Sjöström's the Wind and the Transcendental Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Annual Report

Annual Report 2018 Dear Friends, welcome anyone, whether they have worked in performing arts and In 2018, The Actors Fund entertainment or not, who may need our world-class short-stay helped 17,352 people Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund is here for rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational and speech)—all with everyone in performing arts and entertainment throughout their the goal of a safe return home after a hospital stay (p. 14). nationally. lives and careers, and especially at times of great distress. Thanks to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, Our programs and services Last year overall we provided $1,970,360 in emergency financial stronger than ever and is here for those who need us most. Our offer social and health services, work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as ANNUAL REPORT assistance for crucial needs such as preventing evictions and employment and training the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. paying for essential medications. We were devastated to see programs, emergency financial the destruction and loss of life caused by last year’s wildfires in assistance, affordable housing, 2018 California—the most deadly in history, and nearly $134,000 went In addition, Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS continues to be our and more. to those in our community affected by the fires and other natural steadfast partner, assuring help is there in these uncertain times. disasters (p. 7). Your support is part of a grand tradition of caring for our entertainment and performing arts community. Thank you Mission As a national organization, we’re building awareness of how our CENTS OF for helping to assure that the show will go on, and on. -

275. – Part One

275. – PART ONE 275. Clifford (1994) Okay, here’s the deal: I don’t know you, you don’t know me, but if you are anywhere near a television right now I need you to stop whatever it is that you’re doing and go watch “Clifford” on HBO Max. This is another film that has a 10% score on Rotten Tomatoes which just leads me to believe that all of the critics who were popular in the nineties didn’t have a single shred of humor in any of their non-existent funny bones. I loved this movie when I was seven, and I love it even more when I’m thirty-three. It’s genius. Martin Short (who at the time was forty-four) plays a ten-year-old hyperactive nightmare child from hell. I mean it, this kid might actually be the devil. He is straight up evil, conniving, manipulative and all-told probably causes no less than ten million dollars-worth of property damage. And, again, the plot is so simple – he just wants to go to Dinosaur World. There are so many comedy films with such complicated plots and motivations for their characters, but the simplistic genius of “Clifford” is just this – all this kid wants on the entire planet is to go to Dinosaur World. That’s it. The movie starts with him and his parents on an plane to Hawaii for a business trip, and Clifford knows that Dinosaur Land is in Los Angeles, therefore he causes so much of a ruckus that the plane has to make an emergency landing. -

Imitation of Life

Genre Films: OLLI: Spring 2021: weeks 5 & 6 week 5: IMITATION OF LIFE (1959) directed by Douglas Sirk; cast: Lana Turner, John Gavin, Sandra Dee, Juanita Moore, Susan Kohner, Dan O'Herlihy, Troy Donahue, Robert Alda Richard Brody: new yorker .com: “For his last Hollywood film, released in 1959, the German director Douglas Sirk unleashed a melodramatic torrent of rage at the corrupt core of American life—the unholy trinity of racism, commercialism, and puritanism. The story starts in 1948, when two widowed mothers of young daughters meet at Coney Island: Lora Meredith (Lana Turner), an aspiring actress, who is white, and Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore), a homeless and unemployed woman, who is black. The Johnsons move in with the Merediths; Annie keeps house while Lora auditions. A decade later, Lora is the toast of Broadway and Annie (who still calls her Miss Lora) continues to maintain the house. Meanwhile, Lora endures troubled relationships with a playwright (Dan O’Herlihy), an adman (John Gavin), and her daughter (Sandra Dee); Annie’s light-skinned teen-age daughter, Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner), is working as a bump-and-grind showgirl and passing as white, even as whites pass as happy and Annie exhausts herself mastering her anger and maintaining her self-control. For Sirk, the grand finale was a funeral for the prevailing order, a trumpet blast against social façades and walls of silence. The price of success, in his view, may be the death of the soul, but its wages afford retirement, withdrawal, and contemplation—and, upon completing the film, that’s what Sirk did.” Charles Taylor: villagevoice.com: 2015: “Fifty-six years after it opened, Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life … remains the apotheosis of Hollywood melodrama — as Sirk’s final film, it could hardly be anything else — and the toughest-minded, most irresolvable movie ever made about race in this country. -

2017 Annual Report

Annual 2017 Report Our ongoing investment into increasing services for the senior In 2017, The Actors Fund Dear Friends, members of our creative community has resulted in 1,474 senior and helped 13,571 people in It was a challenging year in many ways for our nation, but thanks retired performing arts and entertainment professionals served in to your generous support, The Actors Fund continues, stronger 2017, and we’re likely to see that number increase in years to come. 48 states nationally. than ever. Our increased activities programming extends to Los Angeles, too. Our programs and services With the support of The Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, The Actors Whether it’s our quick and compassionate response to disasters offer social and health services, Fund started an activities program at our Palm View residence in West ANNUAL REPORT like the hurricanes and California wildfires, or new beginnings, employment and training like the openings of The Shubert Pavilion at The Actors Fund Hollywood that has helped build community and provide creative outlets for residents and our larger HIV/AIDS caseload. And the programs, emergency financial Home (see cover photo), a facility that provides world class assistance, affordable housing 2017 rehabilitative care, and The Friedman Health Center for the Hollywood Arts Collective, a new affordable housing complex and more. Performing Arts, our brand new primary care facility in the heart aimed at the performing arts community, is of Times Square, The Actors Fund continues to anticipate and in the development phase. provide for our community’s most urgent needs. Mission Our work would not be possible without an engaged Board as well as the efforts of our top notch staff and volunteers. -

The Imitation of Life Activities Sara Jane: 1. in the Much Discussed Final

The Imitation of Life Activities Sara Jane: 1. In the much discussed final scene of Douglas Sirk's IMITATION OF LIFE (1959), Sara Jane Johnson (Susan Kohner) breaks through the crowd watching an extravagant funeral procession, pushes aside a policeman, and pulls open the doors of a horse-drawn hearse, crying, "I have killed my mother." a. How has Sara Jane “killed her mother”? b. How can this specific feeling of grief and regret impact the rest of her life? c. Although Annie Johnson loved her daughter dearly, was this love enough for Sara Jane? 2. Sara Jane challenges the limitations of' her identity. Refusing to be either a proper lady or a proper African-American/black girl, Sara Jane throughout the film enacts a series of "imitations". a. Identify 2 examples in which Sara Jane “pretends” or carries out some type of “imitation”. b. How does Annie Johnson feel about people pretending or being ashamed of who they are and where they come from? 3. Article about one of the characters from the original 1933 version of the movie. http://www.angelfire.com/jazz/ninamaemckinney/FrediWashington.html - anything but an imitation of life. 4. Memorable quotes from the movie. Select 2 quotes from any characters and write a 2-3 sentence response/reaction. What does the quote mean? How is it connected to the theme of the movie? Can you relate to the quote for a specific reason? Discuss any 2 quotes that stirred some type of reaction out of you (either good or bad). http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0052918/quotes a. -

Film Essay for “The Wind”

The Wind By Fritzi Kramer “The Wind” is legendary for its raw emotional power, its skillful direction and the triumphant performances of its leads. Lillian Gish, Lars Hanson and director Victor Sjöström (credited during his time in Hollywood as “Seastrom”) had previously worked together on “The Scarlet Letter” (1926), a creative and commer- cial hit, and Gish had chosen a psychological west- ern written by Texas native Dorothy Scarborough as their next vehicle. The novel focuses on Letty, a so- phisticated Virginia girl who is forced to relocate to a remote ranch in Texas. Driven to the brink of mad- ness by the harsh weather and unceasing wind, Letty’s situation becomes worse when circumstanc- es force her to accept a marriage proposal from Lige, a rough cowboy. Roddy, a sophisticated city man, takes advantage of Letty’s fragile mental stage and rapes her. Letty responds by shooting him and then races outside, giving herself to the wind. It’s easy to see the appeal of this intense work, especial- ly in the visual medium of silent film. Gish later wrote that playing innocent heroines, roles she sarcastically described as “Gaga-baby,” was an enormous challenge.1 So much sweetness and light could quickly bore audiences if it wasn’t played just right but a villain could ham things up with impunity. Gish had dabbled in different parts, playing a street- wise tenement dweller in “The Musketeers of Pig Alley” (1912) and a heartless vamp in the lost film “Diane of the Follies” (1916), but film audiences were most taken with her more delicate creations. -

For Immediate Release December 2001 the MUSEUM of MODERN

MoMA | Press | Releases | 2001 | Mauritz Stiller Page 1 of 6 For Immediate Release December 2001 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART PAYS TRIBUTE TO SWEDISH SILENT FILMMAKER MAURITZ STILLER Mauritz Stiller—Restored December 27, 2001–January 8, 2002 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1 NEW YORK, DECEMBER 2001–The Museum of Modern Art’s Film and Media Department is proud to present Mauritz Stiller—Restored from December 27, 2001 through January 8, 2002, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theater 1. Most films in the exhibition are new prints, including five newly restored 35mm prints of Stiller’s films from the Swedish Film Institute. All screenings will feature simultaneous translation by Tana Ross and live piano accompaniment by Ben Model or Stuart Oderman. The exhibition was organized by Jytte Jensen, Associate Curator, Department of Film and Media, and Edith Kramer, Director, The Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, in collaboration with Jon Wengström, Curator, Cinemateket, the Swedish Film Institute, Stockholm. The period between 1911 and 1929 has been called the golden age of Swedish cinema, a time when Swedish films were seen worldwide, influencing cinematic language, inspiring directors in France, Russia, and the United States, and shaping audience expectations. Each new release by the two most prominent Swedish directors of the period—Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller—was a major event that advanced the art of cinema. "Unfortunately, Stiller is largely remembered as the man who launched Greta Garbo and as the Swede who didn’t make it in Hollywood," notes -

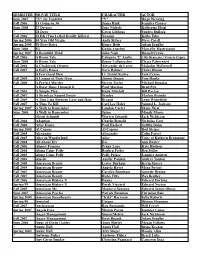

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Arrival of a Group of Important Films from Sweden 1937

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART |1 WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 7.7470 F°R RELEASE TUESDAY, APRIL 27, 1937 The Museum of Modern Art announces the appointment of Mrs. Dwight Davis of Washington, D. C. as Out-of-town Chairman of its Membership Committee for that city. Mrs. Davis has invited prominent residents of Washington who are in terested in the arts and particularly in modern art, to her home Monday afternoon, May 3rd, to meet Mr. A. Conger G-oodyear, President of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Mr. G-oodyear will talk on contemporary art and the work of the Museum. The Museum of Modern Art was founded in the Fall of 1929 and, although it has its headquarters in New York City, it has never been merely a local institution. Nearly half of its members live more than seventy-five miles away from New York City and it has Out-of-town chairmen who form the nucleus of membership groups in Buffalo, New York; Chicago, Illinois, Cincinnati, Ohio; Cleveland, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; Hartford, Connecticut; Houston, Texas; Louisville, Kentucky; Minneapolis, Minnesota; New Haven, Connecticut; Palm Beach, Florida; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Princeton, New Jersey; Providence, Rhode Island; Rochester, New York; San Francisco, California; St. Louis, Missouri; St. Paul, Minnesota; State of Vermont; Washington, D. C; Waterbury, Connecticut; and Worcester, Massachusetts. Out-of-town members are constantly in touch with all the activities of the Museum through its bulletins and the large, comprehensively illustrated books of each of its major exhibitions during the year. -

Silent Film Music and the Theatre Organ Thomas J. Mathiesen

Silent Film Music and the Theatre Organ Thomas J. Mathiesen Introduction Until the 1980s, the community of musical scholars in general regarded film music-and especially music for the silent films-as insignificant and uninteresting. Film music, it seemed, was utili tarian, commercial, trite, and manipulative. Moreover, because it was film music rather than film music, it could not claim the musical integrity required of artworks worthy of study. If film music in general was denigrated, the theatre organ was regarded in serious musical circles as a particular aberration, not only because of the type of music it was intended to play but also because it represented the exact opposite of the characteristics espoused by the Orgelbewegung of the twentieth century. To make matters worse, many of the grand old motion picture theatres were torn down in the fifties and sixties, their music libraries and theatre organs sold off piecemeal or destroyed. With a few obvious exceptions (such as the installation at Radio City Music Hall in New (c) 1991 Indiana Theory Review 82 Indiana Theory Review Vol. 11 York Cityl), it became increasingly difficult to hear a theatre organ in anything like its original acoustic setting. The theatre organ might have disappeared altogether under the depredations of time and changing taste had it not been for groups of amateurs that restored and maintained some of the instruments in theatres or purchased and installed them in other locations. The American Association of Theatre Organ Enthusiasts (now American Theatre Organ Society [ATOS]) was established on 8 February 1955,2 and by 1962, there were thirteen chapters spread across the country. -

Popular Culture Imaginings of the Mulatta: Constructing Race, Gender

Popular Culture Imaginings of the Mulatta: Constructing Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Nation in the United States and Brazil A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Jasmine Mitchell IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Bianet Castellanos, Co-adviser Erika Lee, Co-adviser AUGUST 2013 © Jasmine Mitchell 2013 Acknowledgements This dissertation would have been impossible without a community of support. There are many numerous colleagues, family, friends, and mentors that have guided ths intellectual and personal process. I would first like to acknowledge my dissertation committee for their patience, enthusiasm, and encouragement while I was in Minneapolis, New York, São Paulo, and everywhere in between. I am thankful for the research and methodological expertise they contributed as I wrote on race, gender, sexuality, and popular culture through an interdisciplinary and hemispheric approach. Special gratitude is owed to my co-advisors, Dr. Bianet Castellanos and Dr. Erika Lee for their guidance, commitment, and willingness to read and provide feedback on multiple drafts of dissertation chapters and applications for various grants and fellowships to support this research. Their wisdom, encouragement, and advice for not only this dissertation, but also publications, job searches, and personal affairs were essential to my success. Bianet and Erika pushed me to rethink the concepts used within the dissertation, and make more persuasive and clearer arguments. I am also grateful to my other committee members, Dr. Fernando Arenas, Dr. Jigna Desai, and Dr. Roderick Ferguson, whose advice and intellectual challenges have been invaluable to me. -

Films with 2 Or More Persons Nominated in the Same Acting Category

FILMS WITH 2 OR MORE PERSONS NOMINATED IN THE SAME ACTING CATEGORY * Denotes winner [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 3 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1935 (8th) ACTOR -- Clark Gable, Charles Laughton, Franchot Tone; Mutiny on the Bounty 1954 (27th) SUP. ACTOR -- Lee J. Cobb, Karl Malden, Rod Steiger; On the Waterfront 1963 (36th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Diane Cilento, Dame Edith Evans, Joyce Redman; Tom Jones 1972 (45th) SUP. ACTOR -- James Caan, Robert Duvall, Al Pacino; The Godfather 1974 (47th) SUP. ACTOR -- *Robert De Niro, Michael V. Gazzo, Lee Strasberg; The Godfather Part II 2 NOMINATIONS in same acting category 1939 (12th) SUP. ACTOR -- Harry Carey, Claude Rains; Mr. Smith Goes to Washington SUP. ACTRESS -- Olivia de Havilland, *Hattie McDaniel; Gone with the Wind 1941 (14th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Patricia Collinge, Teresa Wright; The Little Foxes 1942 (15th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Dame May Whitty, *Teresa Wright; Mrs. Miniver 1943 (16th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Gladys Cooper, Anne Revere; The Song of Bernadette 1944 (17th) ACTOR -- *Bing Crosby, Barry Fitzgerald; Going My Way 1945 (18th) SUP. ACTRESS -- Eve Arden, Ann Blyth; Mildred Pierce 1947 (20th) SUP. ACTRESS -- *Celeste Holm, Anne Revere; Gentleman's Agreement 1948 (21st) SUP. ACTRESS -- Barbara Bel Geddes, Ellen Corby; I Remember Mama 1949 (22nd) SUP. ACTRESS -- Ethel Barrymore, Ethel Waters; Pinky SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Elsa Lanchester; Come to the Stable 1950 (23rd) ACTRESS -- Anne Baxter, Bette Davis; All about Eve SUP. ACTRESS -- Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter; All about Eve 1951 (24th) SUP. ACTOR -- Leo Genn, Peter Ustinov; Quo Vadis 1953 (26th) ACTOR -- Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster; From Here to Eternity SUP.