Forced Rhubarb in West Yorkshire C.1852-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDROYD PLACE, FARSLEY, PUDSEY, LS28 5JQ Guide Price

EDROYD PLACE, FARSLEY, PUDSEY, LS28 5JQ Guide Price £137,000 2 Bedroom House EPC Rating: E Offered for sale with no onward chain we are pleased to offer this character filled two bedroom Victorian stone built end terrace home hidden away on Edroyd Place, Farsley. Having its own south facing terraced garden this attractive double fronted cottage with accommodation comprising entrance hall, large kitchen/diner, living room, landing leading to two bedroom bedrooms and family bathroom. The cottage also benefits from double glazing, gas central heating system, on street parking, cellar and south facing sun terrace. Farsley is a popular Village which has fantastic commuting , either by private or public transport. The A6120 and A647 are both on hand and provide major links to the motorway networks. Just a short distance away is the popular Owlcotes Centre at Pudsey offering a Marks & Spencer store, Asda superstore, and there is a train station adjacent. In addition, the bus services are frequent from the village, getting you into Leeds & Bradford City centres. There is a good selection of shops, pubs and eateries in Farsley and schools are also popular. The neighbouring villages of Pudsey and Horsforth are only a short distance away and also offer a comprehensive range of facilities. ACCOMMODATION ENTRANCE HALL Giving access to kitchen/diner and living room. Stairs to the first floor landing. LOUNGE Television and telephone point. Dado rail and radiator. Double glazed window to the front. Feature gas fire and surround. DINING KITCHEN Fitted with a range of base and wall units with work surfaces over. -

Seniors in Touch

July 2018 Vol. 10 Issue 7 Seniors In Touch “It means so much to stay in touch” A Sentimental Centennial Special Days in July by Allison Brunette 1 International Joke Day When you need advice, who 2 Build A Scarecrow Day better to listen to than someone older and wiser? No matter your 2 I Forgot Day age — old or young — time al- ways brings a unique perspective 2 World UFO Day on the way we should have done things. 5 Work-a-holic Day In an endearing video, CBC Ra- 10 Teddy Bear Picnic Day dio asked people of all ages — as young as 7 and as old as 93 — 11 Cheer up the Lonely Day to share their best piece of ad- vice for a person just a year 13 Fool's Paradise Day younger. 14 Bastille Day The brutally honest responses were both charming and wise, 15 Cow Appreciation Day covering everything from love and relationships, to money and 16 Fresh Spinach Day career, to finding your confi- Edgar Kuhlow admiring his cake. dence. 19 National Raspberry Pie Day Here are just a few: - Stop caring so much about what people think. They’re not thinking 20 Moon Day about you at all. Sincerely, a 47-year-old - A midlife crisis does not look good. Sincerely, a 48-year-old 22 Hammock Day - Always tell the truth (except in your online dating profile). Sincerely, a 51-year-old 22 Rat Catcher's Day - Spend all your money, or your kids will do it for you. Sincerely, an 85- 23 National Hot Dog Day year-old And the very best.. -

WEST Ridlng YORKSHIRE. FA

WEST RIDlNG YORKSHIRE. FA. a . Turner Thomas, .Abbey farm, Wath- Valentine John, Woodhouse, Stainton, Wade Mrs. A. Thurgoland ball, Sheffid upon-Dearne, Rotherham Rotherham Wade C. Booth stead, Warley, Halifax Turner Thoma_~~; .Alllwark, Rotherham Vardy Philip Geo. Park bead, Ecclesall Wade Edwin, 276 tlticket la. Bradford Turnel' Thos. Howgill; Sedbetgli R.8.0 Bierlow, Sheffield Wade Francis, Silsden mobr, Leeds TnrnerT.8onderlandst<.T~khl.Rothrhm Varley Abraham, Grassington, 8kipton Wade John, Bradshaw lane, Halifax TornerTho& Elslin, Svkehou8e, -8elbv Variey Benjamin, Gargrave, Leeds Wade Jn. High a~h, Pannal, Harrogat~ Turrter Wm. Farnley Tyos, H uddersfl.d V arley Geo. Terrr ple,Tem pie H urst,Selhy Wade J. Bull ho. Tburlstone, Sheffield Turner Wm. Grindleton, Clitheroe Varley James,Mixenden t~tones, Halifax Wade Joseph, 301 Rooley lane, Bradford Turner Wm. New hall, Rathmell,Settle Varley Joseph, Hoo hole,Mytholmroyd, Wade Mrs. Martba, Edge,Silsden, Leeds Turner Wm. Saville house., Hazlehead, Manchester Wade Robert, Kirkgate, Sil.sden, Leeds Sheffield I Varley Mrs. 1\fary, Great Heck, Selby Wade Robert, Silsden moor, Leeds Turner William, Shepley, Huddersfield Varley Rohert, Cononley, Leeds Wade Miss 8atrah A. Pannal, Harrogate Turner William,.Woodhouse, S!Jeffield VarleySl. G:reyston~s, Ovenden,Ralifax Wade Sykes, Balne, Selby Turner Wm. C. Stainton, Rotberharn Varley Thomas, West Marton, l:5kipton Wade T. High royd, Rang-e bank,Ifalifx Turner WilliamHenry,UpperBallbents, Varley Waiter, Melrham, Huddersfield Wade TltoruiUI Edwin, Wike, Leeds ?.Ieltham, Huddersfield Varley Wm. Barwick-in-Elmet, Leeds Wade William, Rufforth, York Turpla Mrs. Ann, Embsay, Sklpton Varley Wm. Hagg~, Colton, Tadcaster Waddington Henry, High Coates~ Turpin W. Twisletoningleton ,Carnforth Vaughton George, Oxspring, Sheffield Wilsden, Bingley Turr Gervas, Button, Doncaster VauseEdwd.Hardwick,Aston,Rotherhm Wadsworth Alex. -

Health Profile Overview for Garforth and Swillington Ward

Garforth and Swillington Ward Health profile overview for Garforth and Swillington ward Population: 21,325 Garforth and Swillington ward has a GP registered Comparison of ward Leeds age structures July 2018. population of 21,325 making it the fifth smallest ward Mid range Most deprived 5th Least deprived 5th in Leeds with the majority of the ward population living in the second least deprived fifth of Leeds. In 100-104 Males: 10,389 Females: 10,936 Leeds terms the ward is ranked sixth least by 90-94 deprivation score . 80-84 70-74 The age profile of this ward is very different to Leeds, 60-64 but with many more elderly and far adults and children. 50-54 This profile presents a high level summary of health 40-44 related data sets for the Garforth and Swillington 30-34 ward. 20-24 10-14 All wards are ranked to display variation across Leeds 0-4 and this one is outlined in red. 6% 3% 0% 3% 6% Leeds overall is shown as a horizontal black line, Deprived Deprivation in this ward Leeds** (or the most deprived fifth**) is an orange dashed Proportions of this population within each deprivation 'quintile' horizontal. The MSOAs that make up this ward are overlaid or fifth of Leeds* (Leeds therefore has equal proportions of 20%) as red circles and often range widely. July 2018. 63% Most of the data is provided for the new wards as redesigned in 2018, however 'obese smokers', and 'child 37% obesity' are for the previous wards and the best match is used in these cases. -

Properties for Customers of the Leeds Homes Register

Welcome to our weekly list of available properties for customers of the Leeds Homes Register. Bidding finishes Monday at 11.59pm. For further information on the properties listed below, how to bid and how they are let please check our website www.leedshomes.org.uk or telephone 0113 222 4413. Please have your application number and CBL references to hand. Alternatively, you can call into your local One Stop Centre or Community Hub for assistance. Date of Registration (DOR) : Homes advertised as date of registration (DOR) will be let to the bidder with the earliest date of registration and a local c onnection to the Ward area. Successful bidders will need to provide proof of local connection within 3 days of it being requested. Maps of Ward areas can be found at www.leeds.gov.uk/wardmaps Aug 11 2021 to Aug 16 2021 Ref Landlord Address Area Beds Type Sheltered Adapted Rent Description DOR Silkstone House, Fox Lane, Allerton Single or a couple 11029 Home Group Bywater, WF10 2FP Kippax and Methley 1 Flat No No 411.11 No BAILEYS HILL, SEACROFT, LEEDS, Single/couple 11041 The Guinness LS14 6PS Killingbeck and Seacroft 1 Flat No No 76.58 No CLYDE COURT, ARMLEY, LEEDS, LS12 Single/couple 11073 Leeds City Council 1XN Armley 1 Bedsit No No 63.80 No MOUNT PLEASANT, KIPPAX, LEEDS, Single 55+ 11063 Leeds City Council LS25 7AR Kippax and Methley 1 Bedsit No No 83.60 No SAXON GROVE, MOORTOWN, LEEDS, Single/couple 11059 Leeds City Council LS17 5DZ Alwoodley 1 Flat No No 68.60 No FAIRFIELD CLOSE, BRAMLEY, LEEDS, Single/couple 25+ 11047 Leeds City Council -

The Boundary Committee for England Periodic Electoral Review of Leeds

K ROAD BARWIC School School Def School STANKS R I School N G R O A D PARLINGTON CP C R O PARKLANDS S S G A T E S HAREWOOD WARD KILLINGBECK AND School PENDA'S FIELDS SEACROFT WARD MANSTON CROSS GATES AND WHINMOOR WARD D A O BARWICK IN ELMET AND R Def D R O SCHOLES CP F R E Def B A CROSS GATES ROAD U n S T d A T I O Barnbow Common N R School O A D Seacroft Hospital Def A 6 5 6 2 4 6 A f De R IN G R O A D H A Def L A T U O S N T H O R P E GRAVELEYTHORPE L A N E U f nd e D N EW HO LD NE LA IRK ITK Elmfield WH nd Business U Park Newhold Industrial Estate E Recreation AN AUSTHORPE Y L Ground WB RO BAR School f e School STURTON GRANGE CP D A 6 5 WHITKIRK LANE END AUSTHORPE WEST 6 PARISH WARD AUSTHORPE CP MOOR GARFORTH School EAST GARFORTH The Oval f AUSTHORPE EAST e D PARISH WARD SE School LB Y RO AD f e D Recreation Football Ground Ground Cricket Ground f e D Swillington Common COLTON School CHURCH GARFORTH School Cricket Ground Allotment Gardens LIDGETT f e D School GARFORTH TEMPLE NEWSAM WARD Schools Swillington Common U D A n College O d R m a s a N n w A e e r M n A O le s B t p r R U m o P e p L T S L E C R T H OR D P L E L E A WEST I N E GARFORTH F E L K C I M SE LB Y R O D AD e f A 63 Hollinthorpe Hollinthorpe 6 5 D 6 e A A 63 f A LE ED S School RO A D D i s m a n t le d R a il w a y K ip p a x B e c k Def SWILLINGTON CP Kippax Common Recreation Ground Ledston Newsam GARFORTH AND SWILLINGTON WARD Luck Green Swillington School School Kippax School Allotment Gardens School D A O R E G D I R Allotment Sports Ground Gardens Sports Grounds -

Oral Health Needs Assessment for Wakefield

Oral Health Needs Assessment Wakefield District Ian Walker Public Health Specialty Registrar March 2015 1 1.0 Executive summary Over the last thirty years there have been significant improvements in oral health in the UK, however many people still suffer the pain and discomfort of oral diseases which are largely preventable and remain a major public health problem. Decaying teeth constitutes the number one, most prevalent disease globally, with tooth decay (dental caries) and gum disease (periodontal disease) being the most common dental problems in the UK. There is a cumulative effect if unchecked in early stages of life, which leads to more pervasive decay in adulthood and higher chances of extensive tooth loss in later life. The distribution and severity of oral diseases varies between and within countries and regions and whilst sections of the British population enjoy very good levels of oral health, stark inequalities exist with some of the poorest and most disadvantaged sections of society facing significant oral health problems. This oral health needs assessment (OHNA) provides a detailed picture of the oral health needs of the Wakefield district and the commissioned dental services and oral health promotion services to meet those needs. It identifies gaps in provision and identifies key issues to be prioritised and addressed within future work on oral health in the district. Oral health of children 5 year olds in Wakefield are now 1½ times more likely to have some dental decay than 5 year olds across England. For an average group of 100 Wakefield children aged 5, there would be 41 with some dental decay, compared with 28 from an average group of 100 children from England. -

Health Profile Overview for Burmantofts and Richmond Hill Ward

Burmantofts and Richmond Hill Ward Health profile overview for Burmantofts and Richmond Hill ward Population: 30,290 Burmantofts and Richmond Hill ward has a GP Comparison of ward Leeds age structures July 2018. registered population of 30,290 making it the fifth Mid range Most deprived 5th Least deprived 5th largest ward in Leeds with the majority of the ward population living in the most deprived fifth of Leeds. 100-104 Males: 15,829 Females: 14,458 In Leeds terms the ward is ranked second by 90-94 deprivation score . 80-84 70-74 The age profile of this ward is similar to Leeds, but 60-64 with fewer elderly and many more children. 50-54 This profile presents a high level summary of health 40-44 related data sets for the Burmantofts and Richmond 30-34 Hill ward. 20-24 10-14 All wards are ranked to display variation across Leeds 0-4 and this one is outlined in red. 6% 3% 0% 3% 6% Leeds overall is shown as a horizontal black line, Deprived Deprivation in this ward Leeds** (or the most deprived fifth**) is an orange dashed Proportions of this population within each deprivation 'quintile' horizontal. The MSOAs that make up this ward are overlaid or fifth of Leeds* (Leeds therefore has equal proportions of 20%) as red circles and often range widely. July 2018. 81% Most of the data is provided for the new wards as redesigned in 2018, however 'obese smokers', and 'child obesity' are for the previous wards and the best match is 19% used in these cases. -

4F Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

4F bus time schedule & line map 4F Pudsey - Seacroft View In Website Mode The 4F bus line (Pudsey - Seacroft) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Pudsey <-> Leeds City Centre: 10:32 PM (2) Pudsey <-> Pudsey: 6:47 PM - 11:32 PM (3) Pudsey <-> Seacroft: 5:10 AM - 9:32 PM (4) Seacroft <-> Leeds City Centre: 11:28 PM (5) Seacroft <-> Pudsey: 5:22 AM - 10:28 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 4F bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 4F bus arriving. Direction: Pudsey <-> Leeds City Centre 4F bus Time Schedule 46 stops Pudsey <-> Leeds City Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 10:32 PM Pudsey Bus Stn F, Pudsey Cranshaw Hill, Leeds Tuesday 10:32 PM Pudsey Park, Pudsey Wednesday 10:32 PM Northrop's Yard, Leeds Thursday 10:32 PM Pudsey Chapeltown, Pudsey Friday 10:32 PM 19 Chapeltown, Leeds Saturday Not Operational Greenside, Pudsey Chapeltown, Leeds School Street, Pudsey Greenside, Leeds 4F bus Info Direction: Pudsey <-> Leeds City Centre Greentop, Pudsey Stops: 46 Trip Duration: 50 min Carlisle Road, Troydale Line Summary: Pudsey Bus Stn F, Pudsey, Pudsey Park, Pudsey, Pudsey Chapeltown, Pudsey, Hillthorpe Road, Pudsey Greenside, Pudsey, School Street, Pudsey, Greentop, Moravia Bank, Leeds Pudsey, Carlisle Road, Troydale, Hillthorpe Road, Pudsey, Southroyd Rise, Pudsey, Oakdene Close, Southroyd Rise, Pudsey Pudsey, Roker Lane, Pudsey, Southroyd Prim Sch, Southroyd Villas, Leeds Pudsey, Radcliffe Lane, Pudsey, Spinners Chase, Pudsey, Pudsey Town Hall, Pudsey, -

2. Scout Rock 3. Churn Milk Joan

BREARLEY LANE From the top of Scout Rock, view across to Midgeley Chapel. Photo: Jade Smith \ Map © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Calderdale MBC (100023069) (2006) View across to Banksfield and Wadsworth Bank Photo: Jade Smith By Low Bank Farm, follow the footpath straight uphill. It Into Brearley Lane by crossing railway bridge, and 2. Scout Rock continues upwards, roughly cobbled. Look ahead for views continuing down track. Cross over River Calder at Brearley over Calder Valley towards Foster Clough and Churn Milk Bridge, noticing remains of weir below. Brearley, a small Moderate walk of about 2½ miles (4 km), taking 1½ hours. Joan, to your left, Heptonstall Church and Old Town mill rural industrial hamlet, had at least three woollen mills, standing on the horizon. and is still used for business premises. Just before the Rising steeply at the start, it soon gives wonderful views second bridge, turn left along the canal; the old wall on Above Scout Rock: when the track bends right, turn left across the Calder Valley to Heptonstall and Old Town. Ted the opposite canal bank are the remains of an old toffee up small steps. Follow grassy path along lie of hill, glancing Hughes, from his childhood home in Aspinall Street in factory, still working within living memory. Mytholmroyd, looked straight across to the grim cliff-face left down onto Mytholmroyd, with Aspinall Street, Ted of Scout Rock: it provided ‘both the curtain and back-drop Hughes’ birthplace, just visible. Skirt along the hillside: The Canal path returns you to Mytholmroyd. As you to existence’. -

Site Allocations Plan Leeds Local Plan

Site Allocations Plan Leeds Local Plan Council’s response to Inspectors Actions arising from hearing sessions held 9th July to 3rd August October 2018 Contents Page Actions Week Commencing 9 July 2018 1 Actions Week Commencing 16 July 2018 3 Actions Week Commencing 30 July 2018 6 Main Modifications 8 List of Appendices Appendix 1 – Sustainability Appraisal Addendum – SA of Identified 11 Sites (relating to Question 16 Week Commencing 16 July 2018) Appendix 2 – Update of EX2c Update of Planning Status of Identified 84 Sites (relating to Question 18 Week Commencing 16 July 2018) Appendix 3 – Plan of East Leeds Orbital Route in relation to HG2-119 125 (relating to Question 20 Week Commencing 16 July 2018) Appendix 4 – Statement of Common Ground East Leeds Extension 127 (relating to Question 21 Week Commencing 16 July 2018) Appendix 5 – Inclusion of Additional Land within the Green Belt 132 (relating to Question 27 Week Commencing 16 July 2018) Appendix 6 – Nether Yeadon Conservation Area Appraisal (relating to 146 Week Commencing 30 July 2018 Aireborough Question 3) Appendix 7 – HS2 Proposals in relation to site HG2-179 (relating to 173 Week commencing 30 July 2018 Outer South Question 1) Appendix 8 – Scrutiny Board report and minutes for 21/12/16 (relating 175 to Week commencing 30 July 2018 Outer North East Question 1) Week Commencing 9 July 2018 1. Council to consider wording for Main modification to Policy BL1 to clarify that any SAP review will be completed by March 2023. As a consequence of the Inspectors Post-Hearing Procedural Note (EX72a) this is no longer considered to be a necessary action. -

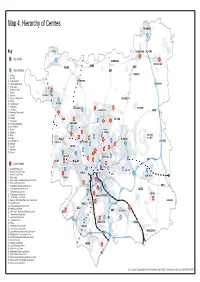

Map 4. Hierarchy of Centres WETHERBY

Map 4. Hierarchy of Centres WETHERBY 27 Key OTLEY COLLINGHAM A1 (M) 9 City Centre 4 22 HAREWOOD BOSTON SPA A659 A660 A58 Town Centres A61 1 Armley BARDSEY 2 Bramley 3 Chapel Allerton BRAMHOPE 4 Colton (Selby Road) BRAMHAM 5 Cross Gates 6 Dewsbury Road 12 7 Farsley 9 8 Garforth GUISELEY 9 Guiseley, Otley Road 28 SCARCROFT 10 Halton 11 Harehills Lane YEADON 12 Headingley COOKRIDGE 1 29 THORNER 13 Holt Park 13 ALWOODLEY A64 14 Horsforth, Town Street 27 15 Hunslet 16 Kirkstall A65A6A65 18 A6120A6A61661201212020 17 Meanwood 19 26 3311 18 Middleton Ring Road HORSFORTHHORSFOS RTHRTTHTH 19 Moor Allerton 141 20 Morley CHAPELCHAC PEL 21 Oakwood 6 AALLALLERTONERTRTR ONN 17 BARWICKBARARW 22 Otley 3 23 Pudsey 14 3333 1177 IN ELMETELM A657A6577 25 SEACROFTSEASE CRROR FTT 24 Richmond Hill 221 A1 (M) CALVERLEYCACALC VERRLEYY HEADINGLEYHHEAHEADIND GLLEY 25 Rothwell 1212 16 26 RODLEYRODR LEYY 26 Seacroft 133 8 27 Wetherby 1166 1199 28 Yeadon 7 2 28 FARSLEYFARARSLSLES Y HAREHILLSHAREHILLS 11 5 2121 5 M1 A647A6477 300 BRAMLEYBRABBRRARAMMLEY Local Centres 22 24 1 Alwoodley King Lane 23 1 CITYY 10 2 Beeston Hill Local Centre HALTONHALTON 8 7 ARMLEY CENTRECCENENTRTRETR 4 3 Beeston Local Centre GARFORTH 4 Boston Spa PUDSEY 5 Burley Lodge (Woodsley Road) Local Centre 15 6 Butcher Hill Local Centre 23 7 Chapeltown (Pudsey) Local Centre A63 2 15 8 Chapeltown Road Local Centre 6 A642 9 Collingham Local Centre 10 Drighlington Local Centre 3 KIPPAX BEESTON M621 11 East Ardsley Local Centre 20 12 Guiseley Oxford Road/Town Gate Town Centre 32 LEDSHAM 13 Harehills Corner