Directions; Miles Davis. Jazz in Transition, 1968-1971

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Directory P&E 2021X Copy with ADS.Indd

Annual Directory of Producers & Engineers Looking for the right producer or engineer? Here is Music Connection’s 2020 exclusive, national list of professionals to help connect you to record producers, sound engineers, mixers and vocal production specialists. All information supplied by the listees. AGENCIES Notable Projects: Alejandro Sanz, Greg Fidelman Notable Projects: HBO seriesTrue Amaury Guitierrez (producer, engineer, mixer) Dectective, Plays Well With Others, A440 STUDIOS Notable Projects: Metallica, Johnny (duets with John Paul White, Shovels Minneapolis, MN JOE D’AMBROSIO Cash, Kid Rock, Reamonn, Gossip, and Rope, Dylan LeBlanc) 855-851-2440 MANAGEMENT, INC. Slayer, Marilyn Manson Contact: Steve Kahn Studio Manager 875 Mamaroneck Ave., Ste. 403 Tucker Martine Email: [email protected] Mamaroneck, NY 10543 Web: a440studios.com Ryan Freeland (producer, engineer, mixer) facebook.com/A440Studios 914-777-7677 (mixer, engineer) Notable Projects: Neko Case, First Aid Studio: Full Audio Recording with Email: [email protected] Notable Projects: Bonnie Raitt, Ray Kit, She & Him, The Decemberists, ProTools, API Neve. Full Equipment list Web: jdmanagement.com LaMontagne, Hugh Laurie, Aimee Modest Mouse, Sufjan Stevens, on website. Mann, Joe Henry, Grant-Lee Phillips, Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros, Promotional Videos (EPK) and concept Isaiah Aboln Ingrid Michaelson, Loudon Wainwright Mavis Staples for bands with up to 8 cameras and a Jay Dufour III, Rodney Crowell, Alana Davis, switcher. Live Webcasts for YouTube, Darryl Estrine Morrissey, Jonathan Brooke Thom Monahan Facebook, Vimeo, etc. Frank Filipetti (producer, engineer, mixer) Larry Gold Noah Georgeson Notable Projects: Vetiver, Devendra AAM Nic Hard (composer, producer, mixer) Banhart, Mary Epworth, EDJ Advanced Alternative Media Phiil Joly Notable Projects: the Strokes, the 270 Lafayette St., Ste. -

A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988)

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation Reynolds, Lyndon. 1975. ‘Miles et Alia’. Contact, 11. pp. 23-26. ISSN 0308-5066. ! [I] LYNDON REYNOLDS Ill Miles et Alia The list of musicians who have played with Miles Davis since 1966 contains a remarkable number of big names, including Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, Chick Corea, Joe Zawinul, Jack de Johnette, Dave Hol l and, John McLaughlin and Miroslav Vitous. All of these have worked success fully without Miles, and most have made a name for themselves whilst or since working with him. Who can say whether this is due to the limelight given them by playing alongside , Miles, the musical rewards of working with him, or Miles's talent-spotting abili- ties? Presumably the truth is a mixture of all these. What does Miles's music owe to the creative personalities of the musicians working with him? This question is unanswerable in practice, for one cannot quan- tify individual responsibility for a group product - assuming that is what Miles's music is. It is obvious that he has chosen very creative musicians with which to work, and yet there has often been an absence of conspicuous, individual, free solo playing in his music since about 1967. It would appear that Miles can absorb musical influences without losing his balance. What we find then, is a nexus of interacting musicians, centring on Miles; that is, musicians who not only play together in various other combinations, but influence each other as well. Even if the web could be disentangled (I know not how, save with a God's-eye-view), a systematic review of all the music that lies within it would be a task both vast and boring. -

Album Covers Through Jazz

SantiagoAlbum LaRochelle Covers Through Jazz Album covers are an essential part to music as nowadays almost any project or single alike will be accompanied by album artwork or some form of artistic direction. This is the reality we live with in today’s digital age but in the age of vinyl this artwork held even more power as the consumer would not only own a physical copy of the music but a 12’’ x 12’’ print of the artwork as well. In the 40’s vinyl was sold in brown paper sleeves with the artists’ name printed in black type. The implementation of artwork on these vinyl encasings coincided with years of progress to be made in the genre as a whole, creating a marriage between the two mediums that is visible in the fact that many of the most acclaimed jazz albums are considered to have the greatest album covers visually as well. One is not responsible for the other but rather, they each amplify and highlight each other, both aspects playing a role in the artistic, musical, and historical success of the album. From Capitol Records’ first artistic director, Alex Steinweiss, and his predecessor S. Neil Fujita, to all artists to be recruited by Blue Note Records’ founder, Alfred Lion, these artists laid the groundwork for the role art plays in music today. Time Out Sadamitsu "S. Neil" Fujita Recorded June 1959 Columbia Records Born in Hawaii to japanese immigrants, Fujita began studying art Dave Brubeck- piano Paul Desmond- alto sax at an early age through his boarding school. -

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site

M ARTIN VAN BUREN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY, 1974-2006 SUZANNE JULIN NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NORTHEAST REGION HISTORY PROGRAM JULY 2011 i Cover Illustration: Exterior Restoration of Lindenwald, c. 1980. Source: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 Chapter One: Recognizing Lindenwald: The Establishment Of Martin Van Buren National Historic Site 5 Chapter Two: Toward 1982: The Race To The Van Buren Bicentennial 27 Chapter Three: Saving Lindenwald: Restoration, Preservation, Collections, and Planning, 1982-1987 55 Chapter Four: Finding Space: Facilities And Boundaries, 1982-1991 73 Chapter Five: Interpreting Martin Van Buren And Lindenwald, 1980-2000 93 Chapter Six: Finding Compromises: New Facilities And The Protection of Lindenwald, 1992-2006 111 Chapter Seven: New Possibilities: Planning, Interpretation and Boundary Expansion 2000-2006 127 Conclusion: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Administrative History 143 Appendixes: Appendix A: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Visitation, 1977-2005 145 Appendix B: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Staffi ng 147 Appendix C: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Studies, Reports, And Planning Documents 1936-2006 151 Bibliography 153 Index 159 v LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1.1. Location of MAVA on Route 9H in Kinderhook, NY Figure 1.2. Portrait of the young Martin Van Buren by Henry Inman, circa 1840 Library of Congress Figure 1.3. Photograph of the elderly Martin Van Buren, between 1840 and 1862 Library of Congress Figure 1.4. James Leath and John Watson of the Columbia County Historical Society Photograph MAVA Collection Figure 2.1. -

Stan Magazynu Caĺ†Oĺıäƒ Lp Cd Sacd Akcesoria.Xls

CENA WYKONAWCA/TYTUŁ BRUTTO NOŚNIK DOSTAWCA ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST 159,99 SACD BERTUS ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST (NUMBERED 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - BROTHERS AND SISTERS (NUMBE 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - EAT A PEACH (NUMBERED LIMIT 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - IDLEWILD SOUTH (GOLD CD) 129,99 CD GOLD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ASIA - ASIA 179,99 SACD BERTUS BAND - STAGE FRIGHT (HYBRID SACD) 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - MUSIC FROM BIG PINK (NUMBERED LIMITED 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - THE LAST WALTZ (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITI 179,99 2 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BASIE, COUNT - LIVE AT THE SANDS: BEFORE FRANK (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BIBB, ERIC - BLUES, BALLADS & WORK SONGS 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - JUST LIKE LOVE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - RAINBOW PEOPLE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - GOOD STUFF 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - SPIRIT & THE BLUES 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BLIND FAITH - BLIND FAITH 159,99 SACD BERTUS BOTTLENECK, JOHN - ALL AROUND MAN 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 CAMEL - RAIN DANCES 139,99 SHMCD BERTUS CAMEL - SNOW GOOSE 99,99 SHMCD BERTUS CARAVAN - IN THE LAND OF GREY AND PINK 159,99 SACD BERTUS CARS - HEARTBEAT CITY (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITION HY 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS AFTER HOURS (NUMBERED LI 99,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS OF RAY CHARLES (NUMBERED 129,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY -

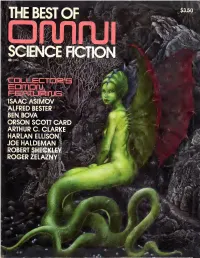

Best of OMNI Issue #1

i * HI 111 1 seiHCEraafioN EDITOQA ^ FEl^TJJliirUE: ISAAC asjjmov ALFRED BESTER BEN BOVA ORSON SCOTT CARD ARTHUR C. CLARKE ( HARLAN ELLISONf JOE HALDEMAN 1 ROBERT SHE©KU^ ROGER ZELAZNY& THE BEST OF onnrui SCIENCE FCTION EDITED BY BEN BOVA AND DON MYRUS DO OMNI SOCIETY THE BEST OF onnrui SCIENCE FICTION FOL.NDI few by Iscac Asir-ic-.: i i,s"al;cn by H R, Giger IAT TELLS THE TIME fit y HclanFI ison. lustro~-cn by 'vlaf. -(lorwein - : c ci cl! Lee-;, fex" ba Kara een vein Cera. Ls-'OicnoyEveyri byb' by Scot Morns siralionoy ivelya oyer okoloy tsx' by F C. Duront III I m NO FUTURE IN IT fiction by Joe Haldeirar . aire ;.- by C ofrti ed -e -weir, - GALATEA GALANTE fiction c-v '''ea Bey ei ; lustration by H. R. Giger ALIEN LANDSCAPES pictorial by Les Edwards, John Harris, Terry Ookes, and Tony Roberts y^\ KINS VAN fict on by Ben Rove, i ustronor by John Schoenherr SPACE CITIES pictorial by Harry Harrison Cover pointing by Pierre Lacombe HALFJACKficorioy ~'cy? '.<? -:-. .:.-'- v -:.- bv Ivtchsl Henricot SANDKINGS fiction by George R. R Martin llustrafol by Ernst Fuchs PLANET STORV pictor c ey - rr 3'ir^s a:-'d -crry Harrison : ARTHUR C.C .ARk'E!,-i:ef,igvv a-d i ...s-ofc', ::v VcIcoItsS. Kirk Copyriari jM9.'5. '97y. !930 by Or.n. P..Ld--:lioni- -te-e.:!cnal -id All nglrs 'ess : aiaies o ArTon,.;. Ni :!.-: c""""b so;* tray ::,; epr-duosd n; -'onsTii-tec n any torn- o- 'lecfifl-ica i--:udinc bhr-.iDr.c-pvi-g (eco'OV'g. -

The Sock Hop and the Loft: Jazz, Motown, and the Transformation of American Culture, 1959-1975

The Sock Hop and the Loft: Jazz, Motown, and the Transformation of American Culture, 1959-1975 The Commerce Group: Kat Breitbach, Laura Butterfield, Ashleigh Lalley, Charles Rosentel Steve Schwartz, Kelsey Snyder, Al Stith In the words of the prolific Peter Griffin, “It doesn’t matter if you’re black or white. The only color that really matters is green.” Notwithstanding the music industry’s rampant racism, the clearest view of how African Americans transformed popular music between 1959 and 1975 is through the lens of commerce. Scrutinizing the relationship between creators and consumers opens up a broad view of both visual and auditory arts. The sources we selected range from cover art and an Andy Warhol silkscreen to books on the industry’s backroom deals and the Billboard Hot 100 to a retrospective Boyz II Men album on Motown’s history and an NPR special on Jimi Hendrix for kids. Combining both sight and sound, we offer online videos, a documentary on jazz, and blaxploitation films. The unparalleled abilities of Motown’s music to transcend racial barriers and serve as a catalyst for social change through an ever-widening audience necessitates a study of Berry Gordy’s market sense and the legacy of his “family” in popular culture from the 1970s through today. First, the ubiquity of the Motown sound meant that a young, interracial audience enjoyed music that had been largely exclusive to black communities. The power of this “Sound of Young America” crossover was punctuated by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s affirmation in his “Transforming a Neighborhood into a Brotherhood” address that radio’s capacity to bridge black and white youth through music and create “the language of soul” surpasses even Alexander the Great’s conquests. -

Miles Davis (1926-1991)

Roots of American Music Biography: Miles Davis (1926-1991) Miles Davis is the most revered jazz trumpeter of all time, not to mention one of the most important musicians of the 20th century. He was the first jazz musician of the post-hippie era to incorporate rock rhythms, and his immeasurable influence on others, in both jazz and rock, encouraged a wealth of subsequent experiments. From the bebop licks he initially played with saxophonist Charlie Parker to the wah-wah screeds he concocted to keep up with Jimi Hendrix, Davis was as restless as a performer could get. Davis was raised in an upper-middle-class home in an integrated East St. Louis neighborhood. His father was a dentist; his mother, a music teacher. In 1941 he began playing the trumpet semiprofessionally with St. Louis jazz bands. The skills were there. Four years later, his father sent him to study at New York's Juilliard School of Music. Immediately upon arriving in New York City, Davis sought out alto saxophonist Parker, whom he had met the year before in St. Louis. He became Parker's roommate and protégé, playing in his quintet on the 1945 Savoy sessions, the definitive recordings of the bebop movement. He dropped out of Juilliard and played with Benny Carter, Billy Eckstine, Charles Mingus, and Oscar Pettiford. As a trumpeter Davis was far from virtuosic, but he made up for his technical limitations by emphasizing his strengths: his ear for ensemble sound, unique phrasing, and a distinctively fragile tone. He started moving away from speedy bop and toward something more introspective. -

Silent Way: Listening Past Black Visuality in Symbiopsychotaxiplasm

Close-Up: Black Film and Black Visual Culture In a (Not So) Silent Way: Listening Past Black Visuality in Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Charles “Chip” P. Linscott Abstract T is article considers William Greaves’s singular cinematic experiment Symbio- psychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) in light of the common expectation that black- ness is a readily available visual fact. A seemingly oblique engagement with blackness is foundational to the f lm’s overarching strategies of misdirection and promotes par- ticular resonances between race and sound. Following, I explore the problematic nature of black visuality and critique the notion that Symbio lacks any perspicuous engage- ment with race. Since the visual is clearly the dominant mode of engagement with black- ness, Symbio elides this black visuality by f guring blackness dif erently; it sounds, sings, and performs blackness instead of visualizing it. Music (Miles Davis’s In a Silent Way), sound (primarily noise), and performance (particularly an oppositional vernacular performativity in line with what W. T. Lhamon calls “optic black”) rise to the fore. Ultimately, the engagement with sonic relations opens race to audiovisual practices of improvisation, jazz, noise, and remixing. Blackness thus emerges as performative, dis- ruptive, relational, noisy, improvised, and available for reappropriation and remixing. Is silence simply a matter of not playing? —JOHN MOWITT, SOUNDS: THE AMBIENT HUMANITIES 1 I always listen to what I can leave out. —MILES DAVIS But now . let me hear your . let me hear the sound. —WILLIAM GREAVES, SYMBIOPSYCHOTAXIPLASM Charles P. “Chip” Linscott, “Close-Up: Black Film and Black Visual Culture: In a (Not So) Silent Way: Listening Past Black Visuality in Symbiopsychotaxiplasm.” Black Camera: An International Film Journal 8, no. -

Miles Davis Water Babies Mp3, Flac, Wma

Miles Davis Water Babies mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Water Babies Country: Netherlands Released: 1986 Style: Post Bop, Fusion MP3 version RAR size: 1638 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1889 mb WMA version RAR size: 1523 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 463 Other Formats: MPC AIFF MMF WAV DTS APE XM Tracklist Hide Credits Water Babies A1 5:06 Composed By – W. Shorter* Capricorn A2 8:27 Composed By – W. Shorter* Sweet Pea A3 7:59 Composed By – W. Shorter* Two Faced B1 18:01 Bass – Dave HollandComposed By – W. Shorter*Keyboards – Chick Corea Dual Mr. Tillman Anthony B2 13:18 Bass – Dave HollandComposed By – W. ProcessKeyboards – Chick Corea Companies, etc. Recorded At – Columbia Recording Studios Credits Bass – Ron Carter Drums – Tony Williams* Engineer [Recording] – Stan Tonkel Engineer [Remix] – Russ Payne, Stan Weiss Illustration – Corky McCoy Keyboards – Herbie Hancock Producer – Teo Macero Soprano Saxophone, Tenor Saxophone – Wayne Shorter Trumpet – Miles Davis Notes Recorded at Columbia Recording Studios, New York. Rec. Date: A1, A2 June 1967, B1, B2 November 1968, A3 July 1969. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Miles Water Babies (LP, PC 34396 Columbia PC 34396 US 1976 Davis Album) Water Babies (CD, Miles ООО JPCD9804220 Album, RE, JPCD9804220 Russia Unknown Davis "ДОРА" Unofficial) Miles Water Babies (LP, 81741 CBS 81741 Portugal Unknown Davis Album, RE) Miles Water Babies (LP, CBS 21136 CBS CBS 21136 Netherlands 1986 Davis Album, RE) Miles Water Babies (LP, 23AP 2572 CBS/Sony