The Origins of British Studio Pottery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Potterõ S Pots, by Suze Lindsay Clay Culture

Cover: Bryan Hopkins functional constructions Spotlight: A Potter s Pots, by Suze Lindsay Clay Culture: An Exploration of Jun ceramics Process: Lauren Karle s folded patterns em— robl ever! p a Mark Issenberg, Lookout M ” ountain d 4. Pottery, 7 Risin a 9 g Faw h 1 n, GA r in e it v t e h n g s u a o h b t I n e r b y M “ y t n a r r a w r a e y 10 (800) 374-1600 • www.brentwheels.com a ith el w The only whe www.ceramicsmonthly.org october 2012 1 “I have a Shimpo wheel from the 1970’s, still works well, durability is important for potters” David Stuempfle www.stuempflepottery.com 2 october 2012 www.ceramicsmonthly.org www.ceramicsmonthly.org october 2012 3 MONTHLY ceramic arts bookstore Editorial [email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5867 fax: (614) 891-8960 editor Sherman Hall associate editor Holly Goring associate editor Jessica Knapp editorial assistant Erin Pfeifer technical editor Dave Finkelnburg online editor Jennifer Poellot Harnetty Advertising/Classifieds [email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5834 fax: (614) 891-8960 classifi[email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5843 advertising manager Mona Thiel advertising services Jan Moloney Marketing telephone: (614) 794-5809 marketing manager Steve Hecker Subscriptions/Circulation customer service: (800) 342-3594 [email protected] Design/Production production editor Melissa Bury production assistant Kevin Davison design Boismier John Design Editorial and advertising offices 600 Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, Ohio 43082 Publisher Charles Spahr Editorial Advisory Board Linda Arbuckle; Professor, Ceramics, Univ. -

Long Gallery Educator’S Pack This Pack Contains Information Regarding the Contents and Themes of the Objects in the Long Gallery

Long Gallery Educator’s Pack This pack contains information regarding the contents and themes of the objects in the Long Gallery. On our website you can find further activities and resources to explore. The first exhibition in this gallery, ’Reactions’ focuses on Dundee’s nationally important collection of studio ceramics. This pack explores some of the processes that have created the stunning pieces on display and shares some of the inspirations behind the creation of individual ceramics. Contents Reactions: Studio Ceramics from our Collection Introduction and Origins 01 Studio Pottery - Influences 02 The Process 03 Glossary 05 List of Objects - by theme What is Studio Pottery? 10 Influences 11 Ideas and Stories 14 What on Earth is Clay? 16 Getting your Hands Dirty 19 The Icing on the Cake - Glaze and Decoration 21 Fire 24 Artist Focus Stephen Bird 27 Reactions: Studio Ceramics from our collection Introduction- background and beginnings 'Studio Ceramics' or 'Studio Pottery' - can be best described as the making of clay forms by hand in a small studio rather than in a factory. Where the movement in the early days is referred to as 'Studio Pottery' due to its focus on functional vessels and 'pots', the name of 'Studio Ceramics' now refers broadly to include work by artists and designers that may be more conceptual or sculptural rather than functional. As an artistic movement Studio Ceramics has a peculiar history. It is a history that includes changes in artistic and public taste, developments in art historical terms and small and very individual stories of artists and potters. -

HO060710 Sale

For Sale by Auction to be held at Dowell Street, Honiton Tel 01404 510000 Fax 01404 44165 th Tuesday 6 July 2010 Ceramics, Glass & Oriental, Works of Art, Collectables & Pictures Furniture SALE COMMENCES AT 10.00am yeer Buyers are reminded to check the ‘Saleroom Notice’ for information regarding WITHDRAWN LOTS and EXTRA LOTS SALE REFERENCE HO09 Catalogues £1.50 On View: Order of Sale: Saturday 3rd July 9.00am – 12.00 Ceramics, Glass & Oriental Monday 5th July 9.00am – 7.00pm Lots 1 - 126 Morning of Sale from 9.00am Pictures Lots 131 - 195 Works of Art & Collectables Lots 200 - 361 Carpets, Rugs & Furniture Lots 362 - 508 TUESDAY 6TH JULY 2010 Sale commences at 10am. CERAMICS, GLASS & ORIENTAL 1. A pair of bookend flower vases in Whitefriars style. 2. A bohemian style green and clear glass vase, of trumpet shape, painted with floral sprays and gilt embellishment, 17cm high. 3. A pair of overlaid ruby glass decanters with floral knop stoppers. 4. An amber and milk glass globular vase, probably Stourbridge with vertical fluted decoration, 15cm high. 5. A pair of cut glass decanters with stoppers and one other. 6. A quantity of Carnival and other moulded glassware. 7. A quantity of cut and other glass. 8. A part suite of cut glass to include tumblers and wine glasses. 9. A quantity of various drinking glasses and glass ware. 10. A pair of cut glass decanters, two other decanters and stoppers, six tumblers and five brandy balloons. 11. A collection of twenty five various glass paperweights to include millefiore style paperweights, floral weights, candlestick and others. -

Evelyn De Morgan Y La Hermandad Prerrafaelita

Trabajo Fin de Grado Lux in Tenebris: Evelyn De Morgan y la Hermandad Prerrafaelita Lux in Tenebris: Evelyn De Morgan and the Pre- Raphaelite Brotherhood. Autor/es Irene Zapatero Gasco Director/es Concepción Lomba Serrano Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Curso 2018/2019 LUX IN TENEBRIS: EVELYN DE MORGAN Y LA HERMANDAD PRERRAFAELITA IRENE ZAPATERO GASCO DIRECTORA: CONCEPCIÓN LOMBA SERRANO HISTORIA DEL ARTE, 2019 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN - JUSTIFICACIÓN DEL TRABAJO…………………………………....1 - OBJETIVOS…………………………………………………………....2 - METODOLOGÍA……………………………………………………....2 - ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN………………………………………....3 - AGRADECIMIENTOS………………………………………………...5 LA ÉPOCA VICTORIANA - CONTEXTO HISTORICO…………………………………………….6 - EL PAPEL QUE DESEMPEÑABA LA MUJER EN LA SOCIEDAD…………………………………………………………….7 LA HERMANDAD PRERRAFAELITA…………………………………...10 EVELYN DE MORGAN - TRAYECTORIA E IDEOLOGÍA ARTÍSTICA……………………...13 - EL IDEAL ICÓNICO RECREADO…………………..……………....15 - LA REPRESENTACIÓN DE LA MUJER EN SU PRODUCCIÓN ARTÍSTICA...........................................................................................16 I. EL MUNDO ESPIRITUAL…………………………………...17 II. HEROÍNAS SAGRADAS…………………………………….21 III. ANTIBELICISTAS…………………………………………....24 CONCLUSIONES…………...……………………………………………….26 BIBLIOGRAFÍA Y WEBGRAFÍA…………………………………………28 ANEXOS….……………………………………………………………..........32 - REPERTORIOGRÁFICO…………………………………………….46 INTRODUCCIÓN JUSTIFIACIÓN DEL TRABAJO Centrado en la obra de la pintora Evelyn De Morgan (1855, Londres) nuestro trabajo pretende revisar su producción artística contextualizándola -

Exhibitions & Events

Events for Adults at a Glance Forthcoming Exhibitions Pricing and online booking at yorkartgallery.org.uk. Discover more and buy tickets at yorkartgallery.org.uk. FREE TALKS – no need to book Grayson Perry: The Pre-Therapy Years EXHIBITIONS Opens 12 June 2020 Curator’s Choice The first exhibition to & EVENTS Third Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. survey Grayson Perry’s earliest forays into the art February – May 2020 Friends of York Art Gallery Lunchtime Talks world will re-introduce the Second Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. explosive and creative 14 Feb – 31 May 2020 works he made between Plan your visit… Visitor Experience Team Talks 1982 and 1994. These Every day between 2pm – 3pm (except Wednesday ground-breaking ‘lost’ pots OPEN DAILY: 10am – 5pm and Saturday). will be reunited for the first time to focus on the York Art Gallery York Art Gallery is approximately Kindly Supported by Automaton Clock Talk and Demonstration Exhibition Square, York YO1 7EW 15 minutes walk from York Railway formative years of one of T: 01904 687687 Station. From the station, cross the Harland Miller, Ace, 2017. © Harland Miller. Photo © White Cube (George Darrell). Wednesday and Saturday: 2pm – 2.30pm. Britain’s most recognisable E: [email protected] river and walk towards York Minster. artists. The nearest car parks are Bootham Row and Marygate, which are a five WORKSHOPS – book online Touring exhibition from minute walk from York Art Gallery. The Holburne Museum Aesthetica Art Prize 2020 Tickets can be purchased in advance or on arrival. For pricing and to book your Sketchbook Circle Image: Grayson Perry, Cocktail Party, 1989 © Grayson Perry. -

Fast Fossils Carbon-Film Transfer on Saggar-Fired Porcelain by Dick Lehman

March 2000 1 2 CERAMICS MONTHLY March 2000 Volume 48 Number 3 “Leaves in Love,” 10 inches in height, handbuilt stoneware with abraded glaze, by Michael Sherrill, Hendersonville, North FEATURES Carolina. 34 Fast Fossils 40 Carbon-Film Transfer on Saggar-Fired Porcelain by Dick Lehman 38 Steven Montgomery The wood-firing kiln at Buck Industrial imagery with rich texture and surface detail Pottery, Gruene, Texas. 40 Michael Sherrill 62 Highly refined organic forms in porcelain 42 Rasa and Juozas Saldaitis by Charles Shilas Lithuanian couple emigrate for arts opportunities 45 The Poetry of Punchong Slip-Decorated Ware by Byoung-Ho Yoo, Soo-Jong Ree and Sung-Jae Choi by Meghen Jones 49 No More Gersdey Borateby JejfZamek Why, how and what to do about it 51 Energy and Care Pit Firing Burnished Pots on the Beach by Carol Molly Prier 55 NitsaYaffe Israeli artist explores minimalist abstraction in vessel forms “Teapot,” approximately 9 inches in height, white 56 A Female Perspectiveby Alan Naslund earthenware with under Female form portrayed by Amy Kephart glazes and glazes, by Juozas and Rasa Saldaitis, 58 Endurance of Spirit St. Petersburg, Florida. The Work of Joanne Hayakawa by Mark Messenger 62 Buck Pottery 42 17 Years of Turnin’ and Burnin’ by David Hendley 67 Redware: Tradition and Beyond Contemporary and historical work at the Clay Studio “Bottle,” 7 inches in height, wheel-thrown porcelain, saggar 68 California Contemporary Clay fired with ferns and sumac, by The cover:“Echolalia,” San Francisco invitational exhibition Dick Lehman, Goshen, Indiana. 29½ inches in height, press molded and assembled, 115 Conquering Higher Ground 34 by Steven Montgomery, NCECA 2000 Conference Preview New York City; see page 38. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS FOR THE LOVE OF PIE LINDA M. N. STRUBLE Spring 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Art with honors in Art Reviewed and approved* by the following: Del Harrow Assistant Professor of Art Thesis Supervisor Jerrold Maddox Professor of Art Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT For my senior research project I hosted the event For the Love of Pie in the Patterson Gallery of the Pennsylvania State University. I combined pottery, painting, and pastry to create pieces that encouraged attendees to interact with the objects in the gallery and to interact with each other. These interactions or relations became the ultimate component of my work. I wanted to elevate pie. So, I experimented with earthenware to develop different surface textures that created an aesthetic bridge between the ceramics and the pastries. In addition to pie, I incorporated elaborate desserts--croquembouche and kransekake. My work is ornate in the sense that it is composed of layers of complexity that engage multiple senses. I have a long history with pies and pastries, but I needed to look elsewhere for inspiration for the other elements of my work. Giorgio Morandi, Betty Woodman, and Luca Della Robbia provided plenty and I created works after each of these artists. Nicolas Bourriaud and Rirkrit Tiravanija introduced me to the concept of relational aesthetics while Gordon Matta-Clark’s ventures in aspic bolstered my reserve and helped me to articulate my goals. -

9. Ceramic Arts

Profile No.: 38 NIC Code: 23933 CEREMIC ARTS 1. INTRODUCTION: Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take forms including art ware, tile, figurines, sculpture, and tableware. Ceramic art is one of the arts, particularly the visual arts. Of these, it is one of the plastic arts. While some ceramics are considered fine art, some are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramics may also be considered artifacts in archaeology. Ceramic art can be made by one person or by a group of people. In a pottery or ceramic factory, a group of people design, manufacture and decorate the art ware. Products from a pottery are sometimes referred to as "art pottery".[1] In a one-person pottery studio, ceramists or potters produce studio pottery. Most traditional ceramic products were made from clay (or clay mixed with other materials), shaped and subjected to heat, and tableware and decorative ceramics are generally still made this way. In modern ceramic engineering usage, ceramics is the art and science of making objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials by the action of heat. It excludes glass and mosaic made from glass tesserae. There is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures. Elements of ceramic art, upon which different degrees of emphasis have been placed at different times, are the shape of the object, its decoration by painting, carving and other methods, and the glazing found on most ceramics. 2. -

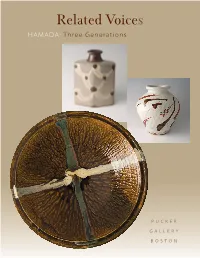

Related Voices Hamada: Three Generations

Related Voices HAMADA: Three Generations PUCKER GALLERY BOSTON Tomoo Hamada Shoji Hamada Bottle Obachi (Large Bowl), 1960-69 Black and kaki glaze with akae decoration Ame glaze with poured decoration 12 x 8 ¼ x 5” 4 ½ x 20 x 20” HT132 H38** Shinsaku Hamada Vase Ji glaze with tetsue and akae decoration Shoji Hamada 9 ¾ x 5 ¼ x 5 ¼” Obachi (Large Bowl), ca. 1950s HS36 Black glaze with trailing decoration 5 ½ x 23 x 23” H40** *Box signed by Shoji Hamada **Box signed by Shinsaku Hamada All works are stoneware. Three Voices “To work with clay is to be in touch with the taproot of life.’’ —Shoji Hamada hen one considers ceramic history in its broadest sense a three-generation family of potters isn’t particularly remarkable. Throughout the world potters have traditionally handed down their skills and knowledge to their offspring thus Wmaintaining a living history that not only provided a family’s continuity and income but also kept the traditions of vernacular pottery-making alive. The long traditions of the peasant or artisan potter are well documented and can be found in almost all civilizations where the generations are to be numbered in the tens or twenties or even higher. In Africa, South America and in Asia, styles and techniques remained almost unaltered for many centuries. In Europe, for example, the earthenware tradition existed from the early Middle Ages to the very beginning of the 20th century. Often carried on by families primarily involved in farming, it blossomed into what we would now call the ‘slipware’ tradition. The Toft family was probably the best known makers of slipware in Staffordshire. -

Review of the Year 2012–2013

review of the year TH E April 2012 – March 2013 NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY review of the year April 2012 – March 2013 published by order of the trustees of the national gallery london 2013 Contents Introduction 5 Director’s Foreword 6 Acquisitions 10 Loans 30 Conservation 36 Framing 40 Exhibitions 56 Education 57 Scientific Research 62 Research and Publications 66 Private Support of the Gallery 70 Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 74 Financial Information 74 National Gallery Company Ltd 76 Fur in Renaissance Paintings 78 For a full list of loans, staff publications and external commitments between April 2012 and March 2013, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/ annual-review the national gallery review of the year 2012– 2013 introduction The acquisitions made by the National Gallery Lucian Freud in the last years of his life expressed during this year have been outstanding in quality the hope that his great painting by Corot would and so numerous that this Review, which provides hang here, as a way of thanking Britain for the a record of each one, is of unusual length. Most refuge it provided for his family when it fled from come from the collection of Sir Denis Mahon to Vienna in the 1930s. We are grateful to the Secretary whom tribute was paid in last year’s Review, and of State for ensuring that it is indeed now on display have been on loan for many years and thus have in the National Gallery and also for her support for very long been thought of as part of the National the introduction in 2012 of a new Cultural Gifts Gallery Collection – Sir Denis himself always Scheme, which will encourage lifetime gifts of thought of them in this way. -

The Leach Pottery: 100 Years on from St Ives

The Leach Pottery: 100 years on from St Ives Exhibition handlist Above: Bernard Leach, pilgrim bottle, stoneware, 1950–60s Crafts Study Centre, 2004.77, gift of Stella and Nick Redgrave Introduction The Leach Pottery was established in St Ives, Cornwall in the year 1920. Its founders were Bernard Leach and his fellow potter Shoji Hamada. They had travelled together from Japan (where Leach had been living and working with his wife Muriel and their young family). Leach was sponsored by Frances Horne who had set up the St Ives Handicraft Guild, and she loaned Leach £2,500 as capital to buy land and build a small pottery, as well as a sum of £250 for three years to help with running costs. Leach identified a small strip of land (a cow pasture) at the edge of St Ives by the side of the Stennack stream, and the pottery was constructed using local granite. A tiny room was reserved for Hamada to sleep in, and Hamada himself built a climbing kiln in the oriental style (the first in the west, it was claimed). It was a humble start to one of the great sites of studio pottery. The Leach Pottery celebrates its centenary year in 2020, although the extensive programme of events and exhibitions planned in Britain and Japan has been curtailed by the impact of Covid-19. This exhibition is the tribute of the Crafts Study Centre to the history, legacy and continuing significance of The Leach Pottery, based on the outstanding collections and archives relating firstly to Bernard Leach. -

Exhibitions & Events

Events for Adults at a Glance Forthcoming Exhibitions Pricing and online booking at yorkartgallery.org.uk. Discover more and buy tickets at yorkartgallery.org.uk. Exhibitions FREE TALKS – no need to book Harland Miller: York, So Good They Named It Once Curator’s Choice 14 February – 31 May 2020 & Events Third Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. York Art Gallery presents a mid-career exhibition of York- Friends of York Art Gallery Lunchtime Talks born artist Harland Miller. The largest solo presentation October 2019 – January 2020 of his work to date, it celebrates his relationship to the Second Wednesday of the month: 12.30pm – 1pm. city of his upbringing. Alongside more recent works, Plan your visit… Visitor Experience Team Talks it will feature a selection of Miller’s acclaimed classic Penguin series and ‘bad weather paintings’ which playfully Every day between 2pm – 3pm (except Wednesday Dieric Bouts (c.1415 – 1475), Christ Crowned with Thorns, c.1470 © The National Gallery, London. reference various cities in the North of England, evoking and Saturday). OPEN DAILY: 10am – 5pm Bequeathed by Mrs Joseph H. Green, 1880 a tragicomic sense of time and place. York Art Gallery York Art Gallery is approximately The Making a Masterpiece: Bouts and Beyond (1450 – 2020) exhibition has been made possible as a result of the Automaton Clock Talk and Demonstration Supported by White Cube Exhibition Square, York YO1 7EW 15 minutes walk from York Railway Government Indemnity Scheme. York Art Gallery would like to thank HM Government for providing Government T: 01904 687687 Station. From the station, cross the Indemnity and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and Arts Council England for arranging the indemnity.