Qt9vh4j26d.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walt Disney and the Power of Music James Bohn

Libri & Liberi • 2018 • 7 (1): 167–180 169 The final part of the book is the epilogue entitled “Surviving Childhoodˮ, in which the author shares her thoughts on the importance of literature in childrenʼs lives. She sees literature as an opportunity to keep memories, relate stories to pleasant times from the past, and imagine things which are unreachable or far away. For these reasons, children should be encouraged to read, which will equip them with the skills necessary to create their own associations with reading and creating their own worlds. Finally, The Courage to Imagine demonstrates how literature can influence childrenʼs thinking and help them cope with the world around them. Dealing with topics present in everyday life, such as ethnic diversity, fear, bullying, or empathy, and offering examples of child heroes who overcome their problems, this book will be engaging to teachers and students, as well as experts in the field of childrenʼs literature. Its simple message that through reading children “can escape the adult world and imagine alternativesˮ (108) should be sufficient incentive for everybody to immerse themselves in reading and to start imagining. Josipa Hotovec Walt Disney and the Power of Music James Bohn. 2017. Music in Disneyʼs Animated Features: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Jungle Book. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 294 pp. ISBN 978-1-4968-1214-8 DOI: 10.21066/carcl.libri.2018-07(01).0008 “The essence of a Disney animated feature is not drawn by pencil […]. Rather, it is written in notes”, states James Bohn in the conclusion to his 2017 book Music in Disney’s Animated Features: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to The Jungle Book (201). -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

MUSIC and MOVEMENT in PIXAR: the TSU's AS an ANALYTICAL RESOURCE

Revis ta de Comunicación Vivat Academia ISSN: 1575-2844 Septiembre 2016 Año XIX Nº 136 pp 82-94 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2016.136.82-94 INVESTIGACIÓN/RESEARCH Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 Recibido: 18/12/2015 --- Aceptado: 27/05/2016 --- Publicado: 15/09/2016 MUSIC AND MOVEMENT IN PIXAR: THE TSU’s AS AN ANALYTICAL RESOURCE Diego Calderón Garrido1: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Josep Gustems Carncier: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] Jaume Duran Castells: University of Barcelona. Spain [email protected] ABSTRACT The music for the animation cinema is closely linked with the characters’ movement and the narrative action. This paper presents the Temporary Semiotic Units (TSU’s) proposed by Delalande, as a multimodal tool for the music analysis of the actions in cartoons, following the tradition of the Mickey Mousing. For this, a profile with the applicability of the nineteen TSU’s was applied to the fourteen Pixar movies produced between 1995-2013. The results allow us to state the convenience of the use of the TSU’s for the music comprehension in these films, especially in regard to the subject matter and the characterization of the characters and as a support to the visual narrative of this genre. KEY WORDS Animation cinema, Music – Pixar - Temporary Semiotic Units - Mickey Mousing - Audiovisual Narrative – Multimodality 1 Diego Calderón Garrido: Doctor in History of Art, titled superior in Modern Music and Jazz music teacher and sound in the degree of Audiovisual Communication at the University of Barcelona. -

A Note from the Composer

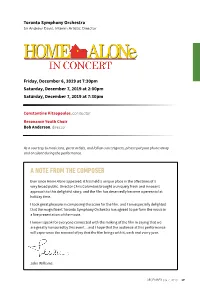

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director Friday, December 6, 2019 at 7:30pm Saturday, December 7, 2019 at 2:00pm Saturday, December 7, 2019 at 7:30pm Constantine Kitsopoulos, conductor Resonance Youth Choir Bob Anderson, director As a courtesy to musicians, guest artists, and fellow concertgoers, please put your phone away and on silent during the performance. A NOTE FROM THE COMPOSER Ever since Home Alone appeared, it has held a unique place in the affections of a very broad public. Director Chris Columbus brought a uniquely fresh and innocent approach to this delightful story, and the film has deservedly become a perennial at holiday time. I took great pleasure in composing the score for the film, and I am especially delighted that the magnificent Toronto Symphony Orchestra has agreed to perform the music in a live presentation of the movie. I know I speak for everyone connected with the making of the film in saying that we are greatly honoured by this event…and I hope that the audience at this performance will experience the renewal of joy that the film brings with it, each and every year. John Williams DECEMBER 6 & 7, 2019 17 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX Presents A JOHN HUGHES Production A CHRIS COLUMBUS Film HOME ALONE Starring MACAULAY CULKIN JOE PESCI DANIEL STERN JOHN HEARD and CATHERINE O’HARA Music by JOHN WILLIAMS Film Editor RAJA GOSNELL Production Designer JOHN MUTO Director of Photography JULIO MACAT Executive Producers MARK LEVINSON & SCOTT ROSENFELT and TARQUIN GOTCH Written and Produced by JOHN HUGHES Directed by CHRIS COLUMBUS Soundtrack Album Available on CBS Records, Cassettes and Compact Discs Color by DELUXE® Tonight’s program is a presentation of the complete filmHome Alone with a live performance of the film’s entire score, including music played by the orchestra during the end credits. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

The Use of Music in the Cinematic Experience

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 2019 The seU of Music in the Cinematic Experience Sarah Schulte Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Schulte, Sarah, "The sU e of Music in the Cinematic Experience" (2019). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 780. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/780 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUND AND EMOTION: THE USE OF MUSIC IN THE CINEMATIC EXPERIENCE A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky Univeristy By Sarah M. Schulte May 2019 ***** CE/T Committee: Professor Matthew Herman, Advisor Professor Ted Hovet Ms. Siera Bramschreiber Copyright by Sarah M. Schulte 2019 Dedicated to my family and friends ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the help and support of so many people. I am incredibly grateful to my faculty advisor, Dr. Matthew Herman. Without your wisdom on the intricacies of composition and your constant encouragement, this project would not have been possible. To Dr. Ted Hovet, thank you for believing in this project from the start. I could not have done it without your reassurance and guidance. -

To See the 2018 Tanglewood Schedule

summer 2018 BERNSTEIN CENTENNIAL SUMMER TANGLEWOOD.ORG 1 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ANDRIS NELSONS MUSIC DIRECTOR “That place [Tanglewood] is very dear to my heart, that is where I grew up and learned so much...in 1940 when I first played and studied there.” —Leonard Bernstein (November 1989) SEASONHIGHLIGHTS Throughoutthesummerof2018,Tanglewoodcelebratesthecentennialof AlsoleadingBSOconcertswillbeBSOArtisticPartnerThomas Adès(7/22), Lawrence-born,Boston-bredconductor-composerLeonardBernstein’sbirth. BSOAssistantConductorMoritz Gnann(7/13),andguestconductorsHerbert Bernstein’scloserelationshipwiththeBostonSymphonyOrchestraspanned Blomstedt(7/20&21),Charles Dutoit(8/3&8/5),Christoph Eschenbach ahalf-century,fromthetimehebecameaprotégéoflegendaryBSO (8/26),Juanjo Mena(7/27&29),David Newman(7/28),Michael Tilson conductorSergeKoussevitzkyasamemberofthefirstTanglewoodMusic Thomas(8/12),andBramwell Tovey(8/4).SoloistswiththeBSOalsoinclude Centerclassin1940untilthefinalconcertsheeverconducted,withtheBSO pianistsEmanuel Ax(7/20),2018KoussevitzkyArtistKirill Gerstein(8/3),Igor andTanglewoodMusicCenterOrchestraatTanglewoodin1990.Besides Levit(8/12),Paul Lewis(7/13),andGarrick Ohlsson(7/27);BSOprincipalflute concertworksincludinghisChichester Psalms(7/15), alilforfluteand Elizabeth Rowe(7/21);andviolinistsJoshua Bell(8/5),Gil Shaham(7/29),and orchestra(7/21),Songfest(8/4),theSerenade (after Plato’s “Symposium”) Christian Tetzlaff(7/22). (8/18),andtheBSO-commissionedDivertimentoforOrchestra(also8/18), ThomasAdèswillalsodirectTanglewood’s2018FestivalofContemporary -

The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition

The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition By Michelle L. Walsh Submitted to the Faculty of the Information Technology Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Information Technology University of Cincinnati College of Applied Science June 2006 The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation Interactive Edition by Michelle L. Walsh Submitted to the Faculty of the Information Technology Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Information Technology © Copyright 2006 Michelle Walsh The author grants to the Information Technology Program permission to reproduce and distribute copies of this document in whole or in part. ___________________________________________________ __________________ Michelle L. Walsh Date ___________________________________________________ __________________ Sam Geonetta, Faculty Advisor Date ___________________________________________________ __________________ Patrick C. Kumpf, Ed.D. Interim Department Head Date Acknowledgements A great many people helped me with support and guidance over the course of this project. I would like to give special thanks to Sam Geonetta and Russ McMahon for working with me to complete this project via distance learning due to an unexpected job transfer at the beginning of my final year before completing my Bachelor’s degree. Additionally, the encouragement of my family, friends and coworkers was instrumental in keeping my motivation levels high. Specific thanks to my uncle, Keith -

Season 2016-2017

23 Season 2016-2017 Friday, March 17, at 7:00 Saturday, March 18, at 7:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Sunday, March 19, at 2:00 David Newman Conductor Paramount Pictures Presents A Lucasfilm Ltd. Production A Steven Spielberg Film in Concert Starring Harrison Ford Karen Allen Paul Freeman Ronald Lacey John Rhys-Davies Denholm Elliott Music by John Williams Executive Producers George Lucas and Howard Kazanjian Screenplay by Lawrence Kasdan Story by George Lucas and Philip Kaufman Produced by Frank Marshall Directed by Steven Spielberg Raiders of the Lost Ark licensed by Lucasfilm Ltd. and Paramount Pictures. This program licensed by Lucasfilm Ltd. and Paramount Pictures. Motion picture, artwork, photos © 1981 Lucasfilm Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Music written by John Williams, Bantha Music (BMI). All rights administered by Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp. (BMI). All rights reserved. Used by permission. This program runs approximately 2 hours, 15 minutes. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 25 PRODUCTION CREDITS Raiders of the Lost Ark—Film with Orchestra produced by Film Concerts Live!, a joint venture of IMG Artists, LLC, and the Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. Producers: Steven A. Linder and Jamie Richardson Production Manager: Rob Stogsdill Production Coordinator: Rebekah Wood Worldwide Representation: IMG Artists, LLC Supervising Technical Director: Mike Runice Technical Director: Luke Dennis Music composed by John Williams Music Preparation: Jo Ann Kane Music Service Film Preparation for Concert Performance: Ramiro Belgardt Technical Consultant: Laura Gibson Sound Remixing for Concert Performance: Chace Audio by Deluxe The score for Raiders of the Lost Ark has been adapted for live concert performance. -

Cartoons & Counterculture

Cartoons & Counterculture Azure Star Glover Introduction Entertainment media is one of the United States’ most lucrative and influential exports, and Hollywood, in Los Angeles County, California, has historically been the locus of such media’s production. While much study has been done on the subject of film and the connection between Hollywood and Los Angeles as a whole, there exists less scholarship on the topic of animated Hollywood productions, even less on the topic of changing rhetoric in animated features, and a dearth of information regarding the rise and influence of independent, so-called “indie” animation. This paper aims to synthesize scholarship on and close reading of the rhetoric of early Disney animated films such as Snow White and more modern cartoon television series such as The Simpsons with that of recently popular independently-created cartoon features such as “Narwhals,” with the goal of tracing the evolution of the rhetoric of cartoons created and produced in Hollywood and their corresponding reflection of Los Angeles culture. Hollywood and Animation In a 2012 report commissioned by the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, The Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation acknowledged that “[f]or many people, the words Los Angeles and Hollywood are synonymous with entertainment” (“The Entertainment Industry” 1), and with good reason: Los Angeles’s year-round fair weather first attracted live-action filmmakers in the early 1900s, and filming-friendly Hollywood slowly grew into a Mecca of entertainment media production. In 2011, the entertainment industry accounted for “nearly 5% of the 3.3 million private sector wage and salary professionals and other independent contract workers,” generating over $120 billion in annual revenue (8.4% of Los Angeles County’s 2011 estimated annual Gross County Product), making this “one of the largest industries in the country” (“The 76 Azure Star Glover Entertainment Industry” 2). -

Tanglewood the Tanglewood Festival

boston symphony orchestra summer 2013 Bernard Haitink, LaCroix Family Fund Conductor Emeritus, Endowed in Perpetuity Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 132nd season, 2012–2013 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Edmund Kelly, Chairman • Paul Buttenwieser, Vice-Chairman • Diddy Cullinane, Vice-Chairman • Stephen B. Kay, Vice-Chairman • Robert P. O’Block, Vice-Chairman • Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman • Stephen R. Weber, Vice-Chairman • Theresa M. Stone, Treasurer William F. Achtmeyer • George D. Behrakis • Jan Brett • Susan Bredhoff Cohen, ex-officio • Richard F. Connolly, Jr. • Cynthia Curme • Alan J. Dworsky • William R. Elfers • Thomas E. Faust, Jr. • Nancy J. Fitzpatrick • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Charles W. Jack, ex-officio • Charles H. Jenkins, Jr. • Joyce G. Linde • John M. Loder • Nancy K. Lubin • Carmine A. Martignetti • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. • Susan W. Paine • Peter Palandjian, ex-officio • Carol Reich • Arthur I. Segel • Thomas G. Stemberg • Caroline Taylor • Stephen R. Weiner • Robert C. Winters Life Trustees Vernon R. Alden • Harlan E. Anderson • David B. Arnold, Jr. • J.P. Barger • Leo L. Beranek • Deborah Davis Berman • Peter A. Brooke • John F. Cogan, Jr. • Mrs. Edith L. Dabney • Nelson J. Darling, Jr. • Nina L. Doggett • Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick • Thelma E. Goldberg • Mrs. Béla T. Kalman • George Krupp • Mrs. Henrietta N. Meyer • Nathan R. Miller • Richard P. Morse • David Mugar • Mary S. Newman • Vincent M. O’Reilly • William J. Poorvu • Peter C. Read • Edward I. Rudman • Richard A. Smith • Ray Stata • John Hoyt Stookey • Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. • John L. Thorndike • Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas Other Officers of the Corporation Mark Volpe, Managing Director • Thomas D. -

To Rock Or Not Torock?

v7n3cov 4/21/02 10:12 AM Page c1 ORIGINAL MUSIC SOUNDTRACKS FOR MOTION PICTURES AND TV V OLUME 7, NUMBER 3 Exclusive interview with Tom Conti! TOTO ROCK ROCK OROR NOTNOT TOROCK?TOROCK? CanCan youyou smellsmell whatwhat JohnJohn DebneyDebney isis cooking?cooking? JOHNWILLIAMSJOHNWILLIAMS’’ HOOKHOOK ReturnReturn toto NeverlandNeverland DIALECTDIALECT OFOF DESIREDESIRE TheThe eroticerotic voicevoice ofof ItalianItalian cinemacinema THETHE MANWHO CAN-CAN-CANCAN-CAN-CAN MeetMeet thethe maestromaestro ofof MoulinMoulin Rouge!Rouge! PLUSPLUS HowardHoward ShoreShore && RandyRandy NewmanNewman getget theirs!theirs! 03> 7225274 93704 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada v7n3cov 4 /19/02 4 :29 PM P age c2 composers musicians record labels music publishers equipment manufacturers software manufacturers music editors music supervisors music clear- Score with ance arrangers soundtrack our readers. labels contractors scoring stages orchestrators copyists recording studios dubbing prep dubbing rescoring music prep scoring mixers Film & TV Music Series 2002 If you contribute in any way to the film music process, our four Film & TV Music Special Issues provide a unique marketing opportunity for your talent, product or service throughout the year. Film & TV Music Summer Edition: August 20, 2002 Space Deadline: August 1 | Materials Deadline: August 7 Film & TV Music Fall Edition: November 5, 2002 Space Deadline: October 18 | Materials Deadline: October 24 LA Judi Pulver (323) 525-2026, NY John Troyan (646) 654-5624, UK John Kania +(44-208) 694-0104 www.hollywoodreporter.com v7n03 issue 4/19/02 3:09 PM Page 1 CONTENTS MARCH/APRIL 2002 cover story departments 14 To Rock or Not to Rock? 2 Editorial Like it or hate it (okay, hate it), the rock score is Happy 70th, Maestro! here to stay.