Picturing the Artist's Wife, a Comparative Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Essay: Grappling with “Big Painting”: Akela Reason‟S Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History

Review Essay: Grappling with “Big Painting”: Akela Reason‟s Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History Adrienne Baxter Bell Marymount Manhattan College Thomas Eakins made news in the summer of 2010 when The New York Times ran an article on the restoration of his most famous painting, The Gross Clinic (1875), a work that formed the centerpiece of an exhibition aptly named “An Eakins Masterpiece Restored: Seeing „The Gross Clinic‟ Anew,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.1 The exhibition reminded viewers of the complexity and sheer gutsiness of Eakins‟s vision. On an oversized canvas, Eakins constructed a complex scene in an operating theater—the dramatic implications of that location fully intact—at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. We witness the demanding work of the five-member surgical team of Dr. Samuel Gross, all of whom are deeply engaged in the process of removing dead tissue from the thigh bone of an etherized young man on an operating table. Rising above the hunched figures of his assistants, Dr. Gross pauses momentarily to describe an aspect of his work while his students dutifully observe him from their seats in the surrounding bleachers. Spotlights on Gross‟s bloodied, scalpel-wielding right hand and his unnaturally large head, crowned by a halo of wiry grey hair, clarify his mastery of both the vita activa and vita contemplativa. Gross‟s foil is the woman in black at the left, probably the patient‟s sclerotic mother, who recoils in horror from the operation and flings her left arm, with its talon-like fingers, over her violated gaze. -

The Gross Clinic, the Agnew Clinic, and the Listerian Revolution

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles Department of Surgery 11-1-2011 The Gross clinic, the Agnew clinic, and the Listerian revolution. Caitlyn M. Johnson, B.S. Thomas Jefferson University Charles J. Yeo, MD Thomas Jefferson University Pinckney J. Maxwell, IV, MD Thomas Jefferson University Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/gibbonsocietyprofiles Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Surgery Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Johnson, B.S., Caitlyn M.; Yeo, MD, Charles J.; and Maxwell, IV, MD, Pinckney J., "The Gross clinic, the Agnew clinic, and the Listerian revolution." (2011). Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles. Paper 33. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/gibbonsocietyprofiles/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles yb an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. Brief Reports Brief Reports should be submitted online to www.editorialmanager.com/ amsurg.(Seedetailsonlineunder‘‘Instructions for Authors’’.) They should be no more than 4 double-spaced pages with no Abstract or sub-headings, with a maximum of four (4) references. -

October 2017

The Monthly Newsletter of the Philadelphia Sketch Club Gallery hours: Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday: 1 PM to 5 PM October 2017 Michelle Lockamy This Month’s Portfolio Reminder: It’s never too late. You can always renew your membership The Sketch Club’s 157th Anniversary Gala 2 You may pay online at http://sketchclub.org/annual- Support the Sketch Club 5 dues-payment/ Membership 8 or mail your check to: Sketch Club Activities 9 The Philadelphia Sketch Club Member Activities 11 235 S. Camac St. 2017 Main Gallery Schedule 12 2017 Stewart Gallery Schedule 15 Philadelphia, PA 19107 Sketch Club Open Workshop Schedule 16 For questions please contact the Gallery Manager at Art Natters: Members News 17 213335-545-9298 or email: Calls for Work and Notices 23 [email protected] Member Classifieds 25 Late Breaking News – See items that were submitted Call for Volunteers 26 after the publication date. Go to: Send your member news, announcements and corrections to [email protected] [email protected]. The deadline for ALL submissions The PSC general email is: info@sketchclub is 1-week before the end of the month. The Philadelphia Sketch Club - 235 South Camac Street - Philadelphia PA 19107 - 215-545-9298 A nonprofit organization under Chapter 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Page 1 The Monthly Newsletter of the Philadelphia Sketch Club Gallery hours: Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday: 1 PM to 5 PM October 2017 The Sketch Club’s 157th Anniversary Gala The Philadelphia Sketch Club’s 157th Anniversary Gala Please join us for our 157th Anniversary Gala on Saturday, October 21st. -

The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 Oil Painting by American Artist Thomas Eakins

Antisepsis and women in surgery 12 The Gross ClinicThe, byPharos Thomas/Winter Eakins, 2019 1875. Photo by Geoffrey Clements/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 oil painting by American artist Thomas Eakins. Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty images Don K. Nakayama, MD, MBA Dr. Nakayama (AΩA, University of California, San Francisco, Los Angeles, 1986, Alumnus), emeritus professor of history 1977) is Professor, Department of Surgery, University of of medicine at Johns Hopkins, referring to Joseph Lister North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC. (1827–1912), pioneer in the use of antiseptics in surgery. The interpretation fits so well that each surgeon risks he Gross Clinic (1875) and The Agnew Clinic (1889) being consigned to a period of surgery to which neither by Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) face each other in belongs; Samuel D. Gross (1805–1884), to the dark age of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in a hall large surgery, patients screaming during operations performed TenoughT to accommodate the immense canvases. The sub- without anesthesia, and suffering slow, agonizing deaths dued lighting in the room emphasizes Eakins’s dramatic use from hospital gangrene, and D. Hayes Agnew (1818–1892), of light. The dark background and black frock coats worn by to the modern era of aseptic surgery. In truth, Gross the doctors in The Gross Clinic emphasize the illuminated was an innovator on the vanguard of surgical practice. head and blood-covered fingers of the surgeon, and a bleed- Agnew, as lead consultant in the care of President James ing gash in pale flesh, barely recognizable as a human thigh. -

Caroline Peart, American Artist

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Humanities MOMENTS OF LIGHT AND YEARS OF AGONY: CAROLINE PEART, AMERICAN ARTIST 1870-1963 A Dissertation in American Studies by Katharine John Snider ©2018 Katharine John Snider Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2018 The dissertation of Katharine John Snider was reviewed and approved* by the following: Anne A. Verplanck Associate Professor of American Studies and Heritage Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Charles Kupfer Associate Professor of American Studies and History John R. Haddad Professor of American Studies and Popular Culture Program Chair Holly Angelique Professor of Community Psychology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the life of American artist Caroline Peart (1870-1963) within the context of female artists at the turn of the twentieth century. Many of these artists’ stories remain untold as so few women achieved notoriety in the field and female artists are a relatively new area of robust academic interest. Caroline began her formal training at The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts at a pivotal moment in the American art scene. Women were entering art academies at record numbers, and Caroline was among a cadre of women who finally had access to formal education. Her family had the wealth to support her artistic interest and to secure Caroline’s position with other elite Philadelphia-area families. In addition to her training at the Academy, Caroline frequently traveled to Europe to paint and she studied at the Academie Carmen. -

Before Zen: the Nothing of American Dada

Before Zen The Nothing of American Dada Jacquelynn Baas One of the challenges confronting our modern era has been how to re- solve the subject-object dichotomy proposed by Descartes and refined by Newton—the belief that reality consists of matter and motion, and that all questions can be answered by means of the scientific method of objective observation and measurement. This egocentric perspective has been cast into doubt by evidence from quantum mechanics that matter and motion are interdependent forms of energy and that the observer is always in an experiential relationship with the observed.1 To understand ourselves as in- terconnected beings who experience time and space rather than being sub- ject to them takes a radical shift of perspective, and artists have been at the leading edge of this exploration. From Marcel Duchamp and Dada to John Cage and Fluxus, to William T. Wiley and his West Coast colleagues, to the recent international explosion of participatory artwork, artists have been trying to get us to change how we see. Nor should it be surprising that in our global era Asian perspectives regarding the nature of reality have been a crucial factor in effecting this shift.2 The 2009 Guggenheim exhibition The Third Mind emphasized the im- portance of Asian philosophical and spiritual texts in the development of American modernism.3 Zen Buddhism especially was of great interest to artists and writers in the United States following World War II. The histo- ries of modernism traced by the exhibition reflected the well-documented influence of Zen, but did not include another, earlier link—that of Daoism and American Dada. -

Download 1 File

MASTERPIECES OF ART April 21 to September 4, 1962 SEATTLE WORLD'S FAIR Cover: PIERRE AUGUSTE RENOIR, French, 1841-1919 48. NEAPOLITAN GIRL'S HEAD LENT BY: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Adoline Van Home Bequest, 1945), Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Property of The Hilla von Rebay Foundation Copyright 1962 by Century 21 Exposition Inc. Seattle World's Fair Catalogue MASTERPIECES OF ART FINE ARTS PAVILION April 21 to September 4, 1962 SEATTLE WORLD'S FAIR April 21 to October 21, 1962 Original model of portion of Seattle World's Fair. Art building in left foreground. FOREWORD The "Masterpieces of Art" catalogue illustrates and describes one of the five exhibits which comprise the Fine Arts Exhibition at the Seattle World's Fair. The form and selection of this exhibit are the work of Dr. William M. Milliken, Director Emeritus of The Cleveland Museum of Art. These great works come from fifty-seven American museums; and from the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Toronto, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Louvre, Paris, the Tokyo National Museum, Japan, the Academia Sinica, Taiwan, Republic of China, and the National Museum of India. The loan of these priceless works is a measure of the importance of our Seattle World's Fair; but even more, the willingness to lend these works is a tribute of affection and esteem to Dr. Milliken himself, the dean of American museum directors. The Fine Arts Exhibition at the Seattle World's Fair comprises five main exhibits, each the responsibility of a leading authority in his field: "Master- pieces of Art," assembled by Dr. -

Book Reviews and Book Notes

BOOK REVIEWS AND BOOK NOTES Edited by LEONIDAS DODSON University of Pennsylvania Notable Women Of Pennsylvania. Edited by Gertrude B. Biddle and Sarah D. Lowrie. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1942, pp. 307. $3.00.) Many of the two hundred brief biographies here presented were as- sembled in 1926 by Mrs. J. Willis Martin and her sesquicentennial com- mittee. Printed in the Public Ledger, they were mounted at the direction of its editor, the late Cyrus H. K. Curtis, in a Book of Honor. Other biographies have been added, and from the sum those which form the collection were carefully selected. The first two sketches present Madame Printz, wife of Governor Printz, and her capable daughter, Armot Papegoya, and the last four, Maud Conyers Exley, physician; Christine Wetherill Stevenson, actress, playwright, and founder of the Philadelphia Art Alliance; Marion Reilly, dean of Bryn Mawr College; and Caroline Tyler Lea, organizer and supporter of projects for human welfare. Between the two periods represented is recorded the expanding sphere of women's activities. Here are pioneer housewives who became perforce the defenders of their families. Here are Mary Jemison and Frances Slocum, exhibiting strength of character in long captivity. Here are Madame Ferree, Esther Say Harris, Maria Theresa Homet, Susanna Wright, Anna Eve Weiser. Here are patriots and soldiers-Lydia Darragh, Margaret Corbin, Molly Pitcher. Here are mothers of famous children- Anne West Gibson, Frances Rose Benit. Here are early diarists- Elizabeth Drinker, Sarah Eve, Sally Wister. Here are philanthropists- Rebecca Gratz, Helen Fleisher. Here are engravers and painters-Anna C. and Sarah Peale, Emily Sartain, Anna Lea Merritt, Mary Cassatt, Florence Este, Alice Barber Stephens, Jessie Wilcox Smith. -

A Finding Aid to the Carlen Galleries, Inc., Records, 1775-1997, Bulk 1940-1986, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Carlen Galleries, Inc., Records, 1775-1997, bulk 1940-1986, in the Archives of American Art Catherine S. Gaines 2002 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Gift (1986), 1906-1986............................................................................. 5 Series 2: Loan (1988), 1937-1986......................................................................... 11 Series 3: Gift (2002), 1835-1992............................................................................ 13 Series 4: Loan (2002), -

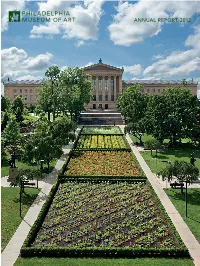

Annual Report 2012

BOARD OF TRUSTEES 4 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 6 A YEAR AT THE MUSEUM 8 Collecting 10 Exhibiting 20 Teaching and Learning 30 Connecting and Collaborating 38 Building 44 Conserving 50 Supporting 54 Staffing and Volunteering 62 CALENDAR OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 68 FINANCIAL StATEMENTS 72 COMMIttEES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 78 SUPPORT GROUPS 80 VOLUNTEERS 83 MUSEUM StAFF 86 A REPORT LIKE THIS IS, IN ESSENCE, A SNAPSHOT. Like a snapshot it captures a moment in time, one that tells a compelling story that is rich in detail and resonates with meaning about the subject it represents. With this analogy in mind, we hope that as you read this account of our operations during fiscal year 2012 you will not only appreciate all that has been accomplished at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but also see how this work has served to fulfill the mission of this institution through the continued development and care of our collection, the presentation of a broad range of exhibitions and programs, and the strengthening of our relationship to the com- munity through education and outreach. In this regard, continuity is vitally important. In other words, what the Museum was founded to do in 1876 is as essential today as it was then. Fostering the understanding and appreciation of the work of great artists and nurturing the spirit of creativity in all of us are enduring values without which we, individually and collectively, would be greatly diminished. If continuity—the responsibility for sustaining the things that we value most—is impor- tant, then so, too, is a commitment to change. -

Forrest House; Gaul-Forrest House

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 PHILADELPHIA SCHOOL OF DESIGN FOR WOMEN Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: PHILADELPHIA SCHOOL OF DESIGN FOR WOMEN Other Name/Site Number: Moore College of Art; Forrest House; Gaul-Forrest House 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 1346 North Broad Street Not for publication: City/Town: Philadelphia Vicinity: State: PA County: Philadelphia Code: 101 Zip Code: 19121 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private; X Building(s): X Public-local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal:__ Structure:__ Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 ____ buildings ____ ____ sites ___ ___ structures ____ ____ objects 1 _0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 PHILADELPHIA SCHOOL OF DESIGN FOR WOMEN Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Ben Franklin Parkway and Independence Mall Patch Programs

Ben Franklin Parkway and Independence Mall Patch Programs 1 Independence Mall Patch Program Introduction – Philadelphia’s History William Penn, a wealthy Quaker from London earned most of his income from land he owned in England and Ireland. He rented the land for use as farmland even though he could have made much more money renting it for commercial purposes. He considered the rent he collected from the farms to be less corrupt than commercial wealth. He wanted to build such a city made up of farmland in Pennsylvania. As soon as William Penn received charter for Pennsylvania, Penn began to work on his dream by advertising that he would establish, “ A large Towne or City” on the Delaware River. Remembering the bubonic plague in London (1665) and the disastrous fire of 1666, Penn wanted, “ A Greene county Towne, which would never be burnt, and always be wholesome.” In 1681, William Penn announced he would layout a “Large Towne or City in the most convenient place upon the river for health and navigation.” Penn set aside 10,000 acres of land for the Greene townie on the Delaware and he stretched the town to reach the Schuylkill so that the city would face both rivers. He acquired one mile of river frontage on the Schuylkill parallel to those on the Delaware. Thus Philadelphia became a rectangle 1200 acres, stretching 2 miles in the length from east to west between the 3 rivers and 1 mile in the width North and South. William Penn hoped to create a peaceful city. When he arrived in 1682, he made a Great Treaty of Friendship with the Lenni Lenape Indians on the Delaware.