Unchained Melody Music Licensing in the Digital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Popular Love Songs

Popular Love Songs: After All – Multiple artists Amazed - Lonestar All For Love – Stevie Brock Almost Paradise – Ann Wilson & Mike Reno All My Life - Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Always and Forever – Luther Vandross Babe - Styx Because Of You – 98 Degrees Because You Loved Me – Celine Dion Best of My Love – The Eagles Candle In The Wind – Elton John Can't Take My Eyes off of You – Lauryn Hill Can't We Try – Vonda Shepard & Dan Hill Don't Know Much – Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Dreaming of You - Selena Emotion – The Bee Gees Endless Love – Lionel Richie & Diana Ross Even Now – Barry Manilow Every Breath You Take – The Police Everything I Own – Aaron Tippin Friends And Lovers – Gloria Loring & Carl Anderson Glory of Love – Peter Cetera Greatest Love of All – Whitney Houston Heaven Knows – Donna Summer & Brooklyn Dreams Hello – Lionel Richie Here I Am – Bryan Adams Honesty – Billly Joel Hopelessly Devoted – Olivia Newton-John How Do I Live – Trisha Yearwood I Can't Tell You Why – The Eagles I'd Love You to Want Me - Lobo I Just Fall in Love Again – Anne Murray I'll Always Love You – Dean Martin I Need You – Tim McGraw & Faith Hill In Your Eyes - Peter Gabriel It Might Be You – Stephen Bishop I've Never Been To Me - Charlene I Write The Songs – Barry Manilow I Will Survive – Gloria Gaynor Just Once – James Ingram Just When I Needed You Most – Dolly Parton Looking Through The Eyes of Love – Gene Pitney Lost in Your Eyes – Debbie Gibson Lost Without Your Love - Bread Love Will Keep Us Alive – The Eagles Mandy – Barry Manilow Making Love -

Eddie Mcpherson Big Dog Publishing

Eddie McPherson Big Dog Publishing The Jukebox Diner 2 Copyright © 2011, Eddie McPherson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Jukebox Diner is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and all of the countries covered by the Universal Copyright Convention and countries with which the United States has bilateral copyright relations including Canada, Mexico, Australia, and all nations of the United Kingdom. Copying or reproducing all or any part of this book in any manner is strictly forbidden by law. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or videotaping without written permission from the publisher. A royalty is due for every performance of this play whether admission is charged or not. A “performance” is any presentation in which an audience of any size is admitted. The name of the author must appear on all programs, printing, and advertising for the play. The program must also contain the following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Big Dog Publishing Company, Sarasota, FL.” All rights including professional, amateur, radio broadcasting, television, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved by Big Dog Publishing Company, www.BigDogPlays.com, to whom all inquiries should be addressed. Big Dog Publishing P.O. Box 1400 Tallevast, FL 34270 The Jukebox Diner 3 The Jukebox Diner COMEDY. The one-liners and puns never end in this hilarious comedy! Everyone in town is eager for Shelby, a big- time country-music star, to arrive from Nashville to attend Uncle Roy’s memorial service. -

“If Music Be the Food of Love, Play On

Magic Moments Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805-1871) was the most famous of all French magicians, for he is considered the world over as the father of modern conjuring. Jean’s père sent his eleven-year-old son up the Loire to the University of Orléans (not to be confused with UNO) to prepare for a career as a lawyer. But his son wanted to become a watchmaker like his dad, and these skills trained him in all things mechanical. The first magician to use electricity, Houdin was sent to Algeria in 1856 by the French government to combat the influence of the dervishes by duplicating their feats - a real whirlwind tour. His books helped explain the art of magic to countless aficionados: his autobiography (1857), Confidences d’un prestidigitateur (1859), and Les Secrets de la prestidigitation et de la magie (1868). One such devotee was arguably the most renowned illusionist and escape artist in history. Born in Hungary in 1874 as Erich Weiss, he adopted the name Harry Houdini as a teenager after having read Houdin’s autobiography. Performing twenty shows a day, the young wizard was soon taking home twelve dollars a week. Before long he was an international success, and he would bring this magic moxie to the Crescent City on more than one occasion. It was pouring rain that day in downtown New Orleans, November 17, 1907, when a crowd of nearly 10,000 people gathered along the wharves near the Canal Street ferry landing to witness Houdini triple- manacled for a death-defying plunge into the Mississippi River. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

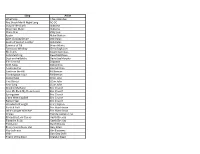

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

All Shook up As Sung by Elvis Presley

All Shook Up As sung by Elvis Presley Brass Band Arr.: Jirka Kadlec Adapt.: Bertrand Moren Elvis Presley / Otis Blackwell EMR 32315 st + 1 Full Score 2 1 B Trombone nd + 1 E Cornet 2 2 B Trombone + 5 Solo B Cornet 1 B Bass Trombone 1 Repiano B Cornet 2 B Euphonium nd 3 2 B Cornet 3 E Bass rd 3 3 B Cornet 3 B Bass 1 B Flugelhorn 1 Piano / Keyboard (optional) 2 Solo E Horn 1 Bass Guitar / String Bass (optional) 2 1st E Horn 1 Electric Guitar (optional) 2 2nd E Horn 1 Tambourine 2 1st B Baritone 1 Bongos 2 2nd B Baritone 1 Drum Set Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch DISCOGRAPHY Be Happy Track Titel / Title Time N° EMR N° EMR N° EMR N° (Komponist / Composer) Blasorchester Brass Band Big Band Concert Band 1 Hard Headed Woman (De Metruis) 2’36 EMR 12585A EMR 32310 EMR 12585B 2 Magnificat (Kadlec) 3’13 EMR 12638 EMR 32311 - 3 Sway (Molina / Ruiz) 3’18 EMR 12597A EMR 32312 EMR 12597B 4 My Way (Reveaux / François) 3’45 EMR 12150 EMR 32207 EMR 23569 5 Burning Love (Linde) 2’50 EMR 12590A EMR 32313 EMR 12590B 6 Fighting Trombones (Schiltknecht) 1’36 EMR 12547 EMR 32314 - 7 All Shook Up (Presley) 2’30 EMR 12575A EMR 32315 EMR 12575B 8 Be Happy (Reift) 2’45 EMR 12646 EMR 32316 - 9 Ocean Drive (Naulais) 3’50 EMR 12560 EMR 32317 EMR 31112 10 Hard To Say I’m Sorry (Cetera / Foster) 3’27 EMR 12636 EMR 32318 EMR 31223 11 Solitaire (Sedaka) 3’55 EMR 11405 EMR 32319 - 12 Rumba Del Amor (Reift) 2’46 EMR 12529 EMR 32320 - 13 Cubamania (Naulais) 4’44 EMR 12657 EMR 32321 EMR 31670 14 Rock And Roll Music (Berry) 2’37 EMR 12623A EMR 32322 EMR 12623B Zu bestellen bei • A commander chez • To be ordered from: Editions Marc Reift • Route du Golf 150 • CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) • Tel. -

View Song List

Song Artist What's Up 4 Non Blondes You Shook Me All Night Long AC-DC Song of the South Alabama Mountain Music Alabama Piano Man Billy Joel Austin Blake Shelton Like a Rolling Stone Bob Dylan Boots of Spanish Leather Bob Dylan Summer of '69 Bryan Adams Tennessee Whiskey Chris Stapleton Mr. Jones Counting Crows Ants Marching Dave Matthews Dust on the Bottle David Lee Murphy The General Dispatch Drift Away Dobie Gray American Pie Don McClain Castle on the Hill Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Rocket Man Elton John Tiny Dancer Elton John Your Song Elton John Drink In My Hand Eric Church Give Me Back My Hometown Eric Church Springsteen Eric Church Like a Wrecking Ball Eric Church Record Year Eric Church Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton Rock & Roll Eric Hutchinson OK It's Alright With Me Eric Hutchinson Cruise Florida Georgia Line Friends in Low Places Garth Brooks Thunder Rolls Garth Brooks The Dance Garth Brooks Every Storm Runs Out Gary Allan Hey Jealousy Gin Blossoms Slide Goo Goo Dolls Friend of the Devil Grateful Dead Let Her Cry Hootie and the Blowfish Bubble Toes Jack Johnson Flake Jack Johnson Barefoot Bluejean Night Jake Owen Carolina On My Mind James Taylor Fire and Rain James Taylor I Won't Give Up Jason Mraz Margaritaville Jimmy Buffett Leaving on a Jet Plane John Denver All of Me John Legend Jack & Diane John Mellancamp Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash Don't Stop Believing Journey Faithfully Journey Walking in Memphis Marc Cohn Sex and Candy Marcy's Playground 3am Matchbox 20 Unwell Matchbox 20 Bright Lights Matchbox 20 You Took The Words Right Out Of Meatloaf All About That Bass Megan Trainor Man In the Mirror Michael Jackson To Be With You Mr. -

Magic Moments in Dementia Care Services

Magic moments in dementia care services A storytelling approach to learning and development Learn Inspire Empower Enable Foreword Older Persons Commissioner As Chair of the 3 Nations Dementia Working Group, I have played a role in helping deliver a series of webinars some around the impact of COVID 19 on All professionals working across health people affected by Dementia. As well as being united against dementia we and care services should understand the now find ourselves united against COVID 19 as well, which has had a major challenges people living with dementia can effect on people living with dementia and their carers. We must learn from face, and the positive difference they can the experiences, with health and care workers and third sector organisations make by providing the right support and continuing to play an especially important role in supporting and protecting the creating Magic Moments. rights of people living with dementia during the crisis in the UK. Today learning from these stories to improve dementia care is more important than ever. We’ve seen the huge difference that moments of kindness have made to people’s It has been my pleasure to witness people with a diagnosis and their supporters lives throughout the pandemic, and this is overcome doubt, lack of experience and confidence to tell their stories that have something we need to hold onto and build changed hearts and minds with content that cannot be questioned, or motives upon as we move forward together. doubted as the testimony in this document illustrates . I would like to thank all of the people No one who reads these stories will not be affected by the purity and bravery living with dementia who overcame doubt, of the contributors all affected by Dementia. -

The Righteous Brothers by Jerry Bfay At

The Righteous Brothers B yJerry Bfayat •— —■ a d i o , w i t h o u t a d o u b t , is t h e m o s t i m p o r - and “Leaving It All lip to You,” which years later tant vehicle for a recording artist. How became a Number One hit for Dale & Grace. Two- many times did y o u turn on your radio part harmony was not unique then - but a pair of and hear a great song b y a great a r t i s t s ! white boys emulating the great black two-part-har Rmaybe Johnny Otis singing “Willie and thm e Hand on y sound? That w as new. Jive,” the Magnificent Men doing “Peace of Mind,” or For Bobby Hatfield and Bill M edley (bom a m onth the Soul Survivors performing “Expressway (To Your apart in 1940), it began separately. Both started Heart)” - not realizing these were white performers, singing at Orange County, California, clubs as ones who had the soul and the ability to sound teenagers. In the early 1960s, Bobby had his group, black? Conversely, did you ever lis the Variations, and Bill his, the ten to an artist like Ella Fitzgerald, Paramours. In 1962, Bobby’s group Carmen McRae or Nancy Wilson incorporated with the Paramours. and say to yourself, “Wow, what a One of their first big shows together fantastic performer,” and assume was at the Rendezvous Ballroom, in she was white? That’s the wonder Balboa, California, a famous haunt ful thing about music: The great during the big-band era. -

The First the First

PAGE 1 TTHHEE FFIIRRSSTT BBIIGG SSEESSSSIIOONN SSOONNGGBBOOOOKK 22001188 ALL THESE SONGS HAVE BEEN TAKEN WITH PERMISSION FROM WWW.DOCTORUKE .C OM IF YOU WANT TO KNOW HOW THEY GO THEN EACH SONG CAN BE HEARD ON DR UKE'S WEBSITE UPTON UKULELE FESTI VAL 2018 PAGE 2 UPTON LAZ Y RIVER 4/4 1…2…1234 UPTON lazy river by the old mill-run, that lazy, lazy river in the noonday sun . Linger in the shade of a kind old tree; throw away your troubles, dream a dream with me UPTON lazy river where the robin’s song a-wakes a bright new morning, we can loaf along . Blue skies up a-bove, everyone’s in love; UPTON lazy river, how happy we will be, UPTON a lazy river……..without a paddle , UPTON.... lazy river………. with me UPTON UKULELE FESTI VAL 2018 THE CAT CAME BACK PAGE 3 4/4 1...2...1234 Intro: Dm C / Bb A7 / (X2) Dm C Bb A7 Dm C Bb A7 Old Mister Johnson had troubles of his own. He had a yellow cat who wouldn't leave its home; Dm C Bb A7 Dm C Bb A7 He tried and he tried to give the cat a-way, he gave it to a man who was goin' far a-way. Dm C Bb A7 But the cat came back the very next day, Dm C Bb A7 The cat came back, they thought he was a goner Dm C Bb A7 Dm C Bb A7#5 But the cat came back, he just couldn't stay a-way. -

Big Blast & the Party Masters

BIG BLAST & THE PARTY MASTERS 2018 Song List ● Aretha Franklin - Freeway of Love, Dr. Feelgood, Rock Steady, Chain of Fools, Respect, Hello CURRENT HITS Sunshine, Baby I Love You ● Average White Band - Pick Up the Pieces ● B-52's - Love Shack - KB & Valerie+A48 ● Beatles - I Want to Hold Your Hand, All You Need ● 5 Seconds of Summer - She Looks So Perfect is Love, Come Together, Birthday, In My Life, I ● Ariana Grande - Problem (feat. Iggy Azalea), Will Break Free ● Beyoncé & Destiny's Child - Crazy in Love, Déjà ● Aviici - Wake Me Up Vu, Survivor, Halo, Love On Top, Irreplaceable, ● Bruno Mars - Treasure, Locked Out of Heaven Single Ladies(Put a Ring On it) ● Capital Cities - Safe and Sound ● Black Eyed Peas - Let's Get it Started, Boom ● Ed Sheeran - Sing(feat. Pharrell Williams), Boom Pow, Hey Mama, Imma Be, I Gotta Feeling Thinking Out Loud ● The Bee Gees - Stayin' Alive, Emotions, How Deep ● Ellie Goulding - Burn Is You Love ● Fall Out Boy - Centuries ● Bill Withers - Use Me, Lovely Day ● J Lo - Dance Again (feat. Pitbull), On the Floor ● The Blues Brothers - Everybody Needs ● John Legend - All of Me Somebody, Minnie the Moocher, Jailhouse Rock, ● Iggy Azalea - I'm So Fancy Sweet Home Chicago, Gimme Some Lovin' ● Jessie J - Bang Bang(Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj) ● Bobby Brown - My Prerogative ● Justin Timberlake - Suit and Tie ● Brass Construction - L-O-V-E - U ● Lil' Jon Z & DJ Snake - Turn Down for What ● The Brothers Johnson - Stomp! ● Lorde - Royals ● Brittany Spears - Slave 4 U, Till the World Ends, ● Macklemore and Ryan Lewis - Can't Hold Us Hit Me Baby One More Time ● Maroon 5 - Sugar, Animals ● Bruno Mars - Just the Way You Are ● Mark Ronson - Uptown Funk (feat. -

Contemporary IdiomsTM Voice Level 6

Contemporary IdiomsTM Voice Level 6 Length of examination: 30 minutes Examination Fee: Please consult our website for the schedule of fees: www.conservatorycanada.ca Corequisite: Successful completion of the Theory 2 written examination is required for the awarding of the Level 6 certificate. REQUIREMENTS & MARKING Requirements Total Marks Piece 1 12 Repertoire Piece 2 12 4 pieces of contrasting styles Piece 3 12 Piece 4 12 Technique Listed exercises 16 Sight Reading Rhythm (3) Singing (7) 10 Aural Tests Sing back (4) Chords (3) Intervals (3) 10 Improvisation Improv Exercise or Own Choice Piece 8 Background Information 8 Total Possible Marks 100 *One bonus mark will be awarded for including a repertoire piece by a Canadian composer CONSERVATORY CANADA ™ Level 6 July 2020 1 REPERTOIRE ● Candidates are required to perform FOUR pieces from the Repertoire List, contrasting in key, tempo, mood and subject. Your choices must include at least two different composers. All pieces must be sung from memory and may be transposed to suit the compass of the candidate's voice. ● One of the repertoire pieces may be chosen from any level higher. ● The Repertoire List is updated regularly to include newer music, and is available for download on the CI Voice page. ● Due to time and space constraints, Musical Theatre selections may not be performed with elaborate choreography, costumes, props, or dance breaks. ● The use of a microphone is optional at this level, and must be provided by the student, along with appropriate sound equipment (speaker, amplifier) if used. ● Repertoire that is currently not on our lists can be used as Repertoire pieces with prior approval. -

Quality Hill Be-Bops Into 1950S Doo-Wop Era

Quality Hill be-bops into 1950s Doo-wop Era By Bob Evans Larry Levenson & Quality Hill Playhouse Quality Hill Playhouse, the only venue of its kind in the Kansas City metro generally builds shows around the Broadway music of the Great American Songbook, but in a radical, fun, spirited departure from the norm, “Unchained Melody” brings the focus to the AM radio top 40 charts of the 1950s as that era ushered in the Doo-Wop sounds of the younger generation. T Larry Levenson and Quality Hill Playhouse he music people listened to changed from the Big Bands of the 1940s and the solo performers that survived the WWII aftermath of the Big Bands to a new, fresh sound that featured younger singers and songwriters. Coupled with “Hillbilly” music, and “Rhythm and Blues” the new popular music became known as do- wop. According to J. Kent Barnhart, artistic director of QHP, the music contains distinguished cords, melodies, and syncopations far from the sounds of the Big Bands. The Bobby Soxers who swooned to Frank Sinatra were replaced by the screaming fans that adored the gyrations of a new king, Elvis Presley. Doo-Wop had arrived. Larry Levenson & Quality Hill Playhouse The Billboard Top 40 charts ruled the USA as the new sounds exploded over the airways. Songs like “Rock Around the Clock,” “Sha-boom,” “Cry,” “Hound Dog,” and many more filled the airways. “Take a romantic trip down memory lane in this cabaret revue featuring the unique American sound known as “doo-wop,” Quality Hill advertising said. “Doo-wop groups dominated the radio airwaves for over a decade, thanks to their songs’ simple melodies, tight harmonies, and frequent themes of love and relationships.