CIS 192: Lecture 12 Deploying Apps and Concurrency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ironpython in Action

IronPytho IN ACTION Michael J. Foord Christian Muirhead FOREWORD BY JIM HUGUNIN MANNING IronPython in Action Download at Boykma.Com Licensed to Deborah Christiansen <[email protected]> Download at Boykma.Com Licensed to Deborah Christiansen <[email protected]> IronPython in Action MICHAEL J. FOORD CHRISTIAN MUIRHEAD MANNING Greenwich (74° w. long.) Download at Boykma.Com Licensed to Deborah Christiansen <[email protected]> For online information and ordering of this and other Manning books, please visit www.manning.com. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity. For more information, please contact Special Sales Department Manning Publications Co. Sound View Court 3B fax: (609) 877-8256 Greenwich, CT 06830 email: [email protected] ©2009 by Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps. Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15% recycled and processed without the use of elemental chlorine. -

Threading and GUI Issues for R

Threading and GUI Issues for R Luke Tierney School of Statistics University of Minnesota March 5, 2001 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Concurrency and Parallelism 2 3 Concurrency and Dynamic State 3 3.1 Options Settings . 3 3.2 User Defined Options . 5 3.3 Devices and Par Settings . 5 3.4 Standard Connections . 6 3.5 The Context Stack . 6 3.5.1 Synchronization . 6 4 GUI Events And Blocking IO 6 4.1 UNIX Issues . 7 4.2 Win32 Issues . 7 4.3 Classic MacOS Issues . 8 4.4 Implementations To Consider . 8 4.5 A Note On Java . 8 4.6 A Strategy for GUI/IO Management . 9 4.7 A Sample Implementation . 9 5 Threads and GUI’s 10 6 Threading Design Space 11 6.1 Parallelism Through HL Threads: The MXM Options . 12 6.2 Light-Weight Threads: The XMX Options . 12 6.3 Multiple OS Threads Running One At A Time: MSS . 14 6.4 Variations on OS Threads . 14 6.5 SMS or MXS: Which To Choose? . 14 7 Light-Weight Thread Implementation 14 1 March 5, 2001 2 8 Other Issues 15 8.1 High-Level GUI Interfaces . 16 8.2 High-Level Thread Interfaces . 16 8.3 High-Level Streams Interfaces . 16 8.4 Completely Random Stuff . 16 1 Introduction This document collects some random thoughts on runtime issues relating to concurrency, threads, GUI’s and the like. Some of this is extracted from recent R-core email threads. I’ve tried to provide lots of references that might be of use. -

Due to Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), Python Threads Do Not Provide Efficient Multi-Core Execution, Unlike Other Languages Such As Golang

Due to global interpreter lock (GIL), python threads do not provide efficient multi-core execution, unlike other languages such as golang. Asynchronous programming in python is focusing on single core execution. Happily, Nexedi python code base already supports high performance multi-core execution either through multiprocessing with distributed shared memory or by relying on components (NumPy, MariaDB) that already support multiple core execution. The impatient reader will find bellow a table that summarises current options to achieve high performance multi-core performance in python. High Performance multi-core Python Cheat Sheet Use python whenever you can rely on any of... Use golang whenever you need at the same time... low latency multiprocessing high concurrency cython's nogil option multi-core execution within single userspace shared multi-core execution within wendelin.core distributed memory shared memory something else than cython's parallel module or cython's parallel module nogil option Here are a set of rules to achieve high performance on a multi-core system in the context of Nexedi stack. use ERP5's CMFActivity by default, since it can solve 99% of your concurrency and performance problems on a cluster or multi-core system; use parallel module in cython if you need to use all cores with high performance within a single transaction (ex. HTTP request); use threads in python together with nogil option in cython in order to use all cores on a multithreaded python process (ex. Zope); use cython to achieve C/C++ performance without mastering C/C++ as long as you do not need multi-core asynchronous programming; rewrite some python in cython to get performance boost on selected portions of python libraries; use numba to accelerate selection portions of python code with JIT that may also work in a dynamic context (ex. -

Specialising Dynamic Techniques for Implementing the Ruby Programming Language

SPECIALISING DYNAMIC TECHNIQUES FOR IMPLEMENTING THE RUBY PROGRAMMING LANGUAGE A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences 2015 By Chris Seaton School of Computer Science This published copy of the thesis contains a couple of minor typographical corrections from the version deposited in the University of Manchester Library. [email protected] chrisseaton.com/phd 2 Contents List of Listings7 List of Tables9 List of Figures 11 Abstract 15 Declaration 17 Copyright 19 Acknowledgements 21 1 Introduction 23 1.1 Dynamic Programming Languages.................. 23 1.2 Idiomatic Ruby............................ 25 1.3 Research Questions.......................... 27 1.4 Implementation Work......................... 27 1.5 Contributions............................. 28 1.6 Publications.............................. 29 1.7 Thesis Structure............................ 31 2 Characteristics of Dynamic Languages 35 2.1 Ruby.................................. 35 2.2 Ruby on Rails............................. 36 2.3 Case Study: Idiomatic Ruby..................... 37 2.4 Summary............................... 49 3 3 Implementation of Dynamic Languages 51 3.1 Foundational Techniques....................... 51 3.2 Applied Techniques.......................... 59 3.3 Implementations of Ruby....................... 65 3.4 Parallelism and Concurrency..................... 72 3.5 Summary............................... 73 4 Evaluation Methodology 75 4.1 Evaluation Philosophy -

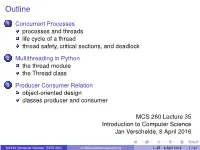

Multithreaded Programming L-35 8April2016 1/41 Lifecycle of a Thread Multithreaded Programming

Outline 1 Concurrent Processes processes and threads life cycle of a thread thread safety, critical sections, and deadlock 2 Multithreading in Python the thread module the Thread class 3 Producer Consumer Relation object-oriented design classes producer and consumer MCS 260 Lecture 35 Introduction to Computer Science Jan Verschelde, 8 April 2016 Intro to Computer Science (MCS 260) multithreaded programming L-35 8April2016 1/41 lifecycle of a thread multithreaded programming 1 Concurrent Processes processes and threads life cycle of a thread thread safety, critical sections, and deadlock 2 Multithreading in Python the thread module the Thread class 3 Producer Consumer Relation object-oriented design classes producer and consumer Intro to Computer Science (MCS 260) multithreaded programming L-35 8April2016 2/41 concurrency and parallelism First some terminology: concurrency Concurrent programs execute multiple tasks independently. For example, a drawing application, with tasks: ◮ receiving user input from the mouse pointer, ◮ updating the displayed image. parallelism A parallel program executes two or more tasks in parallel with the explicit goal of increasing the overall performance. For example: a parallel Monte Carlo simulation for π, written with the multiprocessing module of Python. Every parallel program is concurrent, but not every concurrent program executes in parallel. Intro to Computer Science (MCS 260) multithreaded programming L-35 8April2016 3/41 Parallel Processing processes and threads At any given time, many processes are running simultaneously on a computer. The operating system employs time sharing to allocate a percentage of the CPU time to each process. Consider for example the downloading of an audio file. Instead of having to wait till the download is complete, we would like to listen sooner. -

A Tale of Two Concurrencies (Part 1) DAVIDCOLUMNS BEAZLEY

A Tale of Two Concurrencies (Part 1) DAVIDCOLUMNS BEAZLEY David Beazley is an open alk to any Python programmer long enough and eventually the topic source developer and author of of concurrent programming will arise—usually followed by some the Python Essential Reference groans, some incoherent mumbling about the dreaded global inter- (4th Edition, Addison-Wesley, T 2009). He is also known as the preter lock (GIL), and a request to change the topic. Yet Python continues to creator of Swig (www.swig.org) and Python be used in a lot of applications that require concurrent operation whether it Lex-Yacc (www.dabeaz.com/ply.html). Beazley is a small Web service or full-fledged application. To support concurrency, is based in Chicago, where he also teaches a Python provides both support for threads and coroutines. However, there is variety of Python courses. [email protected] often a lot of confusion surrounding both topics. So in the next two install- ments, we’re going to peel back the covers and take a look at the differences and similarities in the two approaches, with an emphasis on their low-level interaction with the system. The goal is simply to better understand how things work in order to make informed decisions about larger libraries and frameworks. To get the most out of this article, I suggest that you try the examples yourself. I’ve tried to strip them down to their bare essentials so there’s not so much code—the main purpose is to try some simple experiments. The article assumes the use of Python 3.3 or newer. -

Comparative Studies of Six Programming Languages

Comparative Studies of Six Programming Languages Zakaria Alomari Oualid El Halimi Kaushik Sivaprasad Chitrang Pandit Concordia University Concordia University Concordia University Concordia University Montreal, Canada Montreal, Canada Montreal, Canada Montreal, Canada [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Comparison of programming languages is a common topic of discussion among software engineers. Multiple programming languages are designed, specified, and implemented every year in order to keep up with the changing programming paradigms, hardware evolution, etc. In this paper we present a comparative study between six programming languages: C++, PHP, C#, Java, Python, VB ; These languages are compared under the characteristics of reusability, reliability, portability, availability of compilers and tools, readability, efficiency, familiarity and expressiveness. 1. Introduction: Programming languages are fascinating and interesting field of study. Computer scientists tend to create new programming language. Thousand different languages have been created in the last few years. Some languages enjoy wide popularity and others introduce new features. Each language has its advantages and drawbacks. The present work provides a comparison of various properties, paradigms, and features used by a couple of popular programming languages: C++, PHP, C#, Java, Python, VB. With these variety of languages and their widespread use, software designer and programmers should to be aware -

Embedding Concurrency: a Lua Case Study

ISSN 0103-9741 Monografias em Cienciaˆ da Computac¸ao˜ no 13/11 Embedding Concurrency: A Lua Case Study Alexandre Rupert Arpini Skyrme Noemi de La Rocque Rodriguez Pablo Martins Musa Roberto Ierusalimschy Bruno Oliveira Silvestre Departamento de Informatica´ PONTIF´ICIA UNIVERSIDADE CATOLICA´ DO RIO DE JANEIRO RUA MARQUESˆ DE SAO˜ VICENTE, 225 - CEP 22451-900 RIO DE JANEIRO - BRASIL Monografias em Cienciaˆ da Computac¸ao,˜ No. 13/11 ISSN: 0103-9741 Editor: Prof. Carlos Jose´ Pereira de Lucena September, 2011 Embedding Concurrency: A Lua Case Study Alexandre Rupert Arpini Skyrme Noemi de La Rocque Rodriguez Pablo Martins Musa Roberto Ierusalimschy Bruno Oliveira Silvestre1 1 Informatics Institute – Federal University of Goias (UFG) [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] Resumo. O suporte a` concorrenciaˆ pode ser considerado no projeto de uma linguagem de programac¸ao˜ ou provido por construc¸oes˜ inclu´ıdas, frequentemente por meio de bib- liotecas, a uma linguagem sem suporte ou com suporte limitado a funcionalidades de concorrencia.ˆ A escolha entre essas duas abordagens nao˜ e´ simples: linguagens com suporte nativo a` concorrenciaˆ oferecem eficienciaˆ e eleganciaˆ de sintaxe, enquanto bib- liotecas oferecem mais flexibilidade. Neste artigo discutimos uma terceira abordagem, dispon´ıvel em linguagens de script: embutir a concorrencia.ˆ Nos´ utilizamos a linguagem de programac¸ao˜ Lua e explicamos os mecanismos que ela oferece para suportar essa abordagem. Em seguida, utilizando dois sistemas concorrentes como exemplos, demon- stramos como esses mecanismos podem ser uteis´ na criac¸ao˜ de modelos leves de con- correncia.ˆ Palavras-chave: concorrencia,ˆ Lua, embutir, estender, scripting, threads, multithreading Abstract. -

Ruby Benchmark Suite Using Docker 949

Proceedings of the Federated Conference on DOI: 10.15439/2015F99 Computer Science and Information Systems pp. 947–952 ACSIS, Vol. 5 Ruby Benchmark Tool using Docker Richard Ludvigh, Tomáš Rebok Václav Tunka, Filip Nguyen Faculty of Informatics, Masaryk University Red Hat Czech, JBoss Middleware Botanická 68a, 60200, Brno, Czech Republic Purkynovaˇ 111, 61245 Brno, Czech Republic Email: [email protected], xrebok@fi.muni.cz Email: {vtunka,fnguyen}@redhat.com Abstract—The purpose of this paper is to introduce and on a baremetal and virtual server to provide results from both describe a new Ruby benchmarking tool. We will describe the environments. In section III-D, we describe both environments background of Ruby benchmarking and the advantages of the and their configuration in detail. new tool. The paper documents the benchmarking process as well as methods used to obtain results and run tests. To illustrate the The results we present are also available online. The results provided tool, results that were obtained by running a developed are in three main areas: benchmarking tool on existing and available official ruby bench- • MRI Versions overview - we have compared multiple marks are provided. These results document advantages in using MRI Ruby versions to determine the progress mainly in various Ruby compilers or Ruby implementations. memory usage as new MRI (2.2.0) has announced a new I. INTRODUCTION garbage collection algorithm. UBY IS A PURE OBJECT-ORIENTED interpreted lan- • A comparison of MRI compilers determined the differ- R guage. The language itself has three major implementa- ences in using different C compilers to compile Ruby tions: MRI written in C, JRuby written in Java, and Rubinius (2.2.0 used in benchmarks). -

Cnc-Python: Multicore Programming with High Productivity

CnC-Python: Multicore Programming with High Productivity Shams Imam and Vivek Sarkar Rice University fshams, [email protected] Abstract to write parallel programs, are faced with the unappeal- ing task of extracting parallelism from their applications. We introduce CnC-Python, an implementation of the The challenge then is how to make parallel programming Concurrent Collections (CnC) programming model for more accessible to such programmers. Python computations. Python has been gaining popu- In this paper, we introduce a Python-based imple- larity in multiple domains because of its expressiveness mentation of Intel’s Concurrent Collections (CnC) [10] and high productivity. However, exploiting multicore model which we call CnC-Python. CnC-Python allows parallelism in Python is comparatively tedious since it domain experts to express their application logic in sim- requires the use of low-level threads or multiprocessing ple terms using sequential Python code called steps. modules. CnC-Python, being implicitly parallel, avoids The domain experts also identify control and data de- the use of these low-level constructs, thereby enabling pendences in a simple declarative manner. Given these Python programmers to achieve task, data and pipeline declarative constraints, it is the responsibility of the com- parallelism in a declarative fashion while only being re- piler and a runtime to extract parallelism and perfor- quired to describe the program as a coordination graph mance from the application. CnC-Python programs are with serial Python code for individual steps. The CnC- also provably deterministic making it easier for program- Python runtime requires that Python objects communi- mers to debug their applications. To the best of our cated between steps be serializable (picklable), but im- knowledge, this is the first implementation of CnC in poses no restriction on the Python idioms used within an imperative language that guarantees isolation of steps the serial code. -

Advanced Programming

301AA - Advanced Programming Lecturer: Andrea Corradini [email protected] http://pages.di.unipi.it/corradini/ AP-28: Garbage collection, GIL, scripting Garbage collection in Python CPython manages memory with a reference counting + a mark&sweep cycle collector scheme • Reference counting: each object has a counter storing the number of references to it. When it becomes 0, memory can be reclaimed. • Pros: simple implementation, memory is reclaimed as soon as possible, no need to freeze execution passing control to a garbage collector • Cons: additional memory needed for each object; cyclic structures in garbage cannot be identified (thus the need of mark&sweep) 2 Handling reference counters • Updating the refcount of an object has to be done atomically • In case of multi-threading you need to synchronize all the times you modify refcounts, or else you can have wrong values • Synchronization primitives are quite expensive on contemporary hardware • Since almost every operation in CPython can cause a refcount to change somewhere, handling refcounts with some kind of synchronization would cause spending almost all the time on synchronization • As a consequence… 3 Concurrency in Python… 4 The Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) • The CPython interpreter assures that only one thread executes Python bytecode at a time, thanks to the Global Interpreter Lock • The current thread must hold the GIL before it can safely access Python objects • This simplifies the CPython implementation by making the object model (including critical built-in types such as dict) implicitly safe against concurrent access • Locking the entire interpreter makes it easier for the interpreter to be multi-threaded, at the expense of much of the parallelism afforded by multi-processor machines. -

Eliminating Global Interpreter Locks in Ruby Through Hardware Transactional Memory

Eliminating Global Interpreter Locks in Ruby through Hardware Transactional Memory Rei Odaira IBM Research – Tokyo, Jose G. Castanos IBM Research – Watson Research Center © 2013 IBM Corporation IBM Research – Tokyo Global Interpreter Locks in Scripting Languages Scripting languages (Ruby, Python, etc.) everywhere. Increasing demand on speed. Many existing projects for single-thread speed. – JIT compiler (Rubinius, ytljit, PyPy, Fiorano, etc.) – HPC Ruby Multi-thread speed restricted by global interpreter locks. – Only one thread can execute interpreter at one time. ☺No parallel programming needed in interpreter. ̓ No scalability on multi cores. 2 © 2013 IBM Corporation IBM Research – Tokyo Hardware Transactional Memory (HTM) Coming into the Market Improve performance by simply replacing locks with TM? Realize lower overhead than software TM by hardware. Sun Microsystems Rock Processor Blue Gene/Q Cancelled 2012 Intel Transactional zEC12 Synchronization 2012 eXtensions, 2013 3 © 2013 IBM Corporation IBM Research – Tokyo Our Goal What will the performance of real applications be if we replace GIL with HTM? – Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) What modifications and new techniques are needed? 4 © 2013 IBM Corporation IBM Research – Tokyo Our Goal What will the performance of real applications be if we replace GIL with HTM? – Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) What modifications and new techniques are needed? Eliminate GIL in Ruby through zEC12’s HTM Evaluate Ruby NAS Parallel Benchmarks zEC12 atomic { } 5 © 2013 IBM Corporation IBM Research – Tokyo Related Work Eliminate Python’s GIL with HTM ̓ Micro-benchmarks on non-cycle-accurate simulator [Riley et al. ,2006] ̓ Micro-benchmarks on cycle-accurate simulator [Blundell et al., 2010] ̓ Micro-benchmarks on Rock’s restricted HTM [Tabba, 2010] Eliminate Ruby and Python’s GILs with fine-grain locks – JRuby, IronRuby, Jython, IronPython, etc.