Accepted Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dick Higgins Papers, 1960-1994 (Bulk 1972-1993)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1d5n981n No online items Finding aid for the Dick Higgins papers, 1960-1994 (bulk 1972-1993) Finding aid prepared by Lynda Bunting. Finding aid for the Dick Higgins 870613 1 papers, 1960-1994 (bulk 1972-1993) ... Descriptive Summary Title: Dick Higgins papers Date (inclusive): 1960-1994 (bulk 1972-1993) Number: 870613 Creator/Collector: Higgins, Dick, 1938-1998 Physical Description: 108.0 linear feet(81 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: American artist, poet, writer, publisher, composer, and educator. The archive contains papers collected or generated by Higgins, documenting his involvement with Fluxus and happenings, pattern and concrete poetry, new music, and small press publishing from 1972 to 1994, with some letters dated as early as 1960. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Dick Higgins is known for his extensive literary, artistic and theoretical activities. Along with his writings in poetry, theory and scholarship, Higgins published the well-known Something Else Press and was a cooperative member of Unpublished/Printed Editions; co-founded Fluxus and Happenings; wrote performance and graphic notations for theatre, music, and non-plays; and produced and created paintings, sculpture, films and the large graphics series 7.7.73. Higgins received numerous grants and prizes in support of his many endeavors. Born Richard Carter Higgins in Cambridge, England, March 15, 1938, Higgins studied at Columbia University, New York (where he received a bachelors degree in English, 1960), the Manhattan School of Printing, New York, and the New School of Social Research, 1958-59, with John Cage and Henry Cowell. -

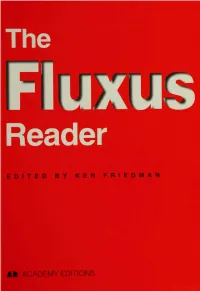

PDF (Fluxus Reader 3A Chapter 6 Saper)

EDITED BY KEN E D M A N #.». ACADEMY EDIT I THE FLUXUS READER Edited by KEN FRIEDMAN AI ACADEMY EDITIONS First published in Great Britain in 1998 by ACADEMY EDITIONS a division of John Wiley & Sons, Baffins Lane, Chichester, West Sussex P019 1UD Copyright © 1998 Ken Friedman. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright. Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, UK, W1P 9HE, without the permission in writing of the publisher and the copyright holders. Other Wiley Editorial Offices New York • Weinheim • Brisbane • Singapore • Toronto ISBN 0-471-97858-2 Typeset by BookEns Ltd, Royston, Herts. Printed and bound in the UK by Bookcraft (Bath) Ltd, Midsomer Norton Cover design by Hybert Design CONTENTS Acknowledgemen ts iv Ken Friedman, Introduction: A Transformative Vision of Fluxus viii Part I THREE HISTORIES O)ven Smith, Developing a Fluxable Forum: Early Performance and Publishing 3 Simon Anderson, Pluxus, Fluxion, Flushoe: The 1970s 22 Hannah Higgins, Fluxus Fortuna 31 Part II THEORIES OF FLUXUS Ina Blom. Boredom and Oblivion 63 David T Doris, Zen Vaudeville: A Medi(t)ation in the Margins of Pluxus 91 Craig Saper, Fluxus as a Laboratory 136 Part III CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES Estera Milman, Fluxus History and Trans-History: Competing -

The Fluxus Performance Workbook, Opus 25 15 Published in 1990

the FluxusP erformanceW orkbook edited by Ken Friedman, Owen Smith and Lauren Sawchyn a P erformance Research e-publication 2002 the FluxusP erformanceWorkbook introduction to the fortieth anniversary edition The first examples of what were to become Fluxus event scores date back to John Cage's famous class at The New School, where artists such as George Brecht, Al Hansen, Allan Kaprow, and Alison Knowles began to create art works and performances in musical form. One of these forms was the event. Events tend to be scored in brief verbal notations. These notes are known as event scores. In a general sense, they are proposals, propositions, and instructions. Thus, they are sometimes known as proposal pieces, propositions, or instructions. Publications, 2002 - The first collections of Fluxus event scores were the working sheets for Fluxconcerts. They were generally used only by the artist-performers who were presenting the work. With the birth of Fluxus publishing, however, collections of event scores soon came to take three forms. The first form was the boxed collection. These were individual scores written or printed on cards. The , Performance Research e classic example of this boxed collection is George Brecht's Water Yam. A second format was the book or Sawchyn pamphlet collection of scores, often representing work by a single artist. Yoko Ono's Grapefruit is probably the best known of these collections. Now forgotten, but even more influential during the 1960s, were the small collections that Dick Higgins published in the Something Else Press pamphlet series under the Great Bear imprint. These small chapbooks contained work by Bengt af Klintberg, Alison Knowles, Nam June Paik, and many other artists working in the then-young Fluxus and intermedia traditions. -

Fluxus Performance Workbook, Opus 25 15 Published in 1990

the FluxusP erformanceW orkbook edited by Ken Friedman, Owen Smith and Lauren Sawchyn a P erformance Research e-publication 2002 the FluxusP erformanceWorkbook introduction to the fortieth anniversary edition The first examples of what were to become Fluxus event scores date back to John Cage's famous class at The New School, where artists such as George Brecht, Al Hansen, Allan Kaprow, and Alison Knowles began to create art works and performances in musical form. One of these forms was the event. Events tend to be scored in brief verbal notations. These notes are known as event scores. In a general sense, they are proposals, propositions, and instructions. Thus, they are sometimes known as proposal pieces, propositions, or instructions. Publications, 2002 - The first collections of Fluxus event scores were the working sheets for Fluxconcerts. They were generally used only by the artist-performers who were presenting the work. With the birth of Fluxus publishing, however, collections of event scores soon came to take three forms. The first form was the boxed collection. These were individual scores written or printed on cards. The , Performance Research e classic example of this boxed collection is George Brecht's Water Yam. A second format was the book or Sawchyn pamphlet collection of scores, often representing work by a single artist. Yoko Ono's Grapefruit is probably the best known of these collections. Now forgotten, but even more influential during the 1960s, were the small collections that Dick Higgins published in the Something Else Press pamphlet series under the Great Bear imprint. These small chapbooks contained work by Bengt af Klintberg, Alison Knowles, Nam June Paik, and many other artists working in the then-young Fluxus and intermedia traditions. -

Fluxus Games and Contemporary Folklore: on the Non-Individual Character of Fluxus Art

Bengt af Klintberg Fluxus Games and Contemporary Folklore: on the Non-Individual Character of Fluxus Art (Paper read at the symposium In the Spirit of Fluxus at Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, February 12-13, 1993) j(?1/i I Offprint from Konsthistorisk Tidskrift Vol. LXll:2, 1993 Fluxus Games and Contemporary Folklore: on the Non-Individual Character of Fluxus Art BENGT AF KLINTBERG The similarities and differences between the most distinctive and important achievement. work of individual Fluxus artists have been They are characterized by such a striking simi much debated. The views expressed are diver larity that it is legitimate to talk about an art gent, to say the least. The artists themselves form with a conscious non-individual character. stress their indi vi dualism. Eric Andersen, for It is, as a matter of fact, difficult for a person example, has claimed that the only uniting factor who sees photo documentation of these early is that the Fluxus artists happened to appear pieces or reads or hears descriptions of them te together in public at a certain time. At a press decide which one of the artists is the originator. conferencc held in Copenhagen in connection Ken Friedman has recently collected a great with the arrangement "ExceUent 1992" several deal of them in The Fluxus Performance Work of the artists present protested against being book (Friedman 1990b ). Something that strikes calJcd a group. the reader is that this volume from 1990 is ac There are, nevertheless, Fluxus artists as well tually the first attempt at collecting scores of as art critics who see many uniting factors in the performance pieces by all artists who have been works which have been presented as Fluxus art. -

Fluxusp Erformancew Orkbook Edited by Ken Friedman, Owen Smith and Lauren Sawchyn

the FluxusP erformanceW orkbook edited by Ken Friedman, Owen Smith and Lauren Sawchyn a P erformance Research e-publication 2002 the FluxusP erformanceWorkbook introduction to the fortieth anniversary edition The first examples of what were to become Fluxus event scores date back to John Cage's famous class at The New School, where artists such as George Brecht, Al Hansen, Allan Kaprow, and Alison Knowles began to create art works and performances in musical form. One of these forms was the event. Events tend to be scored in brief verbal notations. These notes are known as event scores. In a general sense, they are proposals, propositions, and instructions. Thus, they are sometimes known as proposal pieces, propositions, or instructions. The first collections of Fluxus event scores were the working sheets for Fluxconcerts. They were generally used only by the artist-performers who were presenting the work. With the birth of Fluxus publishing, however, collections of event scores soon came to take three forms. The first form was the boxed collection. These were individual scores written or printed on cards. The classic example of this boxed collection is George Brecht's Water Yam. A second format was the book or pamphlet collection of scores, often representing work by a single artist. Yoko Ono's Grapefruit is probably the best known of these collections. Now forgotten, but even more influential during the 1960s, were the small collections that Dick Higgins published in the Something Else Press pamphlet series under the Great Bear imprint. These small chapbooks contained work by Bengt af Klintberg, Alison Knowles, Nam June Paik, and many other artists working in the then-young Fluxus and intermedia traditions. -

52 Events 2002

52 Events 2002 Ken Friedman 52 Events 2002 Ken Friedman Edition of 250 signed and numbered diaries. This is number . Published by Show and Tell Editions (Heart Fine Art Ltd.) 1 Royal Mile Mansions, 50 North Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1QN Scotland,United Kingdom Tel/Fax: (+44) 131 225 8217 www.heartfineart.com mail@ heartfineart.com In August of 1966, Dick Higgins looked George explained to me that these at an object I made. This was one of things ought to be written down. Th e the philosophical objects and form in which George suggested I write enactments I had been undertaking them was the event score. He wanted to since I was a boy in New London, publish the complete collection of my Connecticut. I never had a name for events up to the time we met. I did not them, and I thought I was quite alone in call them events until 1966. George doing these kinds of things until I gave me the name, and showed me how encountered the books of Something to score these thoughts, actions, and Else Press. Those books led me to works so that others could realise them. Dick, and Dick sent me to George Maciunas. While George announced the publication of my collected event scores George liked the object and decided to several times, he never produced them. publish it. This was the Open and Shut I kept writing the scores. From 1966, Case, my first Fluxus multiple, these scores were published and published in the early autumn of 1966. circulated in different forms and At our first meeting, George peppered editions, and exhibited. -

Conceptual Art, Experimental Literature

We specialize in RARE JOURNALS, PERIODICALS and MAGAZINES Please ask for our Catalogues and come to visit us at: http://antiq.benjamins.com CONCEPTUAL VISUAL POETRY ART, rare PERIODIcAlS cNO ceptual art, Experimental literature, visual poetry, etc. Search from our Website for Unusual, Rare, part I: A-l Obscure - complete sets and special issues of journals, in the best possible condition. Avant Garde Art Documentation Concrete Art Fluxus Visual Poetry Small Press Publications Little Magazines Artist Periodicals De-Luxe editions CAT. Beat Periodicals 302 Underground and Counterculture and much more Catalogue No. 302 (2019) JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT Visiting address: Klaprozenweg 75G · 1033 NN Amsterdam · The Netherlands Postal address: P.O. BOX 36224 · 1020 ME Amsterdam · The Netherlands tel +31 20 630 4747 · fax +31 20 673 9773 · [email protected] JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT B.V. AMSTERDAM CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Prices in this catalogue are indicated in EUR. Payment and billing in US-dollars to the Euro equivalent is possible. 2. All prices are strictly net. For sales and delivery within the European Union, VAT will be charged unless a VAT number is supplied with the order. Libraries within the European Community are therefore requested to supply their VAT-ID number when ordering, in which case we can issue the invoice at zero-rate. For sales outside the European Community the sales-tax (VAT) will not be applicable (zero-rate). 3. The cost of shipment and insurance is additional. 4. Delivery according to the Trade Conditions of the NVvA (Antiquarian Booksellers Association of The Netherlands), Amsterdam, depot nr. 212/1982.