Isabela Alcogas Corporation's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

NDRRMC Update Sitrep 5 Fire in Butuan City

II. CASUALTIES AGE/ NAME ADDRESS GENDER DEAD (17) 1. Rogelyn Mantubacan F Butuan City 2. Jonalie Amor F Valencia, Bukidnon 3. Judelyn Ore F Dipolog 4. Villa Rose Dumagpi F Iligan City 5. Ellenie Ocoy F Malaybalay City 6. Prences Grace Sayre F Ozamiz City 7. Anniejoy Lagura F Cagayan de Oro City 8. Mylyn Lirazon F Zamboanga City 9. Pengky Despolo F Tandag, Surigao del Sur 10. Jessie Dayuja F Valencia City 11. Princess Mae Figueras F Tandag, Surigao del Sur 12. Irene Baliquig F Zamboanga del Sur 13. Hazel Cabaña F Valencia City 14. Liezel Dalaygon F Oroqueta City 15. Jeba Salbigsal F Iligan City 16. Maribel Buico F Malaybalay City 17. Gladys Hope Sabila F Ozamiz City INJURED/ SURVIVORS (3) 1. Mylene Tolo 25/F Aurora, Zamboanga 2. Grace Canoy 22/F Don Carlos, Bukidnon 3. Vicky Velez 23/F Manga, Tangub The survivors who suffered 3 rd degree burns managed to escape by jumping off the building. They were all brought to the Elisa R. Ochoa Maternity Hospital in Butuan for medical treatment. Initial Names of dead persons were provided by BFP Butuan City Fire Station but is still subject for further confirmation with the official report from PRO-13 SOCO III. DAMAGE TO PROPERTIES • The Novo Store razed other adjacent business establishments namely: SMART Telecom Service Center Western Union St. Peter Life Plan Empress Badminton Center • Estimated Cost of Damage to Properties: 30 Million Pesos (Php 30,000,000.00) IV. ACTIONS TAKEN • In view of the general alarm declared by the BFP Butuan City the following emergency responders proceeded to the fire scene to conduct fire fighting operations: BFP Butuan City; Fire Stations in Ampayan, Buenavista, Cabadbaran, Kitcharao, and Nasipit all in Agusan del Norte; Butuan Search and Rescue Team (BUSART); volunteers of Boy Scout of the Philippines Butuan City Chapter; Butuan City Police Office (BCPO); Scene of the Crime Operatives (SOCO); SWAT Team; Red Cross; and CHO Disaster team. -

Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project

Community Management Plan July 2019 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project SAIA-Higaonon Tribal Council Inc. and Itoy Amosig Higaonon Tribal Community Inc. under Kalanawan Ancestral Domain Prepared by Higaonon community of Malitbog, Bukidnon for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the Asian Development Bank i ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ADSDPP - Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan AGMIHICU - Agtulawon Mintapod Higaonon Cumadon AFP - Armed Forces of the Philippines CADT - Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title CLUP - Community Land Use Plan CMP - Community Management Plan CP - Certificate of Pre-condition DepEd - Department of Education DENR - Department of Environment and Natural Resources DOH - Department of Health DTI - Department of Trade and Industry FGD - Focus Group Discussion FPIC - Free, Prior and Informed Consent GO - Government Organizations GRC - Gender Responsiveness Checklist IAHTCO - Itoy Amosig Higaonon Tribal Community Organization, Inc. ICC - Indigenous Cultural Communities IEC - Information, Education and Communication INREMP - Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project IP - Indigenous Peoples IPDF - Indigenous People’s Development Framework IPMR - Indigenous People Mandatory Representative IPO - Indigenous Peoples Organization IPP - Indigenous Peoples Plan IPRA - Indigenous Peoples Rights Act LGU - Local Government Unit M&E - Monitoring and Evaluation Masl - Meters above sea level MLGU - Municipal Local Government -

Philippines: Marawi Armed-Conflict 3W (As of 18 April 2018)

Philippines: Marawi Armed-Conflict 3W (as of 18 April 2018) CITY OF Misamis Number of Activities by Status, Cluster & Number of Agencies EL SALVADOR Oriental 138 7,082 ALUBIJID Agencies Activities INITAO Number of CAGAYAN DE CLUSTER Ongoing Planned Completed OPOL ORO CITY (Capital) organizations NAAWAN Number of activities by Municipality/City 1-10 11-50 51-100 101-500 501-1,256 P Cash 12 27 69 10 CCCM 0 0 ILIGAN CITY 571 3 Misamis LINAMON Occidental BACOLOD Coord. 1 0 14 3 KAUSWAGAN TAGOLOAN MATUNGAO MAIGO BALOI POONA KOLAMBUGAN PANTAR TAGOLOAN II Bukidnon PIAGAPO Educ. 32 32 236 11 KAPAI Lanao del Norte PANTAO SAGUIARAN TANGCAL RAGAT MUNAI MARAWI MAGSAYSAY DITSAAN- CITY BUBONG PIAGAPO RAMAIN TUBOD FSAL 23 27 571 53 MARANTAO LALA BUADIPOSO- BAROY BUNTONG MADALUM BALINDONG SALVADOR MULONDO MAGUING TUGAYA TARAKA Health 79 20 537 KAPATAGAN 30 MADAMBA BACOLOD- Lanao TAMPARAN KALAWI SAPAD Lake POONA BAYABAO GANASSI PUALAS BINIDAYAN LUMBACA- Logistics 0 0 3 1 NUNUNGAN MASIU LUMBA-BAYABAO SULTAN NAGA DIMAPORO BAYANG UNAYAN PAGAYAWAN LUMBAYANAGUE BUMBARAN TUBARAN Multi- CALANOGAS LUMBATAN cluster 7 1 146 32 SULTAN PICONG (SULTAN GUMANDER) BUTIG DUMALONDONG WAO MAROGONG Non-Food Items 1 0 221 MALABANG 36 BALABAGAN Nutrition 82 209 519 15 KAPATAGAN Protection 61 37 1,538 37 Maguindanao Shelter 4 4 99 North Cotabato 7 WASH 177 45 1,510 32 COTABATO CITY TOTAL 640 402 6,034 The boundaries, names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Creation date: 18 April 2018 Sources: PSA -

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018 Head Office Project Contractor Amount of Project Date of NOA Date of Contract Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 27-Nov-19 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of JARZOE Builders, Inc./ DALEBO Construction and General. 328,013,357.76 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Estancia, Iloilo; Culasi, Roxas City; and Dumaguit, New Washington, Aklan Merchandise/JV Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of Lipata, Goldridge Construction & Development Corporation / JARZOE 200,000,842.41 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Culasi, Antique; San Jose de Buenavista, Antique and Sibunag, Guimaras Builders, Inc/JV Consultancy Services for the Conduct of Feasibility Studies and Formulation of Master Plans at Science & Vision for Technology, Inc./ Syconsult, INC./JV 26,046,800.00 12-Nov-19 16-Dec-19 Selected Ports Davila Port Development Project, Port of Davila, Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte RCE Global Construction, Inc. 103,511,759.47 24-Oct-19 09-Dec-19 Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Rehabilitation of Existing RC Pier, Port of Baybay, Leyte A. -

REGION 10 #Coopagainstcovid19

COOPERATIVES ALL OVER THE COUNTRY GOING THE EXTRA MILE TO SERVE THEIR MEMBERS AND COMMUNITIES AMIDST COVID-19 PANDEMIC: REPORTS FROM REGION 10 #CoopAgainstCOVID19 Region 10 Cooperatives Countervail COVID-19 Challenge CAGAYAN DE ORO CITY - The challenge of facing life with CoViD-19 continues. But this emergency revealed one thing: the power of cooperation exhibited by cooperatives proved equal if not stronger than the CoVID-19 virus. Cooperatives continued to show their compassion not just to ease the burden of fear of contracting the deadly and unseen virus, but also to ease the burden of hunger and thirst, and the burden of poverty and lack of daily sustenance. In Lanao del Norte, cooperatives continued to show their support by giving a second round of assistance through the Iligan City Cooperative Development Council (ICCDC), where they distributed food packs and relief goods to micro cooperatives namely: Lambaguhon Barinaut MPC of Brgy. San Roque, BS Modla MPC, and Women Survivors Marketing Cooperative. All of these cooperatives are from Iligan City. In the Province of Misamis Oriental, the spirit of cooperativism continues to shine through amidst this pandemic. The Fresh Fruit Homemakers Consumer Cooperative in Mahayahay, Medina, Misamis Oriental extended help by distributing relief food packages to their members and community. The First Jasaan Multi-Purpose Cooperative provided food assistance and distributed grocery items to different families affected by Covid 19 in Solana, Jasaan, Misamis Oriental. Meanwhile, the Misamis Oriental PNP Employees Multi- Purpose Cooperative initiated a gift-giving program to the poor families of San Martin, Villanueva, Misamis Oriental. Finally, the Mambajao Central School Teachers and Employees Cooperative (MACESTECO) in Mambajao, Camiguin distributed rice packs and relief items to their community. -

The Impact of Remittances on Human Resource Development Decisions, Youth Employment Decisions, and Entrepreneurship in the Philippines Using CBMS Data

The impact of remittances on human resource development decisions, youth employment decisions, and entrepreneurship in the Philippines using CBMS Data Christopher James R. Cabuay Angelo King Institute for Economic and Business Studies De La Salle University I. Introduction a. Background For the past few decades, international migration has been an avenue for Filipinos to seek employment abroad. The stock of Filipino migrants has reached 10,489,628 in 2012 (Commission of Filipinos Overseas [CFO], 2014). Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) have been going to Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Qatar for employment (Philippine Overseas Employment Administration [POEA], 2014). Migration is often coupled with the sending of remittances to one’s household in the country of origin. These remittances have become a major avenue for many households to maximize income and smoothen consumption spending over time. OFW remittances has been a significant driver of the Philippine economy especially since it fuels the property market with a strong demand from medium-low-income wage earners among families with OFWs (Villegas, 2014). Remittances have grown over the past decades and have reached 18.76 USD billion in 2010 (BangkoSentralngPilipinas [BSP], 2014) and growing further to 22.97 USD billion in 2013. The largest remittances come from USA (about 9.9 USD billion), followed by Saudi Arabia (approximately 2.1 USD billion), United Kingdom (1.32 USD billion) United Arab Emirates (1.26 USD billion), Singapore, Japan, and Canada (BSP, 2014). This indicates the dependency of the Philippine economy to the remittances from overseas workers. Despite the prevalence of the phenomenon, a significant question still remains: how are remittances being used by families? Tabuga (2007) finds that remittances generally decrease the household’s budget allocated for food, but increases the budget allocated for education, medical care, housing and repairs, consumer goods, leisure, gifts, and durables. -

Volume Xxiii

ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME XXIII NEW YORK PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES 1925 Editor CLARK WISSLER FOREWORD Louis ROBERT SULLIVAN Since this volume is largely the work of the late Louis Robert Sulli- van, a biographical sketch of this able anthropologist, will seem a fitting foreword. Louis Robert Sullivan was born at Houlton, Maine, May 21, 1892. He was educated in the public schools of Houlton and was graduated from Bates College, Lewiston, Maine, in 1914. During the following academic year he taught in a high school and on November 24, 1915, he married Bessie Pearl Pathers of Lewiston, Maine. He entered Brown University as a graduate student and was assistant in zoology under Professor H. E. Walters, and in 1916 received the degree of master of arts. From Brown University Mr. Sullivan came to the American Mu- seum of Natural History, as assistant in physical anthropology, and during the first years of his connection with the Museum he laid the foundations for his future work in human biology, by training in general anatomy with Doctor William K. Gregory and Professor George S. Huntington and in general anthropology with Professor Franz Boas. From the very beginning, he showed an aptitude for research and he had not been long at the Museum ere he had published several important papers. These activities were interrupted by our entrance into the World War. Mr. Sullivan was appointed a First Lieutenant in the Section of Anthropology, Surgeon-General's Office in 1918, and while on duty at headquarters asisted in the compilation of the reports on Defects found in Drafted Men and Army Anthropology. -

Report for World Migratory Bird Day 2021 Event in East Asian-Australasian Flyway

EAAFP WMBD2021Small Grant Application Form Report for World Migratory Bird Day 2021 Event in East Asian-Australasian Flyway 1 EAAFP WMBD 2021 Small Grant Application Form Date of Submission: May 20, 2021 1. EVENT INFORMATION 1.1 Contact Information Full Name EnP. Grace V. Villanueva Name of the organisation Misamis University,Philippines Name(s) of the division Misamis University Community Extension Program and/or position / Director Misamis University College of Maritime Education Type of the organisation - Academe Government/NGO/Private Sector/Other Email [email protected] Postal address H.T. Feliciano Street, Aguada, Ozamiz City, Philippines Office phone numbers 088-531 loc 135 (Your) Cell number (optional) 09163514058 Fax(optional) 521-0431 Fax 2917 Website(optional) https:www.mu.edu.ph Additional contact person For. Bobby B. Alaman (optional) Date of submission May 18, 2021 1.2 Event tile: Conservation of Wildlife Migratory Bird and Wetland Areas in Misamis Occidental, Philippines through Advocacy and Capacity Development 1.3 Event Location - Where did your event take place? Name of country Philippines Name of city Ozamiz City Name of event place/venue Installation of CEPA Billboards- Barangay Migpange, Bonifacio, Misamis Occidental, Barangay Mantic, Tangub City and Poblacion, Sinacaban, Misamis Occidental, Municipalities of Plaridel and Baliangao Posting of CEPA Posters- 25 coastal barangays within Misamis Occidental. Virtual Lecture –Workshop hosted by Misamis University held at MUCEP Office, Misamis University, Ozamiz City via Zoom Celebration of WMBD 2021 Coastal Clean Up and Bird Watching – Barangay Mialen, Clarin, Misamis Occidental 2 EAAFP WMBD 2021 Small Grant Application Form 1.4 Event Type - Check the relevant categories of your event type Public awareness activity – local and/or national / Field Trip (e.g. -

Impacts of Management Intervention on the Aquatic Habitats of Panguil Bay, Philippines ABSTRACT

Journal of Environment and Aquatic Resources. 1(1): 1-14 (2009) Impacts of Management Intervention on the Aquatic Habitats of Panguil Bay, Philippines Proserpina G. Roxas, Renoir A. Abrea and Wilfredo H. Uy Mindanao State University at Naawan, 9023 Naawan, Misamis Oriental, Philippines [email protected] ABSTRACT Impacts of previous interventions on the coastal habitats in Panguil Bay, Philippines were determined by assessing the bay’s mangroves, seaweed and seagrass communities, coral reefs, marine sanctuaries, and artificial reefs using standard and modified methods. The bay has 21 true mangrove and 15 mangrove-associated species that serve as habitat for commercially important fish and crustaceans, particularly the mud crab, Scylla spp. Mangrove resources, however, are continuously threatened by fishpond development and other uses resulting in a significant decline in cover to only 4.36% of the estimated cover in 1950. The seaweed community is comprised of 26 species of green algae, 18 brown algae, 24 red algae, and 4 blue green algae. The present number is lower compared to the 105 species recorded in 1991. Most seagrasses and seaweeds are found only near the bay’s mouth, while only few species represented by Enhalus acoroides, Enteromorpha and Neomeris are found in the inner part of the bay. The average cover of seaweeds and seagrass decreases from the mouth towards the inner side of the bay. There is a significant reduction in the cover since 1991 except for the seaweeds in Maigo, Lanao del Norte and the seagrasses in Clarin, Misamis Occidental. In several stations, seagrass cover is already less than 20% of that reported in 1991. -

NORTHERN MINDANAO Directory of Mines and Quarries

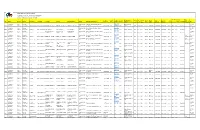

MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU REGIONAL OFFICE NO.: X- NORTHERN MINDANAO Directory of Mines and Quarries - CY 2020 Other Plant Locations Status Mine Site Mine Mine Site E- Head Office Head Office Head Office E- Head Office Mine Site Mailing Type of Permit Date Date of Area municipality, Non- Telephon Site Fax mail barangay Year Region Mineral Province Municipality Commodity Contractor Operator Managing Official Position Head Office Mailing Address Telephone No. Fax No. mail Address Website (hectares) province Producing TIN Address e No. No. Address Permit Number Approved Expiration Producing donjieanim 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man Poblacion, Sapang Dalaga, Misamis as@yahoo Dioyo, Sapang 191-223- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Sapang Dalaga Sand and Gravel ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ager Occidental 9654955493 N/A .com N/A Dalaga N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-07-19 11/10/2019 10/10/2020 1.00 N/A N/A Producing 205 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man South Western, Calamba, Misamis ljcyap7@g 432-503- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Calamba Sand and Gravel YAP, LORNA T. YAP, LORNA T. YAP, LORNA T. ager Occidental 9466875752 N/A mail.com N/A Sulipat, Calamba N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-18-19 04/02/2020 03/02/2021 1.9524 N/A N/A Producing 363 maconsuel 10-Northern Non- Misamis ROGELIO, MARIA ROGELIO, MA. ROGELIO, MA. Proprietor/Man Northern Poblacion, Calamba, Misamis orogelio@ 325-550- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Calamba Sand and Gravel CONSUELO A. CONSUELO A. CONSUELO ager Occidental 9464997271 N/A gmail.com N/A Solinog, Calamba N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-03-20 24/06/2020 23/06/2021 1.094 N/A N/A Producing 921 noel_pagu 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man Southern Poblacion, Plaridel, Misamis e@yahoo. -

Ozamis (City) Panaon Plaridel Sapang Dalag

Item Indicators Aloran Baliangao Bonifacio Clarin Jimenez Lopez Jaena Orquieta (city) Ozamis (city) Panaon Plaridel Sapang Dalaga Sinacaban Tangub (city) Tudela 1.1 M/C Fisheries Ordinance Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.2 Ordinance on MCS No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes No No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.3a Allow Entry of CFV No No No No No No No No No No report submitted N/A No N/A No 1.3b Existence of Ordinance N/A No No Yes No No report submitted No N/A N/A N/A 1.4a CRM Plan Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.4b ICM Plan Yes Yes Yes No Yes No No No No report submitted Yes Yes Yes 1.4c CWUP Yes No No No No No No report submitted Yes No Yes 1.5 Water Delineation Yes Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.6a Registration of fisherfolk Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.6b List of org/coop/NGOs Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7a Registration of Boats Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7b Licensing of Boats Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.7c Fees for Use of Boats No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.8a Licensing of Gears Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.8b Fees for Use of Gears No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No report submitted Yes Yes Yes No 1.9a Auxiliary Invoices No Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes No No report