Structure and Interpretation of Alan Turing's Imitation Game / Bernardo Nunes Gonçalves ; Orientador Edelcio G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2016 Apr 28th, 9:00 AM - 10:15 AM To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology? Hayley A. LeBlanc Sunset High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y LeBlanc, Hayley A., "To What Extent Did British Advancements in Cryptanalysis During World War II Influence the Development of Computer Technology?" (2016). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2016/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. To what extent did British advancements in cryptanalysis during World War 2 influence the development of computer technology? Hayley LeBlanc 1936 words 1 Table of Contents Section A: Plan of Investigation…………………………………………………………………..3 Section B: Summary of Evidence………………………………………………………………....4 Section C: Evaluation of Sources…………………………………………………………………6 Section D: Analysis………………………………………………………………………………..7 Section E: Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………10 Section F: List of Sources………………………………………………………………………..11 Appendix A: Explanation of the Enigma Machine……………………………………….……...13 Appendix B: Glossary of Cryptology Terms.…………………………………………………....16 2 Section A: Plan of Investigation This investigation will focus on the advancements made in the field of computing by British codebreakers working on German ciphers during World War 2 (19391945). -

A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons 1926 to Circa 1990

A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons 1926 to circa 1990 TT King TT King A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons, 1926 to circa 1990 TT King Society Archivist 1 A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons, 1926 to circa 1990 © 2017 The Society of British Neurological Surgeons First edition printed in 2017 in the United Kingdom. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permis- sion of The Society of British Neurological Surgeons. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the infor- mation contained in this publication, no guarantee can be given that all errors and omissions have been excluded. No responsibility for loss oc- casioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by The Society of British Neurological Surgeons or the author. Published by The Society of British Neurological Surgeons 35–43 Lincoln’s Inn Fields London WC2A 3PE www.sbns.org.uk Printed in the United Kingdom by Latimer Trend EDIT, DESIGN AND TYPESET Polymath Publishing www.polymathpubs.co.uk 2 The author wishes to express his gratitude to Philip van Hille and Matthew Whitaker of Polymath Publishing for bringing this to publication and to the British Orthopaedic Association for their help. 3 A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons 4 Contents Foreword -

APA Newsletter on Philosophy and Computers, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Spring

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Philosophy and Computers SPRING 2019 VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 2 FEATURED ARTICLE Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot Turing’s Mystery Machine ARTICLES Igor Aleksander Systems with “Subjective Feelings”: The Logic of Conscious Machines Magnus Johnsson Conscious Machine Perception Stefan Lorenz Sorgner Transhumanism: The Best Minds of Our Generation Are Needed for Shaping Our Future PHILOSOPHICAL CARTOON Riccardo Manzotti What and Where Are Colors? COMMITTEE NOTES Marcello Guarini Note from the Chair Peter Boltuc Note from the Editor Adam Briggle, Sky Croeser, Shannon Vallor, D. E. Wittkower A New Direction in Supporting Scholarship on Philosophy and Computers: The Journal of Sociotechnical Critique CALL FOR PAPERS VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 2 SPRING 2019 © 2019 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and Computers PETER BOLTUC, EDITOR VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 2 | SPRING 2019 Polanyi’s? A machine that—although “quite a simple” one— FEATURED ARTICLE thwarted attempts to analyze it? Turing’s Mystery Machine A “SIMPLE MACHINE” Turing again mentioned a simple machine with an Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot undiscoverable program in his 1950 article “Computing UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY, CHRISTCHURCH, NZ Machinery and Intelligence” (published in Mind). He was arguing against the proposition that “given a discrete- state machine it should certainly be possible to discover ABSTRACT by observation sufficient about it to predict its future This is a detective story. The starting-point is a philosophical behaviour, and this within a reasonable time, say a thousand discussion in 1949, where Alan Turing mentioned a machine years.”3 This “does not seem to be the case,” he said, and whose program, he said, would in practice be “impossible he went on to describe a counterexample: to find.” Turing used his unbreakable machine example to defeat an argument against the possibility of artificial I have set up on the Manchester computer a small intelligence. -

The Turing Guide

The Turing Guide Edited by Jack Copeland, Jonathan Bowen, Mark Sprevak, and Robin Wilson • A complete guide to one of the greatest scientists of the 20th century • Covers aspects of Turing’s life and the wide range of his intellectual activities • Aimed at a wide readership • This carefully edited resource written by a star-studded list of contributors • Around 100 illustrations This carefully edited resource brings together contributions from some of the world’s leading experts on Alan Turing to create a comprehensive guide that will serve as a useful resource for researchers in the area as well as the increasingly interested general reader. “The Turing Guide is just as its title suggests, a remarkably broad-ranging compendium of Alan Turing’s lifetime contributions. Credible and comprehensive, it is a rewarding exploration of a man, who in his life was appropriately revered and unfairly reviled.” - Vint Cerf, American Internet pioneer JANUARY 2017 | 544 PAGES PAPERBACK | 978-0-19-874783-3 “The Turing Guide provides a superb collection of articles £19.99 | $29.95 written from numerous different perspectives, of the life, HARDBACK | 978-0-19-874782-6 times, profound ideas, and enormous heritage of Alan £75.00 | $115.00 Turing and those around him. We find, here, numerous accounts, both personal and historical, of this great and eccentric man, whose life was both tragic and triumphantly influential.” - Sir Roger Penrose, University of Oxford Ordering Details ONLINE www.oup.com/academic/mathematics BY TELEPHONE +44 (0) 1536 452640 POSTAGE & DELIVERY For more information about postage charges and delivery times visit www.oup.com/academic/help/shipping/. -

Edsger Dijkstra: the Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Edsger Dijkstra The Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders Krzysztof Apt s it turned out, the train I had taken from dsger dijkstra was born in Rotterdam in 1930. Nijmegen to Eindhoven arrived late. To make He described his father, at one time the president matters worse, I was then unable to find the right of the Dutch Chemical Society, as “an excellent Aoffice in the university building. When I eventually arrived Echemist,” and his mother as “a brilliant mathematician for my appointment, I was more than half an hour behind who had no job.”1 In 1948, Dijkstra achieved remarkable schedule. The professor completely ignored my profuse results when he completed secondary school at the famous apologies and proceeded to take a full hour for the meet- Erasmiaans Gymnasium in Rotterdam. His school diploma ing. It was the first time I met Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. shows that he earned the highest possible grade in no less At the time of our meeting in 1975, Dijkstra was 45 than six out of thirteen subjects. He then enrolled at the years old. The most prestigious award in computer sci- University of Leiden to study physics. ence, the ACM Turing Award, had been conferred on In September 1951, Dijkstra’s father suggested he attend him three years earlier. Almost twenty years his junior, I a three-week course on programming in Cambridge. It knew very little about the field—I had only learned what turned out to be an idea with far-reaching consequences. a flowchart was a couple of weeks earlier. -

The Turing Approach Vs. Lovelace Approach

Connecting the Humanities and the Sciences: Part 2. Two Schools of Thought: The Turing Approach vs. The Lovelace Approach* Walter Isaacson, The Jefferson Lecture, National Endowment for the Humanities, May 12, 2014 That brings us to another historical figure, not nearly as famous, but perhaps she should be: Ada Byron, the Countess of Lovelace, often credited with being, in the 1840s, the first computer programmer. The only legitimate child of the poet Lord Byron, Ada inherited her father’s romantic spirit, a trait that her mother tried to temper by having her tutored in math, as if it were an antidote to poetic imagination. When Ada, at age five, showed a preference for geography, Lady Byron ordered that the subject be replaced by additional arithmetic lessons, and her governess soon proudly reported, “she adds up sums of five or six rows of figures with accuracy.” Despite these efforts, Ada developed some of her father’s propensities. She had an affair as a young teenager with one of her tutors, and when they were caught and the tutor banished, Ada tried to run away from home to be with him. She was a romantic as well as a rationalist. The resulting combination produced in Ada a love for what she took to calling “poetical science,” which linked her rebellious imagination to an enchantment with numbers. For many people, including her father, the rarefied sensibilities of the Romantic Era clashed with the technological excitement of the Industrial Revolution. Lord Byron was a Luddite. Seriously. In his maiden and only speech to the House of Lords, he defended the followers of Nedd Ludd who were rampaging against mechanical weaving machines that were putting artisans out of work. -

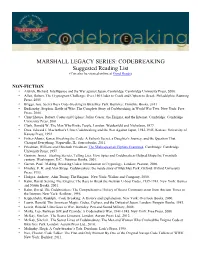

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and The

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and the Commodification of Reality, 1927-1945 By Joseph E.J. Clark B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 M.A., University of British Columbia, 2001 M.A., Brown University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2011 © Copyright 2010, by Joseph E.J. Clark This dissertation by Joseph E.J. Clark is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Susan Smulyan, Co-director Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Philip Rosen, Co-director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Lynne Joyrich, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Dean Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Joseph E.J. Clark Date of Birth: July 30, 1975 Place of Birth: Beverley, United Kingdom Education: Ph.D. American Civilization, Brown University, 2011 Master of Arts, American Civilization, Brown University, 2004 Master of Arts, History, University of British Columbia, 2001 Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1999 Teaching Experience: Sessional Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies, Simon Fraser University, Spring 2010 Sessional Instructor, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Fall 2008 Sessional Instructor, Department of Theatre, Film, and Creative Writing, University of British Columbia, Spring 2008 Teaching Fellow, Department of American Civilization, Brown University, 2006 Teaching Assistant, Brown University, 2003-2004 Publications: “Double Vision: World War II, Racial Uplift, and the All-American Newsreel’s Pedagogical Address,” in Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds. -

Campus Artworks

20 House of Phineas Gage 26 Lokey Science Complex Gargoyles “House of Phineas Gage” (2003), hidden in the courtyard Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Sir Isaac Newton, Maxwell & his of Straub Hall, is made of wooden strips. It was a 1% for Demon, Thomas Condon, Alan Turing, and John von Neumann CCampusampus ArtworksArtworks Art commission associated with the Lewis Center for are portrayed on the façades of the Lokey Science Complex Neuroimaging. The work was created by artist/architect buildings, along with sculptures of Drosophilia (fruit fl y) James Harrison. The “subject,” Phineas Gage, is a legend in and Zebrafi sh. The hammered sheet copper sculptures were the history of brain injury: he survived a 3-foot rod blown into designed and installed by artist Wayne Chabre between 1989- his head from a construction blast in 1848. 90. 21 “Aggregation” This art installation was a 1% for Art commision made by 27 Science Walk Adam Kuby as part of his series “disintegrated” art, in “Science Walk” is a landscape work that connects the major which he takes an object and breaks it down into several science buildings from Cascade Hall to Deschutes Hall. It smaller pieces. “Aggregation” is represented through six consists of inlaid stone and tile beginning at the fountain sites surrounding the EMU green, each containing a four- “Cascade Charley.” It was designed in 1991 by Scott Wylie. by-four granite block that was quarried in Eastern Oregon. The inlaid stones were donated by three members of the UO As one moves around the circle, the blocks break down into Geological Sciences faculty Allan Kays, Jack Rice and David smaller pieces from one solid cube to a cluster of 32 broken Blackwell. -

Alan M. Turing – Simplification in Intelligent Computing Theory and Algorithms”

“Alan Turing Centenary Year - India Celebrations” 3-Day Faculty Development Program on “Alan M. Turing – Simplification in Intelligent Computing Theory and Algorithms” Organized by Foundation for Advancement of Education and Research In association with Computer Society of India - Division II [Software] NASSCOM, IFIP TC - 1 & TC -2, ACM India Council Co-sponsored by P.E.S Institute of Technology Venue PES Institute of Technology, Hoskerehalli, Bangalore Date : 18 - 20 December 2012 Compiled by : Prof. K. Rajanikanth Trustee, FAER “Alan Turing Centenary Year - India Celebrations” 3-Day Faculty Development Program on “Alan M. Turing – Simplification in Intelligent Computing Theory and Algorithms” Organized by Foundation for Advancement of Education and Research In association with Computer Society of India - Division II [Software], NASSCOM, IFIP TC - 1 & TC -2, ACM India Council Co-sponsored by P.E.S Institute of Technology December 18 – 20, 2012 Compiled by : Prof. K. Rajanikanth Trustee, FAER Foundation for Advancement of Education and Research G5, Swiss Complex, 33, Race Course Road, Bangalore - 560001 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.faer.ac.in PREFACE Alan Mathison Turing was born on June 23rd 1912 in Paddington, London. Alan Turing was a brilliant original thinker. He made original and lasting contributions to several fields, from theoretical computer science to artificial intelligence, cryptography, biology, philosophy etc. He is generally considered as the father of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence. His brilliant career came to a tragic and untimely end in June 1954. In 1945 Turing was awarded the O.B.E. for his vital contribution to the war effort. In 1951 Turing was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. -

DVD Program Notes

DVD Program Notes Part One: Thor Magnusson, Alex Click Nilson is a Swedish avant McLean, Nick Collins, Curators garde codisician and code-jockey. He has explored the live coding of human performers since such Curators’ Note early self-modifiying algorithmic text pieces as An Instructional Game [Editor’s note: The curators attempted for One to Many Musicians (1975). to write their Note in a collaborative, He is now actively involved with improvisatory fashion reminiscent Testing the Oxymoronic Potency of of live coding, and have left the Language Articulation Programmes document open for further interaction (TOPLAP), after being in the right from readers. See the following URL: bar (in Hamburg) at the right time (2 https://docs.google.com/document/d/ AM, 15 February 2004). He previously 1ESzQyd9vdBuKgzdukFNhfAAnGEg curated for Leonardo Music Journal LPgLlCe Mw8zf1Uw/edit?hl=en GB and the Swedish Journal of Berlin Hot &authkey=CM7zg90L&pli=1.] Drink Outlets. Alex McLean is a researcher in the area of programming languages for Figure 1. Sam Aaron. the arts, writing his PhD within the 1. Overtone—Sam Aaron Intelligent Sound and Music Systems more effectively and efficiently. He group at Goldsmiths College, and also In this video Sam gives a fast-paced has successfully applied these ideas working within the OAK group, Uni- introduction to a number of key and techniques in both industry versity of Sheffield. He is one-third of live-programming techniques such and academia. Currently, Sam the live-coding ambient-gabba-skiffle as triggering instruments, scheduling leads Improcess, a collaborative band Slub, who have been making future events, and synthesizer design.