Draft Closed Basin Subbasin Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water-Quality Assessment of the Upper Snake River Basin, Idaho and Western Wyoming Summary of Aquatic Biological Data for Surface Water Through 1992

WATER-QUALITY ASSESSMENT OF THE UPPER SNAKE RIVER BASIN, IDAHO AND WESTERN WYOMING SUMMARY OF AQUATIC BIOLOGICAL DATA FOR SURFACE WATER THROUGH 1992 By TERRY R.MARET U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 95-4006 Boise, Idaho 1995 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bruce Babbitt, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center 230 Collins Road Open-File Reports Section Boise, ID 83702-4520 Box 25286, MS 517 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 FOREWORD The mission of the U.S. Geological Survey Describe how water quality is changing over time. (USGS) is to assess the quantity and quality of the Improve understanding of the primary natural and earth resources of the Nation and to provide informa human factors that affect water-quality conditions. tion that will assist resource managers and policymak- This information will help support the develop ers at Federal, State, and local levels in making sound ment and evaluation of management, regulatory, and decisions. Assessment of water-quality conditions and monitoring decisions by other Federal, State, and local trends is an important part of this overall mission. agencies to protect, use, and enhance water resources. One of the greatest challenges faced by water- The goals of the NAWQA Program are being resources scientists is acquiring reliable information achieved through ongoing and proposed investigations that will guide the use and protection of the Nation's of 60 of the Nation's most important river basins and water resources. -

Eology of the Southern Part )F the Lemhi Range, Idaho

:;eology of the Southern Part )f the Lemhi Range, Idaho 'y CLYDE P. ROSS :oNTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY ~EOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1081-F NITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1961 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washin!1ton 25, D.C. CONTENTS Page Abstract--------------------------------------------------------- 189 Introduction------------------------------------------------------ 189 Location and scope of the report________________________________ 189 Acknowledgments--------------------------------------------- 191 TopographY------------------------------------------------------ 192 LemhiRange_________________________________________________ 192 Valley of Birch Creek__________________________________________ 193 Valley of Little Lost River_ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 193 Stratigraphy and petrography __________________________ ------------_ 194 Generalfeatures----------------------------------------------- 194 Precambrianrocks--------------------------------------------- 195 Swauger quartzite_ _ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 195 Lower Paleozoic rocks ___ -------________________________________ 201 Kinnikinic quartzite_ _ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 201 Saturday Mountain formation and overlying dolomite__________ 203 Three Forks limestone -

Longitudinal and Seasonal Distribution of Benthic Invertebrates in the Little Lost River, Ldaho

Longitudinal and Seasonal Distribution of Benthic Invertebrates in the Little Lost River, ldaho DOUGLAS A. ANDREWS and G. WAYNE MINSHALL Department of Biology, Idaho State University, Pocatello 03209 ABSTRACT:A yearlong investigation of the Little Lost River, ldaho (five sites) was conducted to determine the environmental conditions and benthic invertebrate com- munity composition of the stream and to discover factors responsible for distribution of the benthos. All chemical constituents measured showed a tendency to increase from headwaters to mouth. Stream temperatures ranged from 0-15 C near the headwaters and 0 to 22 C near the mouth. Chlorophyll a content of the periphyton was low (1- 19 mg/m2) following heavy winter ice cover and spring runoff, but attained relatively high levels (12-68 mg/m2) by the end of September. Allochthonous detritus levels were highest (64-96 g/m2) near the headwaters; the lowest levels (16-24 g/m2) were found in areas where the riparian vegetation was restricted largely to sagebrush and grass. The study revealed a fauna comparable in richness to other Rocky Mountain streams. Sixty-two of the 68 taxa collected were insects. Ephemeroptera was the predominant group in terms of both species (29% of total) and number (62% of total). The most common species were Rhithrogenn robusta, R. hageni and Baetis tricaudatus (Ephemeroptera) ; Nemoura sp., Alloperla sp. and Isoperla fulua (Plecoptera) ; and Glossosoma sp. and Hydropsyche sp. (Trichoptera). Mean number of invertebrates was between 1500 and 5000/m2 at the various sites. Local environmental conditions exerted a strong influence on the structure of the invertebrate community at the various locations in the river. -

Distribution of Benthic Invertebrates in the Lost Streams of Idaho

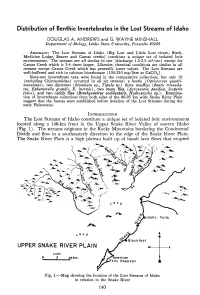

Distribution of Benthic Invertebrates in the Lost Streams of Idaho DOiUGLAS A. ANDREWS and G. WAYNE MINSHALL Department of Biology, Idaho State University, Pocatello 83209 ABSTRACT:The Lost Streams of Idaho (Big Lost and Little Lost rivers; Birch, Medicine Lodge, Beaver and Camas creeks) constitute a unique set of isolated lotic environments. The streams are all similar in size (discharge 1.5-2.5 m3/sec) except for Camas Creek which is 3-4 times larger. Likewise, chemical conditions are similar in all streams except Camas Creek which has generally lower values. The Lost Streams are well-buffered and rich in calcium bicarbonate (100-250 mg/liter as CaCO,). Sixty-one invertebrate taxa were found in the comparative collections, but only 10 (excluding Chironomidae) occurred in all six streams: a beetle (Optioservus quadri- maculatus), two dipterans (Simulium sp., Tipula sp.) three mayflies (Baetis tricauda- tus, Ephemerella grandis, E. inermis), two stone flies (Acroneuria pacifica, Isoperla fulva), and two caddis flies (Brachycentrus occidentalis, Hydropsyche sp.) . Examina- tion of invertebrate collections from both sides of the 80-95 km wide Snake River Plain suggest that the faunas were established before isolation of the Lost Streams during the early Pleistocene. INTRODUCTION The Lost Streams of Idaho constitute a unique set of isolated lotic environments located along a 146-km front in the Upper Snake River Valley of eastern Idaho (Fig. 1). The streams originate in the Rocky Mountains bordering the Continental Divide and flow in a southeasterly direction to the edge of the Snake River Plain. The Snake River Plain is a high plateau built up of basalt lava flows that erupted Fig. -

IDAHO DEPARTMENT of FISH and GAME FISHERY MANAGEMENT ANNUAL REPORT Cal Groen, Director

IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME FISHERY MANAGEMENT ANNUAL REPORT Cal Groen, Director UPPER SNAKE REGION 2009 Brett High Regional Fisheries Biologist Greg Schoby Regional Fisheries Biologist Damon Keen Regional Fisheries Biologist Dan Garren Regional Fisheries Manager March 2011 IDFG 11-107 1 2009 Upper Snake Region Annual Fishery Management Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Lakes and Reservoirs Investigations HENRYS LAKE ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................ 1 METHODS ................................................................................................................................. 2 Population Monitoring ............................................................................................................. 2 Creel Survey ........................................................................................................................... 3 Water Quality .......................................................................................................................... 4 Spawning Operation ............................................................................................................... 4 Riparian Fencing and Fish Screening ..................................................................................... 4 RESULTS .................................................................................................................................. 5 Population Monitoring ............................................................................................................ -

Little Lost River Subbasin TMDL

Little Lost River Subbasin TMDL August 2000 An Allocation of Nonpoint Source Pollutants in the Water Quality Limited Watersheds of the Little Lost River Valley Idaho Department of Environmental Quality 1410 North Hilton Boise, ID 83706 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................1 1.0 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................3 Total Maximum Daily Load ........................................................................................3 History .........................................................................................................................4 Issues of Concern.........................................................................................................5 2.0 WATERSHED ASSESSMENT ..................................................................................6 2.1 WATERSHED DESCRIPTION..........................................................................6 Climate................................................................................................................6 Hydrology ...........................................................................................................6 Geology...............................................................................................................8 Soils ....................................................................................................................8 Geomorphic -

National Wildlife Refuge

Hydrogeomorphic Evaluation of Ecosystem Restoration and Management Options for CAMAS National Wildlife Refuge Prepared For: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 1 Hamer, Idaho Greenbrier Wetland Services Report 14-04 Adonia R. Henry Mickey E. Heitmeyer March 2014 HYDROGEOMORPHIC EVALUATION OF ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT OPTIONS FOR CAMAS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Prepared For: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 1 Camas National Wildlife Refuge Hamer, Idaho By: Adonia R. Henry Scaup & Willet LLC 70 Grays Lake Rd. Wayan, ID 83285 and Mickey E. Heitmeyer Greenbrier Wetland Services Rt. 2, Box 2735 Advance, MO 63730 March 2014 Greenbrier Wetland Services Report No. 14-04 Mickey E. Heitmeyer, PhD Greenbrier Wetland Services Route 2, Box 2735 Advance, MO 63730 www.GreenbrierWetland.com Publication No. 14-04 Suggested citation: Henry, A. R., and M. E. Heitmeyer. 2014. Hy- drogeomorphic evaluation of ecosystem restora- tion and management options for Camas National Wildlife Refuge. Prepared for U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 1, Camas NWR, Hamer, ID. Greenbrier Wetland Services Report 14-04, Blue Heron Conservation Design and Printing LLC, Bloomfield, MO. Photo credits: COVER: Adonia Henry Adonia Henry; Andy Vernon; Cary Aloia, www.Gardners- Gallery.com; Karen Kyle This publication printed on recycled paper by ii Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... -

Methods for Evaluating

Uniled States Department of Agriculture Methods For Evaluating Forest Service Intermountain Stream, Riparian, and Forest and Range Experiment Station Ogden, UT 84401 Biotic Conditions General Technical Report INT-138 May 1983 William S. Platts Walter F. Megahan G. Wayne Minshall THE AUTHORS RESEARCH SUMMARY WILLIAM S. PLATTS is a Research Fishery Biologist for Most stream habitat evaluation techniques currently in the Intermountain Station at Boise, Idaho. He received a use today have not been tested to determine their validity in B.S. degree in conservation-education in 1955 from Idaho describing conditions and have been designed to optimize State University, a M.S. degree in fisheries in 1957, and a time rather than accuracy. The purpose of this report is to Ph.D. degree in fisheries in 1972 from Utah State University. further standardize the way physical and biological attributes From 1957 through 1966, he worked as a Regional Fishery are measured and quantified and to shed light on the Biologist and Supervisor in Enforcement with the Idaho Fish strengths and weaknesses of those attributes. This report and Game Department. From 1966 through 1976, he was discusses some of the environmental parameters that best the Idaho Zone Fishery Biologist for the USDA Forest Serv measure and describe conditions existing in aquatic ice, Intermountain Region and consultant to the Surface ecosystems. The precision and an estimation of the accu Environment and Mining (SEAM) program. He has been in racy that can be expected when measuring many of these his present position since 1976. conditions are given. WALTER F. MEGAHAN is a Principal Research Hydrologist and Leader of the Intermountain Station's Nonpoint Source Pollution Research Work Unit in Boise, Idaho. -

The History and Status of Fishes in the Little Lost River Drainage, Idaho

The History and Status of Fishes in the Little Lost River Drainage, Idaho Bart L. Gamett May 1999 Lost River Ranger District Upper Snake Region Idaho Falls District Salmon-Challis National Forest Idaho Department of Fish and Game Bureau of Land Management Sagewillow, Inc. F'ORWARD AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document representsthe culmination of a cooperative effort by several agenciesand individuals over a sevenyear period. The field work was fundedby the U.S. ForestService, Bureau of Land Managemen! and Idaho Department of Fish and Game. The U.S. Forest Service, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Bureau of Land Management,and Idaho Division of Environmental Quality provided personnel and equipment for field work. The data analysis and report preparationwas funded by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game and the U.S. Forest Service. Additional funding was provided by Sagewillow, Inc, a landowner in the Little Lost River drainage. Mike Foster,Lost River RangerDistrict, Salmonand Challis National Forests;Bob Martin, Upper SnakeRegion, Idaho Department of Fish and Game; Mark Gamblin, Upper SnakeRegion, Idaho Department of Fish and Game; Pat Koelsch, Idaho Falls District, Bureau of Land Management; and Leon Jadlowski, Salmon and Challis National Forests each provided helpful reviews of the manuscript. Without this cooperative effort, this study and report would not have been possible. The authorwishes to expressappreciation to the following individuals who assistedin the completion ofthis project. USDA Forest Service Daryl Moss - assistingwith -

IGNITE Presentation Abstracts

IGNITE Presentation Abstracts PELICAN MANAGEMENT AND YELLOWSTONE CUTTHROAT TROUT RECOVERY ON THE UPPER BLACKFOOT RIVER: WHERE WE WERE, WHERE WE ARE, AND WHERE WE ARE GOING Arnie Brimmer Idaho Department of Fish and Game Historically, the upper Blackfoot River was one of the most productive systems for Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout and supported a fishery of annual harvest yields in excess of 15,000 fish. This high level of angler exploitation was unsustainable and resulted in the collapse of the fishery in the early 1980’s. Subsequent research supported changes in angling regulations to “no harvest” in the early 1990’s. Within two Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout generations, the fishery had begun to recover. This improvement coincided with the arrival of American White Pelicans in 2002. Since then, Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout adult spawner abundance has declined and remains depressed. In 2009, an American White Pelican Management Plan was developed by the state to address high predation rates on Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout by American White Pelicans. Since then, American White Pelican predation rates of adult spawners in the lower river have been reduced from 30% to less than 5%. Unfortunately, predation on Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout occupying the upper river on the Blackfoot River Wildlife Management Area is still of concern. Predation rates in this section of the river remain at 38% or above. The management activities that we have used successfully on the lower river have proved largely ineffective upriver. Follow along with me as I describe our current and future plans to reduce predation rates on up-river Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout. PRESPAWN MOVEMENTS OF ADULT PACIFIC LAMPREY IN THE CLEARWATER RIVER BASIN John Erhardt1, Doug Nemeth, Michael Murray1, Tod Sween1 1U.S. -

Fish Specialist Report for the Sawmill Canyon Vegetation

Fish Specialist Report for the Sawmill Canyon Vegetation Management Project Lost River Ranger District Salmon-Challis National Forest Custer County and Lemhi County, Idaho T12N, R25E, Sections 1 and 2; T12N, R26E, Sections 5-8; T13N, R25E, Sections 25 and 36; T13N, R26E, Sections 30 and 31 (Boise Meridian) Prepared by: Signature: Date: March 21, 2015 Bart L. Gamett South Zone Fish Biologist Salmon-Challis National Forest Signature: Date: March 21, 2015 Caselle L. Wood Fish Technician Salmon-Challis National Forest 0 1. Introduction The Sawmill Canyon Vegetation Management Project is located in the Sawmill Canyon drainage approximately 35 miles northeast of Mackay (Figure 1). This document is a specialist report that addresses fish related topics associated with this project. The report is organized into the following sections: 1. Introduction 2. Alternatives 3. Issue Analysis 4. Effects to Fish Species with Special Designations 5. Compliance with the Forest Plan and INFISH 2. Alternatives This section of the specialist report describes each of the alternatives associated with the project. The Forest is analyzing three alternatives for this project: 1) no action alternative (with wildfire), 2) the proposed action, and 3) helicopter logging alternative. Each of these is described in detail below. A. No Action Alternative Under this alternative, the Forest Service would not implement the Sawmill Canyon Vegetation Management Project. Natural and man caused processes would continue until an agent of change disrupts the vegetation patterns across the management area. Since 2000 the Salmon- Challis National Forest has experienced many agents of change including a mountain pine beetle epidemic, a spruce bud worm epidemic, loss of subalpine fir through a defoliator, and several fires of over 5,000 acres including one that was over 160,000 acres.