Arxiv:2010.05676V1 [Math.RA]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Cohomology and Matlis Duality – Table of Contents 0Introduction

Local Cohomology and Matlis duality { Table of contents 0 Introduction . 2 1 Motivation and General Results . 6 1.1 Motivation . 6 1.2 Conjecture (*) on the structure of Ass (D( h (R))) . 10 R H(x1;:::;xh)R h 1.3 Regular sequences on D(HI (R)) are well-behaved in some sense . 13 1.4 Comparison of two Matlis Duals . 15 2 Associated primes { a constructive approach . 19 3 Associated primes { the characteristic-free approach . 26 3.1 Characteristic-free versions of some results . 26 dim(R)¡1 3.2 On the set AssR(D(HI (R))) . 28 4 The regular case and how to reduce to it . 35 4.1 Reductions to the regular case . 35 4.2 Results in the general case, i. e. h is arbitrary . 36 n¡2 4.3 The case h = dim(R) ¡ 2, i. e. the set AssR(D( (k[[X1;:::;Xn]]))) . 38 H(X1;:::;Xn¡2)R 5 On the meaning of a small arithmetic rank of a given ideal . 43 5.1 An Example . 43 5.2 Criteria for ara(I) · 1 and ara(I) · 2 ......................... 44 5.3 Di®erences between the local and the graded case . 48 6 Applications . 50 6.1 Hartshorne-Lichtenbaum vanishing . 50 6.2 Generalization of an example of Hartshorne . 52 6.3 A necessary condition for set-theoretic complete intersections . 54 6.4 A generalization of local duality . 55 7 Further Topics . 57 7.1 Local Cohomology of formal schemes . 57 i 7.2 D(HI (R)) has a natural D-module structure . -

Local Cohomology and Base Change

LOCAL COHOMOLOGY AND BASE CHANGE KAREN E. SMITH f Abstract. Let X −→ S be a morphism of Noetherian schemes, with S reduced. For any closed subscheme Z of X finite over S, let j denote the open immersion X \ Z ֒→ X. Then for any coherent sheaf F on X \ Z and any index r ≥ 1, the r sheaf f∗(R j∗F) is generically free on S and commutes with base change. We prove this by proving a related statement about local cohomology: Let R be Noetherian algebra over a Noetherian domain A, and let I ⊂ R be an ideal such that R/I is finitely generated as an A-module. Let M be a finitely generated R-module. Then r there exists a non-zero g ∈ A such that the local cohomology modules HI (M)⊗A Ag are free over Ag and for any ring map A → L factoring through Ag, we have r ∼ r HI (M) ⊗A L = HI⊗AL(M ⊗A L) for all r. 1. Introduction In his work on maps between local Picard groups, Koll´ar was led to investigate the behavior of certain cohomological functors under base change [Kol]. The following theorem directly answers a question he had posed: f Theorem 1.1. Let X → S be a morphism of Noetherian schemes, with S reduced. Suppose that Z ⊂ X is closed subscheme finite over S, and let j denote the open embedding of its complement U. Then for any coherent sheaf F on U, the sheaves r f∗(R j∗F) are generically free and commute with base change for all r ≥ 1. -

Lectures on Local Cohomology

Contemporary Mathematics Lectures on Local Cohomology Craig Huneke and Appendix 1 by Amelia Taylor Abstract. This article is based on five lectures the author gave during the summer school, In- teractions between Homotopy Theory and Algebra, from July 26–August 6, 2004, held at the University of Chicago, organized by Lucho Avramov, Dan Christensen, Bill Dwyer, Mike Mandell, and Brooke Shipley. These notes introduce basic concepts concerning local cohomology, and use them to build a proof of a theorem Grothendieck concerning the connectedness of the spectrum of certain rings. Several applications are given, including a theorem of Fulton and Hansen concern- ing the connectedness of intersections of algebraic varieties. In an appendix written by Amelia Taylor, an another application is given to prove a theorem of Kalkbrenner and Sturmfels about the reduced initial ideals of prime ideals. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Local Cohomology 3 3. Injective Modules over Noetherian Rings and Matlis Duality 10 4. Cohen-Macaulay and Gorenstein rings 16 d 5. Vanishing Theorems and the Structure of Hm(R) 22 6. Vanishing Theorems II 26 7. Appendix 1: Using local cohomology to prove a result of Kalkbrenner and Sturmfels 32 8. Appendix 2: Bass numbers and Gorenstein Rings 37 References 41 1. Introduction Local cohomology was introduced by Grothendieck in the early 1960s, in part to answer a conjecture of Pierre Samuel about when certain types of commutative rings are unique factorization 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 13C11, 13D45, 13H10. Key words and phrases. local cohomology, Gorenstein ring, initial ideal. The first author was supported in part by a grant from the National Science Foundation, DMS-0244405. -

Advanced Commutative Algebra Lecture Notes

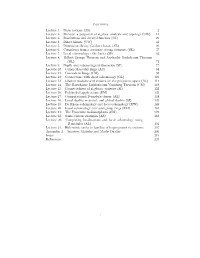

Advanced Commutative Algebra Lecture Notes Lecturer: Paul Smith; written and edited by Josh Swanson September 30, 2015 Abstract The following notes were taking during a course on Advanced Commutative Algebra at the University of Washington in Fall 2014. Please send any corrections to [email protected]. Thanks! Contents September 24th, 2014: Tensor Product Definition, Universal Property................2 September 26th, 2014: Tensor-Hom Adjunction, Right Exactness of Tensor Products, Flatness..4 September 29th, 2014: Tensors and Quotients, Support of a Module.................6 October 1st, 2014: Prime Avoidance Lemma, Associated Primes...................9 October 3rd, 2014: Associated Primes Continued, Minimal Primes, Zero-Divisors, Regular Elements 10 October 6th, 2014: Duality Theories, Injective Envelopes, and Indecomposable Injectives..... 12 October 8th, 2014: Local Cohomology Defined............................. 14 October 10th, 2014: Examples of Injectives and Injective Hulls.................... 16 October 13th, 2014: Local Cohomology and Depth through Ext; Matlis Duality........... 18 October 15th, 2014: Matlis Duality Continued............................. 20 October 17th, 2014: Local Cohomology and Injective Hulls Continued................ 22 October 20th, 2014: Auslander-Buchsbaum Formula; Nakayama's Lemma.............. 24 October 22nd, 2014: Dimension Shifting, Rees' Theorem, Depth and Regular Sequences...... 26 October 27th, 2014: Krull Dimension of Modules............................ 28 October 29th, 2014: Local Cohomology over -

(AS) 2 Lecture 2. Sheaves: a Potpourri of Algebra, Analysis and Topology (UW) 11 Lecture 3

Contents Lecture 1. Basic notions (AS) 2 Lecture 2. Sheaves: a potpourri of algebra, analysis and topology (UW) 11 Lecture 3. Resolutions and derived functors (GL) 25 Lecture 4. Direct Limits (UW) 32 Lecture 5. Dimension theory, Gr¨obner bases (AL) 49 Lecture6. Complexesfromasequenceofringelements(GL) 57 Lecture7. Localcohomology-thebasics(SI) 63 Lecture 8. Hilbert Syzygy Theorem and Auslander-Buchsbaum Theorem (GL) 71 Lecture 9. Depth and cohomological dimension (SI) 77 Lecture 10. Cohen-Macaulay rings (AS) 84 Lecture 11. Gorenstein Rings (CM) 93 Lecture12. Connectionswithsheafcohomology(GL) 103 Lecture 13. Graded modules and sheaves on the projective space(AL) 114 Lecture 14. The Hartshorne-Lichtenbaum Vanishing Theorem (CM) 119 Lecture15. Connectednessofalgebraicvarieties(SI) 122 Lecture 16. Polyhedral applications (EM) 125 Lecture 17. Computational D-module theory (AL) 134 Lecture 18. Local duality revisited, and global duality (SI) 139 Lecture 19. De Rhamcohomologyand localcohomology(UW) 148 Lecture20. Localcohomologyoversemigrouprings(EM) 164 Lecture 21. The Frobenius endomorphism (CM) 175 Lecture 22. Some curious examples (AS) 183 Lecture 23. Computing localizations and local cohomology using D-modules (AL) 191 Lecture 24. Holonomic ranks in families of hypergeometric systems 197 Appendix A. Injective Modules and Matlis Duality 205 Index 215 References 221 1 2 Lecture 1. Basic notions (AS) Definition 1.1. Let R = K[x1,...,xn] be a polynomial ring in n variables over a field K, and consider polynomials f ,...,f R. Their zero set 1 m ∈ V = (α ,...,α ) Kn f (α ,...,α )=0,...,f (α ,...,α )=0 { 1 n ∈ | 1 1 n m 1 n } is an algebraic set in Kn. These are our basic objects of study, and include many familiar examples such as those listed below. -

Duality in Algebra and Topology

DUALITY IN ALGEBRA AND TOPOLOGY W. G. DWYER, J. P. C. GREENLEES, AND S. IYENGAR Dedicated to Clarence W. Wilkerson, on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Spectra, S-algebras, and commutative S-algebras 7 3. Some basic constructions with modules 13 4. Smallness 20 5. Examples of smallness 27 6. Matlis lifts 29 7. Examples of Matlis lifting 33 8. Gorenstein S-algebras 36 9. A local cohomology theorem 41 10. Gorenstein examples 44 References 47 1. Introduction In this paper we take some classical ideas from commutative algebra, mostly ideas involving duality, and apply them in algebraic topology. To accomplish this we interpret properties of ordinary commutative rings in such a way that they can be extended to the more general rings that come up in homotopy theory. Amongst the rings we work with are the di®erential graded ring of cochains on a space X, the dif- ferential graded ring of chains on the loop space X, and various ring spectra, e.g., the Spanier-Whitehead duals of ¯nite spectra or chro- matic localizations of the sphere spectrum. Maybe the most important contribution of this paper is the concep- tual framework, which allows us to view all of the following dualities ² Poincar¶e duality for manifolds ² Gorenstein duality for commutative rings ² Benson-Carlson duality for cohomology rings of ¯nite groups Date: October 3, 2005. 1 2 W. G. DWYER, J. P. C. GREENLEES, AND S. IYENGAR ² Poincar¶e duality for groups ² Gross-Hopkins duality in chromatic stable homotopy theory as examples of a single phenomenon. -

![Arxiv:1710.10840V1 [Math.NT] 30 Oct 2017 Ewe Oteinadartinian and Noetherian Between D R O Nt Eiu Ed Osdrfrhroean Furthermore Consider field](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8357/arxiv-1710-10840v1-math-nt-30-oct-2017-ewe-oteinadartinian-and-noetherian-between-d-r-o-nt-eiu-ed-osdrfrhroean-furthermore-consider-eld-2528357.webp)

Arxiv:1710.10840V1 [Math.NT] 30 Oct 2017 Ewe Oteinadartinian and Noetherian Between D R O Nt Eiu Ed Osdrfrhroean Furthermore Consider field

ON SPECTRAL SEQUENCES FOR IWASAWA ADJOINTS À LA JANNSEN FOR FAMILIES OLIVER THOMAS AND OTMAR VENJAKOB Abstract. In [5] several spectral sequences for (global and local) Iwasawa modules over (not necessarily commutative) Iwasawa algebras (mainly of p- adic Lie groups) over Zp are established, which are very useful for determining certain properties of such modules in arithmetic applications. Slight generaliza- tions of said results can be found in [10] (for abelian groups and more general coefficient rings), [13] (for products of not necessarily abelian groups, but with Zp-coefficients), and [8]. Unfortunately, some of Jannsen’s spectral sequences for families of representations as coefficients for (local) Iwasawa cohomology are still missing. We explain and follow the philosophy that all these spectral sequences are consequences or analogues of local cohomology and duality à la Grothendieck (and Tate for duality groups). Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Conventions 2 3. A few facts on R-modules 3 3.1. Noncommutative rings 3 3.2. The Koszul Complex 6 3.3. Local Cohomology 7 4. (Avoiding) Matlis Duality 9 5. Tate Duality and Local Cohomology 11 6. Iwasawa Adjoints 15 7. Local Duality for Iwasawa Algebras 19 8. Torsion in Iwasawa Cohomology 20 8.1. TorsioninLocalIwasawaCohomology 20 8.2. Torsion in Global Iwasawa Cohomology 21 References 21 arXiv:1710.10840v1 [math.NT] 30 Oct 2017 1. Introduction Let be a complete discrete valuation ring with uniformising element π and finite residueO field. Consider furthermore an -algebra R, which is a complete Noetherian local ring with maximal ideal m,O of dimension d and finite residue field. -

Local Cohomology

LOCAL COHOMOLOGY by Mel Hochster These are lecture notes based on seminars and courses given by the author at the Univer- sity of Michigan over a period of years. This particular version is intended for Mathematics 615, Winter 2011. The objective is to give a treatment of local cohomology that is quite elementary, assuming, for the most part, only a modest knowledge of commutative alge- bra. There are some sections where further prerequisites, usually from algebraic geometry, are assumed, but these may be omitted by the reader who does not have the necessary background. This version contains the first twenty sections, and is tentative. There will be extensive revisions and additions. The final version will also have Appendices dealing with some prerequisites. ||||||||| Throughout, all given rings are assumed to be commutative, associative, with identity, and all modules are assumed to be unital. By a local ring (R; m; K) we mean a Noetherian ring R with a unique maximal ideal m and residue field K = R=m. Topics to be covered include the study of injective modules over Noetherian rings, Matlis duality (over a complete local ring, the category of modules with ACC is anti- equivalent to the category of modules with DCC), the notion of depth, Cohen-Macaulay and Gorenstein rings, canonical modules and local duality, the Hartshorne-Lichtenbaum vanishing theorem, and the applications of D-modules (in equal characteristic 0) and F- modules (in characteristic p > 0) to study local cohomology of regular rings. The tie-in with injective modules arises, in part, because the local cohomology of a regular local rings with support in the maximal ideal is the same as the injective huk of the residue class field. -

Grothendieck-Neeman Duality and the Wirthm¨Uller

GROTHENDIECK-NEEMAN DUALITY AND THE WIRTHMULLER¨ ISOMORPHISM PAUL BALMER, IVO DELL'AMBROGIO, AND BEREN SANDERS Abstract. We clarify the relationship between Grothendieck duality `ala Nee- man and the Wirthm¨ullerisomorphism `ala Fausk-Hu-May. We exhibit an interesting pattern of symmetry in the existence of adjoint functors between compactly generated tensor-triangulated categories, which leads to a surprising trichotomy: There exist either exactly three adjoints, exactly five, or infinitely many. We highlight the importance of so-called relative dualizing objects and explain how they give rise to dualities on canonical subcategories. This yields a duality theory rich enough to capture the main features of Grothendieck duality in algebraic geometry, of generalized Pontryagin-Matlis duality `ala Dwyer-Greenless-Iyengar in the theory of ring spectra, and of Brown-Comenetz duality `ala Neeman in stable homotopy theory. Contents 1. Introduction and statement of results1 2. Brown representability and the three basic functors7 3. Grothendieck-Neeman duality and ur-Wirthm¨uller 11 4. The Wirthm¨ullerisomorphism 17 5. Grothendieck duality on subcategories 21 6. Categories over a base and relative compactness 29 7. Examples beyond Grothendieck duality 31 References 34 1. Introduction and statement of results A tale of adjoint functors. Consider a tensor-exact functor f ∗ : D ! C between tensor-triangulated categories. As the notation f ∗ suggests, one typically obtains such functors by pulling-back representations, sheaves, spectra, etc., along some suitable \underlying" map f : X ! Y of groups, spaces, schemes, etc. (The actual underlying map f is not relevant for our discussion. Moreover, our choice of nota- tion f ∗ is geometric in spirit, i.e. -

Modules with Injective Cohomology, and Local Duality for a Finite Group

New York Journal of Mathematics New York J. Math. 7 (2001) 201–215. Modules with Injective Cohomology, and Local Duality for a Finite Group David Benson Abstract. Let G be a finite group and k a field of characteristic p dividing |G|. Then Greenlees has developed a spectral sequence whose E2 term is the local cohomology of H∗(G, k) with respect to the maximal ideal, and which converges to H∗(G, k). Greenlees and Lyubeznik have used Grothendieck’s dual localization to provide a localized form of this spectral sequence with respect to a homogeneous prime ideal p in H∗(G, k), and converging to the ∗ injective hull Ip of H (G, k)/p. The purpose of this paper is give a representation theoretic interpreta- tion of these local cohomology spectral sequences. We construct a double complex based on Rickard’s idempotent kG-modules, and agreeing with the Greenlees spectral sequence from the E2 page onwards. We do the same for the Greenlees-Lyubeznik spectral sequence, except that we can only prove that the E2 pages are isomorphic, not that the spectral sequences are. Ours converges to the Tate cohomology of the certain modules κp introduced in a paper of Benson, Carlson and Rickard. This leads us to conjecture that ∗ ∼ Hˆ (G, κp ) = Ip , after a suitable shift in degree. We draw some consequences of this conjecture, including the statement that κp is a pure injective module. We are able to prove the conjecture in some cases, including the case where ∗ H (G, k)p is Cohen–Macaulay. Contents 1. -

Triangulated Categories and Applications

Université de Lille 1 – Sciences et Technologies Synthèse des travaux présentés pour obtenir le diplôme Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches Spécialité Mathématiques Triangulated categories and applications Présentée par Ivo DELL’AMBROGIO le 29 septembre 2016 Rapporteurs Serge BOUC Henning KRAUSE Amnon NEEMAN Jury Christian AUSONI Serge BOUC Benoit FRESSE Henning KRAUSE Amnon NEEMAN Jean-Louis TU Acknowledgements Most of what I know I have learned from colleagues over the years, in conver- sation, by listening to their talks and by reading their work. I’ve had the good fortune and the pleasure to collaborate with several of them, and I sincerely wish to thank them all for their generosity and their friendship. As far as I’m concerned, mathematics is much better as a team sport. I am grateful to my Lille colleagues for having welcomed me so warmly within their ranks these last four years. Extra thanks to Benoit Fresse for offering to be my HDR ‘garant’, and for patiently guiding me through the administrative steps. I am very grateful to Serge Bouc, Henning Krause and Amnon Neeman for accepting to write the reports, and to Christian Ausoni and Jean-Louis Tu for accepting to be part of the jury. Last but not least, much love to Ola for her continuous support. 2 Introduction4 1 Triangulated categories and homological algebra 10 1.1 Preliminaries on triangulated categories.............. 10 1.2 Universal coefficient theorems.................... 13 1.3 Applications: Brown-Adams representability............ 18 1.4 UCT’s for the KK-theory of C*-algebras.............. 21 1.5 Equivariant KK-theory and Mackey functors.......... -

Local Cohomology and Base Change

Journal of Algebra 496 (2018) 11–23 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Algebra www.elsevier.com/locate/jalgebra ✩ Local cohomology and base change Karen E. Smith a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t f Article history: Let X −→ S be a morphism of Noetherian schemes, with S Received 7 February 2017 reduced. For any closed subscheme Z of X finite over S, Available online 4 November 2017 let j denote the open immersion X \ Z→ X. Then for Communicated by Luchezar L. F \ ≥ Avramov any coherent sheaf on X Z and any index r 1, the sheaf f∗(Rrj∗F)is generically free on S and commutes with Keywords: base change. We prove this by proving a related statement Local cohomology about local cohomology: Let R be Noetherian algebra over a Generic freeness Noetherian domain A, and let I ⊂ R be an ideal such that Matlis duality R/I is finitely generated as an A-module. Let M be a finitely Local Picard group generated R-module. Then there exists a non-zero g ∈ A such Base change r ⊗ that the local cohomology modules HI (M) A Ag are free over Ag and for any ring map A → L factoring through Ag, we have Hr(M) ⊗ L ∼ Hr (M ⊗ L)forall r. I A = I⊗AL A © 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction In his work on maps between local Picard groups, Kollár was led to investigate the behavior of certain cohomological functors under base change [12].