Physics, Chapter 10: Momentum and Impulse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Key Concepts for Future QIS Learners Workshop Output Published Online May 13, 2020

Key Concepts for Future QIS Learners Workshop output published online May 13, 2020 Background and Overview On behalf of the Interagency Working Group on Workforce, Industry and Infrastructure, under the NSTC Subcommittee on Quantum Information Science (QIS), the National Science Foundation invited 25 researchers and educators to come together to deliberate on defining a core set of key concepts for future QIS learners that could provide a starting point for further curricular and educator development activities. The deliberative group included university and industry researchers, secondary school and college educators, and representatives from educational and professional organizations. The workshop participants focused on identifying concepts that could, with additional supporting resources, help prepare secondary school students to engage with QIS and provide possible pathways for broader public engagement. This workshop report identifies a set of nine Key Concepts. Each Concept is introduced with a concise overall statement, followed by a few important fundamentals. Connections to current and future technologies are included, providing relevance and context. The first Key Concept defines the field as a whole. Concepts 2-6 introduce ideas that are necessary for building an understanding of quantum information science and its applications. Concepts 7-9 provide short explanations of critical areas of study within QIS: quantum computing, quantum communication and quantum sensing. The Key Concepts are not intended to be an introductory guide to quantum information science, but rather provide a framework for future expansion and adaptation for students at different levels in computer science, mathematics, physics, and chemistry courses. As such, it is expected that educators and other community stakeholders may not yet have a working knowledge of content covered in the Key Concepts. -

Non-Local Momentum Transport Parameterizations

Non-local Momentum Transport Parameterizations Joe Tribbia NCAR.ESSL.CGD.AMP Outline • Historical view: gravity wave drag (GWD) and convective momentum transport (CMT) • GWD development -semi-linear theory -impact • CMT development -theory -impact Both parameterizations of recent vintage compared to radiation or PBL GWD CMT • 1960’s discussion by Philips, • 1972 cumulus vorticity Blumen and Bretherton damping ‘observed’ Holton • 1970’s quantification Lilly • 1976 Schneider and and momentum budget by Lindzen -Cumulus Friction Swinbank • 1980’s NASA GLAS model- • 1980’s incorporation into Helfand NWP and climate models- • 1990’s pressure term- Miller and Palmer and Gregory McFarlane Atmospheric Gravity Waves Simple gravity wave model Topographic Gravity Waves and Drag • Flow over topography generates gravity (i.e. buoyancy) waves • <u’w’> is positive in example • Power spectrum of Earth’s topography α k-2 so there is a lot of subgrid orography • Subgrid orography generating unresolved gravity waves can transport momentum vertically • Let’s parameterize this mechanism! Begin with linear wave theory Simplest model for gravity waves: with Assume w’ α ei(kx+mz-σt) gives the dispersion relation or Linear theory (cont.) Sinusoidal topography ; set σ=0. Gives linear lower BC Small scale waves k>N/U0 decay Larger scale waves k<N/U0 propagate Semi-linear Parameterization Propagating solution with upward group velocity In the hydrostatic limit The surface drag can be related to the momentum transport δh=isentropic Momentum transport invariant by displacement Eliassen-Palm. Deposited when η=U linear theory is invalid (CL, breaking) z φ=phase Gravity Wave Drag Parameterization Convective or shear instabilty begins to dissipate wave- momentum flux no longer constant Waves propagate vertically, amplitude grows as r-1/2 (energy force cons.). -

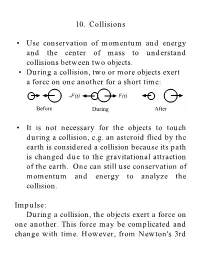

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

Lecture 10: Impulse and Momentum

ME 230 Kinematics and Dynamics Wei-Chih Wang Department of Mechanical Engineering University of Washington Kinetics of a particle: Impulse and Momentum Chapter 15 Chapter objectives • Develop the principle of linear impulse and momentum for a particle • Study the conservation of linear momentum for particles • Analyze the mechanics of impact • Introduce the concept of angular impulse and momentum • Solve problems involving steady fluid streams and propulsion with variable mass W. Wang Lecture 10 • Kinetics of a particle: Impulse and Momentum (Chapter 15) - 15.1-15.3 W. Wang Material covered • Kinetics of a particle: Impulse and Momentum - Principle of linear impulse and momentum - Principle of linear impulse and momentum for a system of particles - Conservation of linear momentum for a system of particles …Next lecture…Impact W. Wang Today’s Objectives Students should be able to: • Calculate the linear momentum of a particle and linear impulse of a force • Apply the principle of linear impulse and momentum • Apply the principle of linear impulse and momentum to a system of particles • Understand the conditions for conservation of momentum W. Wang Applications 1 A dent in an automotive fender can be removed using an impulse tool, which delivers a force over a very short time interval. How can we determine the magnitude of the linear impulse applied to the fender? Could you analyze a carpenter’s hammer striking a nail in the same fashion? W. Wang Applications 2 Sure! When a stake is struck by a sledgehammer, a large impulsive force is delivered to the stake and drives it into the ground. -

Impulse and Momentum

Impulse and Momentum All particles with mass experience the effects of impulse and momentum. Momentum and inertia are similar concepts that describe an objects motion, however inertia describes an objects resistance to change in its velocity, and momentum refers to the magnitude and direction of it's motion. Momentum is an important parameter to consider in many situations such as braking in a car or playing a game of billiards. An object can experience both linear momentum and angular momentum. The nature of linear momentum will be explored in this module. This section will discuss momentum and impulse and the interconnection between them. We will explore how energy lost in an impact is accounted for and the relationship of momentum to collisions between two bodies. This section aims to provide a better understanding of the fundamental concept of momentum. Understanding Momentum Any body that is in motion has momentum. A force acting on a body will change its momentum. The momentum of a particle is defined as the product of the mass multiplied by the velocity of the motion. Let the variable represent momentum. ... Eq. (1) The Principle of Momentum Recall Newton's second law of motion. ... Eq. (2) This can be rewritten with accelleration as the derivate of velocity with respect to time. ... Eq. (3) If this is integrated from time to ... Eq. (4) Moving the initial momentum to the other side of the equation yields ... Eq. (5) Here, the integral in the equation is the impulse of the system; it is the force acting on the mass over a period of time to . -

Exercises in Classical Mechanics 1 Moments of Inertia 2 Half-Cylinder

Exercises in Classical Mechanics CUNY GC, Prof. D. Garanin No.1 Solution ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| 1 Moments of inertia (5 points) Calculate tensors of inertia with respect to the principal axes of the following bodies: a) Hollow sphere of mass M and radius R: b) Cone of the height h and radius of the base R; both with respect to the apex and to the center of mass. c) Body of a box shape with sides a; b; and c: Solution: a) By symmetry for the sphere I®¯ = I±®¯: (1) One can ¯nd I easily noticing that for the hollow sphere is 1 1 X ³ ´ I = (I + I + I ) = m y2 + z2 + z2 + x2 + x2 + y2 3 xx yy zz 3 i i i i i i i i 2 X 2 X 2 = m r2 = R2 m = MR2: (2) 3 i i 3 i 3 i i b) and c): Standard solutions 2 Half-cylinder ϕ (10 points) Consider a half-cylinder of mass M and radius R on a horizontal plane. a) Find the position of its center of mass (CM) and the moment of inertia with respect to CM. b) Write down the Lagrange function in terms of the angle ' (see Fig.) c) Find the frequency of cylinder's oscillations in the linear regime, ' ¿ 1. Solution: (a) First we ¯nd the distance a between the CM and the geometrical center of the cylinder. With σ being the density for the cross-sectional surface, so that ¼R2 M = σ ; (3) 2 1 one obtains Z Z 2 2σ R p σ R q a = dx x R2 ¡ x2 = dy R2 ¡ y M 0 M 0 ¯ 2 ³ ´3=2¯R σ 2 2 ¯ σ 2 3 4 = ¡ R ¡ y ¯ = R = R: (4) M 3 0 M 3 3¼ The moment of inertia of the half-cylinder with respect to the geometrical center is the same as that of the cylinder, 1 I0 = MR2: (5) 2 The moment of inertia with respect to the CM I can be found from the relation I0 = I + Ma2 (6) that yields " µ ¶ # " # 1 4 2 1 32 I = I0 ¡ Ma2 = MR2 ¡ = MR2 1 ¡ ' 0:3199MR2: (7) 2 3¼ 2 (3¼)2 (b) The Lagrange function L is given by L('; '_ ) = T ('; '_ ) ¡ U('): (8) The potential energy U of the half-cylinder is due to the elevation of its CM resulting from the deviation of ' from zero. -

Optimum Design of Impulse Ventilation System in Underground

ering & ine M g a n n , E a Umamaheswararao Ind Eng Manage 2017, 6:4 l g a i e r m t s DOI: 10.4172/2169-0316.1000238 e u n d t n I Industrial Engineering & Management ISSN: 2169-0316 Research Article Open Access Optimum Design of Impulse Ventilation System in Underground Car Parking Basement by Using CFD Simulation Lakamana Umamaheswararao* Design and Development Engineer, Saudi Fan Industries, KSA Abstract The most significant development in car park ventilation design has been the introduction of Impulse Ventilation. It is an innovative alternative to traditional systems and provides a number of significant benefits. The ventilation of car parks is essential for removing vehicle exhausts Fumes and smoke in case of fire containing harmful pollutants. So design of impulse systems is usually proven by use of CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamic) analysis. In this study considered one of the car parking basement which is in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and study was conducted by using ANSYS-Fluent. The field study was carried to collect the actual data of boundary conditions for CFD simulation. In this study, two Cases of jet fan smoke ventilation systems were considered, one has 8 jet fans according to the customer and another one has 11 jet fans which positions were changed accordingly. Base on the comparison of simulation data, ventilation system with 11 jet fans can help to improve the evacuation of fumes in the car parking area and it is also observed that the concentration of CO minimized within 15 minutes. Keywords: Impulse ventilation; CFD; AMC hospital; Jet fans The CFD model accounted for columns, beams, internal walls and other construction elements which could form an obstruction to the Introduction air flow as shown in Figure 1 and total car parking area is 3500 2m . -

Fluids – Lecture 7 Notes 1

Fluids – Lecture 7 Notes 1. Momentum Flow 2. Momentum Conservation Reading: Anderson 2.5 Momentum Flow Before we can apply the principle of momentum conservation to a fixed permeable control volume, we must first examine the effect of flow through its surface. When material flows through the surface, it carries not only mass, but momentum as well. The momentum flow can be described as −→ −→ momentum flow = (mass flow) × (momentum /mass) where the mass flow was defined earlier, and the momentum/mass is simply the velocity vector V~ . Therefore −→ momentum flow =m ˙ V~ = ρ V~ ·nˆ A V~ = ρVnA V~ where Vn = V~ ·nˆ as before. Note that while mass flow is a scalar, the momentum flow is a vector, and points in the same direction as V~ . The momentum flux vector is defined simply as the momentum flow per area. −→ momentum flux = ρVn V~ V n^ . mV . A m ρ Momentum Conservation Newton’s second law states that during a short time interval dt, the impulse of a force F~ applied to some affected mass, will produce a momentum change dP~a in that affected mass. When applied to a fixed control volume, this principle becomes F dP~ a = F~ (1) dt V . dP~ ˙ ˙ P(t) P + P~ − P~ = F~ (2) . out dt out in Pin 1 In the second equation (2), P~ is defined as the instantaneous momentum inside the control volume. P~ (t) ≡ ρ V~ dV ZZZ ˙ The P~ out is added because mass leaving the control volume carries away momentum provided ˙ by F~ , which P~ alone doesn’t account for. -

Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗

SIAM REVIEW c 2008 Walter Gautschi Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 3–33 Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗ Walter Gautschi† Abstract. On the occasion of the 300th anniversary (on April 15, 2007) of Euler’s birth, an attempt is made to bring Euler’s genius to the attention of a broad segment of the educated public. The three stations of his life—Basel, St. Petersburg, andBerlin—are sketchedandthe principal works identified in more or less chronological order. To convey a flavor of his work andits impact on modernscience, a few of Euler’s memorable contributions are selected anddiscussedinmore detail. Remarks on Euler’s personality, intellect, andcraftsmanship roundout the presentation. Key words. LeonhardEuler, sketch of Euler’s life, works, andpersonality AMS subject classification. 01A50 DOI. 10.1137/070702710 Seh ich die Werke der Meister an, So sehe ich, was sie getan; Betracht ich meine Siebensachen, Seh ich, was ich h¨att sollen machen. –Goethe, Weimar 1814/1815 1. Introduction. It is a virtually impossible task to do justice, in a short span of time and space, to the great genius of Leonhard Euler. All we can do, in this lecture, is to bring across some glimpses of Euler’s incredibly voluminous and diverse work, which today fills 74 massive volumes of the Opera omnia (with two more to come). Nine additional volumes of correspondence are planned and have already appeared in part, and about seven volumes of notebooks and diaries still await editing! We begin in section 2 with a brief outline of Euler’s life, going through the three stations of his life: Basel, St. -

Impulse Response of Civil Structures from Ambient Noise Analysis by German A

Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 100, No. 5A, pp. 2322–2328, October 2010, doi: 10.1785/0120090285 Ⓔ Short Note Impulse Response of Civil Structures from Ambient Noise Analysis by German A. Prieto, Jesse F. Lawrence, Angela I. Chung, and Monica D. Kohler Abstract Increased monitoring of civil structures for response to earthquake motions is fundamental to reducing seismic risk. Seismic monitoring is difficult because typically only a few useful, intermediate to large earthquakes occur per decade near instrumented structures. Here, we demonstrate that the impulse response function (IRF) of a multistory building can be generated from ambient noise. Estimated shear- wave velocity, attenuation values, and resonance frequencies from the IRF agree with previous estimates for the instrumented University of California, Los Angeles, Factor building. The accuracy of the approach is demonstrated by predicting the Factor build- ing’s response to an M 4.2 earthquake. The methodology described here allows for rapid, noninvasive determination of structural parameters from the IRFs within days and could be used for state-of-health monitoring of civil structures (buildings, bridges, etc.) before and/or after major earthquakes. Online Material: Movies of IRF and earthquake shaking. Introduction Determining a building’s response to earthquake an elastic medium from one point to another; traditionally, it motions for risk assessment is a primary goal of seismolo- is the response recorded at a receiver when a unit impulse is gists and structural engineers alike (e.g., Cader, 1936a,b; applied at a source location at time 0. Çelebi et al., 1993; Clinton et al., 2006; Snieder and Safak, In many studies using ambient vibrations from engineer- 2006; Chopra, 2007; Kohler et al., 2007). -

Quantum Mechanics

Quantum Mechanics Richard Fitzpatrick Professor of Physics The University of Texas at Austin Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Intendedaudience................................ 5 1.2 MajorSources .................................. 5 1.3 AimofCourse .................................. 6 1.4 OutlineofCourse ................................ 6 2 Probability Theory 7 2.1 Introduction ................................... 7 2.2 WhatisProbability?.............................. 7 2.3 CombiningProbabilities. ... 7 2.4 Mean,Variance,andStandardDeviation . ..... 9 2.5 ContinuousProbabilityDistributions. ........ 11 3 Wave-Particle Duality 13 3.1 Introduction ................................... 13 3.2 Wavefunctions.................................. 13 3.3 PlaneWaves ................................... 14 3.4 RepresentationofWavesviaComplexFunctions . ....... 15 3.5 ClassicalLightWaves ............................. 18 3.6 PhotoelectricEffect ............................. 19 3.7 QuantumTheoryofLight. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 3.8 ClassicalInterferenceofLightWaves . ...... 21 3.9 QuantumInterferenceofLight . 22 3.10 ClassicalParticles . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 3.11 QuantumParticles............................... 25 3.12 WavePackets .................................. 26 2 QUANTUM MECHANICS 3.13 EvolutionofWavePackets . 29 3.14 Heisenberg’sUncertaintyPrinciple . ........ 32 3.15 Schr¨odinger’sEquation . 35 3.16 CollapseoftheWaveFunction . 36 4 Fundamentals of Quantum Mechanics 39 4.1 Introduction ..................................