Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Fine Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Road Leads to Area “A” Under the Palestinian Authority, Beware of Entering: Palestinian Ghetto Policies in the West Bank

This Road Leads to Area “A” Under the Palestinian Authority, Beware of Entering: Palestinian Ghetto Policies in the West Bank Razi Nabulsi* “This road leads to Area “A” under the Palestinian Authority. The Entrance for Israeli Citizens is Forbidden, Dangerous to Your Lives, And Is Against The Israeli Law.” Anyone entering Ramallah through any of the Israeli military checkpoints that surround it, and surround its environs too, may note the abovementioned sentence written in white on a blatantly red sign, clearly written in three languages: Arabic, Hebrew, and English. The sign practically expires at Attara checkpoint, right after Bir Zeit city; you notice it as you leave but it only speaks to those entering the West Bank through the checkpoint. On the way from “Qalandia” checkpoint and until “Attara” checkpoint, the traveller goes through Qalandia Camp first; Kafr ‘Aqab second; Al-Amari Camp third; Ramallah and Al-Bireh fourth; Sarda fifth; and Birzeit sixth, all the way ending with “Attara” checkpoint, where the red sign is located. Practically, these are not Area “A” borders, but also not even the borders of the Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate, neither are they the West Bank borders. This area designated by the abovementioned sign does not fall under any of the agreed-upon definitions, neither legally nor politically, in Palestine. This area is an outsider to legal definitions; it is an outsider that contains everything. It contains areas, such as Kafr ‘Aqab and Qalandia Camp that belong to the Jerusalem municipality, which complies -

Talking Back in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Rational Dialogue Or Emotional Shouting Match?1

conflict & communication online, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2011 www.cco.regener-online.de ISSN 1618-0747 Elie Friedman Talking back in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: Rational dialogue or emotional shouting match?1 Kurzfassung: Das Internet erleichtert eine breite globale Konversation unter Bürgern und ermöglicht einen interkulturellen Dialog über eine Vielzahl von gesellschaftlich relevanten Fragen. Die vorliegende Arbeit untersucht die Beschaffenheit von „Talkback“-Diskursen auf Nachrichten-Web-Seiten im Rahmen des palästinensisch-israelischen Konflikts. Die Ergebnisse der Studie zeigen, dass viele der Antwort- schreiber sich einer kritisch-rationalen Diskussion über grundlegende Fragen des Konflikts verpflichten, jedoch oft auch rationale Argu- mente vorbringen, um entgegenstehende Meinungen zu delegitimieren. Der „Talkback“-Dialog ist durch eine engagierte Diskussion gekennzeichnet, wobei jedoch die Mehrheit der Antwortschreiber eher in Dialog mit dem jeweiligen Artikel treten als einen Dialog mit den anderen Antwortschreibern zu führen. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass der „Talkback“-Diskurs eine lebhafte, vielseitige und umfassende Form eines öffentlichen Raumes konstituiert, der den Austausch heterogener Meinungen ermöglicht, jedoch die Selbstdarstellung gegenüber der Auseinandersetzung mit den anderen bevorzugt. Abstract: The Internet has facilitated a broad global conversation among citizens, enabling cross-cultural dialogue on a range of issues, in particular through Web 2.0 tools. This study analyzes the nature of the talkback discourse on news web sites within the framework of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The study's findings demonstrated that several talkback writers engage in rational-critical discussion of is- sues essential to the conflict, although they often use rational arguments to de-legitimize conflicting opinions. Talkback dialogue is char- acterized by engaged discussion, though the majority of respondents engage in dialogue with the article, rather than with other talkback writers. -

Emily Jacir: Europa 30 Sep 2015 – 3 Jan 2016 Large Print Labels and Interpretation Galleries 1, 8 & 9

Emily Jacir: Europa 30 Sep 2015 – 3 Jan 2016 Large print labels and interpretation Galleries 1, 8 & 9 1 Gallery 1 Emily Jacir: Europa For nearly two decades Emily Jacir has built a captivating and complex artistic practice through installation, photography, sculpture, drawing and moving image. As poetic as it is political, her work investigates movement, exchange, transformation, resistance and silenced historical narratives. This exhibition focuses on Jacir’s work in Europe: Italy and the Mediterranean in particular. Jacir often unearths historic material through performative gestures and in-depth research. The projects in Europa also explore acts of translation, figuration and abstraction. (continues on next page) 2 At the heart of the exhibition is Material for a film (2004– ongoing), an installation centred around the story of Wael Zuaiter, a Palestinian intellectual who was assassinated outside his home in Rome by Israeli Mossad agents in 1972. Taking an unrealised proposal by Italian filmmakers Elio Petri and Ugo Pirro to create a fi lm about Zuaiter’s life as her starting point, the resulting installation contains documents, photographs, and sound elements, including Mahler’s 9th Symphony as one of the soundtracks to the work. linz diary (2003), is a performance by Jacir captured by one of the city’s live webcams that photographed the artist as she posed by a fountain in a public square in Linz, Austria, at 6pm everyday, over 26 days. During the performance Jacir would send the captured webcam photo of herself to her email list along with a small diary entry. In the series from Paris to Riyadh (drawings for my mother) (1998–2001), a collection of white vellum papers dotted with black ink are delicately placed side by side. -

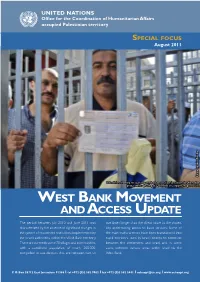

West Bank Movement Andaccess Update

UNITED NATIONS Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory SPECIAL FOCUS August 2011 Photo by John Torday John Photo by Palestinian showing his special permit to access East Jerusalem for Ramadan prayer, while queuing at Qalandiya checkpoint, August 2010. WEST BANK MOVEMENT AND ACCESS UPDATE The period between July 2010 and June 2011 was five times longer than the direct route to the closest characterized by the absence of significant changes in city, undermining access to basic services. Some of the system of movement restrictions implemented by the main traffic arteries have been transformed into the Israeli authorities within the West Bank territory. rapid ‘corridors’ used by Israeli citizens to commute There are currently some 70 villages and communities, between the settlements and Israel, and, in some with a combined population of nearly 200,000, cases, between various areas within Israel via the compelled to use detours that are between two to West Bank. P. O. Box 38712 East Jerusalem 91386 l tel +972 (0)2 582 9962 l fax +972 (0)2 582 5841 l [email protected] l www.ochaopt.org AUGUST 2011 1 UN OCHA oPt EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The period between July 2010 and June 2011 Jerusalem. Those who obtained an entry permit, was characterized by the absence of significant were limited to using four of the 16 checkpoints along changes in the system of movement restrictions the Barrier. Overcrowding, along with the multiple implemented by the Israeli authorities within the layers of checks and security procedures at these West Bank territory to address security concerns. -

Destination: Jerusalem Servees

Destination: Emily Jacir’s audio work Untitled (servees) was produced as a site specific work and Jerusalem Servees installed in 2008 at Damascus Gate, in Jerusalem’s Old City. It was displayed as Interview with part of the second edition of the Jerusalem Emily Jacir Show organized by The Ma’mal Foundation. In its form, content and location, it was a Adila Laidi-Hanieh crucible of contemporary Palestinian visual art and culture, of Jacir’s practice, and of Palestinian efforts to affirm presence and ownership of the city in the face of the forced ‘silent transfer’. Emily Jacir is one of the most successful Palestinian contemporary artists and one of the best known internationally, as well as arguably its most recognized. She won numerous prestigious awards including the 2008 Hugo Boss Prize of the Guggenheim Foundation in New York; where the Jury noted her, “rigorous conceptual practice… bears witness to a culture torn by war Photo courtesy Emily Jacir. and displacement through projects that © Emily Jacir 2009 unearth individual narratives and collective Jerusalem Quarterly 40 [ 59 ] experiences”. In 2007 she won the Prince Claus Award, an annual prize from the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development in the Hague, which described Jacir as, “an exceptionally talented artist whose works seriously engages the implications of conflict” (PCF). In 2007, she won the ‘Leone d’Oro a un artista under 40’ - (Golden Lion Award for an artist under 40), at the Venice Biennale, the oldest and premier international art event in Europe, often dubbed ‘the Olympics of art’, for “a practice that takes as its subject exile in general and the Palestinian issue in particular, without recourse to exoticism”. -

Remote Control: Distance in Two Works by Emily Jacir and Wafaa Bilal

Remote Control: Distance in Two Works by Emily Jacir and Wafaa Bilal Kerr Houston s a part of her 2001-3 project Where We Come honor of all those who gave their lives for Palestine.” To From, the Palestinian-American artist Emily Jacir the right, the beach appeared, in early morning blues, on Aasked dozens of Palestinian exiles and children a small video screen. of Palestinian refugees a simple question: “If I could do Four years later, in May and June of 2007, the anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it Iraqi-American artist Wafaa Bilal took up residence be?” Able to travel relatively freely within Israel due to in a Chicago art gallery, in a project called Domestic her American passport, Jacir then executed the wishes Tension. Subsisting on donated food and drink, Bilal of several respondents, recording her performances in lived for thirty days in a simulated bedroom/office space photographs and videos, which she exhibited alongside that was enclosed in transparent walls. Visible to gallery transcriptions of the requests and brief personal histories visitors, the space was also outfitted with computers of the exiles (Figure 1). “Drink the water,” ran one and a streaming webcam, and visitors to Bilal’s website appeal, put forward by a woman named Omayma, “in could control the camera and periodically interact with my parents’ village” – and, adjacent, viewers saw an him through an online chatroom or view videos that he image of a glassful of water, tilted towards the camera. posted on Youtube. Or they could attempt to shoot him, “Go to Haifa’s beach at the moment of the first light,” read another request, made by a man named Mohannad, Figure 1. -

Art As a Powerful Tool for Knowledge

NESRINE REZEK Art as a Powerful Tool for Knowledge Most of us believe in the power of art, how story can change one’s life, with stories we can connect with other, we reach others who we may never meet, words gathering to form sentences, to fabric stories, to form our history our culture our identity and our future, simply our life is a story. It’s our way to share our experience with others, the ability to express our interests, to discuss our goals, and to reach positive change. From here Emily Jacir began her fight and journey to tell her story or our story, to uncover facts and to convey the truth to the world. Emily Jacir “is Palestinian artist and filmmaker. Born in Bethlehem in 1970, Jacir attended the University of Dallas, Irving, the Memphis College of Art and the Whitney Independent Study Program and has been living and working between New York and the West Bank. It may be argued one of the main Palestinian artists working today, she has received a number of prominent awards. Jacir utilizes different kinds of media such as video, film, installation, sound, photography, performance, and writing in her work and has shown widely throughout Europe, United States and the Middle East since 1994.”1 Her style was different, through her artistic work, Jacir gives the narrative right to the Palestinian, and re-focuses on the details of the Palestinian life before Nakba. She shows how pictures as one form of narrativity through narratological concepts is a powerful tool to reproduce meanings, in order to represent and retrieve history. -

DISPLACED in THEIR OWN CITY the Impact of Israeli Policy in East Jerusalem on the Palestinian Neighborhoods of the City Beyond the Separation Barrier June 2015

DISPLACED IN THEIR OWN CITY THE IMPACT OF ISRAELI POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ON THE PALESTINIAN NEIGHBORHOODS OF THE CITY BEYOND THE SEPARATION BARRIER JUNE 2015 27 King George St., P.O. Box 2239, Jerusalem 94581 Telephone: 972-2-6222858 | Fax: 972-2-6233696 www.ir-amim.org.il | [email protected] DISPLACED IN THEIR OWN CITY THE IMPACT OF ISRAELI POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ON THE PALESTINIAN NEIGHBORHOODS OF THE CITY BEYOND THE SEPARATION BARRIER JUNE 2015 Written by: Ehud Tagari and Yudith Oppenheimer Research: Eyal Hareuveni and Aviv Tatarsky Hebrew editing: Lea Klibanoff Ron English translation: Shaul Vardi English editing: Betty Herschman Photography: Ahmad Sub Laban Thanks to: Atty. Oshrat Maimon, Atty. Nisreen Alyan of the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI), Christoph von Toggenburg of the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), Roni Ben Efrat and Erez Wagner of WAC-MAAN, the Workers Advice Center, Lior Volinz of Amsterdam University, Atty. Elias Khoury, and Eetta Prince-Gibson. This publication was produced by Ir Amim (“City of Nations”) in the framework of a joint project with the Workers Advice Center WAC-MAAN aimed at strengthening the socio-economic rights of East Jerusalem residents. We thank the European Union, the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Israel, and The Moriah Fund for their support. The content of this publication is the responsibility of Ir Amim alone. taBLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter One: Israeli Policy in East Jerusalem since 1967 8 A. Annexation and Confiscation . 8 B. Ensuring a Jewish Majority . 9 C. Non-Registration of Land. 10 D. -

The Reality of Palestinian Refugee Camps in Light of COVID-19”

A Policy Paper entitled: “The Reality of Palestinian Refugee Camps in light of COVID-19” Written by: Raed Mohammad Al-Dib’i Introduction: According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, there are 58 official Palestinian refugee camps affiliated to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), of which 10 are in Jordan, 9 in Syria, 12 in Lebanon, 19 in the West Bank and 8 in the Gaza Strip. However, there are a number of camps that are not recognized by the UNRWA.1 17% of the 6.2 million Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA reside in the West Bank, compared to 25% in the Gaza Strip; while the rest is distributed among the diaspora, including the Arab countries.2 The Coronavirus pandemic poses a great challenge in addition to those that the Palestinian refugees already encounter in refugee camps, compared to other areas for a number of reasons, including the low level of health services provided by UNRWA - originally modest - especially after the latter's decision to reduce its services to refugees, the high population density in the camps, which makes the implementation of public safety measures, social distancing and home quarantine to those who have COVID-19 and who they were in contact with a complex issue. Another reason is the high rate of unemployment in the Palestinian camps, which amounts to 39%, compared to 22% for non-refugees3, thus, constituting an additional challenge in light of the pandemic. The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) adopts the policy of partial or complete closure to combat the COVID-19 outbreak in light of the inability to provide the requirements for a decent life to all of its citizens for numerous reasons. -

Ex-Communicated:限 Historicalreflectionsonenclosure

Photo Essays Ex-Communicated: HistoricalReflectionsonEnclosure LandscapesinPalestine Gary Fields From a small hilltop on the Beit Hanina side of the Qalandia checkpoint near the Palestinian town of Ramallah, a landscape of imposing built forms and regi- mented human bodies beckons to a theme now central to historical studies, the nature of modern power and its relationship to territorial space. To the north of the checkpoint, a concrete wall emerges from the western horizon and sweeps forcefully across the land, partially concealing the town of Qalandia behind its grayish, fore- boding exterior (fig. 1). Along the once vibrant Jerusalem- Ramallah road where the Palestinian towns of Ar Ram, Beit Hanina, and Qalandia formerly converged, a sec- ond wall runs perpendicular to and eventually connects with the first, disconnecting these towns from one another while emitting an unmistakable aura of emptiness and immobility. In the space where these towns were once joined together stand several prison- like guard towers that now surround the checkpoint terminal. Here, under the gaze of mostly young military overseers, Palestinians are processed as they try to move from one geographical location to another. While this landscape is dramatic in the way it reconfigures land and controls the movements of people, it is not unique. Many other venues distributed throughout the West Bank host the same drama of power and space in which military authorities and Palestinian civilians engage in similarly scripted rituals of domination and submission, with the same stage set of coldly formidable architectural forms invariably hovering over the actors below. Radical History Review Issue 108 (Fall 2010) d o i 10.1215/01636545-2010-008 © 2010 by MARHO: The Radical Historians’ Organization, Inc. -

Qalandia Checkpoint – Renamed RAF Lydda in 1943, and Ben in 2005, from the Jerusalem/Israel Side

Qalandia Introduction: A Gate to the World Checkpoint: Qalandia. The name evokes a village, a The Historical refugee camp, a women’s handicraft co- operative (run through the refugee camp), Geography of a a used-to-be airport. And now a formidable Non-Place checkpoint. In the old days, Qalandia was a small village off the main Ramallah- Helga Tawil-Souri Jerusalem road, today home to about a thousand people. In 1949, Qalandia became synonymous with a UNRWA refugee camp, whose population today is over eleven- thousand people, and within which is the first refugee women’s society. But Qalandia also used to be an airport. For a few short years in the 1930s this was the only airport in British Mandate Palestine used by the British military (before the Wilhelma Airport A bird’s eye view of the Qalandia checkpoint – renamed RAF Lydda in 1943, and Ben in 2005, from the Jerusalem/Israel side. In the distance one can see the wall/separation Gurion Airport in 1973 – opened in Lydda, barrier being erected; the terminal that southeast of Tel Aviv); it was also the only appears by 2006 is under construction on the airport in Jordanian controlled territories right; the hilltop that used to exist in the right forefront is gone and a new control tower sits (i.e the West Bank and Jordan) post-1948 in its place. Photo taken by the author. until Amman boasted its own. After the [ 26 ] Sakakini Defrocked Jordanians took it over, they turned it into a civil airport and renamed it Jerusalem Airport in the 1950s, where it remained under Jordanian control until 1967, after which it was unilaterally incorporated in the Greater Jerusalem Municipal Area annexed by Israel. -

Grades One Through Six Had an Enjoyable Trip to the North of the Country, and It Was Educational As Well. They

Trip 1-6- All grades one through six had an enjoyable trip to the north of the country, and it was educational as well. They learned about the olive press and the old tools and methods of farming and irrigation. They also experienced the traditional transportation means of the carte and mule Art Exhibition At Al Hoash Art Gallery grades 4, 5 and 6 lived the memoirs of the Palestinian artist Mustafa Hallaj. Hallaj who had lost his homeland like most of the Palestinians in 1948, lived after the Nakba between Syria and Lebanon. His art work, done through carving on wood and then printed on paper and cloth depicted his love and longing to his homeland. After having an enjoyable time at the exhibition and listening to the life story of the artist, the gallery asked the children to fill out a questionnaire to assess how much they actually benefited from the visit. Fundraising dinner – To help meet the financial crisis, a Fundraising Dinner was held at the Terra Sancta Centre in Beit Hanina, a suburb north of Jerusalem on the 8th of November 2012. The response of the local community was beautiful and very encouraging to start planning for another one next year. The General assembly and board of Rawdat El-Zuhur worked with a lovely spirit as a team to make the evening enjoyable and successful. Mrs Rania Elias Khoury, the MC for the evening, led the guests through the historical journey of Rawdat El-Zuhur by means of photos and caption, followed by a quiz show.