media’s Yahoo Entertainment this Friday, October 23 at 8:00 pm EST/5:00 pm PST, with Additional Releases on Monday, October 26 at 8:00 pm EST/5:00 pm PST, and Tuesday, October 27 at 8:00 pm EST/5:00 pm PST Citi Cardmembers and Paley Center Members Can Preview Programs Beginning Today at 10:00 am EST/7:00 am PST Paley Center Members Have the Opportunity to Preview the Premiere Episode of The Undoing, a New Episode from Eli Roth’s History of Horror, and a Special Teaser from an Upcoming Episode of Supernatural New York, NY, October 20, 2020 – The Paley Center for Media announced today the start of the 8th annual PaleyFest NY. The premier television festival features some of the most acclaimed and hottest television shows and biggest stars, delighting fans with exclusive behind-the-scenes scoops, hilarious anecdotes, and breaking news stories. -

Saint Gabriel Archangel (Patron Saint of Communication Workers) Feast

“Do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you, whom you have from God, and that you are not your own?” 1 Corinthians 6:19 Saint Gabriel Archangel (patron saint of communication workers) Feast day: September 29, The name Gabriel means "man of God," or "God has shown himself mighty." It appears first in the prophesies of Daniel in the Old Testament. The angel announced to Daniel the prophecy of the seventy weeks. His name also occurs in the apocryphal book of Henoch. He was the angel who appeared to Zachariah to announce the birth of St. John the Baptizer. Finally, he announced to Mary that she would bear a Son Who would be conceived of the Holy Spirit, Son of the Most High, and Saviour of the world. The feast day is September 29th. St. Gabriel is the patron of communications workers. St. Isidore of Seville (patron saint of computer technicians, internet) Feast day: April 4 Isidore was probably born in Cartagena, Spain to Severianus and Theodora. His father belonged to a Hispano-Roman family of high social rank while his mother was of Visigothic origin and apparently, was distantly related to Visigothic royalty. His parents were members of an influential family who were instrumental in the political-religious maneuvering that converted the Visigothic kings from Arianism to Catholicism. The Catholic Church celebrates him and all his siblings as known saints: An elder brother, Saint Leander of Seville, immediately preceded Saint Isidore as Archbishop of Seville and, while in office, opposed king Liuvigild. -

Alyssa Milano Sorry Not Sorry Misha Collins Ep 117 AUTOMATED TRANSCRIPT – QUOTES MUST BE CHECKED AGAINST FINAL AUDIO FILE

Alyssa Milano Sorry Not Sorry Misha Collins Ep 117 AUTOMATED TRANSCRIPT – QUOTES MUST BE CHECKED AGAINST FINAL AUDIO FILE [00:00:00] AM: [00:00:00] Hi. Hi, I'm Alyssa Milano and this is Sorry Not Sorry.. [00:00:34] Hi everybody. I am so happy to be joined this week by my friend, Misha Collins. Misha is an actor who recently finished a long run starring in the hitch. Supernatural. [00:00:48] Clips (various): [00:00:48] Hi, this is Misha Collins from Supernatural. The moment I realized the show was a hit was when my son brought home a game of clue and it was supernatural [00:01:00] clue and it had my face on it. Did you have an irreverent megalomaniacal persona online, only? Are you an irreverent megalomaniacalperson? That's an excellent question. We have an unfortunatenew plague in society, which is cyber bullying. A lot of people find themselves victims. [00:01:22] MC: [00:01:22] Hi, I'm Misha. And I'm fighting to build more empathy in the world. Sorry, not sorry. [00:01:29] AM: [00:01:29] Misha, first of all, how long have we known each other? [00:01:32] MC: [00:01:32] That's a great question, Alyssa. I think the answer is on the order of 20 years. [00:01:39] AM: [00:01:39] Wow. [00:01:40] MC: [00:01:40] I mean, when we say known each other, I did an episode of Charmed, I don't even know. You probably don't remember this. -

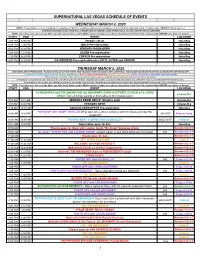

Supernatural Las Vegas Schedule of Events

SUPERNATURAL LAS VEGAS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS WEDNESDAY MARCH 4, 2020 NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS will be open too! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, SILVER, COPPER OR GA WEEKEND. NOTE: If you have solo, duo or group photo ops with Jared, Jensen, and/or Misha, please exchange your pdf for a hard ticket at the Photo Op exchange table BEFORE your photo op begins! START END EVENT LOCATION 2:00 PM 6:00 PM Vendors set-up Salsa Reg 6:00 PM 7:00 PM GOLD Pre-registration Salsa Reg 6:00 PM 8:30 PM VENDORS ROOM OPEN Salsa Reg 7:00 PM 7:10 PM SILVER Pre-registration Salsa Reg 7:10 PM 8:00 PM COPPER Pre-registration Salsa Reg 8:00 PM 8:30 PM GA WEEKEND Pre-registration plus GOLD, SILVER and COPPER Salsa Reg THURSDAY MARCH 5, 2020 *END TIMES ARE APPROXIMATE. PLEASE SHOW UP AT THE START TIME TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS ANYTHING! WE CANNOT GUARANTEE MISSED AUTOGRAPHS OR PHOTO OPS. Light Blue: Private meet & greets, Green: Autographs, Red: Theatre programming, Orange: VIP schedule, Purple: Photo ops, Dark Blue: Special Events Photo ops are on a first come, first served basis (unless you're a VIP or unless otherwise noted in the Photo op listing) Autographs for Gold/Silver are called row by row, then by those with their separate autographs, pre-purchased autographs are called first. -

Superwholock: the Face of the New Super-Fandom

SuperWhoLock: The Face of the New Super-Fandom ASHLEY JOYCE-NYACK Produced in Carlee Malemute’s ENC 1102 For almost every movie, TV show, book, or musical artist, there is a fan base that dedicates themselves to the entertainment they love. Fan bases—or fandoms—for TV shows, movies, and bands have been observed for many years, and it is accepted that they play a huge part in the success, or lack thereof, of an entertainment medium. Sometimes called a “cult following,” a fandom plays a large role in determining how popular a TV show is, and has even been powerful enough to bring shows back after their cancellation. Three of the shows with an influential “cult following” are BBC’s Sherlock and Doctor Who and the CW’s Supernatural. Each one of these shows have been positively affected by their fans, with NPR going as far as saying that one of the main reasons for Supernatural’s success is their fan base (Ulaby 1). One of the aspects of fandoms that has not been studied is when fandoms come together to form a super-fandom. This happened recently when the fan bases from Supernatural, Doctor Who, and Sherlock merged to form what is known as the SuperWhoLock fandom. This fandom has gained popularity over the past few years, and has garnered support on social media. A couple of the most talked about shows on the website Tumblr are Sherlock and Doctor Who, with popular actors Benedict Cumberbatch and Misha Collins being the most reblogged on Tumblr (Ulaby). This is a fairly new fan base, however, and has not been discussed as a whole, despite their impact on social media.