USAID Ridge to Reef Final Program Performance Report…May 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Report for World Migratory Bird Day 2021 Event in East Asian-Australasian Flyway

EAAFP WMBD2021Small Grant Application Form Report for World Migratory Bird Day 2021 Event in East Asian-Australasian Flyway 1 EAAFP WMBD 2021 Small Grant Application Form Date of Submission: May 20, 2021 1. EVENT INFORMATION 1.1 Contact Information Full Name EnP. Grace V. Villanueva Name of the organisation Misamis University,Philippines Name(s) of the division Misamis University Community Extension Program and/or position / Director Misamis University College of Maritime Education Type of the organisation - Academe Government/NGO/Private Sector/Other Email [email protected] Postal address H.T. Feliciano Street, Aguada, Ozamiz City, Philippines Office phone numbers 088-531 loc 135 (Your) Cell number (optional) 09163514058 Fax(optional) 521-0431 Fax 2917 Website(optional) https:www.mu.edu.ph Additional contact person For. Bobby B. Alaman (optional) Date of submission May 18, 2021 1.2 Event tile: Conservation of Wildlife Migratory Bird and Wetland Areas in Misamis Occidental, Philippines through Advocacy and Capacity Development 1.3 Event Location - Where did your event take place? Name of country Philippines Name of city Ozamiz City Name of event place/venue Installation of CEPA Billboards- Barangay Migpange, Bonifacio, Misamis Occidental, Barangay Mantic, Tangub City and Poblacion, Sinacaban, Misamis Occidental, Municipalities of Plaridel and Baliangao Posting of CEPA Posters- 25 coastal barangays within Misamis Occidental. Virtual Lecture –Workshop hosted by Misamis University held at MUCEP Office, Misamis University, Ozamiz City via Zoom Celebration of WMBD 2021 Coastal Clean Up and Bird Watching – Barangay Mialen, Clarin, Misamis Occidental 2 EAAFP WMBD 2021 Small Grant Application Form 1.4 Event Type - Check the relevant categories of your event type Public awareness activity – local and/or national / Field Trip (e.g. -

Ozamis (City) Panaon Plaridel Sapang Dalag

Item Indicators Aloran Baliangao Bonifacio Clarin Jimenez Lopez Jaena Orquieta (city) Ozamis (city) Panaon Plaridel Sapang Dalaga Sinacaban Tangub (city) Tudela 1.1 M/C Fisheries Ordinance Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.2 Ordinance on MCS No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes No No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.3a Allow Entry of CFV No No No No No No No No No No report submitted N/A No N/A No 1.3b Existence of Ordinance N/A No No Yes No No report submitted No N/A N/A N/A 1.4a CRM Plan Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.4b ICM Plan Yes Yes Yes No Yes No No No No report submitted Yes Yes Yes 1.4c CWUP Yes No No No No No No report submitted Yes No Yes 1.5 Water Delineation Yes Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.6a Registration of fisherfolk Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.6b List of org/coop/NGOs Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7a Registration of Boats Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7b Licensing of Boats Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.7c Fees for Use of Boats No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.8a Licensing of Gears Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.8b Fees for Use of Gears No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.9a Auxiliary Invoices No Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes No No report -

FIRST HONORS Name Name of High School Course GPA Lowest Grade Total Units Go, Philip Nathaniel T

LA SALLE UNIVERSITY La Salle St., Brgy. Aguada, Ozamiz City LIST OF HONOR STUDENTS SECOND SEMESTER 2016-2017 FIRST HONORS Name Name of High School Course GPA Lowest Grade Total Units Go, Philip Nathaniel T. Misamis Union High School BSCPE5 1.10 1.25 18 Perez, Deanne Ollie N. Lanao Del Norte National Comprehensive High School BEED2 1.16 1.25 27 Lenon, Hazel Coleen M. Immaculate Conception Archdiocesan School BSA2 1.17 1.75 26 Malinis, Aldones T. LSU-Integrated School BSA3 1.17 1.50 21 Pacas, Jan Marco A. Sacred Heart Diocesan School, Inc. BEED2 1.19 1.50 27 Abellana, Regean M Ozamiz City National High School BSBA2 1.21 1.25 20 Apilan, Jenclarice O. Misamis Occidental National High School BSED2 1.21 1.50 24 Edma, Jojie B. Labo National High School ABPOLSC2 1.21 1.50 20 Quilab, Mary Honey T. LSU-Integrated School BSED3 1.21 1.50 18 Cejudo, Vie B. Molave Vocational Technical School BSED2 1.24 1.50 27 Ostia, Deter B. Sacred Heart Diocesan School, Inc. BSED2 1.28 1.75 24 Ponce, Marillac P. Talairon National High School BSA4 1.28 1.75 19 Dioquino, Dennis Mitchel L. Ozamiz City National High School BSBA2 1.31 1.50 23 SECOND HONORS Name Name of High School Course GPA Lowest Grade Total Units Cerafica, Rhizzia May A. Tudela National Comprehensive High School BSED2 1.31 1.75 24 Baldicantos, Jessa N. Holy Family High School Of Ramon Magsaysay, Inc. BSTM2 1.32 1.50 20 Fuentes, Blessy Dailuh M. -

List of Pamb Members Enbanc

LIST OF PAMB MEMBERS ENBANC NAME AND DESIGNATION NAME OF AGENCY LGU's/NGO's/OGA's 1. DR. CORAZON B. GALINATO, CESO, IV Regional Executive Director PAMB Chairman DENR BELEN O. DABA Regional Technical Director for PAWCZMS 2. HON. JUANIDY M. VIÑA Municipal Mayor LGU CONCEPCION 3. HON. DONJIE D. ANIMAS Municipal Mayor LGU SAPANG DALAGA 4. HON. SVETLANA P. JALOSJOS Municipal Mayor LGU BALIANGAO 5. HON. LUISITO B. VILLANUEVA, JR. Municipal Mayor LGU CALAMBA 6. HON AGNES V. VILLANUEVA Municipal Mayor LGU PLARIDEL 7. HON. MARTIN C. MIGRIÑO Municipal Mayor LGU LOPEZ JAENA 8. HON. JASON P. ALMONTE City Mayor CITY OF OROQUIETA 9. HON. JIMMY R. REGALADO Municipal Mayor LGU ALORAN 10. HON. MERIAM L. PAYLAGA Municipal Mayor LGU PANAON 11. HON. RANULFO B. LIMQUIMBO Municipal Mayor LGU JIMENEZ 12. HON. DELLO T. LOOD Municipal Mayor LGU SINACABAN 13. HON. ESTELA R. OBUT-ESTAÑO Municipal Mayor LGU TUDELA 14. HON. DAVID M. NAVARRO Municipal Mayor LGU CLARIN 15. HON. NOVA PRINCESS P. ECHAVEZ City Mayor CITY OF OZAMIZ 16. HON. PHILIP T. TAN City Mayor CITY OF TANGUB 17. HON. SAMSON R. DUMANJUG Municipal Mayor LGU BONIFACIO 18. HON. RODOLFO D. LUNA Municipal Mayor LGU DON VICTORIANO 19. HON. DARIO S. LAPORE Brgy. Gandawan, Barangay Captain Don Victoriano 20. HON. EMELIO C. MEDEL Brgy. Mara-mara, Don Barangay Captain Victoriano 21 HON. JOMAR ENDING Brgy. Lake Duminagat, Don Barangay Captain Victoriano 22. HON. ROMEO M. MALOLOY-ON Brgy. Lalud, Don Victoriano Barangay Captain 23. HON. ROGER D. ACA-AC Brgy. Liboron, Don Victoriano Barangay Captain 24. HON. -

Mi:.T.~S Secretary to the Sanggunian ATTESTED: I~~{(, AURO VIRGINIAM.ALMONTE / Vice-Governor/Presiding Officer () {Of:Z.G (Ill Rs.436.Moa80klgus

Republic of the Philippines PROVINCE OF MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL Office oftlie Sa11f}Dunia11f} CJ>anfafa:wioan Capitol, Oroquieta City Excerpts from the MINUTES ofthe SPECIAL SESSION ofthe Sangguniang Panlalawigan ofMisamis Occidental held at the Sangguniang Panlalawigan Session Hall, Misamis Occidental Provincial Capitol Building, Oroquieta City on October 20, 2016. HON. AURORA VIRGINIA M. ALMONTE - P Vice-Governor/Presiding Officer HON. MENA A. LUANSING OB HON. RICHARD T. CENTINO - P HON. PABLO STEPHEN C. TY P Board Member Board Member Board Member HON. ZALDY G. DAMINAR - P HON. DAN M. NAVARR~ P HON. GERARD HlLARION M. RAMIRO-P Board Member Board Member Board Member/(FABC-Pres.) HON. EMETERIO B. ROA, SR. - OB HON.ROYM. YAP-P HON. RICARDO O. PAROJINOG- OB BM/Asst. Majority Floor Leader Board Member Board Member (PCL) HON. OCTAVIO O. PAROJINOG, JR - P HON. TITO B. DECINA-P HON. DODGE L. CABAHUG, SR. -P Board Member BM/Minority Floor Leader Board Member/IP Representative HON. LEL M. BLANCO- P BM/MaJority Floor Leader Legend: P -Present OL On Leave OB- Official BUSiness OT-Official Trip RESOLUTION NO. 436-16 A RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING mE HONORABLE PROVINCIAL GOVERNOR HERMINIA M. RAMIRO, IN BEHALF OF mE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT OF MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL, TO ENTER INTO A MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT (MOA) WITH mE LOCAL CIDEF EXECUTIVES OF mE MUNICIPALITIES OF TUDELA- HON. SAMUEL L. PAROJINOG, SINACABAN- HON. CRISINCIANO E. MAHILAC, JIMENEZ HON. ROSARIO K. BALAIS, LOPEZ JAENA- HON. MICHAEL P. GUTIERREZ, BALIANGAO- HON. AGNE V. YAP, SR., CITY OF OROQUIETA- HON. JASON P. ALMONTE, RELATIVE TO' THE ALLOCATION OF EIGHTY THOUSAND (p80,OOO.OO) PESOS FROM THE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT TO mE CONCERNED LGUs FOR mEIR VARIUOS PROJECTS IN RELATION TO THE CELEBRATION OF mE 87TH PROVINCIAL ANNIVERSARY AND 7TH PASUNGKO S'G MIS OCC FESTIVAL WHEREAS, the 87 th Provincial Anniversary and the 7th Pasungko S'g Misamis Occidental Festival is an annual celebration of thanksgiving to be held on November 2-30. -

TACR: Philippines: Road Sector Improvement Project

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 41076-01 February 2011 Republic of the Philippines: Road Sector Improvement Project (Financed by the Japan Special Fund) Volume 1: Executive Summary Prepared by Katahira & Engineers International In association with Schema Konsult, Inc. and DCCD Engineering Corporation For the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, Lao PDR and This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Governments concerned, and ADB and the Governments cannot be held liable for its contents. All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY PORT AREA, MANILA ASSET PRESERVATION COMPONENT UNDER TRANCHE 1, PHASE I ROAD SECTOR INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND INVESTMENT PROGRAM (RSIDIP) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY in association KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS with SCHEMA KONSULT, DCCD ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL INC. CORPORATION Road Sector Institutional Development and Investment Program (RSIDIP): Executive Summary TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT ................................................... ES-1 2. OBJECTIVES OF THE PPTA............................................................ ES-1 3. SCOPE OF THE STUDY ................................................................. ES-2 4. SELECTION OF ROAD SECTIONS FOR DESIGN IN TRANCHE 1 ....... ES-3 5. PROJECT DESCRIPTION .............................................................. ES-8 -

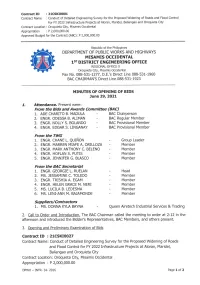

Minutes of Opening of Bids for Contract ID: 21CSKI0001

Contract ID 21CSKI0001 Contract Name : Conduct of Detailed Engineering Survey for the Proposed Widening of Roads and Flood Control For FY 2022 Infrastructure Projects at Aloran, Plaridel, Baliangao and Oroquieta City Contract Location : Oroquieta City, Misamis Occidental Appropriation : P 2,000,000.00 Approved Budget for the Contract (ABC): P 2,000,000.00 Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 1ST DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE REGIONAL OFFICE X Oroquieta City, Misamis Occidental Fax No. 088-531-1277, D.E.'s Direct Line 088-531-1960 BAC CHAIRMAN'S Direct Line 088-531-1923 MINUTES OF OPENING OF BIDS June 29, 2021 1. Attendance. Present were: From the Bids and A wards Committee (BA C) 1. ADE CHARITO B. MADULA - BAG Chairperson 2. ENGR. ODESSA B. ALTMAN - BAC Regular Member 3. ENGR. NOLLY S. BOLANDO - BAC Provisional Member 4. ENGR. EDGAR S. LINGANAY - BAC Provisional Member From the TWG 1. ENGR. CHANE L. QUINON - Group Leader 2. ENGR. MARREN MIAFE A. ORILLOZA - Member 3. ENGR. MARK ANTHONY C. BELENO - Member 4. ENGR. HOFLAN S. PUTIS - Member 5. ENGR. JENNIFER G. BLASCO - Member From the BA C Secretariat 1. ENGR. GEORGIE L. RUELAN - Head 2. MS. JESSAMINE C. TOLEDO - Member 3. ENGR. TRISHIA A. EGAM - Member 4. ENGR. HELEN GRACE M. NERI - Member 5. MS. LUCILA B. LEDESMA - Member 6. MS. LENT-ANN M. BAJAMONDE - Member Suppliers/Contractors 1. MS. DONNA KYLA BAYNA Queen Airetech Industrial Services & Trading 2. Call to Order and Introduction. The BAC Chairman called the meeting to order at 2:12 in the afternoon and introduced the Bidder's Representatives, BAC Members, and others present. -

Report for World Migratory Bird Day 2021 Event in East Asian-Australasian Flyway

EAAFP WMBD2021Small Grant Application Form Report for World Migratory Bird Day 2021 Event in East Asian-Australasian Flyway 1 EAAFP WMBD2021Small Grant Application Form Date of Submission: May 20, 2021 1. EVENT INFORMATION 1.1 Contact Information Full Name EnP. Grace V. Villanueva Name of the organisation Misamis University,Philippines Name(s) of the division Misamis University Community Extension Program and/or position / Director Misamis University College of Maritime Education Type of the organisation - Academe Government/NGO/Private Sector/Other Email [email protected] Postal address H.T. Feliciano Street, Aguada, Ozamiz City, Philippines Office phone numbers 088-531 loc 135 (Your) Cell number (optional) 09163514058 Fax(optional) 521-0431 Fax 2917 Website(optional) https:www.mu.edu.ph Additional contact person For. Bobby B. Alaman (optional) Date of submission May 18, 2021 1.2 Event tile: Conservation of Wildlife Migratory Bird and Wetland Areas in Misamis Occidental, Philippines through Advocacy and Capacity Development 1.3 Event Location - Where did your event take place? Name of country Philippines Name of city Ozamiz City Name of event place/venue Installation of CEPA Billboards- Barangay Migpange, Bonifacio, Misamis Occidental, Barangay Mantic, Tangub City and Poblacion, Sinacaban, Misamis Occidental, Municipalities of Plaridel and Baliangao Posting of CEPA Posters- 25 coastal barangays within Misamis Occidental. Virtual Lecture –Workshop hosted by Misamis University held at MUCEP Office, Misamis University, Ozamiz City via Zoom Celebration of WMBD 2021 Coastal Clean Up and Bird Watching – Barangay Mialen, Clarin, Misamis Occidental 2 EAAFP WMBD2021Small Grant Application Form 1.4 Event Type - Check the relevant categories of your event type Public awareness activity – local and/or national / Field Trip (e.g. -

The Case of Iligan City Leilanie Basilio and Jeremiah Cabasan DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Local Governance and the Challenges of Economic Distress: The Case of Iligan City Leilanie Basilio and Jeremiah Cabasan DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2004-45 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. December 2004 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 3rd Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: 8924059 and 8935705; Fax No: 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph Local Governance and the Challenges of Economic Distress: The Case of Iligan City With Special Focus on the Impact of the Closure of the National Steel Corporation By Leilanie Basilio and Jeremiah Cabasan* November 2004 Abstract Trends in economic development influence population outcomes in an area. Increasing economic opportunities that are typically linked to industrialization enhance the attractiveness of a location and result to population increases. The inverse of this process could also be true, that is, an economic distress could hit an area and force its residents to leave and seek better forts. -

OCHA-PHL-Mindanao Displacement 14June2017

Philippines: Mindanao Displacement Snapshot (14 June 2017) MARAWI ARMED CONFLICT Total number of displaced population for the Marawi As of 14 June, over 320,000 people are now armed conflict is derived from daily DSWD DROMIC from displaced as a result of the armed conflict in Marawi different regions. ! City, Lanao del Sur that started on 23 May 2017. Total displacement figures for Iligan is taken from Iligan CSWD report, for Lanao del Norte (excluding Iligan) and 93 per cent are staying with host families, while Misamis Oriental Misamis Oriental is taken from Region 10 DSWD DROMIC 21,800 (7%) people are staying in 79 evacuation ! Cagayan de Oro and for Lanao del Sur, the ARMM Iligan operation center centres. ! DROMIC report is used. Taking figures from different sources is an attempt to Iligan Bay ! ! better capture total number of displaced population taking 320,000 into consideration that the different DSWD offices capture data in their area of operation. People Displaced Iligan! City Agusan del Sur 298,200 in host families Misamis ! ! ! ! ! Occidental ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lanao del Norte ! Marawi City ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Zamboanga del Sur ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lake ! ! Lanao! 21,800 inside evacuation centres ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bukidnon ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MAGUINDANAO ARMED CONFLICT Lanao del Sur ! ! On 4 June, armed conflict between military and ! Davao del Norte non-state armed actors resulted in the displacement of 36,000 people from six municipalities in ! Maguindanao. 36,000 Celebes Sea People Displaced Cotabato Cotabato City Davao del Sur Davao City MAGUINDANAO FLOODING The province of Maguindanao has experienced rains and local thunderstorms since May 2017 that caused Areas affected by flooding ! rivers to overflow which resulted to flooding in 21 ! ! municipalities. -

DEPARTMENT of PUBLIC WORKS and HIGHWAYS MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 2Nd District Engineering Office

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 2nd District Engineering Office Department of Public Works and Highways-MODEO 2, Tangub City As of December 2017 Code (PAP) Procurement Program/Project PMO/ End-User Mode of Actual Procurement Activity Source of Funds ABC (PhP) Contract Cost (PhP) List of Invited Observers Date of Receipt of Invitation Remarks Procurement (Explaining Pre-Proc Conference Ads/Post of IAEB Pre-bid Conf Eligibility Check Sub/Open of Bids Bid Evaluation Post Qual Notice of Award Contract Signing Notice to Proceed Delivery/ Completion Acceptance/ Pre-Proc Pre-bid Eligibility Sub/Ope Bid Post Qual changes from the Turnover Conf Conf Check n of Bids Evaluation APP) COMPLETED PROCUREMENT ACTIVITIES 1 16KJ0118 Construction of Multi-Purpose Building 8-Dec-16 December 9-16, 2016 16-Dec-16 09-May-17 09-May-17 16-May-17 17-May-17 13-Jul-17 28-Jul-17 31-Jul-17 5,940,000.00 5,642,906.01 COA - Jaime L. Canedo at Brgy. Guba, Clarin, Misamis Construction Section Public Bidding GAA CY 2017 7-Dec-16 25-Apr-17 25-Apr-17 Occidental PICPA- Invited but failed to attend PICE - Invited but failed to attend 2 16KJ0124 Construction and Maintenance of 08-Dec-16 December 9-16, 2016 16-Dec-16 29-Dec-16 29-Dec-16 03-Jan-17 12-Jan-17 4,214,000.00 4,118,185.77 05-Jul-17 20-Jul-17 24-Jul-17 COA - Invited but failed to attend Bridges along National Roads (Rehabilitation/Major Repair of PICPA- Invited but failed to attend Permanent Bridge) – Cluster XII, PICE - Invited but failed to attend Clarin Br.