James Webb Throckmorton: the Life and Career

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carceral State: Baton Rouge and Its Plantation Environs Across Emancipation by William Iverson Horne M.A. in History, August

Carceral State: Baton Rouge and its Plantation Environs Across Emancipation by William Iverson Horne M.A. in History, August 2013, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 19, 2019 Dissertation directed by Tyler Anbinder and Andrew Zimmerman Professors of History The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that William Iverson Horne has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of March 6, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Carceral State: Baton Rouge and its Plantation Environs Across Emancipation William Iverson Horne Dissertation Research Committee: Tyler Anbinder, Professor of History, Dissertation Co-Director Andrew Zimmerman, Professor of History and International Affairs, Dissertation Co-Director Erin Chapman, Associate Professor of History, Committee Member Adam Rothman, Professor of History, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2019 by William Iverson Horne All rights reserved iii Dedication I dedicate this work to my family, who supported me from the beginning of this project to its completion. I simply could not have done any of this work without their love and encouragement. My wife Laura has, at every turn, been the best partner one could hope for while our two children, Abigail and Eliza, grounded me in reality and sustained me with their unconditional affection. They reminded me that smiling, laughing, and even crying are absolute treasures. I have learned so much from each of them and remain, above all else, grateful to be “Dad.” iv Acknowledgments Two groups of people made this work possible: the scholars who gave me advice at various stages of the project and my coworkers, neighbors, and friends who shared their stories of struggle and triumph. -

![Shelby Family Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1659/shelby-family-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-411659.webp)

Shelby Family Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered

Shelby Family Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Frank Tusa Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2013 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms013008 Collection Summary Title: Shelby Family Papers Span Dates: 1738-1916 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1757-1829) ID No.: MSS39669 Creator: Shelby family Extent: 2,315 items ; 9 containers ; 2 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Correspondence, memoranda, legal and financial papers, military records, genealogical data, and memorabilia relating mainly to Evan Shelby, soldier and frontiersman, and to his son, Isaac Shelby, soldier and political leader, providing a record of frontier life and political and economic developments in Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Brown, John, 1757-1837--Correspondence. Campbell, Arthur, 1742-1811--Correspondence. Clay, Henry, 1777-1852--Correspondence. Crittenden, John J. (John Jordan), 1787-1863--Correspondence. Greenup, Christopher, 1750-1818--Correspondence. Grigsby, John Warren, 1818-1877--Correspondence. Grigsby, Susan Preston Shelby, 1830-1891--Correspondence. Hardin, Martin D., 1780-1823--Correspondence. Harrison, Benjamin, ca. 1726-1791--Correspondence. Hart, Nathaniel, 1770-1844--Correspondence. Irvine, Susan Hart McDowell, 1803-1834--Correspondence. -

The Texas Constitution, Adopted In

Listen on MyPoliSciLab 2 Study and Review the Pre-Test and Flashcards at myanthrolab The Texas Read and Listen to Chapter 2 at myanthrolab Listen to the Audio File at myanthrolab ConstitutionView the Image at myanthrolab Watch the Video at myanthrolab Humbly invoking the blessings of Almighty God, the people of the State of Texas do ordain and establish this Constitution. Read the Document at myanthrolab —Preamble to the Constitution of Texas 1876 If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, Maneitherp the Concepts at myanthrolab external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.Explore the Concept at myanthrolab —James Madison, Federalist No. 51 Simulate the Experiment at myanthrolab he year was 1874, and unusual events marked the end of the darkest chapter in Texas history—the Reconstruction era and the military occupation that followed the Civil War. Texans, still smarting from some of the most oppressive laws ever T imposed on U.S. citizens, had overwhelmingly voted their governor out of of- fice, but he refused to leave the Capitol and hand over his duties to his elected successor. For several tense days, the city of Austin was divided into two armed camps—those supporting the deposed governor, Edmund J. Davis, and thoseRead supporting the Document the man at my whoanthr defeatedolab Margin sample him at the polls, Richard Coke. -

Smash and Dash

WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE TheTUESDAY | JANUARY 29, 2013Baylor Lariatwww.baylorlariat.com SPORTS Page 5 NEWS Page 3 A&E Page 4 Making milestones It all adds up Ready, set, sing Brittney Griner breaks the NCAA Baylor accounting students Don’t miss today’s opening record for total career blocks. Find out land in the top five of a national performance of the Baylor how she affects the court defensively accounting competition Opera’s ‘Dialogues of Carmelites’ Vol. 115 No. 4 © 2013, Baylor University In Print >> HAND OFF Smash Alumni Association Baylor reacts to former Star Wars director George Lucas passing the director’s torch to J.J. and president under fire Abrams By Sierra Baumbach indirectly communicated to the prosecu- Staff Writer tor who was trying the case,” Polk County Page 4 Criminal District Attorney William Lee dash The 258th State District Judge Eliza- Hon wrote In an e-mail to the Lariat. beth E. Coker, who is also president of >> CALL OUT According to the Chronicle article, Local cemetery the Baylor Alumni Association, is under Polk County Investigator David Wells Get one writer’s opinion review by the Texas Commission on Judi- was sitting beside Jones in the gallery. on player safety and cial Conduct for a text message allegedly Jones asked to borrow Wells’ notepad the future of the NFL plagued by sent during court that was thought to aid and it was from this exchange that Wells following remarks by the prosecution in a felony charge of in- discovered the interaction between Cok- President Obama and vandalism jury to a child. -

APRIL 2018 At

24 Non-Profit APR U.S. Postage PAID APRIL 2018 Louisville, KY at THE FILSON Permit No. 927 1310 S. 3rd St. Louisville, KY 40208 18 APR www.filsonhistorical.org (502) 635-5083 17 APR 12 APR Our Mission To collect, preserve, and tell the significant stories of Kentucky and Ohio Valley history and culture. SATURDAY, APRIL 7 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 18 10 6:00-9:00 p.m. • Galt House Hotel, Ballroom B/C 5:00-7:30 p.m. • The Filson Historical Society APR Free keynote & reception, fee for meeting Free • Galleries and Reception open at 5:00 The 85th Annual Meeting of the Society Film Screening - Look & See: for Military History Keynote Address Wendell Berry’s Kentucky Southern Cross, North Star: The Politics of KET and The ilsonF Historical Society present a Irreconciliation and Civil War Memory in special preview screening of Look & See: Wendell Berry’s 7 APR the American Middle Border Kentucky. e than 40 works of fiction, nonfic- The author of mor Christopher Phillips tion and poetry, Kentucky writer and farmer Wendell APRIL THE THE FILSON Dr. Christopher Phillips, the John and Dorothy Hermanies Berry has often been called “a prophet for rural America,” Professor of American History, the University Distinguished giving voice to those affected by the changing landscapes Look & Professor of the Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, and and shifting values of rural America. The film See: Wendell Berry’s Kentucky, airing nationally as part of the Head of the Department of History at the University at the PBS series Independent Lens, combines observation- 6 of Cincinnati, will present the keynote address “Southern APR Cross, North Star: The Politics of Irreconciliation and Civil al scenes of farming life and interviews with farmers and War Memory in the American Middle Border.” The keynote community members with lyrical and evocative shots of address, sponsored by The Filson Historical Society, is free for the surrounding Henry County landscape. -

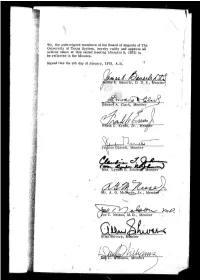

Board Minutes for January 9, 1973

1 ~6 ]. J We, the uudersigaed members of the Board of Regeats of The Uaiversity of Texas System, hereby ratify aad approve all z actions takea at this called meetiag (Jauuary 9, 1973) to be reflected in the Minutes. Signed this the 9Lh day of Jaauary, -1973, A.D. ol Je~ins Garrett, Member c • D., Member Allan( 'Shivers, M~mber ! ' /" ~ ° / ~r L ,.J J ,© Called Meeting Meeting No. 710 THE MINUTES OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM Pages I and 2 O January ~, 1973 '~ Austin, Texas J~ 1511 ' 1-09-7) ~ETING NO. 710 TUESDAY, JANUARY 9, 1973.--Pursuant to the call of the Chair on January 6, 1973 (and which call appears in the Minutes of the meeting of that date), the Board of Regents convened in a Called Session at i:00 p.m~ on January 9, 1973, in the Library of the Joe C. Thompson Conference Center, The Uni- versity of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, with the follow- ing in attendance: ,t ATTENDANCE.-- Present Absent Regent James E. Baue-~ None Regent Edward Clark Regent Frank C. Erwin, Jr. "#~?::{ill Regent Jenkins Garrett Regent (Mrs.) Lyndon Johnson Regent A. G. McNeese, Jr. );a)~ Regent Joe T. Nelson Regent Allan Shivers Regent Dan C. Williams Secretary Thedford Chancellor LeMaistre Chancellor Emeritus Ransom Deputy Chancellor Walker (On January 5, 1973, Governor Preston Smith f~amed ~the < following members of the Board of Regents of The University of Texas System: ,~ ¢.Q .n., k~f The Honorable James E. Bauerle, a dentist of San Antonio, to succeed the Honorable John Peace of San Antonio, whose term had expired. -

Genealogical Sketch Of

Genealogy and Historical Notes of Spamer and Smith Families of Maryland Appendix 2. SSeelleecctteedd CCoollllaatteerraall GGeenneeaallooggiieess ffoorr SSttrroonnggllyy CCrroossss--ccoonnnneecctteedd aanndd HHiissttoorriiccaall FFaammiillyy GGrroouuppss WWiitthhiinn tthhee EExxtteennddeedd SSmmiitthh FFaammiillyy Bayard Bache Cadwalader Carroll Chew Coursey Dallas Darnall Emory Foulke Franklin Hodge Hollyday Lloyd McCall Patrick Powel Tilghman Wright NEW EDITION Containing Additions & Corrections to June 2011 and with Illustrations Earle E. Spamer 2008 / 2011 Selected Strongly Cross-connected Collateral Genealogies of the Smith Family Note The “New Edition” includes hyperlinks embedded in boxes throughout the main genealogy. They will, when clicked in the computer’s web-browser environment, automatically redirect the user to the pertinent additions, emendations and corrections that are compiled in the separate “Additions and Corrections” section. Boxed alerts look like this: Also see Additions & Corrections [In the event that the PDF hyperlink has become inoperative or misdirects, refer to the appropriate page number as listed in the Additions and Corrections section.] The “Additions and Corrections” document is appended to the end of the main text herein and is separately paginated using Roman numerals. With a web browser on the user’s computer the hyperlinks are “live”; the user may switch back and forth between the main text and pertinent additions, corrections, or emendations. Each part of the genealogy (Parts I and II, and Appendices 1 and 2) has its own “Additions and Corrections” section. The main text of the New Edition is exactly identical to the original edition of 2008; content and pagination are not changed. The difference is the presence of the boxed “Additions and Corrections” alerts, which are superimposed on the page and do not affect text layout or pagination. -

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016

Texas Office of Lt. Governor Data Sheet As of August 25, 2016 History of Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was created by the State Constitution of 1845 and the office holder is President of the Texas Senate.1 Origins of the Office The Office of the Lt. Governor of Texas was established with statehood and the Constitution of 1845. Qualifications for Office The Council of State Governments (CSG) publishes the Book of the States (BOS) 2015. In chapter 4, Table 4.13 lists the Qualifications and Terms of Office for lieutenant governors: The Book of the States 2015 (CSG) at www.csg.org. Method of Election The National Lieutenant Governors Association (NLGA) maintains a list of the methods of electing gubernatorial successors at: http://www.nlga.us/lt-governors/office-of-lieutenant- governor/methods-of-election/. Duties and Powers A lieutenant governor may derive responsibilities one of four ways: from the Constitution, from the Legislature through statute, from the governor (thru gubernatorial appointment or executive order), thru personal initiative in office, and/or a combination of these. The principal and shared constitutional responsibility of every gubernatorial successor is to be the first official in the line of succession to the governor’s office. Succession to Office of Governor In 1853, Governor Peter Hansborough Bell resigned to take a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and Lt. Governor James W. Henderson finished the unexpired term.2 In 1861, Governor Sam Houston was removed from office and Lt. Governor Edward Clark finished the unexpired term. In 1865, Governor Pendleton Murrah left office and Lt. -

The Belo Herald Newsletter of the Col

The Belo Herald Newsletter of the Col. A. H. Belo Camp #49 And Journal of Unreconstructed Confederate Thought August 2016 This month’s meeting features a special presentation: Old Bill – Confederate Ally And Open table discussion of National Reunion The Belo Herald is an interactive newsletter. Click on the links to take you directly to additional internet resources. Col. A. H Belo Camp #49 Commander - David Hendricks st 1 Lt. Cmdr. - James Henderson nd 2 Lt. Cmdr. – Charles Heard Adjutant - Jim Echols Chaplain - Rev. Jerry Brown Editor - Nathan Bedford Forrest Contact us: WWW.BELOCAMP.COM http://www.facebook.com/BeloCamp49 Texas Division: http://www.scvtexas.org Have you paid your dues?? National: www.scv.org http://1800mydixie.com/ Come early (6:30pm), eat, fellowship with http://www.youtube.com/user/SCVORG Commander in Chief on Twitter at CiC@CiCSCV other members, learn your history! Our Next Meeting: Thursday, August 4th: 7:00 pm La Madeleine Restaurant 3906 Lemmon Ave near Oak Lawn, Dallas, TX *we meet in the private meeting room. All meetings are open to the public and guests are welcome. "Everyone should do all in his power to collect and disseminate the truth, in the hope that it may find a place in history and descend to posterity." Gen. Robert E. Lee, CSA Dec. 3rd 1865 Commander’s Report Dear BELO Compatriots, Greetings. Hope to see each of you this Thursday the 4th at la Madeleine for the dinner hour from 6:00 – 7:00p.m. and our meeting starting at 7:01p.m. The national convention is now behind us. -

Notable Southern Families Vol II

NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II (MISSING PHOTO) Page 1 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II JEFFERSON DAVIS PRESIDENT OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA Page 2 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II Copyright 1922 By ZELLA ARMSTRONG Page 3 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II COMPILED BY ZELLA ARMSTRONG Member of the Tennessee Historical Commission PRICE $4.00 PUBLISHED BY THE LOOKOUT PUBLISHING CO. CHATTANOOGA, TENN. Page 4 of 327 NOTABLE SOUTHERN FAMILIES VOLUME II Table of Contents FOREWORD....................................................................10 BEAN........................................................................11 BOONE.......................................................................19 I GEORGE BOONE...........................................................20 II SARAH BOONE...........................................................20 III SQUIRE BOONE.........................................................20 VI DANIEL BOONE..........................................................21 BORDEN......................................................................23 COAT OF ARMS.............................................................29 BRIAN.......................................................................30 THIRD GENERATION.........................................................31 WILLIAM BRYAN AND MARY BOONE BRYAN.......................................33 WILLIAM BRYAN LINE.......................................................36 FIRST GENERATION -

2020-2022 Law School Catalog

The University of at Austin Law School Catalog 2020-2022 Table of Contents Examinations ..................................................................................... 11 Grades and Minimum Performance Standards ............................... 11 Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 Registration on the Pass/Fail Basis ......................................... 11 Board of Regents ................................................................................ 2 Minimum Performance Standards ............................................ 11 Officers of the Administration ............................................................ 2 Honors ............................................................................................... 12 General Information ................................................................................... 3 Graduation ......................................................................................... 12 Mission of the School of Law ............................................................ 3 Degrees ..................................................................................................... 14 Statement on Equal Educational Opportunity ................................... 3 Doctor of Jurisprudence ................................................................... 14 Facilities .............................................................................................. 3 Curriculum ................................................................................. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse.