Information Maps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of the Infographic

EVOLUTION OF THE INFOGRAPHIC: Then, now, and future-now. EVOLUTION People have been using images and data to tell stories for ages—long before the days of the Internet, smartphones, and Excel. In fact, the history of infographics pre-dates the web by more than 30,000 years with the earliest forms of these visuals being cave paintings that helped early humans find food, resources, and shelter. But as technology has advanced, so has our ability to tell meaningful stories. Here’s a look into the evolution of modern infographics—where they’ve been, how they’ve evolved, and where they’re headed. Then: Printed, static infographics The 20th Century introduced the infographic—a staple for how we communicate, visualize, and share information today. Early on, these print graphics married illustration and data to communicate information in a revolutionary way. ADVANTAGE Design elements enable people to quickly absorb information previously confined to long paragraphs of text. LIMITATION Static infographics didn’t allow for deeper dives into the data to explore granularities. Hoping to drill down for more detail or context? Tough luck—what you see is what you get. Source: http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2012-01/16/painting- by-numbers-at-london-transport-museum INFOGRAPHICS THROUGH THE AGES DOMO 03 Now: Web-based, interactive infographics While the first wave of modern infographics made complex data more consumable, web-based, interactive infographics made data more explorable. These are everywhere today. ADVANTAGE Everyone looking to make data an asset, from executives to graphic designers, are now building interactive data stories that deliver additional context and value. -

DESIGN Principles & Practices: an International Journal

DESIGN Principles & Practices: An International Journal Volume 3, Number 1 A Computational Investigation into the Fractal Dimensions of the Architecture of Kazuyo Sejima Michael J. Ostwald, Josephine Vaughan and Stephan K. Chalup www.design-journal.com DESIGN PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.Design-Journal.com First published in 2009 in Melbourne, Australia by Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd www.CommonGroundPublishing.com. © 2009 (individual papers), the author(s) © 2009 (selection and editorial matter) Common Ground Authors are responsible for the accuracy of citations, quotations, diagrams, tables and maps. All rights reserved. Apart from fair use for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act (Australia), no part of this work may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please contact <[email protected]>. ISSN: 1833-1874 Publisher Site: http://www.Design-Journal.com DESIGN PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL is peer- reviewed, supported by rigorous processes of criterion-referenced article ranking and qualitative commentary, ensuring that only intellectual work of the greatest substance and highest significance is published. Typeset in Common Ground Markup Language using CGCreator multichannel typesetting system http://www.commongroundpublishing.com/software/ A Computational Investigation into the Fractal Dimensions of the Architecture of Kazuyo Sejima Michael J. Ostwald, The University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia Josephine Vaughan, The University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia Stephan K. Chalup, The University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia Abstract: In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s a range of approaches to using fractal geometry for the design and analysis of the built environment were developed. -

Digital Mapping & Spatial Analysis

Digital Mapping & Spatial Analysis Zach Silvia Graduate Community of Learning Rachel Starry April 17, 2018 Andrew Tharler Workshop Agenda 1. Visualizing Spatial Data (Andrew) 2. Storytelling with Maps (Rachel) 3. Archaeological Application of GIS (Zach) CARTO ● Map, Interact, Analyze ● Example 1: Bryn Mawr dining options ● Example 2: Carpenter Carrel Project ● Example 3: Terracotta Altars from Morgantina Leaflet: A JavaScript Library http://leafletjs.com Storytelling with maps #1: OdysseyJS (CartoDB) Platform Germany’s way through the World Cup 2014 Tutorial Storytelling with maps #2: Story Maps (ArcGIS) Platform Indiana Limestone (example 1) Ancient Wonders (example 2) Mapping Spatial Data with ArcGIS - Mapping in GIS Basics - Archaeological Applications - Topographic Applications Mapping Spatial Data with ArcGIS What is GIS - Geographic Information System? A geographic information system (GIS) is a framework for gathering, managing, and analyzing data. Rooted in the science of geography, GIS integrates many types of data. It analyzes spatial location and organizes layers of information into visualizations using maps and 3D scenes. With this unique capability, GIS reveals deeper insights into spatial data, such as patterns, relationships, and situations - helping users make smarter decisions. - ESRI GIS dictionary. - ArcGIS by ESRI - industry standard, expensive, intuitive functionality, PC - Q-GIS - open source, industry standard, less than intuitive, Mac and PC - GRASS - developed by the US military, open source - AutoDESK - counterpart to AutoCAD for topography Types of Spatial Data in ArcGIS: Basics Every feature on the planet has its own unique latitude and longitude coordinates: Houses, trees, streets, archaeological finds, you! How do we collect this information? - Remote Sensing: Aerial photography, satellite imaging, LIDAR - On-site Observation: total station data, ground penetrating radar, GPS Types of Spatial Data in ArcGIS: Basics Raster vs. -

Techniques for Spatial Analysis and Visualization of Benthic Mapping Data: Final Report

Techniques for spatial analysis and visualization of benthic mapping data: final report Item Type monograph Authors Andrews, Brian Publisher NOAA/National Ocean Service/Coastal Services Center Download date 29/09/2021 07:34:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/20024 TECHNIQUES FOR SPATIAL ANALYSIS AND VISUALIZATION OF BENTHIC MAPPING DATA FINAL REPORT April 2003 SAIC Report No. 623 Prepared for: NOAA Coastal Services Center 2234 South Hobson Avenue Charleston SC 29405-2413 Prepared by: Brian Andrews Science Applications International Corporation 221 Third Street Newport, RI 02840 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................1 1.1 Benthic Mapping Applications..........................................................................1 1.2 Remote Sensing Platforms for Benthic Habitat Mapping ..........................................2 2.0 SPATIAL DATA MODELS AND GIS CONCEPTS ................................................3 2.1 Vector Data Model .......................................................................................3 2.2 Raster Data Model........................................................................................3 3.0 CONSIDERATIONS FOR EFFECTIVE BENTHIC HABITAT ANALYSIS AND VISUALIZATION .........................................................................................4 3.1 Spatial Scale ...............................................................................................4 3.2 Habitat Scale...............................................................................................4 -

Business Analyst: Using Your Own Data with Enrichment & Infographics

Business Analyst: Using Your Own Data with Enrichment & Infographics Steven Boyd Daniel Stauning Tony Howser Wednesday, July 11, 2018 2:30 PM – 3:15 PM • Business Analysis solution built on ArcGIS ArcGIS Business • Connected Apps, Tools, Reports & Data Analyst • Workflows to solve business problems Sites Customers Markets ArcGIS Business Analyst Web App Mobile App Desktop/Pro App …powered by ArcGIS Enterprise / ArcGIS Online “Custom” Data in Business Analyst • Your organization’s own data • Third-party data • Any data that you want to use alongside Esri’s data in mapping, reporting, Infographics, and more “Custom” Data in Business Analyst • Your organization’s own data • Third-party data • Any data that you want to use alongside Esri’s data in mapping, reporting, Infographics, and more “Custom” Data in Business Analyst • Your organization’s own data • Third-party data • Any data that you want to use alongside Esri’s data in mapping, reporting, Infographics, and more “Custom”“Custom” Data Data in Business Analyst in Business Analyst • Your organization’s own data • Your• Third organization’s-party data own data• Data that you want to use alongside Esri’s data in mapping, reporting, Infographics, and more • Third-party data • Any data that you want to use alongside Esri’s data in mapping, reporting, Infographics, and more Custom Data in Apps, Reports, and Infographics Daniel Stauning Steven Boyd Please Take Our Survey on the App Download the Esri Events Select the session Scroll down to find the Complete answers app and find your event you attended feedback section and select “Submit” See Us Here WORKSHOP LOCATION TIME FRAME ArcGIS Business Analyst: Wednesday, July 11 SDCC – Room 30E An Introduction (2nd offering) 4:00 PM – 5:00 PM Esri's US Demographics: Thursday, July 12 SDCC – Room 8 What's New 2:30 PM – 3:30 PM Chat with members of the Business Analyst team at the Spatial Analysis Island at the UC Expo . -

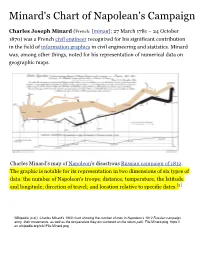

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign

Minard's Chart of Napolean's Campaign Charles Joseph Minard (French: [minaʁ]; 27 March 1781 – 24 October 1870) was a French civil engineer recognized for his significant contribution in the field of information graphics in civil engineering and statistics. Minard was, among other things, noted for his representation of numerical data on geographic maps. Charles Minard's map of Napoleon's disastrous Russian campaign of 1812. The graphic is notable for its representation in two dimensions of six types of data: the number of Napoleon's troops; distance; temperature; the latitude and longitude; direction of travel; and location relative to specific dates.[2] Wikipedia (n.d.). Charles Minard's 1869 chart showing the number of men in Napoleon’s 1812 Russian campaign army, their movements, as well as the temperature they encountered on the return path. File:Minard.png. https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Minard.png The original description in French accompanying the map translated to English:[3] Drawn by Mr. Minard, Inspector General of Bridges and Roads in retirement. Paris, 20 November 1869. The numbers of men present are represented by the widths of the colored zones in a rate of one millimeter for ten thousand men; these are also written beside the zones. Red designates men moving into Russia, black those on retreat. — The informations used for drawing the map were taken from the works of Messrs. Thiers, de Ségur, de Fezensac, de Chambray and the unpublished diary of Jacob, pharmacist of the Army since 28 October. Recognition Modern information -

11.205 : Intro to Spatial Analysis

11.205 : INTRO TO SPATIAL ANALYSIS INSTRUCTOR : SARAH WILLIAMS ([email protected]) LAB INSTRUCTORS : Melissa Yvonne Chinchilla ([email protected] ), Mike Foster ([email protected]), Michael Thomas Wilson ([email protected]) TEACHING ASSISTANTS: Elizabeth Joanna Irvin ([email protected])& Halley Brunsteter Reeves ([email protected]) LECTURE : Monday and Wednesday 2:30- 4pm, Room 9-354 LABS : (All in Room W31-301) Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursdays 5-7pm – To Be Assigned Class Description: Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are tools for managing data about where features are (geographic coordinate data) and what they are like (attribute data), and for providing the ability to query, manipulate, and analyze those data. Because GIS allows one to represent social and environmental data as a map, it has become an important analysis tool used across a variety of fields including: planning, architecture, engineering, public health, environmental science, economics, epidemiology, and business. GIS has become an important political instrument allowing communities and regions to graphically tell their story. GIS is a powerful tool, and this course is meant to introduce students to the basics. Because GIS can be applied to many research fields, this class is meant to give you an understanding of its possibilities. Learning Through Practice: The class will focus on teaching through practical example. All the course exercises will focus on a relationship with the Bronx River Alliance, a local advocacy group for the Bronx River. Exercises will focus on the Bronx River Alliance’s real-world needs, in order to give students a better understanding of how GIS is applied to planning situations. -

Modeling Fractal Structure of Systems of Cities Using Spatial Correlation Function

Modeling Fractal Structure of Systems of Cities Using Spatial Correlation Function Yanguang Chen1, Shiguo Jiang2 (1. Department of Geography, Peking University, Beijing 100871, PRC. E-mail: [email protected]; 2. Department of Geography, The Ohio State University, USA. Email: [email protected].) Abstract: This paper proposes a new method to analyze the spatial structure of urban systems using ideas from fractals. Regarding a system of cities as a set of “particles” distributed randomly on a triangular lattice, we construct a spatial correlation function of cities. Suppose that the spatial correlation follows the power law. It can be proved that the correlation exponent is the second order generalized dimension. The spatial correlation model is applied to the system of cities in China. The results show that the Chinese urban system can be described by the correlation dimension ranging from 1.3 to 1.6. The fractality of self-organized network of cities in both the conventional geographic space and the “time” space is revealed with the empirical evidence. The spatial correlation analysis is significant in that it is applicable to both large and small sizes of samples and can be used to link different fractal dimensions in urban study, including box dimension and radial dimension. 1 Introduction The evolution of cities as systems and systems of cities bears some similarity. In theory, a system of cites follows the same spatial scaling laws with a city as a system. The great majority of fractal models and methods for urban form and structure are in fact available for systems of cities. -

Capítulo 1 Análise De Sentimentos Utilizando Técnicas De Classificação Multiclasse

XII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação De 17 a 20 de maio de 2016 Florianópolis – SC Tópicos em Sistemas de Informação: Minicursos SBSI 2016 Sociedade Brasileira de Computação – SBC Organizadores Clodis Boscarioli Ronaldo dos Santos Mello Frank Augusto Siqueira Patrícia Vilain Realização INE/UFSC – Departamento de Informática e Estatística/ Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Promoção Sociedade Brasileira de Computação – SBC Patrocínio Institucional CAPES – Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior CNPq - Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico FAPESC - Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina Catalogação na fonte pela Biblioteca Universitária da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina S612a Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação (12. : 2016 : Florianópolis, SC) Anais [do] XII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação [recurso eletrônico] / Tópicos em Sistemas de Informação: Minicursos SBSI 2016 ; organizadores Clodis Boscarioli ; realização Departamento de Informática e Estatística/ Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina ; promoção Sociedade Brasileira de Computação (SBC). Florianópolis : UFSC/Departamento de Informática e Estatística, 2016. 1 e-book Minicursos SBSI 2016: Tópicos em Sistemas de Informação Disponível em: http://sbsi2016.ufsc.br/anais/ Evento realizado em Florianópolis de 17 a 20 de maio de 2016. ISBN 978-85-7669-317-8 1. Sistemas de recuperação da informação Congressos. 2. Tecnologia Serviços de informação Congressos. 3. Internet na administração pública Congressos. I. Boscarioli, Clodis. II. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Departamento de Informática e Estatística. III. Sociedade Brasileira de Computação. IV. Título. CDU: 004.65 Prefácio Dentre as atividades de Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas de Informação (SBSI) a discussão de temas atuais sobre pesquisa e ensino, e também sua relação com a indústria, é sempre oportunizada. -

Avian Flu Case Study with Nspace and Geotime

Avian Flu Case Study with nSpace and GeoTime Pascale Proulx, Sumeet Tandon, Adam Bodnar, David Schroh, Robert Harper, and William Wright* Oculus Info Inc. ABSTRACT 1.1 nSpace - A Unified Analytical Workspace GeoTime and nSpace are new analysis tools that provide nSpace combines several interactive visualization techniques to innovative visual analytic capabilities. This paper uses an create a unified workspace that supports the analytic process. One epidemiology analysis scenario to illustrate and discuss these new technique, called TRIST (The Rapid Information Scanning Tool), investigative methods and techniques. In addition, this case study uses multiple linked views to support rapid and efficient scanning is an exploration and demonstration of the analytical synergy and triaging of thousands of search results in one display. The achieved by combining GeoTime’s geo-temporal analysis other technique, called the Sandbox, supports both ad-hoc and capabilities, with the rapid information triage, scanning and sense- formal sense making within a flexible free thinking environment. making provided by nSpace. Additionally, nSpace makes use of multiple advanced A fictional analyst works through the scenario from the initial computational linguistic functions using a web services interface brainstorming through to a final collaboration and report. With the and protocol [6, 3]. efficient knowledge acquisition and insights into large amounts of documents, there is more time for the analyst to reason about the 1.1.1 TRIST problem and imagine ways to mitigate threats. The use of both nSpace and GeoTime initiated a synergistic exchange of ideas, where hypotheses generated in either software tool could be cross- TRIST, as seen in Figure 1, uses advanced information retrieval referenced, refuted, and supported by the other tool. -

Concept Mapping, Mind Mapping and Argument Mapping: What Are the Differences and Do They Matter?

Concept Mapping, Mind Mapping and Argument Mapping: What are the Differences and Do They Matter? W. Martin Davies The University of Melbourne, Australia [email protected] Abstract: In recent years, academics and educators have begun to use software mapping tools for a number of education-related purposes. Typically, the tools are used to help impart critical and analytical skills to students, to enable students to see relationships between concepts, and also as a method of assessment. The common feature of all these tools is the use of diagrammatic relationships of various kinds in preference to written or verbal descriptions. Pictures and structured diagrams are thought to be more comprehensible than just words, and a clearer way to illustrate understanding of complex topics. Variants of these tools are available under different names: “concept mapping”, “mind mapping” and “argument mapping”. Sometimes these terms are used synonymously. However, as this paper will demonstrate, there are clear differences in each of these mapping tools. This paper offers an outline of the various types of tool available and their advantages and disadvantages. It argues that the choice of mapping tool largely depends on the purpose or aim for which the tool is used and that the tools may well be converging to offer educators as yet unrealised and potentially complementary functions. Keywords: Concept mapping, mind mapping, computer-aided argument mapping, critical thinking, argument, inference-making, knowledge mapping. 1. INTRODUCTION The era of computer-aided mapping tools is well and truly here. In the past five to ten years, a variety of software packages have been developed that enable the visual display of information, concepts and relations between ideas. -

To Draw a Tree

To Draw a Tree Pat Hanrahan Computer Science Department Stanford University Motivation Hierarchies File systems and web sites Organization charts Categorical classifications Similiarity and clustering Branching processes Genealogy and lineages Phylogenetic trees Decision processes Indices or search trees Decision trees Tournaments Page 1 Tree Drawing Simple Tree Drawing Preorder or inorder traversal Page 2 Rheingold-Tilford Algorithm Information Visualization Page 3 Tree Representations Most Common … Page 4 Tournaments! Page 5 Second Most Common … Lineages Page 6 http://www.royal.gov.uk/history/trees.htm Page 7 Demonstration Saito-Sederberg Genealogy Viewer C. Elegans Cell Lineage [Sulston] Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 Evolutionary Trees [Haeckel] Page 12 Page 13 [Agassiz, 1883] 1989 Page 14 Chapple and Garofolo, In Tufte [Furbringer] Page 15 [Simpson]] [Gould] Page 16 Tree of Life [Haeckel] [Tufte] Page 17 Janvier, 1812 “Graphical Excellence is nearly always multivariate” Edward Tufte Page 18 Phenograms to Cladograms GeneBase Page 19 http://www.gwu.edu/~clade/spiders/peet.htm Page 20 Page 21 The Shape of Trees Page 22 Patterns of Evolution Page 23 Hierachical Databases Stolte and Hanrahan, Polaris, InfoVis 2000 Page 24 Generalization • Aggregation • Simplification • Filtering Abstraction Hierarchies Datacubes Star and Snowflake Schemes Page 25 Memory & Code Cache misses for a procedure for 10 million cycles White = not run Grey = no misses Red = # misses y-dimension is source code x-dimension is cycles (time) Memory & Code zooming on y zooms from fileprocedurelineassembly code zooming on x increases time resolution down to one cycle per bar Page 26 Themes Cognitive Principles for Design Congruence Principle: The structure and content of the external representation should correspond to the desired structure and content of the internal representation.