Enterprise Bargaining and the Accord

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 21/10/2016 “We Will End up Being a Third Rate Economy …A Banana Republic”: How Behavioural Economics Can Improve Macroec

1 Australian Economic Review Forthcoming 21/10/2016 “We will end up being a third rate economy …a banana republic”: How behavioural economics can improve macroeconomic outcomes Ian M McDonald University of Melbourne Abstract To address the economic problems facing Australia in 1986 required wage restraint which required in turn overcoming loss aversion by workers with respect to their wages. The Prices and Incomes Accord was able to do this. Attempts to address Australia’s current economic problems are stymied by tax resistance. Addressing tax resistance requires overcoming loss aversion by voters with respect to their post-tax incomes. The success of the Accord suggests that Accord-type policies could reduce tax resistance by broadening people’s perspective beyond their post-tax incomes to the broader spread of benefits for them and others. Short abstract The Prices and Incomes Accord overcame loss aversion and delivered wage restraint. Can Accord-like policies overcome loss aversion and deliver the increases in taxation that will address Australia’s current economic challenges? 2 “We will end up being a third rate economy …a banana republic”: How behavioural economics can improve macroeconomic outcomes 1 Ian M McDonald University of Melbourne 30 years ago, faced with a large fall in the terms of trade occurring in a situation of high unemployment, high inflation, a high government budget deficit and a high current account deficit, Paul Keating, the Treasurer of Australia, warned the public that Australia faced the prospect of becoming a banana republic.2 Keating's iconic statement arose in the context of an elaborate economic program, called The Prices and Incomes Accord, aimed at improving Australia's economic performance. -

The Origins of the Australian System of Superannuation

PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Easson First name: Mary Other namejs: Louise Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: M.Phil School: Australian School of Business Centre for Pensions and Superannuation Title: Present at the Creation: The Origins of the Australian System of Superannuation Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE} The thesis explores the origins and development of the Australian system of superannuation, from 1983 to the mid-1990s, during the terms of the Hawke and Keating Labor Governments, and the Accords between those governments and the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), on behalf of the Australian union movement. Prior to 1983, access to superannuation was largely confined to male managerial and professional employees and was further limited in terms of eligibility, vesting and portability. In the 1970s unions began to exploit limited power in particular enterprises and industries to pursue superannuation as deferred income. The three tier Australian system evolves from this start: (i) mandatory contributions under legislation; (ii) employee supplements to retirement savings; and, (iii) a social security safety net, the universal age pension entitlement. Relentlessly pursued by the unions, generalled by ACTU Secretary Bill Kelty, from Accord Mark J in 1983, and its subsequent iterations, superannuation became an industrial right. lt may never have occurred but for the leadership of Prime Minister Bob Hawke and particularly his Treasurer, later Prime Minister, Paul Keating. The circumstances of the origin of Australia's system of compulsory superannuation were unique. A question explored and answered in the thesis is whether its origins and development were deliberate or largely accidental. -

SOCIAL DEMOCRACY and the "FAILURE" of the ACCORD Tom

SOCIAL DEMOCRACY AND THE "FAILURE" OF THE ACCORD Tom Bramble School of Business University of Queensland Brisbane Q 4072 AUSTRALIA [email protected] Published in K. Wilson, J. Bradford, and M. Fitzpatrick (eds) (2000): Australia in Accord: An Evaluation of the Prices and Incomes Accord in the Hawke-Keating Years, South Pacific Publishing, Melbourne, pp.243-64. 2 SOCIAL DEMOCRACY AND THE "FAILURE" OF THE ACCORD1 INTRODUCTION Most sections of the industrial relations academic community (broadly defined) started with favourable impressions of the ALP-ACTU Prices and Incomes Accord. Amongst its keenest and most articulate supporters were academics and unionists writing from an explicitly social democratic perspective. Frequently drawing on the German and Scandinavian experiences, writers such as Hughes (1981), Hartnett (1981), Higgins (1978, 1980, 1985), Stilwell (1982), Burford (1983), Ogden (1984), Mathews (1986), and Clegg et al (1986) argued that the Accord would enable the union movement to break out of its labourist straitjacket to encompass broader political concerns and to develop a social role well beyond the ranks of organised labour.2 Similarly it was the left unions such as the Building Workers Industrial Union (BWIU) and Metal Workers Union (AMWU) who were most successful in developing an ideological underpinning for the Accord within the labour movement and who were most influential in winning support for it amongst workers who had the capacity to render it impotent. Opponents of the Accord at the time were almost entirely limited to Left organisations outside the Labor and Communist Parties (below) and a minority of right-wing commentators (for example Terry McCrann in The Age), the former on the basis that it represented an attack on wages and workers' rights under the rubric of social justice, the latter that it did not attack unions hard enough. -

The Ghost of National Superannuation FINAL

The Ghost of National Superannuation Emily Millane LLB, BA Arts (Hons) University of Melbourne Crawford School of Public Policy College of Asia and the Pacific Australian National University November 2019 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University © Copyright by Emily Millane, 2019 All Rights Reserved 1 Statement of originality This study has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the thesis. Emily Millane 2 ABSTRACT The thesis uses the case study of Australian superannuation to examine the conditions for systemic policy change. It tells the history of a modern reform. Long-running debates about superannuation policy have led to the system that Australians know today. A narrative of superannuation emerges, showing that it was a product of long- term institutional continuities, more than existing narratives would suggest. The theory of historical institutionalism is brought to bear to argue that the introduction of Australia’s national superannuation system was the evolution of a welfare system whose architecture was established around the time of Australian Federation. Occupational superannuation had existed in Australia since the 1840s, old age pension schemes were introduced in NSW, Victoria and Queensland in the 1890s, and the Commonwealth Old Age Pension was introduced in 1908.1 The thesis traces the history of debates about public pension financing and the eventual pivot towards Australia’s unique state-mandated, private superannuation system based on defined contributions. -

Paul Keating Wheeler Centre

Conversation between Robert Manne and Paul Keating Wheeler Centre Robert Manne Well, thank you very much … [laughter] Paul Keating I knew I was with a popular guy Robert. Robert Manne I’ll speak about what’s just happened towards the end of today. I have to say, we’ve just heard four musicians from the Australian National Academy of Music, performing Wolf’s Italian Serenade. On violins we had Edwina George and Simone Linley Slattery, on viola Laura Curotta and cello Anna Orzech. The reason we heard them was the Australian National Academy of Music was born out of the vision of Paul Keating, its creation being a major component of his government’s 1994 Creative Nation Policy. [applause] Paul I have to say it is my greatest pleasure and privilege to be invited to do this. Paul Keating Thank you Robert. Robert Manne I hope by the end of my questions, the reason for me saying that will be clear. But anyhow, it’s from the bottom of my heart. Paul Keating Thank you for doing it. You are the best one to do it. [laughter] Robert Manne But I’m going to make sure that it’s not entirely comfortable for either of us, so we want to have a rough and tumble time as well. The reason for this conversation is that Paul Keating has produced what I think is a highly agreeable, highly stimulating and I think vividly and beautifully written book and I recommend it to you. It’s a book with a lot in it, a lot in it, just things that struck me, which I won’t be questioning Paul about, but things that struck me – there is for example an extremely moving eulogy for the musical genius Geoffrey Tozer. -

Evaluating the Organising Model of Trade Unionism

ELR0010.1177/1035304615614520The Economic and Labour Relations ReviewBarnes and Markey 614520research-article2015 ELRR Article The Economic and Labour Relations Review Evaluating the organising 2015, Vol. 26(4) 513 –525 © The Author(s) 2015 model of trade unionism: An Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Australian perspective DOI: 10.1177/1035304615614520 elrr.sagepub.com Alison Barnes and Raymond Markey Macquarie University, Australia Abstract To mark the 20th anniversary of the Australian union movement’s Organising Works programme, this article introduces a symposium discussing potential ways forward for unions. It overviews research regarding the challenges of union organising and renewal, both in Australia and internationally. It provides a broad historical perspective on the origins and progress of the grassroots Organising Works agenda initiated by the peak union bodies, the Australian Council of Trade Unions and Unions NSW. It explores how trade unions can best generate and sustain their spirit of mobilising and organising, while also ensuring the institutional legitimacy they require to effectively represent workers. Unions have had to manage the tension between two dynamics of trade union growth – the sense of movement involved in mobilising workers, and the institutional stability and legitimacy needed to represent workers. Unions have faced both the need to confront global capital restructuring through their own restructuring, and the need to renew and maintain a strong and democratic community -

May/June 2008 [PDF 1.1

MAY JUNE 2008 Child protection studies go global Neuroscientists recognised for obesity research NEW MEDIA SCHOLARSHIPS 84154 Bulletin May08 v5b.indd 1 3/6/08 10:02:34 AM LA TROBE UNIVERSITY NEWS IN THIS ISSUE Home theatre Home theatre – the end of spaghetti junction 2 Mr Boardman says his concept was more Respect for diversity begins The end of complex then just incorporating wireless in schools 3 sensors. ‘The sensors had to be resistant to New media scholarships 3 interference from other wireless signals, Indonesian alumni win awards 4 spaghetti so I needed to source high-quality chips,’ National superannuation – he says. ‘I did some research and found a reflections on the birth company in England that made high-quality of an idea 5 junction? wireless chips for streaming audio, and College life connects with ELecTRONICS GRADUATE Glenn then built a circuit around the chip to make the world 6 Boardman has won the 2008 Victorian it work.’ Dubai womens’ art 6 Institution of Engineering and Technology He also had to figure out how to make it Student Prize for designing wireless Research in Action easy to use by developing intuitive controls, speakers that can reproduce hi-fi sound good compatible with other hardware in the Soil test for safer enough for home-theatre systems. nuclear waste 7 entertainment unit – and how to ensure it In the era of cordless, mobile, and Neuroscience tackles wouldn’t ‘overcook’ itself. obesity epidemic 8 infrared, Mr Boardman asked himself: ‘It also had to look good, so there were Social maps strengthen why -

Keating and Kelty to Speak at ACTU Congress 2012: 15-17 May, Sydney Convention Centre

Wednesday, 28 March 2012 Keating and Kelty to speak at ACTU Congress 2012: 15-17 May, Sydney Convention Centre Former Prime Minister Paul Keating and former ACTU Secretary Bill Kelty have been confirmed as guest speakers at the ACTU Congress in Sydney in May. They will both address the official Congress dinner on 16 May. Mr Keating, the then-Treasurer, and Mr Kelty helped to forge the Accord in the mid-1980s that delivered universal superannuation, Medicare and other social and economic policies from which working people continue to benefit today. ACTU Secretary Jeff Lawrence said he was delighted that Mr Keating and Mr Kelty had accepted invitations to address the Congress. “Both Paul and Bill are giants of the Australian labour movement,” Mr Lawrence said. “They created lasting reforms that we continue to build on today, and are testament to the strong and enduring relationship between unions and the Labor Party. “I expect they will both deliver riveting and inspiring speeches that reinforce to us why we must dedicate ourselves to improving the lives of working Australians and their families.” Almost 1000 delegates representing workers from every industry and sector in Australia will attend the ACTU Congress at the Sydney Convention Centre from 15-17 May. The ACTU Congress is the largest and most important gathering of Australian unions. Delegates will debate and vote on policies regarding the workplace, rights, and campaigns to improve wages, conditions and quality of life for Australian workers and their families. This process sets the union agenda for a further three years. The Congress will also elect a new Secretary to lead the ACTU, along with other office-holders. -

ACTU 75Th Anniversary Commemorative Booklet.Pdf

AUSTRALIAN COUNCIL OF TRADE UNIONS’ 75th anniversary COMMEMORATIVE BOOKLET Autographs THE ACTU 75 YEARS STRONG When union delegates gathered in the Victorian Trades Hall in 1927 to establish the Australian Council of Trade Unions they had a clear vision — to lift the living standards and quality of working life of working people. And their strategy to achieve this was also clear — to build union organisation of the workforce on a national basis. 75 years further on, the ACTU, its affiliated unions and their members can celebrate a proud record of achievement on behalf of working Australians and the community. The industrial gains are many: decades of wage increases through the award system and campaigns in the field, safer workplaces, equality for women, improvements in working hours, entitlements to paid holidays and better employment conditions, and the establishment of a universal superannuation system. The ACTU has played a role in all of these achievements, but has contributed to fairness and justice in the community as well – contributing to Australia’s post-war development and immigration program, the social security system, Medicare and education — to name just a few areas of policy. The ACTU has also represented Australian unionism in the international arena, opposing discrimination and oppression and supporting human rights. The ACTU aid agency, APHEDA — Union Aid Abroad, contributes to humanitarian projects in many countries. The enduring commitment of working Australians to a fairer society is reflected in the continuing fight to protect the fundamental principles of unionism. The right to organise and the right to collectively bargain sit at the heart of the 21st century struggle for a just Australia, just as it did throughout the previous century. -

Download (PDF)

Building and Using Strategic Capacity Labor Union Confederations and Economic Policy John S. Ahlquist A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2008 Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Political Science University of Washington Graduate School This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a doctoral dissertation by John S. Ahlquist and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Margaret Levi Michael D. Ward Reading Committee: Margaret Levi Michael D. Ward Christopher Adolph Erik Wibbels Date: In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the doctoral degree at the University of Washington, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of this dissertation is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for copying or reproduction of this dissertation may be referred to Proquest Information and Learning, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346, 1-800-521-0600, or to the author. Signature Date University of Washington Abstract Building and Using Strategic Capacity Labor Union Confederations and Economic Policy John S. Ahlquist Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Jere L. Bacharach Professor of International Studies Margaret Levi Department of Political Science Professor Michael D. Ward Department of Political Science Mancur Olson made strong claims about the importance of “encompassing” groups for economic performance. -

Foenander Lecture

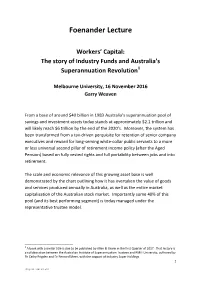

Foenander Lecture Workers’ Capital: The story of Industry Funds and Australia’s Superannuation Revolution1 Melbourne University, 16 November 2016 Garry Weaven From a base of around $40 billion in 1983 Australia’s superannuation pool of savings and investment assets today stands at approximately $2.1 trillion and will likely reach $6 trillion by the end of the 2020’s. Moreover, the system has been transformed from a tax-driven perquisite for retention of senior company executives and reward for long-serving white-collar public servants to a more or less universal second pillar of retirement income policy (after the Aged Pension) based on fully vested rights and full portability between jobs and into retirement. The scale and economic relevance of this growing asset base is well demonstrated by the chart outlining how it has overtaken the value of goods and services produced annually in Australia, as well as the entire market capitalisation of the Australian stock market. Importantly some 40% of this pool (and its best performing segment) is today managed under the representative trustee model. 1 A book with a similar title is due to be published by Allen & Urwin in the first Quarter of 2017. That history is a collaboration between the Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees and RMIT University, authored by Dr Cathy Brigden and Dr Bernard Mees, with the support of Industry Super Holdings. 1 DMS ID: 2401342 v29 GDP, Super Assets and Stock Market Capitalisation (1983 - 2016) ($m) 2,500,000 2,000,000 1,500,000 Annual Nominal GDP ($) Total Super Assets ($) 1,000,000 ASX Market Value ($m) 500,000 - 1987 1998 1999 2010 2011 1983 1984 1985 1986 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Source: ABS and Datastream 1 In international circles I am often asked to explain how we managed in Australia to achieve such a comprehensive system of retirement income. -

Introduction

Introduction “There is a soft sighing murmur in the room and one could easily imagine the spare forms to be automatic figures,” wrote a journalist in 1887 after observing the workers operating the Melbourne telephone exchange.1 Some 114 years later retired telephone exchange worker and union official, Joyce Williams, sounded a quite different note on the world and worldview of telephonists: “I just learnt that you’re never going to get change if you’re going to be tolerant. You’ve got to be totally intolerant about things to get change…”2 It is difficult to imagine two more discordant observations about the same subject. One, an outsider’s perspective recorded near the beginning of telephony’s existence, depicts a workforce somehow less than human, bereft of independent thought and action. The other, a view from the inside during manual telephony’s dying days, signifies a mood of belligerence common amongst telephonists of that time. Chronologically and thematically they would appear to represent the two magnetic poles of the telephonists’ history. Taken at face value they invite an understanding of this history as a movement from unconsciousness to consciousness, a slow class awakening, perhaps even a germination, to use Zola’s allegorical naturalism.3 Such a conception is not altogether flawed. There is no disputing that the telephonists of the 1980s were an altogether more organised and combative group than their counterparts from a century earlier. And certainly some of the militant operators of the latter period saw themselves as torch bearers of a new, higher stage in the union’s history.