The Use of Executive Orders in Wisconsin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report

City of Madison, Wisconsin Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report By Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB, Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA and Robert Short, Associate AIA Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 and Jason Tish Archetype Historic Property Consultants 2714 Lafollette Avenue Madison, Wisconsin 53704 Project Sponsoring Agency City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development 215 Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard Madison, Wisconsin 53703 2017-2020 Acknowledgments The activity that is the subject of this survey report has been financed with local funds from the City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development. The contents and opinions contained in this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the city, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the City of Madison. The authors would like to thank the following persons or organizations for their assistance in completing this project: City of Madison Richard B. Arnesen Satya Rhodes-Conway, Mayor Patrick W. Heck, Alder Heather Stouder, Planning Division Director Joy W. Huntington Bill Fruhling, AICP, Principal Planner Jason N. Ilstrup Heather Bailey, Preservation Planner Eli B. Judge Amy L. Scanlon, Former Preservation Planner Arvina Martin, Alder Oscar Mireles Marsha A. Rummel, Alder (former member) City of Madison Muriel Simms Landmarks Commission Christina Slattery Anna Andrzejewski, Chair May Choua Thao Richard B. Arnesen Sheri Carter, Alder (former member) Elizabeth Banks Sergio Gonzalez (former member) Katie Kaliszewski Ledell Zellers, Alder (former member) Arvina Martin, Alder David W.J. McLean Maurice D. Taylor Others Lon Hill (former member) Tanika Apaloo Stuart Levitan (former member) Andrea Arenas Marsha A. -

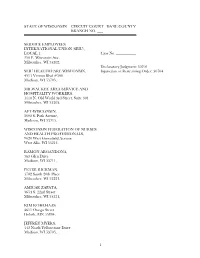

SEIU), LOCAL 1, Case No

STATE OF WISCONSIN CIRCUIT COURT DANE COUNTY BRANCH NO. ___ SERVICE EMPLOYEES INTERNATIONAL UNION (SEIU), LOCAL 1, Case No. __________ 250 E. Wisconsin Ave, Milwaukee, WI 53202, Declaratory Judgment: 30701 SEIU HEALTHCARE WISCONSIN, Injunction or Restraining Order: 30704 4513 Vernon Blvd #300 Madison, WI 53705, MILWAUKEE AREA SERVICE AND HOSPITALITY WORKERS, 1110 N. Old World 3rd Street, Suite 304 Milwaukee, WI 53203, AFT-WISCONSIN, 1602 S. Park Avenue, Madison, WI 53715, WISCONSIN FEDERATION OF NURSES AND HEALTH PROFESSIONALS, 9620 West Greenfield Avenue, West Allis, WI 53214, RAMON ARGANDONA, 563 Glen Drive Madison, WI 53711, PETER RICKMAN, 3702 South 20th Place Milwaukee, WI 53221, AMICAR ZAPATA, 3654 S. 22nd Street Milwaukee, WI 53221, KIM KOHLHAAS, 4611 Otsego Street Duluth, MN 55804, JEFFREY MYERS, 342 North Yellowstone Drive Madison, WI 53705, 1 ANDREW FELT, 3641 Jordan Lane, Stevens Point, WI 54481, CANDICE OWLEY, 2785 South Delaware Avenue, Milwaukee, WI 53207, CONNIE SMITH, 4049 South 5th Place, Milwaukee, WI 53207, JANET BEWLEY, 60995 Pike River Road, Mason, WI 54856, Plaintiffs, v. ROBIN VOS, in his official capacity as Wisconsin Assembly Speaker, 321 State St, Madison, WI 53702, ROGER ROTH, in his official capacity as Wisconsin Senate President, State Capitol—Room 220 South Madison, WI 53707 JIM STEINEKE, in his official capacity as Wisconsin Assembly Majority Leader, 2 E Main St, Madison, WI 53703 SCOTT FITZGERALD, in his official capacity as Wisconsin Senate Majority Leader, 206 State St, Madison, WI 53702 JOSH KAUL, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the State of Wisconsin 7 W Main St, Madison, WI 53703, 2 TONY EVERS, in his official capacity as Governor of the State of Wisconsin, State Capitol—Room 115 East Madison, WI 53702, Defendants. -

John E Holmes: an Early Wisconsin Leader

Wisconsin Magazine of History TIte Anti-McCarthy Camf^aign in Wisconsin, 1951—1952 MICHAEL O'BRIEN Wisconsin Labor and the Campaign of 1952 DAVID M. OSHINSKY Foreign Aid Under Wrap: The Point Four Program THOMAS G. PATERSON John E. Holmes; An Early Wisconsin Leader STUART M. RICH Reminiscences of Life Among tIte Chif^pxva: Part Four BENJAMIN G. ARMSTRONG Published by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin / Vol. 56, No. 2 / Winter, 1972-1973 THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN JAMES MORTON SMITH, Director Officers E. DAVID CRONON, President GEORGE BANTA, JR., Honorary Vice-President JOHN C. GEILFUSS, First Vice-President E. E. HOMSTAD, Treasurer HOWARD W. MEAD, Second Vice-President JAMES MORTON SMITH, Secretary Board of Curators Ex Officio PATRICK J. LUCEY, Governor of the State CHARLES P. SMITH, State Treasurer ROBERT C. ZIMMERMAN, Secretary of State JOHN C. WEAVER, President of the University MRS. GORDON R. WALKER, President of the Women's Auxiliary Term Expires, 1973 THOMAS H. BARLAND MRS. RAYMOND J. KOLTES FREDERICK I. OLSON DONALD C. SLIGHTER Eau Claire Madison Wauwatosa Milwaukee E. E. HOMSTAD CHARLES R. MCCALLUM F. HARWOOD ORBISON DR. LOUIS C. SMITH Black River Falls Hubertus Appleton Lancaster MRS. EovifARD C. JONES HOWARD W. MEAD NATHAN S. HEFFERNAN ROBERT S. ZIGMAN Fort Atkinson Madison Madison Milwaukee Term Expires, 1974 ROGER E. AXTELL PAUL E. HASSETT ROBERT B. L. MURPHY MILO K. SWANTON Janesville Madison Madison Madison HORACE M. BENSTEAD WILLIAM HUFFMAN MRS. WM. H. L. SMYTHE CEDRIC A. Vic Racine Wisconsin Rapids Milwaukee Rhinelander REED COLEMAN WARREN P. KNOWLES WILLIAM F. STARK CLARK WILKINSON Madison Madison Nashotah Baraboo Term Expires, 1975 E. -

THE WISCONSIN SURVEY - Spring 2002

THE WISCONSIN SURVEY - Spring 2002 http://www.snc.edu/survey/report_twss02.html THE WISCONSIN SURVEY Survey Information: Survey Sponsors: Wisconsin Public Radio and St. Norbert College Survey Methodology: Random statewide telephone survey of Wisconsin residents. The random digit dial method selects for both listed and unlisted phone numbers. Eight attempts were made on each telephone number randomly selected to reach an adult in the household. Survey History: the survey has been conducted biannually since 1984. Data Collection Time Period: 3/20/02 - 4/7/02 N = 407 Error Rate: 4.864% at the 95% confidence level. The margin of error will be larger for subgroups. Key Findings: According to the Wisconsin Public Radio - St. Norbert College Survey Center poll, if the general election were held today, Governer McCallum would be ahead of Democratic or third party contenders in hypothetical election pairings of candidates. However, in the race between McCallum and Doyle, the percentage lead McCallum has over Doyle is within the margin of error of the survey. In other words, there is no statistically significant difference between the two candidates. In the hypothetical pairings of McCallum against the other Democratic Party candidates, McCallum appears to be well ahead. Another indicator of sentiment for the candidates is the "favorable" and "unfavorable" ratings. Here, Doyle rates the highest, with 36% of respondents saying they had a favorable impression of him, compared to McCallum's 31%. Similarly, only 18% of respondents said they had an unfavorable opinion of Doyle compared to 35% of respondents saying they had an unfavorable opinion of McCallum. So, why is there no significant difference in the polls between McCallum and Doyle when Doyle seems to be more highly esteemed? More people have not heard of Doyle than McCallum and those who have not heard of Doyle are likely to vote for McCallum. -

Harassment Case Hearing Delayed Regent Challenged by Students On

THE immMmmmmUW M*;-* ,^ OST Tuesday, October 14, 1986 The University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee Volume 31, Number 11 Harassment case hearing delayed Former swim coach says UWM, regents, named in $1 million sex harassment suit tional injuries. the Occupational Therapy Prog he will sue University by Michael Szymanski Frederick Pairent, dean of the ram, and James McPherson, a School of Allied Health Profes professor in the School of Allied 'Housecleaning' blamed for loss of job ormer UWM Assistant Pro sions, and former assistant dean, Health Professions, are listed in fessor Katherine King has Stephen Sonstein, are also the complaint as defendants. by Michael Mathias Ffiled a lawsuit in federal named in the complaint. The The case, which was initially court demanding a jury trial a- complaint accuses Sonstein of scheduled to open Monday, has ormer UWM swim coach Fred Russell said Monday he gainst the UW System's Board of sexually harassing King during been postponed and is being plans to file a lawsuit against the University to contest what Regents for alleged sex discrimi the 1980-81 academic year. rescheduled at the request of he calls a violation of his contract that eventually led to his nation, sexual harassment and King left the University in 1983 Federal Judge John Reynolds. F resignation last July. damage to her professional repu due to an illness. King said the trial will convene Russell, who was named last year's coach of the year by the tation and career, according to According to the complaint, soon. NAIA and had been UWM's swim coach for the past 10 years, the court complaint. -

Henry Maier, the Wisconsin Alliance of Cities, and the Movement to Modify Wisconsin's State Shared Revenues

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2020 Redistributing Resources: Henry Maier, the Wisconsin Alliance of Cities, and the Movement to Modify Wisconsin's State Shared Revenues Samantha J. Fleischman University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fleischman, Samantha J., "Redistributing Resources: Henry Maier, the Wisconsin Alliance of Cities, and the Movement to Modify Wisconsin's State Shared Revenues" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 2498. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/2498 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REDISTRIBUTING RESOURCES: HENRY MAIER, THE WISCONSIN ALLIANCE OF CITIES, AND THE MOVEMENT TO MODIFY WISCONSIN’S STATE SHARED REVENUES by Samantha Fleischman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2020 ABSTRACT REDISTRIBUTING RESOURCES: HENRY MAIER, THE WISCONSIN ALLIANCE OF CITIES, AND THE MOVEMENT TO MODIFY WISCONSIN’S STATE SHARED REVENUES by Samantha Fleischman The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2020 Under the Supervision of Professor Amanda Seligman During the 1960s, the City of Milwaukee was enduring fiscal distress. Mayor of Milwaukee, Henry Maier, turned to the State of Wisconsin to modify the state shared revenues formula as a method to increase funding for central cities. Maier created the Wisconsin Alliance of Cities, which was comprised of mayors throughout the state, in order to gain the support needed to pass formula changes through legislation. -

Wisconsin in La Crosse

CONTENTS Wisconsin History Timeline. 3 Preface and Acknowledgments. 4 SPIRIT OF David J. Marcou Birth of the Republican Party . 5 Former Governor Lee S. Dreyfus Rebirth of the Democratic Party . 6 Former Governor Patrick J. Lucey WISCONSIN On Wisconsin! . 7 A Historical Photo-Essay Governor James Doyle Wisconsin in the World . 8 of the Badger State 1 David J. Marcou Edited by David J. Marcou We Are Wisconsin . 18 for the American Writers and Photographers Alliance, 2 Professor John Sharpless with Prologue by Former Governor Lee S. Dreyfus, Introduction by Former Governor Patrick J. Lucey, Wisconsin’s Natural Heritage . 26 Foreword by Governor James Doyle, 3 Jim Solberg and Technical Advice by Steve Kiedrowski Portraits and Wisconsin . 36 4 Dale Barclay Athletes, Artists, and Workers. 44 5 Steve Kiedrowski & David J. Marcou Faith in Wisconsin . 54 6 Fr. Bernard McGarty Wisconsinites Who Serve. 62 7 Daniel J. Marcou Communities and Families . 72 8 tamara Horstman-Riphahn & Ronald Roshon, Ph.D. Wisconsin in La Crosse . 80 9 Anita T. Doering Wisconsin in America . 90 10 Roberta Stevens America’s Dairyland. 98 11 Patrick Slattery Health, Education & Philanthropy. 108 12 Kelly Weber Firsts and Bests. 116 13 Nelda Liebig Fests, Fairs, and Fun . 126 14 Terry Rochester Seasons and Metaphors of Life. 134 15 Karen K. List Building Bridges of Destiny . 144 Yvonne Klinkenberg SW book final 1 5/22/05, 4:51 PM Spirit of Wisconsin: A Historical Photo-Essay of the Badger State Copyright © 2005—for entire book: David J. Marcou and Matthew A. Marcou; for individual creations included in/on this book: individual creators. -

National Governors' Association Annual Meeting 1977

Proceedings OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEETING 1977 SIXTY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING Detroit. Michigan September 7-9, 1977 National Governors' Association Hall of the States 444 North Capitol Street Washington. D.C. 20001 Price: $10.00 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 12-29056 ©1978 by the National Governors' Association, Washington, D.C. Permission to quote from or to reproduce materials in this publication is granted when due acknowledgment is made. Printed in the United Stales of America CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Standing Committee Rosters vii Attendance ' ix Guest Speakers x Program xi OPENING PLENARY SESSION Welcoming Remarks, Governor William G. Milliken and Mayor Coleman Young ' I National Welfare Reform: President Carter's Proposals 5 The State Role in Economic Growth and Development 18 The Report of the Committee on New Directions 35 SECOND PLENARY SESSION Greetings, Dr. Bernhard Vogel 41 Remarks, Ambassador to Mexico Patrick J. Lucey 44 Potential Fuel Shortages in the Coming Winter: Proposals for Action 45 State and Federal Disaster Assistance: Proposals for an Improved System 52 State-Federal Initiatives for Community Revitalization 55 CLOSING PLENARY SESSION Overcoming Roadblocks to Federal Aid Administration: President Carter's Proposals 63 Reports of the Standing Committees and Voting on Proposed Policy Positions 69 Criminal Justice and Public Protection 69 Transportation, Commerce, and Technology 71 Natural Resources and Environmental Management 82 Human Resources 84 Executive Management and Fiscal Affairs 92 Community and Economic Development 98 Salute to Governors Leaving Office 99 Report of the Nominating Committee 100 Election of the New Chairman and Executive Committee 100 Remarks by the New Chairman 100 Adjournment 100 iii APPENDIXES I Roster of Governors 102 II. -

Blistnnsin ~Riefs from the Reference Bureau

Legislative ;Blistnnsin ~riefs from the Reference Bureau Brief 79-3 April 1979 CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT TO BE CONSIDERED BY THE WISCONSIN ELECTORATE APRIL 3, 1979 I. INTRODUCTION Only one proposed amendment to the Wisconsin Constitution will be submitted to the Wisconsin electorate for ratification at the election on April 3, 1979. This constitutional amendment, appearing on the ballot in the form of four questions, provides for gubernatorial succession, filling a vacancy in the office of lieutenant governor, selection of the Senate's presiding officer from among the members of the Senate, and a revision of several constitutional sections to make the text more understandable. Amending the Wisconsin Constitution requires the adoption of a proposed amendment by two successive sessions of the legislature and ratification of an amendment by the voters. A proposed amendment is introduced in the legislature in the form of a joint resolution. This step is called "first consideration". If the joint resolution is adopted by both houses, a new joint resolution embodying an identical text may be introduced on "second consideration" in the following session of the legislature. Joint resolutions are not submitted to the governor for approval. Sections Affected Joint Resolutions Subject Art. IV, Sec, 9; Art. Proposed by 1977 SJR Provides for gubernatorial V, Secs. 1,1m,1n, 7 51 (Enrolled JR 32) succession, filling a and 8; Art. VI, Secs. (1st Consideration); vacancy in the off ice 1, 1m, 1n, and 1p; Art. 19 7 9 SJR 1 (Enrolled of lieutenant governor, XIII, Sec. 10 JR 3) (2nd Consider selection of Senate's ation) presiding officer, and miscellaneous revisions to clarify the text. -

Verbatim Minutes of the Regular Meeting

MINUTES OF THE REGULAR MEETING of the BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN SYSTEM Madison, Wisconsin Held in room 1820 Van Hise Hall Friday, September 7, 2001 9:00 a.m. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES ................................................................................... 1 REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD ..................................................... 1 Resolution of Appreciation to the Governor and Legislature ................................. 2 ADMISSIONS POLICY ........................................................................................................ 4 TH TH REPORT ON THE JULY 11 AND SEPTEMBER 5 MEETINGS OF THE HOSPITAL AUTHORITY BOARD ............................................................................................................................. 4 TH REPORT ON THE JULY 25 MEETING OF THE WISCONSIN TECHNICAL COLLEGE SYSTEM BOARD ............................................................................................................................. 5 TH REPORT ON THE JULY 20 MEETING OF THE HIGHER EDUCATIONAL AIDS BOARD .......... 5 REPORT ON GOVERNMENT MATTERS ............................................................................... 5 RESOLUTION COMMENDING PROFESSOR JAMES THOMSON, HIS COLLEAGUES AND THE WISCONSIN ALUMNI RESEARCH FOUNDATION FOR STEM CELL RESEARCH ACHIEVEMENT. ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Stem Cell Research Achievements ........................................................................ -

Wisconsin Magazine ^ of History

•im^i^j;^^ y- .>?^s^%^^?&i'V\ ::rr^Q^fi^mm^mi^Mmti'^.^ Wisconsin Magazine ^ of History Athletics in the Wisconsin State University System, 1867—1913 RONALD A. SMITH An Unrecopvized Father Marquette Letter? RAPHAEL N. HAMILTON The Wisconsin l^ational Guard in the Milwaukee Riots of 1886 JERRY M. COOPER The Truman Presidency: Trial and Error ATHAN THEOHARIS Proceedings of the One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Annual Meeting Published by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin / Vol. 55, No. 1 / Autumn, 1971 THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN JAMES MORTON SMITH, Director Officers E. DAVID CRONON, President GEORGE BANTA, JR., Honorary Vice-President JOHN C. GEILFUSS, First Vice-President E. E. HoMSTAD, Treasurer HOWARD W. MEAD, Second Vice-President JAMES MORTON SMITH, Secretary Board of Curators Ex-Officio PATRICK J. LUCEY, Governor of the State CHARLES P. SMITH, State Treasurer ROBERT C. ZIMMERMAN, Secretary of State JOHN C. WEAVER, President of the University MRS. GEORGE SWART, President of the Women's Auxiliary Term Expires, 1972 E. DAVID CRONON ROBERT A. GEHRKE BEN GUTHRIE J. WARD RECTOR Madison Ripon Lac du Flambeau Milwaukee SCOTT M. CUTLIP JOHN C. GEILFUSS MRS. R. L. HARTZELL CLIFFORD D. SWANSON Madison Milwaukee Grantsburg Stevens Point MRS. ROBERT E. FRIEND MRS. HOWARD T. GREENE ROBERT H. IRRMANN Hartland Milwaukee Beloit Term Expires, 1973 THOMAS H. BARLAND MRS. RAYMOND J. KOLTES FREDERICK I. OLSON DR. LOUIS C. SMITH Eau Claire Madison Wauwatosa Lancaster E. E. HOMSTAD CHARLES R. MCCALLUM F. HARWOOD ORBISON ROBERT S. ZIGMAN Black River Falls Hubertus Appleton Milwaukee MRS. EDWARD C. JONES HOWARD W. -

2011-2012 Wisconsin Blue Book: Executive Branch

Executive 6 Branch The executive branch: profile of the executive branch and descriptions of constitutional offices, departments, independent agencies, state authorities, regional agencies, and interstate agencies and compacts 1911 Blue Book: State Capitol 310 WISCONSIN BLUE BOOK 2011 – 2012 ELECTIVE CONSTITUTIONAL EXECUTIVE STATE OFFICERS Annual Office Officer/Party Residence1 Term Expires Salary2 Governor Scott Walker (Republican) Milwaukee January 5, 2015 $144,423 Lieutenant Governor Rebecca Kleefisch (Republican) Oconomowoc January 5, 2015 76,261 Secretary of State Douglas J. La Follette (Democrat) Kenosha January 5, 2015 68,556 State Treasurer Kurt W. Schuller (Republican) Milwaukee January 5, 2015 68,556 Attorney General J.B. Van Hollen (Republican) Waunakee January 5, 2015 140,147 Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Evers (nonpartisan office) Madison July 1, 2013 120,111 1Residence when originally elected. 2Annual salary as established for term of office by the Wisconsin Legislature. Sources: 2009-2010 Wisconsin Statutes; Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, Wisconsin Brief 10-8, Salaries of State Elected Officials, December 2010. The State Capitol impresses regardless of season. (Steve Miller, LRB) 311 EXECUTIVE BRANCH A PROFILE OF THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH Structure of the Executive Branch The structure of Wisconsin state government is based on a separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The legislative branch sets broad policy and es- tablishes the general structures and regulations for carrying them out. The executive branch administers the programs and policies, while the judicial branch is responsible for adjudicating any conflicts that may arise from the interpretation or application of the laws. Constitutional Officers. The executive branch includes the state’s six constitutional officers – the governor, lieutenant governor, secretary of state, state treasurer, attorney general, and state superintendent of public instruction.