The Rhyme That Remains: Towards a Populist Poetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slang in American and British Hip-Hop/Rap Song Lyrics

LEXICON Volume 5, Number 1, April 2018, 84-94 Slang in American and British Hip-Hop/Rap Song Lyrics Tessa Zelyana Hidayat*, Rio Rini Diah Moehkardi Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research examines semantic changes and also the associative patterns of slang, focusing primarily on common topics, i.e., people and drugs. The data were slang terms taken from the lyrics of hip-hop/rap songs sung by four singers, two from the U.S.A and two from the U.K. A total of 105 slang terms were found, 45 of which belong to the people category and 16 to the drugs category in the American hip-hop/rap song lyrics, and in the British hip-hop/rap song lyrics, 26 of which belong to the people category and 18 to the drugs category. Bitch and nigga were found to be the most frequently used slang terms in the people category. In terms of semantic changes, broadening, amelioration, and narrowing were found, and in terms of associative patterns, effect, appearance, way of consuming, constituent, and container associative patterns were found. In addition, a new associative pattern was found, i.e., place of origin. Keywords: associative patterns, people and drugs slang, semantic change, slang. mislead people outside their group. Then, the INTRODUCTION usage of Cant began to slowly develop. Larger “This party is just unreal!” Imagine a person groups started to talk Cant in their daily life. It saying this sentence in the biggest New Year’s Eve was even used for entertainment purposes, such as party in his/her town, with the largest crowd, the in literature. -

From Page to Stage (Or Movie Or Song) Shakespeare’S Plays Were Meant to Be Performed (Heard) Rather Than Read

From Page to Stage (or Movie or Song) Shakespeare’s plays were meant to be performed (heard) rather than read. Shakespeare is daunting! We suggest that students read one scene, break down the scene and then view the scene from a filmed version. Make sure to preview the filmed versions and check ratings for age appropriateness. Examples: Richard III: Richard III staring and directed by Laurence Olivier, 1955; Richard III with Ian McKellan, 1995; Looking for Richard with Al Pacino, 1996. Hamlet: Hamlet with Laurence Olivier, 1948; Hamlet with Mel Gibson, 1990; Rosencranz and Guildenstern are Dead by Tom Stoppard, 1996; Hamlet with Kenneth Branagh, 1996. Macbeth: Throne of Blood by Akira Kurosawa, 1957; Macbeth by Roman Polanski, 1973. Romeo and Juliet: West Side Story, 1961; Romeo and Juliet by Franco Zeffirelli, 1968; Romeo + Juliet by Baz Lurman, 1968; Shakespeare in Love, 1999. A Midsummer Night’s Dream: A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Peter Hall,1968; A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Michael Hoffman with Kevin Kline and Michelle Pfeiffer, 1999 Likewise, Hip Hop is meant to be heard rather than read. Most Hip Hop songs tell a story. Ask students to bring in their favorite Hip Hop songs with accompanying lyrics. Distribute the lyrics to the class and talk about the story. Then listen to the selection with music and discuss how the music contributes to the artistry of the piece. (Note: You may want to specify that students bring radio versions of songs and pre-screen for content and language.) Love I start to think, and then I sink Tryin to find -

That World of Somewhere in Between: the History of Cabaret and the Cabaret Songs of Richard Pearson Thomas, Volume I

That World of Somewhere In Between: The History of Cabaret and the Cabaret Songs of Richard Pearson Thomas, Volume I D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebecca Mullins Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2013 D.M.A. Document Committee: Dr. Scott McCoy, advisor Dr. Graeme Boone Professor Loretta Robinson Copyright by Rebecca Mullins 2013 Abstract Cabaret songs have become a delightful and popular addition to the art song recital, yet there is no concise definition in the lexicon of classical music to explain precisely what cabaret songs are; indeed, they exist, as composer Richard Pearson Thomas says, “in that world that’s somewhere in between” other genres. So what exactly makes a cabaret song a cabaret song? This document will explore the topic first by tracing historical antecedents to and the evolution of artistic cabaret from its inception in Paris at the end of the 19th century, subsequent flourish throughout Europe, and progression into the United States. This document then aims to provide a stylistic analysis to the first volume of the cabaret songs of American composer Richard Pearson Thomas. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to the person who has been most greatly impacted by its writing, however unknowingly—my son Jack. I hope you grow up to be as proud of your mom as she is of you, and remember that the things in life most worth having are the things for which we must work the hardest. -

Messenger “Advent, Justice, and a Release from the Random” by David Pettit

February/March 2020 Messenger “Advent, Justice, and a Release from the Random” by David Pettit We’ve all seen the stories and the videos on social media. The police officer who pulls someone over in a sketchy neighborhood, and to the stressed and confused driver, the police officer hands a turkey or a check just in time for the holidays. Or the billionaire commencement speaker who cancels the stu- dent debt of that lucky graduating class. Or the fortunate couple for whom Ellen decides to give a new home, their shock, and elation a form of public entertainment. Random acts of kindness. As random as the lottery. As random as a school shooting. Always guessing. Wondering. No rhyme or reason. I’m told that such acts of kindness are a reminder that there are good people out there. There is good in humanity still. And to a limited degree, I can subscribe to this. I certainly don’t want to discourage bold acts to help others. But randomness; it has an effect on the psyche. Always wondering, nothing to count on. Randomness. A loose synonym for inequality, for haphazardness, luck, fortune, or misfortune. It was this past Advent that I listened to an audio copy of The Tattooist of Auschwitz. I was drawn into the world and the experiences it presented, as any skillfully told story can do, causing me to see the world through its perspective. I saw randomness. The cumulative effect of being vulnerable to whims, caprices, and power, always wondering what response will come. What will happen? Extra food ra- tion? The butt of a rifle to the head? A bullet? Random. -

No Rhyme Or Reason Arbon Tracker

Initiative No Rhyme or Reason arbon Tracker Unreasonable projections in a world confronting climate change Carbon Tracker Initiative, July 2016 About Carbon Tracker The Carbon Tracker Initiative is a team of financial specialists making climate risk real in today’s financial markets. Our research to date on unburnable carbon and stranded assets has started a new debate on how to align the financial system with the energy transition to a low carbon future. This report was authored by: Rob Schuwerk and Luke Sussams. Acknowledgements This report draws heavily on internal memoranda prepared and commissioned by John Wunderlin on behalf of Carbon Tracker. The authors would also like to acknowledge the contributions of James Leaton, Mark Fulton, Tom Drew and Stefano Ambrogi for review and edits; Margherita Gagliardi for the design. Disclaimer Carbon Tracker is a non-profit company set-up to produce new thinking on climate risk. The organisation is funded by a range of European and American foundations. Carbon Tracker is not an investment adviser, and makes no representation regarding the advisability of investing in any particular company or investment fund or other vehicle. A decision to invest in any such investment fund or other entity should not be made in reliance on any of the statements set forth in this publication. While the organisations have obtained information believed to be reliable, they shall not be liable for any claims or losses of any nature in connection with information contained in this document, including but not limited to, lost profits or punitive or consequential damages. The information used to compile this report has been collected from a number of sources in the public domain and from Carbon Tracker licensors. -

They'll Be Crying in Their Beer

Friday, August 7, 2020 www.rivernewsonline.com Page 12 SPORTS THEY’LL BE CRYING IN THEIR BEER DIGEST GNC makes fall 2010 Rebels sports schedule stay hot, stun changes defending champ The Great Northern Confer - ence on Tuesday made a host of Kimberly for schedule changes to a number Legion state title of its fall sports as it prepares for Second in a series an abbreviated season in the wake of the COVID-19 pan - By Jeremy Mayo demic. The most drastic sched - RIVER NEWS SPORTS EDITOR ule changes took place in football, boys’ soccer and vol - By vanquishing one of its leyball — all of which had their most stubborn opponents in first days of practice pushed dominating fashion, defeat - back to Labor Day following a ing Merrill 14-0 in the first WIAA Board of Control decision round of the 2010 Wisconsin late last month. AA American Legion Base - Details are still to be deter - ball state tournament, the mined by the conference regard - Rhinelander Post 7 Rebels ing COVID protocols and atoned for games that had restrictions at events, and will slipped through their grasp be announced at a later date. during the regular season See RiverNewsOnline.com for and regional tournament, a rundown of the changes. setting up a chain of events BOB MAINHARDT ARCHIVES that would culminate four In this Aug. 3, 2010 photo, the Rhinelander Post 7 Rebels celebrate after recording the final out in the days later in a state champi - Wisconsin American Legion Class AA state tournament championship game against Kimberly at Athletic onship. -

A Wild Stab in the Dark: Exposing Eminem's Existentialism

A Wild Stab in the Dark: Exposing Eminem’s Existentialism Daniel Ragusa AS 112 “Encountering Unbelief” Due: 12/6 1 Abstract This paper attempts to apply the principles of covenantal apologetics to today’s cultural milieu by using the latest music album by American rapper, Eminem, as a gateway into today’s postmodern thinking. The worldview of Eminem developed in his latest album, The Marshal Mathers LP2 (2013), will be shown to have deep affinity with the atheistic existentialism of Friedrich Nietzsche, the father of postmodernism. This allows the philosophical thought of Nietzsche to penetrate today’s culture without anyone actually reading his books, but simply listening to its application in the lyrics of Eminem and other influential artists that espouse a fundamentally similar philosophy. After establishing Eminem’s worldview, there will be provided an internal critique of it in terms of its metaphysics, epistemology and ethics, as well as its inability to account for the one and the many. It will become evident that Eminem’s worldview is far from a coherent system and must either borrow capital from the Christian worldview or spiral into total absurdity. Introduction The average person today is not reading thick volumes of philosophy to establish his worldview, but he does have headphones on. Within the first two weeks of its release, Eminem’s latest album—The Marshall Mathers LP2 (2013)1—went platinum with over one million people purchasing it.2 The album is an amalgam of raw anger, unwavering resolve, and deep-felt despair masterfully merged into unprecedented lyrical brilliance. The devilish fantasies of MMLP2 survey a wide spectrum of depraved thinking. -

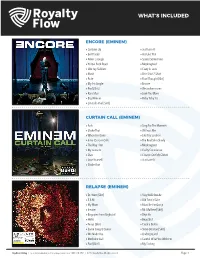

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

THE WRITING CENTER AS a SETTING for LEARNING to TUTOR DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment O

FROM TRAINING TO PRACTICE: THE WRITING CENTER AS A SETTING FOR LEARNING TO TUTOR DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Krista H. Stonerock, B.A., M.A ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Dr. George Newell, Adviser __________________________ Dr. Maia Pank-Mertz Adviser College of Education Dr. Anna Soter ABSTRACT Although tutorial programs have become key components of college freshmen writing programs, few studies have considered how students learn to tutor their peers. This study is a qualitative examination of a first-year writing tutorial program situated within a college writing center with a mission to ensure student retention in the college. In the tutorials, peer tutors consulted biweekly with basic writers throughout their first year of college. The peer tutors were trained in a three-week tutor training program designed to introduce them to both writing center theory and tutoring strategies which are aligned with the writing center mission and goals. Case study methods were used to consider the transfer of teaching tools from tutor training to the tutors’ practices in the writing conferences. Through an activity-theory analysis of tutor training sessions, audio-taped and transcribed conferences, field notes, observation-based interviews, and other data, the two tutors’ decision-making was interpreted as a function of their participation in tool- mediated action—both conceptual and practical—in a range of settings. The research employed ethnographic methods to follow the peer tutors through a three-week training program and a fifteen-week semester of tutoring. -

Secrets of a Successful Organizer

SECRETS OF A SUCCESSFUL ORGANIZER TRAINER’S GUIDE Adapted for the National Education Association Center for Organizing CHRIS BROOKS, SONIA SINGH, AND SAMANTHA WINSLOW LABOR NOTES l labornotes.org SECRETS OF A SUCCESSFUL ORGANIZER TRAINER’S GUIDE Adapted for the NEA Center For Organizing, June 2018 INTRODUCTION Trainer’s Guide Organizing at NEA The NEA—in response to the relentless threats to public education, public employees, students, and communities—is partnering with state and local affiliates to build an Association-wide culture of organizing. Our goal is to build on our legacy of advocacy and leading the professions, fight for our mission of great public schools for all students, and grow sustainable, strong NEA affiliates for the future. A culture of organizing is one that promotes deep member engagement, leadership development, and collective action. At its core, organizing means facilitating collective action among a group and empowering others to take on leadership roles. A culture of organizing is an intentional and strategic approach to the work of the Association: one that relies on data analytics, thoughtful planning, accountability, and continuous improvement. The NEA Center for Organizing measures successful organizing through multiple lenses: robust member engagement, effective distributive leadership structures, and growth in membership. We seek to build these capacities through organizing campaigns built around the issues important to our members. Many different organizing strategies can lead to success; nonetheless, all authentic organizing is accountable for measurable goals and outcomes. Above all, we believe in leading with vision and aspiration, accompanied by concrete programs and plans. Effective organizing—which is what we all strive for—should result in increased member engagement of significant numbers of educators, expanding leadership, and real wins in the policies and practices that impact our members, our schools, our students and our communities—grounded in our values of equity, opportunity, and racial justice. -

Parking Pass Prices Increase While Availability to Students Decreases

Tuesday, August 28, 2018 ǀ Volume 137 ǀ Issue 1 ǀ Reaching students, faculty, and staff of the University of North Dakota since 1888 Inside this issue Urban Meyer 3 Power of One 5 For more content 8 visit www.dakotastudent.com Football /dakotastudent /DakotaStudent @dakotastudent PARKING PANDEMONIUM Parking pass prices increase while availability to students decreases Missy Iio / Dakota Student UND parking leaves students with less time in the classroom and more time looking for a place to park. Madison Feltman for students who live both on and off campus. Dakota Student Over the summer, dras- "There's too little parking for the tic changes were made to The beginning of the the parking here at UND volume of students either living on 2018-2019 academic both positive and nega- year also marks the sale tive. On the lighter side campus or commuting to campus" of parking permits for of things, new lots were the impending semes- constructed and existing ters. Parking has always Amber Rene, UND Student lots were stripped and been considered a hot repaved such as the lot topic here at UND. In south of Columbia Hall. out on a bad foot with ing more money versus students are forced into past years, space was al- On one hand, UND students this academic making life easier for the parking in an overflow ways considered limited parking services started year when they increased students paying tuition” lot. This lot is farther their prices from $155 to senior Amber Rene said. away and can cause a po- $190 for an off-campus “There's too little park- tential danger to students student permit. -

Fearlessness the Seventh Element of Drama

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2011 Fearlessness The Seventh Element Of Drama Matt Wenge University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Wenge, Matt, "Fearlessness The Seventh Element Of Drama" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1990. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1990 FEARLESSNESS: THE SEVENTH ELEMENT OF DRAMA by MATT WENGE B.A. Augustana College, 1997 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the department of Theater in the college of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2011 ABSTRACT Aristotle proclaimed in his Poetics that there were six elements to drama: spectacle, music, diction, thought, character, and plot. This paper will analyze the play Thom Pain (based on nothing) against these six elements. I will discuss the aspects of each element that are present in the show as well as the ideas and concepts my director, Tad Ingram, and I brought to the show. Through the rehearsal and performance process I discovered a seventh element; the element of fearlessness. In his Poetics, Aristotle does not fully address what the actor brings to the performance and this aspect is just as important as what the script and staging bring to the performance.