Sub-Surface Archaeological Investigation of Stages 2-4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLIENT PROOF Leonards Key No: 97933 Section/Sort: Public Notices Account Exec: Tracy Client Rev

p 02 9698 5266 f 02 9699 2433 CLIENT PROOF Leonards Key No: 97933 Section/Sort: Public Notices Account Exec: Tracy Client Rev. No: 1 Publication: Milton Ulladulla Times Ad Size (HxW): 30cm x 6 columns Operator Name: Insertion Date: Wed 26/8/20 Size (HxW): 30 x 19.8cm Proofreader Name: Please proof your advertisement thoroughly and advise us of your approval as soon as possible via eziSuite, email or fax. Client Signature: The final responsibility for the accuracy of your advertisement content and placement details rests with you, our valuedclient. Leonards will not be held responsible for any errors or for liability under the Trade Practices Act. Date/Time: white primary Notices white business as prescribed by Section 4.15 of the Act and DA20/1302 32 Seaspray St, NARRAWALLEE Public Notices particularly in relation to the provisions of Residential. Single new dwelling. Shoalhaven Local Environmental Plan and Proposal to Lease Lot 173 DP 755967 corp blue primaryDA20/1371 142 Matron Porter Dr, NARRAWALLEE Development Control Plan. Residential. Alterations and additions. 158 Green Street, Ulladulla corp blue business JUNE – Southern Area CD20/1325 16 Amaroo Dr, NARRAWALLEE In accordance with the requirements of the Local DA19/1912 65A Murramarang Rd, BAWLEY POINT Residential. Single new dwelling. Government Act 1993, Council hereby gives twenty Residential. New second occupancy. CD20/1312 28 Hastings Pde, SUSSEX INLET eight (28) days’ notice of its intention to lease DA20/1286 21 Oriole St, BAWLEY POINT Residential. Single new dwelling. community land described as Lot 173 DP 755967, corp black primary Residential. Alterations and additions. -

Agenda of Strategy and Assets Committee

Meeting Agenda Strategy and Assets Committee Meeting Date: Tuesday, 18 May, 2021 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Membership (Quorum - 5) Clr John Wells - Chairperson Clr Bob Proudfoot All Councillors Chief Executive Officer or nominee Please note: The proceedings of this meeting (including presentations, deputations and debate) will be webcast and may be recorded and broadcast under the provisions of the Code of Meeting Practice. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies / Leave of Absence 2. Confirmation of Minutes • Strategy and Assets Committee - 13 April 2021 ........................................................ 1 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Mayoral Minute 5. Deputations and Presentations 6. Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice SA21.73 Notice of Motion - Creating a Dementia Friendly Shoalhaven ................... 23 SA21.74 Notice of Motion - Reconstruction and Sealing Hames Rd Parma ............. 25 SA21.75 Notice of Motion - Cost of Refurbishment of the Mayoral Office ................ 26 SA21.76 Notice of Motion - Madeira Vine Infestation Transport For NSW Land Berry ......................................................................................................... 27 SA21.77 Notice of Motion - Possible RAAF World War 2 Memorial ......................... 28 7. Reports CEO SA21.78 Application for Community -

Wandrawandian Siltstone, New South Wales: Record of Glaciation?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences of 2007 Lithostratigraphy of the late Early Permian (Kungurian) Wandrawandian Siltstone, New South Wales: Record of glaciation? S. G. Thomas Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Christopher R. Fielding University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Tracy D. Frank University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Thomas, S. G.; Fielding, Christopher R.; and Frank, Tracy D., "Lithostratigraphy of the late Early Permian (Kungurian) Wandrawandian Siltstone, New South Wales: Record of glaciation?" (2007). Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 105. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub/105 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 54 (2007), pp. 1057–1071; doi: 10.1080/08120090701615717 Copyright © 2007 Geological Society of Australia; published by Taylor & Francis. Used by permission. Submitted March 22, 2006; accepted June 21, 2007. Lithostratigraphy of the late Early Permian (Kungurian) Wandrawandian -

No. 52 Shoalhaven City Council

Submission No 52 INQUIRY INTO CLOSURE OF THE CRONULLA FISHERIES RESEARCH CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE Organisation: Shoalhaven City Council Date received: 1/08/2012 SUBMISSION BY SHOALHAVEN CITY COUNCIL TO SELECT COMMITTEE ON CRONULLA FISHERIES CLOSURE Council wishes to make a submission to the Select Committee specifically on the following points: (c) the costs and benefits of the decision to close the Centre and relocate its functions to other locations, (e) any advice received by the Minister on the ability to replicate the Cronulla facilities at other locations, including potential problems and other implications of the other locations, (g) the impacts of service delivery to stakeholders (h) the impact on staff and their families of the closure and the relocation Submission by Shoalhaven Council to Inquiry into Relocation of Cronulla Fisheries Page 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION Council contends that relocating part of the Cronulla operations of NSW Fisheries to Nowra makes sound economic and social sense. Several major government functions, both State and Federal have made the transfer to Nowra over the last 10- 15 years resulting in over 500 additional employment positions within the Shoalhaven labour force. With in excess of 38,000 persons within the Shoalhaven labour force the area still experiences an unemployment rate of around 9.7% caused by continual population growth and the structural adjustment of new residents into the local workforce. Families are attracted to the area because of lower housing and living costs which are available within the Shoalhaven area. This growth in population and the consequential growth in labour force, requires a continual growth in employment opportunities to be created. -

Agenda of Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group

Shoalhaven City Council Contents Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group Meeting Date: Monday, 24 June, 2019 Location: Jervis Bay Rooms, City Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Please note: Council’s Code of Meeting Practice permits the electronic recording and broadcast of the proceedings of meetings of the Council which are open to the public. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies 2. Confirmation of Minutes Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group - 6 May 2019 ................................................... 1 3. Reports TA19.23 Tourism Manager's Report ........................................................................... 8 TA19.24 Destination Marketing ................................................................................. 11 TA19.25 Events and Investment ............................................................................... 25 TA19.26 Visitor Services Update April 2019 ............................................................. 37 TA19.27 River Festival Committee Update ............................................................... 40 TA19.28 Sports Board Update .................................................................................. 42 TA19.29 Councillor Updates ..................................................................................... 43 TA19.30 Industry Feedback ..................................................................................... -

Check out Main Road 92

Canberra to Bungendore Oallen Ford Road ends at a T-intersection with Nerriga Road, turn left towards Nerriga. Nerriga is a small village on the edge From Canberra, take the Kings Highway/National Route 52 of Morton National Park. The iconic Nerriga Hotel is a great to Bungendore. Stop here for a coffee and stroll through the spot for lunch or refreshements, with live music on the last Wood Works Gallery or continue on towards Goulburn and Sunday of each month. Tarago. Nerriga to Nowra Bungendore to Tarago Continue along Nerriga Road following the signs to Nowra. At Take Tarago Road out of Bungendore, and continue on, the Endrick River crossing the road becomes Braidwood Road crossing the railway near the Tarago village centre. A popular and winds its way past beautiful sandstone cliffs at Bulee Gap. stopping point is Tarago’s Loaded Dog Hotel, named after It is still possible in places to view the original road built by the humerous short story by Australian writer Henry Lawson convicts in 1841. Further along at Sassafrass, chestnuts may be and famous as a ‘safe house’ for bushrangers such as Frank for picking and sale in season around March/April. Gardiner and Ben Hall in the 1860s. For a spectacular view, turn-off to Tianjara Falls lookout. Tarago to Nerriga As you approach the Defence base, HMAS Albatross, turn left The road out of Tarago (Lumley Rd) crosses the Braidwood– onto Albatross Road, then along Kinghorne Street to arrive in Goulburn Road and continues on through a line of pines along Nowra township. -

Shoalhaven EMPLAN Emergency Management Plan 2018 Shoalhaven Local Emergency Management Plan

Shoalhaven EMPLAN Emergency Management Plan 2018 Shoalhaven Local Emergency Management Plan Authorisation The Shoalhaven Local Emergency Management Plan (EMPLAN) has been prepared by the Shoalhaven Local Emergency Management Committee in compliance with the State Emergency & Rescue Management Act 1989, Section 29 (1) APPROVED ……………………………………………………… Chair Shoalhaven Local Emergency Management Committee Dated: ENDORSED ……………………………………………………… Chair Illawarra South Coast Regional Emergency Management Committee Dated: Page 1 of 38 Shoalhaven Local Emergency Management Plan Contents Authorisation ..................................................................................................................... 1 Contents ............................................................................................................................ 2 Document Control ............................................................................................................. 3 Distribution ........................................................................................................................ 4 Abbreviations .................................................................................................................... 6 Part 1 - Administration .......................................................................................................... 8 Authority ............................................................................................................................ 8 Purpose ............................................................................................................................ -

Vincentia 4,099 SQM 21 $57.2M CAR SPACES MAJORS SPECIALTY SALES $PSM 171 COLES $6,642*

Centre Information GLA SPECIALTY NO MAT SALES Vincentia 4,099 SQM 21 $57.2M CAR SPACES MAJORS SPECIALTY SALES $PSM 171 COLES $6,642* Information is accurate as at 31 December 2015. Specialty number includes kiosks and shops. Does not include ATMs. *This number is based on annualised sales. Key Major Mini-Major Specialty 35 38 37 36 33-34 30-31 32 Vincentia Shopping Centre is a The property is situated in Vincentia, single level, open air neighbourhood a developing residential and tourist ool Road shopping centre. township on the south coast of NSW. cellent Street Ex The centre is anchored by a strong The W performing Coles and 21 specialty stores. M01 27 11 26 21 20 19 18 17 15 14 13 12 24 Burton Street Mall CENTRE LEASING Stockland Vincentia, 5 Burton Street, Vincentia NSW 2540 P 02 9035 2080 www.stockland.com.au E [email protected] NM NSW Trade Area Demographic MAIN TRADE AREA OF Characteristics Primary Sector Secondary Sector Main TA Average Vincentia Shopping Centre services a main Income Levels trade area of 24,284 people with 19,310 located 24,284 Average Per Capita Income $19,164 $17,413 $18,798 $22,878 Per Capita Income Variation -16.2% -23.9% -17.8% n.a. in the primary trade area. The average income Average Household Income $45,228 $37,668 $43,536 $56,695 is $43,536 with an average of 44.4 years. Household Income Variation -20.2% -33.6% -23.2% n.a. Home ownership is at 75.7%, higher than Average Household Size 2.4 2.2 2.3 2.5 HIGH PROPORTION OF SENIORS AT the non-metro NSW average of 71.4%. -

Asset Management Plan Bus Shelters

Asset Management Plan Bus Shelters Policy Number: POL07/75 Adopted: 29 April 2003 Minute Number: MIN03.468 File: 25442 Produced By: Strategic Planning Group Review Date: 29/04/2004 For more information contact the Strategic Planning Group Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra • Telephone (02) 4429 3111 • Fax (02) 4422 1816 • PO Box 42 Nowra 2541 Southern District Office – Deering Street, Ulladulla • Telephone (02) 4429 8999 • Fax (02) 4429 8939 • PO Box 737 Ulladulla [email protected] • www.shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au CONTENTS 1. PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ...........................................................................................................1 2. ASSET DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................................1 3. ASSET EXTENT AND CONDITION ..........................................................................................1 4. CAPITAL WORKS STRATEGIES..............................................................................................2 4.1. Provision of New Shelters.....................................................................................................2 4.2. Replacement Strategy ...........................................................................................................2 4.3. Enhancement Strategies ........................................................................................................3 5. FUNDING NEED SUMMARY AND LEVELS OF SERVICE..................................................3 5.1. Summary -

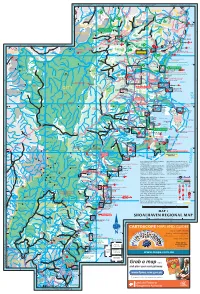

Shaolhaven Region

For adjoining map see Cartoscope's For adjoining map see Cartoscope's TO ALBION B Capital Country Tourist Map TO MOSS VALE 10km TO ROBERTSON 6km C Illawarra Region Tourist Map D PARK 5km TO SHELLHARBOUR 5km MOSS RD RD 150º30'E 150º20'E 150º40'E 150º50'E O Fitzroy Creek O RD R E Bundanoon Falls KIAMA B TD 15 Carrington Reservoir M AM Creek 79 in J Minnamurra Falls nam Dam urr Minnamurra a VALE Belmore River RIVER Falls Y Falls A 31km Creek Jamberoo MERYLA TD 8 BUDDEROO 9 W MERYLA Fitzroy MYRA H G Falls y I r n H o r o SF 907 a n Gerringong TD 9 34º40'S a g TRACK d n Falls n RD e u r NATIONAL B r Upper TO MARULAN Kiama River a Kangaroo B Valley BARRENCOUNCIL WINGECARRIBEE VALE Barrengarry PARK GROUNDS Saddleback TOURIST DRIVE Mt 7 8 Hampden Bridge: Mt 14 Built 1898, Saddleback 1 RD NR Lookout 1 oldest suspension BUDDEROO Foxground Mt Carrialoo bridge in Australia COUNCIL Mt CK Moollatoo Kangaroo Valley Creek Mt Pleasant Power Station Lookout Bendeela B Pondage For detail see ro WOODHILL ge Wattamolla RD Bendeela Map 10 rs MTN Werri Beach Bendeela Campground RD 3 LA Proposed RD OL RODWAY PRINCES Power TAM Upgrade Station Kangaroo WAT NR RD KAN 18 Gerringong Valley GA DR 13 RO BLACK For adjoining map see Cartoscope's 15 O ASH TD 7 A TO MARULAN 8km Capital Country Tourist Map Broughton NR 11 MT DEVILS CAOURA VALLEY GLEN NR RD Village Mt Skanzi 79 DAM Gerroa RD 9 For detail Berry Ck Marulan TALLOWA CAMBERWARRA RAILWAY 150º00'E 150º10'E Mt Phillips RANGE NR TD 7/8 see Map 15 Quarry FIRE Tallowa Dam Steep and very windy road, BEACH RD Black Head -

Agenda of Ordinary Meeting

Shoalhaven City Council Ordinary Meeting Meeting Date: Monday, 25 January, 2021 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Building, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Membership (Quorum - 7) All Councillors Please note: The proceedings of this meeting (including presentations, deputations and debate) will be webcast and may be recorded and broadcast under the provisions of the Code of Meeting Practice. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Acknowledgement of Traditional Custodians 2. Opening Prayer 3. Australian National Anthem 4. Apologies / Leave of Absence 5. Confirmation of Minutes • Ordinary Meeting - 15 December 2020 6. Declarations of Interest 7. Presentation of Petitions 8. Mayoral Minute 9. Deputations and Presentations 10. Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice CL21.1 Notice of Motion - SNAG - Swan Lake Cudmirrah Bridge ............................ 1 CL21.2 Notice of Motion - Upgrade of Lighting - Milton Ulladulla Tennis Facility ......................................................................................................... 2 CL21.3 Notice of Motion - Thurgate Oval – “Bomo” Dog Park ................................. 3 CL21.4 Notice of Motion - West Culburra Proposed Mixed Use Concept Plan ......... 4 CL21.5 Notice of Motion - DA Tracker - Current Issues ........................................... 5 CL21.6 Notice of Motion - Nowra By-pass .............................................................. -

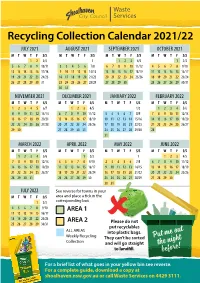

For a Brief List of What Goes in Your Yellow Bin See Reverse. for a Complete Guide, Download a Copy at Shoalhaven.Nsw.Gov.Au Or Call Waste Services on 4429 3111

For a brief list of what goes in your yellow bin see reverse. For a complete guide, download a copy at shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au or call Waste Services on 4429 3111. Calendar pick-up dates are colour coded to correspond with your area. AREA 1 Hyams Beach AREA 2 Mollymook Basin View Illaroo Back Forest Morton Bawley Point Jaspers Brush Bamarang Mundamia Beaumont Kings Point Bangalee Narrawallee Bellawongarah Kioloa Barrengarry North Nowra Berry Lake Tabourie Bendalong Nowra Bewong Meroo Meadow* Berrara Nowra Hill* Bomaderry Milton* Berringer Lake Numbaa Broughton Mollymook Beach* Bolong Pointer Mountain Budgong Myola Brundee* Pyree* Bundewallah Old Erowal Bay Cambewarra Sanctuary Point Burrill Lake Orient Point Comerong Island Shoalhaven Heads Callala Bay Parma Conjola South Nowra Callala Beach Termeil* Conjola Park St Georges Basin Croobyar* Tomerong* Coolangatta Sussex Inlet Culburra Beach Vincentia Cudmirrah Swanhaven Currarong Wandandian Cunjurong Point Tapitallee* Depot Beach Watersleigh Far Meadow* Terara Dolphin Point Wattamolla Fishermans Paradise Ulladulla Durras North Woodhill Jerrawangala West Nowra East Lynne Woollamia Kangaroo Valley Wollumboola Erowal Bay Worrigee* Lake Conjola Woodburn Falls Creek Worrowing Heights Little Forest Woodstock Greenwell Point Wrights Beach Longreach Yatte Yattah Huskisson Yerriyong Manyana * Please note: A small number of properties in these towns have their recycling collected on the alternate week indicated on this calendar schedule. Please go to shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au/my-area and search your address or call Waste Services on 4429 3111. What goes in your yellow bin Get the Guide! • Glass Bottles and Jars Download a copy at • Paper and Flattened Cardboard shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au • Milk and Juice Containers or call Waste Services • Rigid Plastic Containers (eg detergent, sauce, on 4429 3111.