(2016). Easy Access, Easy Wins? Advocating for Inclusive Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peasant Resilience and Stakes in Crop Cultivation Within an Unstable Bio-Physical Milieu: the Case of Bui Division, North West Region, Cameroon

American Journal of Environmental Protection 2021; 10(2): 37-52 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajep doi: 10.11648/j.ajep.20211002.11 ISSN: 2328-5680 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5699 (Online) Peasant Resilience and Stakes in Crop Cultivation Within an Unstable Bio-Physical Milieu: The Case of Bui Division, North West Region, Cameroon Godwill Tobouah Nyanchi 1, * , Mbanga Lawrence Akei 2, Frankline Nghobuoche 1, Tassah Ivo Tawe 1, Nkiene Valery Antu 1, Mkong Unity Ghekendeh 3 1Department of Geography, University of Yaoundé, Yaoundé, Cameroon 2Department of Geography and Planning, University of Bamenda, Bamenda, Cameroon 3Department of Sociology, University of Yaoundé, Yaoundé, Cameroon Email address: *Corresponding author To cite this article: Godwill Tobouah Nyanchi, Mbanga Lawrence Akei, Frankline Nghobuoche, Tassah Ivo Tawe, Nkiene Valery Antu, Mkong Unity Ghekendeh. Peasant Resilience and Stakes in Crop Cultivation Within an Unstable Bio-Physical Milieu: The Case of Bui Division, North West Region, Cameroon. American Journal of Environmental Protection. Vol. 10, No. 2, 2021, pp. 37-52. doi: 10.11648/j.ajep.20211002.11 Received : August 4, 2020; Accepted : May 7, 2021; Published : May 20, 2021 Abstract: Prospects of food crop cultivation and supply center on peasant resilience and their adaptability to the surrounding bio-physical milieu. Farmers’ predisposition to the numerous challenges within their biophysical context makes them resilient and thoughtful in strengthening their skills. The soils, relief, climate and vegetation of Bui Division heighten farmers’ resilience for harmonious, flourishing and innovative techniques to hold the farmers spellbound in their daily farm operations. In addition, vegetables are cultivated abundantly in wetland areas during the dry season. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

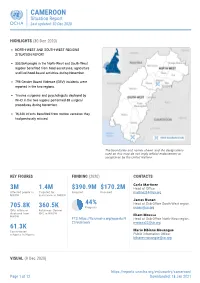

Situation Report Last Updated: 30 Dec 2020

CAMEROON Situation Report Last updated: 30 Dec 2020 HIGHLIGHTS (30 Dec 2020) NORTH-WEST AND SOUTH-WEST REGIONS SITUATION REPORT 333,864 people in the North-West and South-West regions benefited from food assistance, agriculture and livelihood-based activities during November. 798 Gender Based Violence (GBV) incidents were reported in the two regions. Trauma surgeons and psychologists deployed by WHO in the two regions performed 69 surgical procedures during November. 16,448 infants benefited from routine vaccines they had previously missed. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (2020) CONTACTS Carla Martinez 3M 1.4M $390.9M $170.2M Head of Office Affected people in Targeted for Required Received [email protected] NWSW assistance in NWSW ! j e James Nunan r , y d r r n 44% Head of Sub-Office South-West region o A 705.8K 360.5K S Progress [email protected] IDPs within or Returnees (former displaced from IDP) in NWSW NWSW Ilham Moussa FTS: https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/9 Head of Sub-Office North-West region 27/summary [email protected] 61.3K Cameroonian Marie Bibiane Mouangue refugees in Nigeria Public information Officer [email protected] VISUAL (9 Dec 2020) https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/cameroon/ Page 1 of 12 Downloaded: 18 Jan 2021 CAMEROON Situation Report Last updated: 30 Dec 2020 Map of IDP, Returnees and Refugees from the North-West and South-West Regions of Cameroon Source: OCHA, UNHCR, IOM, CHOI, Partners The boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

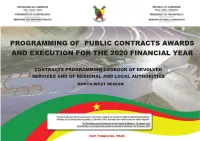

Programming of Public Contracts Awards and Execution for the 2020

PROGRAMMING OF PUBLIC CONTRACTS AWARDS AND EXECUTION FOR THE 2020 FINANCIAL YEAR CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING LOGBOOK OF DEVOLVED SERVICES AND OF REGIONAL AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES NORTH-WEST REGION 2021 FINANCIAL YEAR SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of No Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts No. page contracts REGIONAL 1 External Services 9 514 047 000 3 6 Bamenda City Council 13 1 391 000 000 4 Boyo Division 9 Belo Council 8 233 156 555 5 10 Fonfuka Council 10 186 760 000 6 11 Fundong Council 8 203 050 000 7 12 Njinikom Council 10 267 760 000 8 TOTAL 36 890 726 555 Bui Division 13 External Services 3 151 484 000 9 14 Elak-Oku Council 6 176 050 000 9 15 Jakiri Council 10 266 600 000 10 16 Kumbo Council 5 188 050 000 11 17 Mbiame Council 6 189 050 000 11 18 Nkor Noni Council 9 253 710 000 12 19 Nkum Council 8 295 760 002 13 TOTAL 47 1 520 704 002 Donga Mantung Division 20 External Services 1 22 000 000 14 21 Ako Council 8 205 128 308 14 22 Misaje Council 9 226 710 000 15 23 Ndu Council 6 191 999 998 16 24 Nkambe Council 14 257 100 000 16 25 Nwa Council 10 274 745 452 18 TOTAL 48 1 177 683 758 Menchum Division 27 Furu Awa Council 4 221 710 000 19 28 Benakuma Council 9 258 760 000 19 29 Wum Council 7 205 735 000 20 30 Zhoa Council 5 184 550 000 21 TOTAL 25 870 755 000 MINMAP/Public Contracts Programming and Monitoring Division Page 1 of 37 SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of No Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts No. -

Dynamics of Indigenous Socialization Strategies and Emotion Regulation Adjustment Among Nso Early Adolescents, North West Region of Cameroon

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 3, Issue 8, August 2016, PP 86-124 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0308009 www.arcjournals.org Dynamics of Indigenous Socialization Strategies and Emotion Regulation Adjustment among Nso Early Adolescents, North West Region of Cameroon Therese Mungah Shalo Tchombe Ph.D. Emeritus Professor of Applied Cognitive Developmental Psychology, UNESCO Chair for Special Needs Education, University of Buea, Cameroon P.O. Box 63 Director, Centre for Research in Child and Family Development & Education (CRCFDE) P.O. Box 901, Limbe, Cameroon Tani Emmanuel Lukong, Ph.D. Lecturer, University of Buea, Founder, “Foundation of ScientificResearch, Community Based Rehabilitation and Advocacy on Inclusive Education” (FORCAIE-CAMEROON) [email protected] Abstract: Cultural values vary across cultures and social ecologies. Cultural communities define and endorse human abilities they perceive to give expression to their core values. This study aimed to examine the interaction among specific indigenous strategies of socialization such as indigenous proverbs, and indigenous games) within an eco-cultural setting which dictate a more cultural specific dimension on emotion regulation adjustment with keen attention on social competence skills and problem solving skills through an indigenized conceptual model of the Nso people of Cameroon. The study had three objectives; the study had a sample of 272. Results indicate that, proverbs -

CAMEROON, FIRST HALFYEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 19 December 2019

CAMEROON, FIRST HALFYEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 19 December 2019 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 14 December 2019; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, FIRST HALFYEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 19 DECEMBER 2019 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 206 115 298 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 117 74 417 Development of conflict incidents from June 2017 to June 2019 2 Strategic developments 47 0 0 Protests 23 0 0 Methodology 3 Explosions / Remote 10 10 17 Conflict incidents per province 4 violence Riots 5 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 408 200 733 Disclaimer 5 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 14 December 2019). Development of conflict incidents from June 2017 to June 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 14 December 2019). 2 CAMEROON, FIRST HALFYEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 19 DECEMBER 2019 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Cameroon-North West/South West Regions:Wash

CAMEROON-NORTH WEST/SOUTH WEST REGIONS: WASH Operational Presence (1-30 Nov. 2020) DONGA-MANTUNG MENCHUM Fungom Ako COMINSUD-NRC H4BF-Global Aid for Africa Nkambe North-West South-West GCR Menchum Donga-Mantung BUI Kumbo MOMO CBC-NRC, SUDAHSER Mbengwi Jakiri 9 Local NGOs NRC North-West Boyo CBC-NRC INGOs Nkum 3 H4BF-Global Aid for Africa Reported in November. Bui MANYU Mamfe Momo Mezam AFRINET-UNICEF Ngo-Ketunjia Eyumodjock Manyu AFRINET-UNICEF MEZAM Bamenda 1 LEBIALEM SUDAHSER-STREETCHILD, IRC-GFFO NDIAN Lebialem Ekondo Titi Fontem Bamenda 2 IRC-LDS-GFFO AFRINET-UNICEF GCR, SUDAHSER-STREETCHILD, IRC-GFFO REACHOUT, SUDAHSER Wabane Bamenda 3 Kombo Itindi IRC-GFFO IRC-GFFO, SUDAHSER-STREETCHILD EPDA-UNICEF, IRC-GFFO Santa NRC South-West KUPE -MANENGUBA Kupe-Manenguba Bangem MEME AFRINET-UNICEF Konye Nguti IRC-GFFO AFRINET-UNICEF Kumba 1 Ndian Tombel IRC-LDS, AFRINET- UNICEF FAKO Buea AFRINET-UNICEF Kumba 2 Meme NRC, IRC-LDS,GFFO NRC Muyuka Kumba 3 NRC, FORUDEF, IRC-GFFO IRC-LDS Tiko Implementing Partner Mbonge NRC 0 IRC-GFFO, AFRINET- UNICEF West Coast 1 AFRINET-UNICEF, NRC 2 - 33 Fako Is your data missing from this Map? Division boundary If yes please share your 5W matrix with Stancelous Mverechena on [email protected] Sub-division boundary Download 5W template here: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/op%C3%A9rati Lead/Donor agency ons/cameroon/document/nwsw-wash-5w-template ´ Map Data Source(s): NW/SW WASH Cluster Partners Date Updated: 15 November 2020 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.. -

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 162 92 263 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 111 50 316 Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 2 Strategic developments 39 0 0 Protests 23 1 1 Methodology 3 Riots 14 4 5 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 10 7 22 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 359 154 607 Disclaimer 5 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

OXIDATION PHENOMENON of FERROUS to FERRIC IRON in WATER SOURCES of BUI DIVISION, NORTH WEST REGION of CAMEROON (Case Study of Mbiame Water Catchment)

ISSN 2394-9716 International Journal of Novel Research in Interdisciplinary Studies Vol. 6, Issue 2, pp: (10-15), Month: March - April 2019, Available at: www.noveltyjournals.com OXIDATION PHENOMENON OF FERROUS TO FERRIC IRON IN WATER SOURCES OF BUI DIVISION, NORTH WEST REGION OF CAMEROON (Case study of Mbiame water catchment) 1Fondzenyuy Vitalis Fonfo, 2Kengni Lucas 1,2 University of Dschang, Faculty of Science. Department of Earth Sciences, P.O Box 67 Dschang. Abstract: Oxidation is accompanied by addition of oxygen or a loss of electron by a species. Aluminium and iron were dominant heavy metals in Bui water bodies. Iron has two oxidation states (Fe2+ and Fe3+). Fe3+ is more stable, accounted for by the stability of electrons in its atomic orbitals, whereas the unstable state converts to the more stable form. Oxidation was observed in Bui water sources, very pronounced at Mbiame catchment in Mbven subdivision. The consequence of this oxidation phenomenon was the predominanance of a reddish–brownish colouration. This was glaring as water samples changed colour from greenish to reddish on exposure in a beaker few minutes after sampling indicating intense aerial oxidation. This phenomenon is characteristic of transition metals with variable oxidation states and produce coloured solutions. The process expressed in this article does not compromise water quality. The concentrations Al and Fe remained within suitable limits for water consumption, stipulated in norms such as the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2004, 2008). A paradigm shift is made from the assertion wherein coloured water was generally considered unsuitable for human consumption particularly drinking. Keywords: water colouration, ferrous and ferric iron, transition metals. -

Changing Legislation and Neglect of Local Government's Role in The

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume V, Issue I, January 2021|ISSN 2454-6186 Changing Legislation and Neglect of Local Government‟s Role in the Management of Farmer- Grazier Conflicts as Rational for the Degeneration of Crises in the Bamenda Grasslands of Cameroon Protus Mbeum Tem (PhD) The University of Bamenda, Cameroon Abstract: Farmer-grazier conflicts remain one of the greatest has greatly contributed to the entrenchment of these crises in factors that have impeded peaceful coexistence between farmers the region. The indigenes believe that they owned the land and and graziers in the Bamenda Grasslands of Cameroon. In spite see the Fulani as foreigners without any right to ownership of of attempts made by the colonial and post-colonial governments this scarce resource (Ami-Nyo and Lang, 2016; Ngalim in arresting the problem, the hitch has persisted over the years. 2015). Though the re-occurrence of these conflicts has been attributed to corruption perpetuated by those involved in the management Such a view has been supported by Nzeh (2015) who holds of these crises, the paper argues that the termination of local that “by their culture, tradition and occupation, they remained government’s role in the management of these conflicts in 1978 an itinerant race who neither owned lands nor any permanent instead intensified skirmishes. Drawing allusion from colonial abode. In fact they cared less about ownership because they legislation where local governments had the final authority, outbursts was uncommon. However, the granting of authority to are always on the move”. He further opines that they were central government officials after independence instead fanned ready to settle with their cattle wherever tsetse flies were these conflicts and greatly worked against its mitigation. -

Cartography of the War in Southern Cameroons Ambazonia

Failed Decolonization of Africa and the Rise of New States: Cartography of the War in Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Roland Ngwatung Afungang* pp. 53-75 Introduction From the 1870s to the 1900s, many European countries invaded Africa and colonized almost the entire continent except Liberia and Ethiopia. African kingdoms at the time fought deadly battles with the imperialists but failed to stop them. The invaders went on and occupied Africa, an occupation that lasted up to the 1980s. After World War II, the United Nations (UN) resolution 1514 of 14 December 1960 (UN Resolution 1415 (1960), accessed on 13 Feb. 2019) obliged the colonial powers to grant independence to colonized peoples and between 1957 and 1970, over 90 percent of African countries got independence. However, decolonization was not complete as some colonial powers refused to adhere to all the provisions of the above UN resolution. For example, the Portuguese refused to grant independence to its African colonies (e.g. Angola and Mozambique). The French on their part granted conditional independence to their colonies by maintaining significant ties and control through the France-Afrique accord (an agreement signed between France and its colonies in Africa). The France-Afrique accord led to the creation of the Franc CFA, a currency produced and managed by the French treasury and used by fourteen African countries (African Business, 2012). CFA is the acronym for “Communauté Financière Africaine” which in English stands for “African Financial Community”. Other colonial powers violated the resolution by granting independence to their colonies under a merger agreement. This was the case of former British Southern Cameroons and Republic of Cameroon, South Sudan and Republic of Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia, Senegal and Gambia (Senegambia Confederation, 1982-1989).