Current P SYCHIATRY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 7 Mood Disorders

An Overview of Mood Disorders • Gross Deviations in Mood • 2 Fundamental states: Depression & Mania Chapter 7 • Depression: “The Low” – Major Depressive Episode •The most commonly diagnosed & most severe Mood Disorders depression •Depressed (or in children, irritable) mood state that lasts at least 2 weeks –Cognitive symptoms •Feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt •Diminished ability to concentrate or indecisiveness – Dysthymic Disorder –Disturbed physical functions (vegetative •Similar symptoms to Major Depressive Episode, symptoms) (central to the disorder) but milder •Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day –Also fewer symptoms: need only 2 of the •Significant weight loss or gain or change in symptoms, as opposed to 5 in Major Depressive appetite Episode •Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day •A persistently depressed (or, in children & •Psychomotor agitation or retardation adolescents, irritable) mood that continues for at –Nearly always accompanied by markedly least 2 years diminished interest or ability to experience pleasure –During those 2 years, the individual has never been (anhedonia) from life without the symptoms for more than 2 months at a • Average duration if untreated: 9 months time •Most people with Dysthymia eventually experience a major depressive episode • Mania: “The High” –Abnormally exaggerated elation, joy, or euphoria OR irritability (common toward the –Behavioral symptoms end of the episode) lasting at least 1 week •More talkative / pressured speech –Cognitive symptoms •Psychomotor agitation -

Life with Bipolar Fact Sheet.Pdf

Being so scared Having so Trying to You do not Exhilarating. You you’remisunderstood paralyzed much energy catch up to want the finally feel like that you stress your own high of the you’re normal, out your mind mind mania to until the anger and your body end; then sets in An amazing after the feeling that high of the leads to feeling Things are mania is horrible going You have no over, the Difficult to tell if great and inhibitions, and lows set in you can trust your it’s scary consequences and reality own perception because don’t apply to becomes a of reality You feel you know what you do problem everything at it will not once and then stay that you are numb way to the world Being on a see-saw Flipping a The of human emotion switch in future your mind “Normal” quickly people are goes Mania is speed. from annoying You must start and Being constantly in bright because finish everything activities that take up to you’ll never Productive, now—you can’t time with hardly any carefree, bleak have that stop moving results or satisfation and then stability exhausting Busy brain, When the mania busy Unending back burns out, you’ve senses, and forth with got nothing left Frightening to be so out of busy libido yourself in you control and off-balance Share what life with bipolar disorder feels like for you in words, images or video by tagging your social media posts with #mentalillnessfeelslike. Posts will be displayed at mentalhealthamerica.net/feelslike where you can also submit anonymously if you choose. -

Children's Mental Health Disorder Fact Sheet for the Classroom

1 Children’s Mental Health Disorder Fact Sheet for the Classroom1 Disorder Symptoms or Behaviors About the Disorder Educational Implications Instructional Strategies and Classroom Accommodations Anxiety Frequent Absences All children feel anxious at times. Many feel stress, for example, when Students are easily frustrated and may Allow students to contract a flexible deadline for Refusal to join in social activities separated from parents; others fear the dark. Some though suffer enough have difficulty completing work. They worrisome assignments. Isolating behavior to interfere with their daily activities. Anxious students may lose friends may suffer from perfectionism and take Have the student check with the teacher or have the teacher Many physical complaints and be left out of social activities. Because they are quiet and compliant, much longer to complete work. Or they check with the student to make sure that assignments have Excessive worry about homework/grades the signs are often missed. They commonly experience academic failure may simply refuse to begin out of fear been written down correctly. Many teachers will choose to Frequent bouts of tears and low self-esteem. that they won’t be able to do anything initial an assignment notebook to indicate that information Fear of new situations right. Their fears of being embarrassed, is correct. Drug or alcohol abuse As many as 1 in 10 young people suffer from an AD. About 50% with humiliated, or failing may result in Consider modifying or adapting the curriculum to better AD also have a second AD or other behavioral disorder (e.g. school avoidance. Getting behind in their suit the student’s learning style-this may lessen his/her depression). -

Schizoaffective Disorder?

WHAT IS SCHIZOAFFECTIVE DISORDER? BASIC FACTS • SYMPTOMS • FAMILIES • TREATMENTS RT P SE A Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center E C I D F I A C VA Desert Pacific Healthcare Network V M R E E Long Beach VA Healthcare System N T T N A E L C IL L LN A E IC S IN Education and Dissemination Unit 06/116A S R CL ESE N & ARCH, EDUCATIO 5901 E. 7th street | Long Beach, CA 90822 basic facts Schizoaffective disorder is a chronic and treatable psychiatric Causes illness. It is characterized by a combination of 1) psychotic symp- There is no simple answer to what causes schizoaffective dis- toms, such as those seen in schizophrenia and 2) mood symptoms, order because several factors play a part in the onset of the dis- such as those seen in depression or bipolar disorder. It is a psychi- order. These include a genetic or family history of schizoaffective atric disorder that can affect a person’s thinking, emotions, and be- disorder, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder, biological factors, en- haviors and can impact all aspects of daily living, including work, vironmental stressors, and stressful life events. school, social relationships, and self-care. Research shows that the risk of schizoaffective disorder re- Schizoaffective disorder is considered a psychotic disorder sults from the influence of genes acting together with biological because of its prominent features of hallucinations and delusions. and environmental factors. A family history of schizoaffective dis- Therefore, people with this illness have periods when they have order does not necessarily mean children or other relatives will difficulty understanding the reality around them. -

Racing and Crowded Thoughts in Mood Disorders: a Data-Oriented Theoretical Reappraisal Gilles Bertschy, Sebastien Weibel, Anne Giersch, Luisa Weiner

Racing and crowded thoughts in mood disorders: A data-oriented theoretical reappraisal Gilles Bertschy, Sebastien Weibel, Anne Giersch, Luisa Weiner To cite this version: Gilles Bertschy, Sebastien Weibel, Anne Giersch, Luisa Weiner. Racing and crowded thoughts in mood disorders: A data-oriented theoretical reappraisal. L’Encéphale, Elsevier Masson, 2020, 46 (3), pp.202-208. 10.1016/j.encep.2020.01.007. hal-02935003 HAL Id: hal-02935003 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02935003 Submitted on 15 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Review of the literature Racing and crowded thoughts in mood disorders: A data-oriented theoretical reappraisal Tachypsychie dans les troubles de l’humeur : une réévaluation théorique basée sur les données de la littérature a,b,c, a,b b a,d,e G. Bertschy ∗ , S. Weibel , A. Giersch , L. Weiner a Pôle de psychiatrie, santé mentale & addictologie des hôpitaux universitaires de Strasbourg, 67000 Strasbourg, France b Inserm U1114, 67000 Strasbourg, France c Fédération de médecine translationnelle de Strasbourg, université de Strasbourg, 67000 Strasbourg, France d Laboratoire de psychologie des cognitions, 67000 Strasbourg, France e Faculté de psychologie, université de Strasbourg, 67000 Strasbourg, France a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Objectives. -

Racing Thoughts: What to Consider

Pearlsearls Racing thoughts: What to consider Theodore J. Wilf, MD Dr. Wilf is a Consultant Psychiatrist, Table Warren E. Smith Health Centers, ave you ever had times in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. your life when you had a tremen- Causes of racing thoughts Disclosure dous amount of energy, like too Medications and illicit drugs The author reports no financial H much energy, with racing thoughts? relationships with any companies Amphetamines whose products are mentioned in I initially ask patients this question Methylphenidate this article, or with manufacturers when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Dexamethasone of competing products. Cocaine Some patients insist that they have rac- Phencyclidine ing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a Medical disorders rate faster than they can be expressed 1 Stroke through speech —but not episodes of Traumatic brain injury hyperactivity. This response suggests Multiple sclerosis that some patients can have racing Cushing’s disease thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar Source: Reference 1 disorder. Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and Other potential causes treatment. When untreated, a patient’s Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a racing thoughts may range from a mild diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety disturbance lasting a few days to a more could cause racing thoughts that do not severe disturbance occurring daily. In this require treatment with a mood stabilizer article, I suggest treatments that may help or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe about having panic attacks or experience possible causes that include, but are not severe chronic stress may have racing limited to, mood disorders. -

The Implications of Hypersomnia in the Context of Major Depression: Results from a Large, International, Observational Study

European Neuropsychopharmacology (2019) 29, 471–481 www.elsevier.com/locate/euroneuro The implications of hypersomnia in the context of major depression: Results from a large, international, observational study a a, b c a A. Murru , G. Guiso , M. Barbuti , G. Anmella , a, d ,e a ,f , g g h N. Verdolini , L. Samalin , J.M. Azorin , J. Jules Angst , i j k a, l C.L. Bowden , S. Mosolov , A.H. Young , D. Popovic , m c a, ∗ a M. Valdes , G. Perugi , E. Vieta , I. Pacchiarotti , For the BRIDGE-II-Mix Study Group a Barcelona Bipolar and Depressive Disorders Unit, Institute of Neuroscience, Hospital Clinic, University of Barcelona, IDIBAPS, CIBERSAM, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain b Clinica Psichiatrica, Dipartimento di Igiene e Sanità, Università di Cagliari, Italy c Division of Psychiatry, Clinical Psychology and Rehabilitation, Department of Medicine, University of Perugia, Santa Maria della Misericordia Hospital, Edificio Ellisse, 8 Piano, Sant’Andrea delle Fratte, 06132, Perugia, Italy d FIDMAG Germanes Hospitalàries Research Foundation, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain e Division of Psychiatry, Clinical Psychology and Rehabilitation, Department of Medicine, Santa Maria della Misericordia Hospital, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy f CHU Clermont-Ferrand, Department of Psychiatry, University of Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France g Fondation FondaMental, Hôpital Albert Chenevier, Pôle de Psychiatrie, Créteil, France h Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Psychiatric Hospital, University of Zurich, Zurich, -

Facts About Schizoaffective Disorder

FACTS ABOUT SCHIZOAFFECTIVE DISORDER What Is Schizoaffective Disorder? Schizoaffective disorder is a major psychiatric disorder that is quite similar to schizophrenia. The disorder can affect all aspects of daily living, including work, social relationships, and self-care skills (such as grooming and hygiene). People with schizoaffective disorder can have a wide variety of different symptoms, including having unusual perceptual experiences (hallucinations) or beliefs others do not share (delusions), mood (such as marked depression), low motivation, inability to experience pleasure, and poor attention. The serious nature of the symptoms of schizoaffective disorder sometimes requires consumers to go to the hospital to get care. The experience of schizoaffective disorder can be described as similar to "dreaming when you are wide awake"; that is, it can be hard for the person with the disorder to distinguish between reality and fantasy. How Common Is Schizoaffective Disorder? About one in every two hundred people (1/2 percent) develops schizoaffective disorder at some time during his or her life. Schizoaffective disorder, along with schizophrenia, is one of the most common serious psychiatric disorders. More hospital beds are occupied by persons with these disorders than any other psychiatric disorder. However, as with other types of mental illness, individuals with schizoaffective disorder can engage in treatment and other mental health recovery efforts that have the potential to dramatically improve the well being of the individual. How Is the Disorder Diagnosed? Schizoaffective disorder can only be diagnosed by a clinical interview. The purpose of the interview is to determine whether the person has experienced specific "symptoms" of the disorder, and whether these symptoms have been present long enough to merit the diagnosis. -

Measuring Racing Thoughts in Healthy Individuals: the Racing and Crowded Thoughts Questionnaire (RCTQ)

Comprehensive Psychiatry 82 (2018) 37–44 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Comprehensive Psychiatry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/comppsych Measuring racing thoughts in healthy individuals: The Racing and Crowded Thoughts Questionnaire (RCTQ) Luisa Weiner a,b,⁎, Sébastien Weibel a,b,WagnerdeSousaGurgelc, Ineke Keizer d,MarianneGex-Fabryd, Anne Giersch a, Gilles Bertschy a,b,e a INSERM U1114, Strasbourg, France b Psychiatry Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg, France c Institute of Psychiatry (IPq), University of São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil d Department of Mental Health and Psychiatry, University Hospitals of Geneva, Switzerland e Translational Medicine Federation, University of Strasbourg, France article info abstract Available online xxxx Racing thoughts refer to an acceleration and overproduction of thoughts, which have been associated with manic Keywords: and mixed episodes. Phenomenology distinguishes ‘crowded’ from ‘racing’ thoughts, associated with mixed Racing thoughts depression and mania, respectively. Recent data suggest racing thoughts might also be present in healthy individ- Crowded thoughts uals with sub-affective traits and symptoms. We investigated this assumption, with a 34-item self-rating scale, Affective temperament the Racing and Crowded Thoughts Questionnaire (RCTQ), and evaluated its reliability, factor structure, and Cyclothymia concurrent validity. 197 healthy individuals completed the RCTQ, the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Thought overactivation – Distractibility Pisa, Paris, and San Diego autoquestionnaire (TEMPS-A), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Altman Self-Rating Mania scale (ASRM), and the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS). Exploratory factor analysis yielded a three-factor solution, labeled ‘thought overactivation’, ‘burden of thought overactivation’,and‘thought overexcitability’. Internal consistency of each of the three subscales of the RCTQ was excellent. -

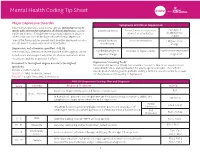

Mental Health Coding Tip Sheet

Mental Health Coding Tip Sheet Major Depressive Disorder Symptoms of Clinical Depression Patients that experience a depressive episode lasting two or more weeks with at least five symptoms of clinical depression causing *Depressed Mood *Loss of interest or pleasure Feelings of significant distress or impairment not aused by substance abuse or in most or all activities worthlessness other condityion that can be diagnosed with clinical depression.1 or guilt *One of the five symptoms present must be either depressed mood or Suicidal ideations Poor concentration Fatigue or low loss of interest or pleasure in most or all activities. or self-harm energy Depression, not otherwise specified - F32.92 The condition is often more severe than the code suggests. Avoid Significant weight or Insomnia or hypersomnia Psychomotor retardation broad terms and unspecified codes for a better awareness about appetite change or agitation the disease and the population it affects. 3 Document to the highest degree & code to the highest Depression Screening Tools Mental Health America (MHA) has a number resources that focus on prevention, specificity early identification, and intervention for adults age 18 and older. The PHQ-9© Include condition details questionnaire4 can be given to patients during a primary care encounter to screen SEVERITY - Mild, Moderate, Severe for the presence and severity of depression. EPISODE - Single, Recurrent, In Remission PHQ-9© Depression Scoring, Plan and Diagnosis Score Severity Proposed Treatment ICD-10 None: not depressed/no personal history of depression. N/A 0 - 4 None - Minimal In Remission*: patient is receiving treatment for depression but condition is stable and See Below symptoms no longer meet criteria for major depression. -

Psychological Effects of Sleep Deprivation Sleep and Mental Health Sleep and Mental Health Are Closely Connected

Wellness Tips To Better Your Life May 2019 Sleep Optimization Vol 2, Issue 5 MENTAL HEALTH MONTH Psychological Effects of Sleep Deprivation Sleep and mental health Sleep and mental health are closely connected. Sleep deprivation affects your lifestyle changes psychological state and mental health. And those with mental health problems are more likely to have insomnia or other sleep disorders. Sleep problems are In some respects, the treatment particularly common in patients with anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and recommended for the most common attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). sleep problem, insomnia, is the same for all patients, regardless of whether they Depression. Studies using different methods and populations estimate that 65% to also suffer from psychiatric disorders. 90% of adult patients with major depression, and about 90% of children with this disorder, experience some kind of sleep problem. The fundamentals are a combination of lifestyle changes, behavioral strategies, Insomnia and other sleep problems affect outcomes for psychotherapy, and drugs if necessary. patients with depression. Studies report that depressed patients who continue to experience insomnia are less Lifestyle changes. Most people know likely to respond to treatment than those without sleep that caffeine contributes to sleeplessness, problems. but so can alcohol and nicotine. Giving up these substances is best, but avoiding Bipolar disorder. Studies in different populations them before bedtime is another option. report that 69% to 99% of patients experience insomnia or report less need for sleep during a manic episode of bipolar disorder. In bipolar depression, however, studies Physical activity. Regular aerobic report that 23% to 78% of patients sleep excessively (hypersomnia), while others activity helps people fall asleep faster, may experience insomnia or restless sleep. -

Depression an Information Guide Revised Edition

Depression An information guide revised edition Christina Bartha, MSW, RSW Carol Parker, MSW, RSW Cathy Thomson, MSW, RSW Kate Kitchen, MSW, RSW Depression An information guide revised edition Christina Bartha, MSW, RSW Carol Parker, MSW, RSW Cathy Thomson, MSW, RSW Kate Kitchen, MSW, RSW Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Depression : an information guide / Christina Bartha, Carol Parker, Cathy Thomson, Kate Kitchen. -- Revised edition. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN: 978-1-77052-571-9 (PRINT) ISBN: 978-1-77052-572-6 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-77052-573-3 (HTML) ISBN: 978-1-77052-574-0 (ePUB) 1. Depression, Mental--Popular works. I. Bartha, Christina, author II. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body RC537.D456 2013 616.85’27 C2013-905654-8 C2013-905655-6 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2008, 2013 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alternate formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : La dépression : Guide d’information This guide was produced by CAMH’s Knowledge and Innovation Support Unit.