1 of 106 Natural Resource Inventory For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insect Survey of Four Longleaf Pine Preserves

A SURVEY OF THE MOTHS, BUTTERFLIES, AND GRASSHOPPERS OF FOUR NATURE CONSERVANCY PRESERVES IN SOUTHEASTERN NORTH CAROLINA Stephen P. Hall and Dale F. Schweitzer November 15, 1993 ABSTRACT Moths, butterflies, and grasshoppers were surveyed within four longleaf pine preserves owned by the North Carolina Nature Conservancy during the growing season of 1991 and 1992. Over 7,000 specimens (either collected or seen in the field) were identified, representing 512 different species and 28 families. Forty-one of these we consider to be distinctive of the two fire- maintained communities principally under investigation, the longleaf pine savannas and flatwoods. An additional 14 species we consider distinctive of the pocosins that occur in close association with the savannas and flatwoods. Twenty nine species appear to be rare enough to be included on the list of elements monitored by the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program (eight others in this category have been reported from one of these sites, the Green Swamp, but were not observed in this study). Two of the moths collected, Spartiniphaga carterae and Agrotis buchholzi, are currently candidates for federal listing as Threatened or Endangered species. Another species, Hemipachnobia s. subporphyrea, appears to be endemic to North Carolina and should also be considered for federal candidate status. With few exceptions, even the species that seem to be most closely associated with savannas and flatwoods show few direct defenses against fire, the primary force responsible for maintaining these communities. Instead, the majority of these insects probably survive within this region due to their ability to rapidly re-colonize recently burned areas from small, well-dispersed refugia. -

Newsletter of the Biological Survey of Canada

Newsletter of the Biological Survey of Canada Vol. 40(1) Summer 2021 The Newsletter of the BSC is published twice a year by the In this issue Biological Survey of Canada, an incorporated not-for-profit From the editor’s desk............2 group devoted to promoting biodiversity science in Canada. Membership..........................3 President’s report...................4 BSC Facebook & Twitter...........5 Reminder: 2021 AGM Contributing to the BSC The Annual General Meeting will be held on June 23, 2021 Newsletter............................5 Reminder: 2021 AGM..............6 Request for specimens: ........6 Feature Articles: Student Corner 1. City Nature Challenge Bioblitz Shawn Abraham: New Student 2021-The view from 53.5 °N, Liaison for the BSC..........................7 by Greg Pohl......................14 Mayflies (mainlyHexagenia sp., Ephemeroptera: Ephemeridae): an 2. Arthropod Survey at Fort Ellice, MB important food source for adult by Robert E. Wrigley & colleagues walleye in NW Ontario lakes, by A. ................................................18 Ricker-Held & D.Beresford................8 Project Updates New book on Staphylinids published Student Corner by J. Klimaszewski & colleagues......11 New Student Liaison: Assessment of Chironomidae (Dip- Shawn Abraham .............................7 tera) of Far Northern Ontario by A. Namayandeh & D. Beresford.......11 Mayflies (mainlyHexagenia sp., Ephemerop- New Project tera: Ephemeridae): an important food source Help GloWorm document the distribu- for adult walleye in NW Ontario lakes, tion & status of native earthworms in by A. Ricker-Held & D.Beresford................8 Canada, by H.Proctor & colleagues...12 Feature Articles 1. City Nature Challenge Bioblitz Tales from the Field: Take me to the River, by Todd Lawton ............................26 2021-The view from 53.5 °N, by Greg Pohl..............................14 2. -

2016 Connecticut Hunting & Trapping Guide

2016 CONNECTICUT HUNTING & TRAPPING Connecticut Department of VISIT OUR WEBSITE Energy & Environmental Protection www.ct.gov/deep/hunting MONARCH® BINOCULARS Built to satisfy the incredible needs of today’s serious outdoorsmen & women, MONARCH binoculars not only bestow the latest in optical innovation upon the passions of its owner, but offer dynamic handling & rugged performance for virtually any hunting situation. MONARCH® RIFLESCOPES Bright, clear, precise, rugged - just a few of the attributes knowledgeable hunters commonly use to describe Nikon® riflescopes. Nikon® is determined to bring hunters, shooters & sportsmen a wide selection of the best hunting optics money can buy, while at the same time creating revolutionary capabilities for the serious hunter. Present this coupon for $25 OFF your in-store purchase of $150 or more! Valid through December 31, 2016 Not valid online, on gift cards, non-merchandise items, licenses, previous purchases or special orders. Excludes NIKON, CARHARTT, UGG, THE NORTH FACE, PATAGONIA, MERRELL, DANSKO, AVET REELS, SHIMANO, G.LOOMIS & SAGE items. Cannot be combined with any other offer. No copies. One per customer. No cash value. CT2016 Kittery Trading Post / Rte 1 Kittery, ME / Mon-Sat 9-9, Sun 10-6 / 888-587-6246 / ktp.com / ktpguns.com 2016 CONNECTICUT HUNTING & TRAPPING Contents Licenses, Permits & Tags ............................................................ 8–10 Firearms Hunting Licenses Small Game and Deer Archery Deer and Turkey Permits Pheasant Tags Waterfowl Stamps Hunter Education Requirements Lost License Handicapped License Hunting Laws & Regulations ..................................................... 12–15 BE BEAR AWARE, page 6 Definitions Learn what you should do if you encounter bears in the outdoors or around Closed Seasons your home. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date. -

Keeping Paradise Unpaved in the Trenches of Land Preservation

CONNECTICUT Woodlands CFPA’S LEGISLATIVE for INSIDE AGENDA 2014 KEEPING PARADISE UNPAVED IN THE TRENCHES OF LAND PRESERVATION The Magazine of the Connecticut Forest & Park Association Spring 2014 Volume 79 No. 1 The ConnectiCuT ForesT & Park assoCiaTion, inC. OFFICERS PRESIDENT, ERIC LUKINGBEAL, Granby VICE-PRESIDENT, WILLIAM D. BRECK, Killingworth VICE-PRESIDENT, GEOFFREY MEISSNER, Plantsville VICE-PRESIDENT, DAVID PLATT, Higganum VICE-PRESIDENT, STARR SAYRES, East Haddam TREASURER, JAMES W. DOMBRAUSKAS, New Hartford SECRETARY, ERIC HAMMERLING, West Hartford FORESTER, THOMAS J. DEGNAN, JR., East Haddam DIRECTORS RUSSELL BRENNEMAN, Westport ROBERT BUTTERWORTH, Deep River STARLING W. CHILDS, Norfolk RUTH CUTLER, Ashford THOMAS J. DEGNAN, JR., East Haddam CAROLINE DRISCOLL, New London ASTRID T. HANZALEK, Suffield DAVID LAURETTI, Bloomfield JEFFREY BRADLEY MICHAEL LECOURS, Farmington This pond lies in a state park few know about. See page 10. DAVID K. LEFF, Collinsville MIRANDA LINSKY, Middletown SCOTT LIVINGSTON, Bolton JEFF LOUREIRO, Canton LAUREN L. McGREGOR, Hamden JEFFREY O’DONNELL, Bristol Connecting People to the Land Annual Membership RICHARD WHITEHOUSE, Glastonbury Our mission: The Connecticut Forest & Park Individual $ 35 HONORARY DIRECTORS Association protects forests, parks, walking Family $ 50 GORDON L. ANDERSON, St. Johns, FL trails and open spaces for future generations by HARROL W. BAKER, JR., Bolton connecting people to the land. CFPA directly Supporting $ 100 RICHARD A. BAUERFELD, Redding involves individuals and families, educators, GEORGE M. CAMP, Middletown Benefactor $ 250 ANN M. CUDDY, Ashland, OR community leaders and volunteers to enhance PRUDENCE P. CUTLER, Farmington and defend Connecticut’s rich natural heritage. SAMUEL G. DODD, North Andover, MA CFPA is a private, non-profit organization that Life Membership $ 2500 JOHN E. -

Rattlesnake Mountain Farmington CT

This Mountain Hike In Connecticut Leads To Something Awesome Looking for a mountain hike in Connecticut that’s truly unique? Then look no further! At the top of this mountain is a hidden site, unknown by many Connecticut residents. But a little piece of folk history is waiting to be rediscovered by you. So let’s get going! Rattlesnake Mountain in Farmington is a 2.3-mile hike off of Route 6. Part of the Metacomet Ridge, this short trail can be a little taxing for beginners, but it's totally worth it! Be prepared to catch some fantastic sights atop this scenic vista as you explore the rare plants and traprock ridges. An increasing number of locals have begun using the ridges here for rock climbing. They may look for intimidating, but they make for great exercise. Not to mention you'd be climbing volcanic rock. At 750 feet high and 500 feet above the Farmington River Valley, there's no shortage of views. But the coolest thing atop this mountain isn't the sight. It's Will Warren's Den! This boulder rock cave is a local historic site that will leave you breathless. Who knew Connecticut had caves quite like this! 1 The plaque affixed to the cave reads "Said Warren, according to legend, after being flogged for not going to church, tried to burn the village of Farmington. He was pursued into the mountains, where some Indian squaws hid him in this cave." It may not look like much from the outside, but the inside is a cool oasis. -

Johnsons Announce Gift of 71-Acre Conservation Easement At

G RANBY EWSLETTER Land Trust N Preserving Granby’s Natural Heritage www.granbylandtrust.org C PO Box 23 C Granby, Connecticut 06035 C Volume 5 Johnsons Announce Gift of 71-Acre Conservation Easement at Annual Meeting he unusually warm and sunny late October Tday suggested that this would be a special Land Trust Annual Meeting. It was in many ways. With fall’s full colors on parade, almost 100 land trust members gathered on October 21st and were treated to a walk through one of Granby’s most beautiful properties – Paula and Whitey Johnson’s 90-acre parcel on Simsbury Road in West Granby – followed by an old-fashioned outdoor picnic at the Johnson’s house. It was a family affair all day. On the walk The Land Trust led by Whitey Johnson, kids ran Whitey Johnson talks about his property and its history thanks Paula ahead of the adults during the Annual Meeting Hike in October. and Whitey through the rolling fields, by the solid old stonewalls and into the Johnson for their Johnson’s woods which are bounded by the Land Trust Receives Three commitment and McLean Game Refuge. After the walk, every- Conservation Easements in 2007 one gathered together and the annual meeting • The Johnson Family - 71 acres dedication to was called to order. During the meeting, the • The Werner Family - 40 acres (see pg. 14) Granby and the Johnsons announced that they intended to • The Brown Family - 10+ acres (see pg. 7) give the Land Trust a conservation easement legacy they have over 71-acres of this spectacular land, forever built for future preserving it as open space. -

Appendix 1. Specimens Examined

Knapp et al. – Appendix 1 – Morelloid Clade in North and Central America and the Caribbean -1 Appendix 1. Specimens examined We list here in traditional format all specimens examined for this treatment from North and Central America and the Caribbean. Countries, major divisions within them (when known), and collectors (by surname) are listed in alphabetic order. 1. Solanum americanum Mill. ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA. Antigua: SW, Blubber Valley, Blubber Valley, 26 Sep 1937, Box, H.E. 1107 (BM, MO); sin. loc. [ex Herb. Hooker], Nicholson, D. s.n. (K); Barbuda: S.E. side of The Lagoon, 16 May 1937, Box, H.E. 649 (BM). BAHAMAS. Man O'War Cay, Abaco region, 8 Dec 1904, Brace, L.J.K. 1580 (F); Great Ragged Island, 24 Dec 1907, Wilson, P. 7832 (K). Andros Island: Conch Sound, 8 May 1890, Northrop, J.I. & Northrop, A.R. 557 (K). Eleuthera: North Eleuthera Airport, Low coppice and disturbed area around terminal and landing strip, 15 Dec 1979, Wunderlin, R.P. et al. 8418 (MO). Inagua: Great Inagua, 12 Mar 1890, Hitchcock, A.S. s.n. (MO); sin. loc, 3 Dec 1890, Hitchcock, A.S. s.n. (F). New Providence: sin. loc, 18 Mar 1878, Brace, L.J.K. 518 (K); Nassau, Union St, 20 Feb 1905, Wight, A.E. 111 (K); Grantstown, 28 May 1909, Wilson, P. 8213 (K). BARBADOS. Moucrieffe (?), St John, Near boiling house, Apr 1940, Goodwing, H.B. 197 (BM). BELIZE. carretera a Belmopan, 1 May 1982, Ramamoorthy, T.P. et al. 3593 (MEXU). Belize: Belize Municipal Airstrip near St. Johns College, Belize City, 21 Feb 1970, Dieckman, L. -

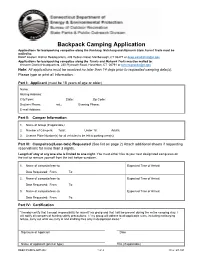

Backpacking Camping Application

Backpack Camping Application Applications for backpacking campsites along the Pachaug, Natchaug and Nipmuck State Forest Trails must be mailed to: DEEP Eastern District Headquarters, 209 Hebron Road, Marlborough, CT 06477 or [email protected] Applications for backpacking campsites along the Tunxis and Mohawk Trails must be mailed to: Western District Headquarters, 230 Plymouth Road, Harwinton, CT 06791 or [email protected] Note: All applications must be received no later than 14 days prior to requested camping date(s). Please type or print all information. Part I: Applicant (must be 18 years of age or older) Name: Mailing Address: City/Town: State: Zip Code: Daytime Phone: ext.: Evening Phone: E-mail Address: Part II: Camper Information 1. Name of Group (If applicable): 2. Number of Campers: Total: Under 18: Adults: 3. License Plate Number(s) for all vehicles to be left in parking area(s): Part III: Campsite(s)/Lean-to(s) Requested (See list on page 2) Attach additional sheets if requesting reservations for more than 3 nights. Length of stay at any one site is limited to one night. You must either hike to your next designated camp area on the trail or remove yourself from the trail before sundown. 1. Name of campsite/lean-to: Expected Time of Arrival: Date Requested: From: To: 2. Name of campsite/lean-to: Expected Time of Arrival: Date Requested: From: To: 3. Name of campsite/lean-to: Expected Time of Arrival: Date Requested: From: To: Part IV: Certification “I hereby certify that I accept responsibility for myself/ my group and that I will be present during the entire camping stay. -

Block Reports

MATRIX SITE: 1 RANK: MY NAME: Kezar River SUBSECTION: 221Al Sebago-Ossipee Hills and Plains STATE/S: ME collected during potential matrix site meetings, Summer 1999 COMMENTS: Aquatic features: kezar river watershed and gorgeassumption is good quality Old growth: unknown General comments/rank: maybe-yes, maybe (because of lack of eo’s) Logging history: yes, 3rd growth Landscape assessment: white mountian national forest bordering on north. East looks Other comments: seasonal roads and homes, good. Ownership/ management: 900 state land, small private holdings Road density: low, dirt with trees creating canopy Boundary: Unique features: gorge, Cover class review: 94% natural cover Ecological features, floating keetle hole bog.northern hard wood EO's, Expected Communities: SIZE: Total acreage of the matrix site: 35,645 LANDCOVER SUMMARY: 94 % Core acreage of the matrix site: 27,552 Natural Cover: Percent Total acreage of the matrix site: 35,645 Open Water: 2 Core acreage of the matrix site: 27,552 Transitional Barren: 0 % Core acreage of the matrix site: 77 Deciduous Forest: 41 % Core acreage in natural cover: 96 Evergreen Forest: 18 % Core acreage in non- natural cover: 4 Mixed Forest: 31 Forested Wetland: 1 (Core acreage = > 200m from major road or airport and >100m from local Emergent Herbaceous Wetland: 2 roads, railroads and utility lines) Deciduous shrubland: 0 Bare rock sand: 0 TOTAL: 94 INTERNAL LAND BLOCKS OVER 5k: 37 %Non-Natural Cover: 6 % Average acreage of land blocks within the matrix site: 1,024 Percent Maximum acreage of any -

The Pease Family Gives 58 Acres to The

G RANBY EWSLETTER Land Trust N Preserving Granby’s Natural Heritage www.granbylandtrust.org C PO Box 23 C Granby, Connecticut 06035 C Fall 2014 Granby Land Trust The Pease Family Gives Achieves National 58 Acres to the GLT Accreditation! We thank YOU for hen Marty and Sarah Pease to downhill ski not at a ski resort, your support. Wwere little girls, they had but on a steep, 50-foot long hill See page 3 for full article. the luxury of living on a piece of in the woods behind their house. property that was so varied in its They learned to ice skate not at a landscape that they learned how rink, but on their very own pond. continued on page 4 Al and Helen Wilke Donate 39-Acre Conservation Easement f you are lucky enough to be invited to Iwalk the trails on Al and Helen Wilke’s property, you will begin to understand just how much they love the land upon which they live. The Wilkes have made their en- tire 45-acre property a labor of love, with groomed trails and sturdy bridges and log benches that beckon you to sit and look and listen and enjoy the beautiful, peace- ful world around you. Near the house are manicured gardens, man-made ponds, MOOSEHORN BROOK continued on page 6 WILKE PROPERTY Photo: Peter Dinella 5 If you would like to explore making a land gift to the Granby Land Trust, please contact a GLT Board Member. 5 Board Members Granby Land Trust Officers Rick Orluk, President 653-7095 Dear Friends, - Rod Dimock, Vice President At this year’s Annual Meeting, Trish and I were awarded the Mary Edwards Friend of the Land Trust Award. -

Complete Event Quick List 1

All Events - 2013 Connecticut Trails Day Weekend (June 1 & 2, 2013) For full event details, see the printed 2013 Connecticut Trails Day Weekend booklet or the online version at www.ctwoodlands.org/CT-TrailsDayWeekend2013. Events denoted with an asterisk* below are events listed in the online supplement at www.ctwoodlands.org/CT- TrailsDayWeekend2013-SupplementListings. Also check the supplement page for event updates and corrections. Events marked with the Facebook icon in the booklet will be posting any updates on CFPA's Facebook page by the morning of their scheduled event. www.facebook.com/CTForestandParkAssociation ANDOVER see BOLTON 1. ANSONIA Educational Walk. Saturday, June 1. 9:00 AM to 11:00 AM. Ansonia Nature and Recreation Center/Raptor Woods Trail. 2. ASHFORD Hike. Sunday, June 2. 1:30 PM to 4:30 PM. Yale Myers Forest/Nipmuck Trail. 3. AVON Educational Walk. Saturday, June 1. 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM. Fisher Meadows. AVON see FARMINGTON 4. BARKHAMSTED (PLEASANT VALLEY) Educational Walk. Saturday, June 1. 9:00 AM to 12:30 PM. American Legion State Forest/Turkey Vulture Ledge Trail. 5. BARKHAMSTED - CANTON Fitness Walk. Sunday, June 2. 8:00 AM to 1:00 PM. Peoples State Forest. BARKHAMSTED see HARTLAND 6. BEACON FALLS Bike. Saturday, June 1. 2:30 PM to 4:30 PM. Matthies Park. BEACON FALLS see BETHANY 7. BERLIN Hike. Saturday, June 1. 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM. Blue Hills Conservation Area/Metacomet Trail. Complete Event Quick List 1 8. BERLIN Hike. Saturday, June 1. 9:00 AM to 11:30 AM. Hatchery Brook Conservation Area.