Branston Brewery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free Events Inside

8th - 22nd July 2017 Back and better than ever! Two weeks full of walking and family fun for all ages. Join us and step out in to the beautiful Lincolnshire countryside. From themed walks to exploring our Stepping Out network, you’re bound to find something for you. Make sure to look out for those longer walks too. See inside for details. FREE EVENTS INSIDE Find us on Social Media KEY Get your Easy walk boots on… Moderate walk Energetic walk North Kesteven is privileged to have a vast and beautiful countryside Distance and has picturesque villages and exquisite medieval churches, a living Start point landscape steeped in history and Walk leader rich in wildlife. The North Kesteven Walking Festival is a celebration of P Parking the countless walking opportunities Cost of walk available within the District and we want you to celebrate with us too! Wheelchair / Pushchair accessible We have lots on offer; take a look at Cattle present our programme, you’ll be sure to Stiles find a walk for you. Heritage Bring packed lunch All walks are bookable and can be done so by contacting the events Refreshments available after walk team on 01522 694353 or email Toilet facilities [email protected] Dogs welcome PROGRAMME OF WALKS 1. Spires & Steeples Arts & Heritage Trail 3. Out Of The Danger Zone Part 1 Saturday 8th July, 10am for 10:30am start Saturday 8th July, 9am A hike from Beckingham around the ‘Danger Discover the rich history and heritage of Zone’, there should be plenty of wildlife to North Kesteven along the Spires & Steeples spot and possibly gunfire if the troops are Arts & Heritage Trail. -

Lincolnshire. Lincoln

DIRECTORY .J LINCOLNSHIRE. LINCOLN. 3~7 Mason Col. Ed.ward Snow D.L. 20 Minster yard, L!nooln Stovin George, Boothby, Lincoln Morton Wm. Henry esq. Washingborough manor, Lincoln Usher A. H. Wickenby Pea~s John esq. Mere~ Lincoln Warrener Col. John Matthew, Long Leys, Yarborough N_ev1le Edward Horaho esq. Skellingthorpe, Lincoln I road, Lincoln Sibt:horp )!ontague Richard Waldo esq. Oanwick hall, Wright Philip Chetwood J.P. Brattleby hall, Linculn Lmcoln Wright G. Gate Burton S~uttleworth_Alfred esq. D.L. Eastgate house, Lincoln The Mayor, Sheriff, Aldermen & Town Clerk of Lincoln Sibthorp C~nmgsby Charles esq. M.A., D.L. Sudbrooke 1 Clerk, William Barr Danby, 2 Bank street :S:olme, Lmcoln Surveyor, James Thropp M.I.C.E. 29 Broadgate, Lincoln Sm1th Eust~e Abcl esq. ~ong hills, Branston, Lincoln Bailiff & Collector, John Lnmley Bayner, 13 Bank street Tempest MaJor Arthur Cecil, Coleby hall, Lincoln Tempest Roger Stephen esq. Coleby hall, Lincoln PUBLIC ESTABLISHMENTS. Wray Cecil Henry esq. Swinderby, Linooln Aflboretum, Monks road, Gentle Smith, manager The Chairmen, for the time being, of the Bracebridge Butter Market, High street Urban & Branston Rural District Councils are ex-officio Cattle Markets, Monks road, James Hill, collector of tolls magistrates Church House & Institute, Christ's Hospital terrace, Steep Clerk to the Magistrates, Reginald Arthur Stephen, hill, Rt. Rev. the Lord Bishop of Lincoln, president; Sslterga>te, Lincoln R. C. Hallowes esq. treasurer; Rev. Canon E. T. Leeke Petty Sessions are held at the Justice's room, Lincoln &i R. ~-. MacBrair esq. hun. secs.; Charles W. Martin, orgamzmg sec Castle, the Ist & 3rd friday in every month at I 1.30 City Fire Brigade Engine House, Free School lane, John a.m. -

New Electoral Arrangements for North Kesteven District Council Final Recommendations January 2021

New electoral arrangements for North Kesteven District Council Final Recommendations January 2021 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licensing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2021 A note on our mapping: The maps shown in this report are for illustrative purposes only. Whilst best efforts have been made by our staff to ensure that the maps included in this report are representative of the boundaries described by the text, there may be slight variations between these maps and the large PDF map that accompanies this report, or the digital mapping supplied on our consultation portal. This is due to the way in which the final mapped products are produced. The reader should therefore refer to either the large PDF supplied with this report or the digital mapping for the true likeness of the boundaries intended. The boundaries as shown on either the large PDF map or the digital mapping should always appear identical. Contents Introduction 1 Who we are and what we do 1 What is an electoral review? 1 Why North Kesteven? 2 Our proposals for North Kesteven 2 How will the recommendations affect you? 2 Review -

Situations of Polling Stations

SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS UK Parliamentary Election: Sleaford and North Hykeham constituency Date of Election: Thursday 12 December 2019 Hours of Poll: 7:00 am to 10:00 pm Notice is hereby given that: The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Ranges of electoral Ranges of electoral Station register numbers of Station register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled to vote Number persons entitled to vote thereat thereat Cranwell, The Brunei Community Ashby de la Launde Village Hall, Church 1 AA-1 to AA-604/1 Centre/Hive, RAFC Cranwell, Cranwell, 2 AB001-1 to AB001-842 Avenue, Ashby de la Launde Sleaford Cranwell Village Hall, Old School Lane, Digby War Memorial Hall, North Street, AC-1 to AC-488 3 AB002-1 to AB002-1064 4 Cranwell Village, Sleaford Digby, Lincoln AE-3 to AE-124/1 Dorrington, Wesleyan Reform Chapel Scopwick and Kirkby Green Village Hall, School Room, 125 Main Street, Dorrington, 5 AD-1 to AD-301 6 AF-2 to AF-548 Brookside, Scopwick, Lincoln Lincoln Aubourn The Enterprise Centre, Bridge Bassingham Hammond Hall, Bassingham BB-1 to BB-1271 7 BA-1 to BA-272 8 Road, Aubourn, Lincoln Playing Fields, Lincoln Road, Bassingham BK-1 to BK-82 Beckingham Village Hall, Chapel Street, Brant Broughton Village Hall, West Street, 9 BC-1 to BC-302/1 10 BD-1 to BD-631 Beckingham, Lincoln Brant Broughton, Lincoln Carlton Le Moorland Village Hall, Church Norton Disney Village Hall, Main Street, BF-2 to BF-203 11 BE-1 to BE-469/3 -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Publication of the Hykeham Neighbourhood Plan

Publication of the Hykeham Neighbourhood Plan In accordance with the Central Lincolnshire Statement of Community Involvement, the following activities were undertaken in order to publicise the North Hykeham Town Council and South Hykeham Parish Council Neighbourhood Plan: 1. The consultation was published on the North Kesteven District Council website, and included: The plan and accompanying documents, Details of where and when the plan can be viewed (paper copies), Details of how people can comment (electronic and paper), Details of when comments must be received by, A statement that representations may include a request to be notified of future stages of the plan, and The response form. 2. Hard copies of the plan, supporting documents and response form were also made available at the following locations: The District Council Offices, North Hykeham Town Council Offices, North Hykeham Library and South Hykeham Village Hall. 3. Notify specific bodies / individuals: A number of bodies were consulted as detailed in the table overleaf. 4. Other publication/promotion: A press release was sent to local media stating where and when the plan could be reviewed, and how to provide formal responses. All feedback received was posted onto the District Council Website. 1 HYKEHAM NEIGHBOURHOOD DRAFT PLAN CONSULTATION LIST Organisation Contact Details Date Method Comments North Hykeham Email / Documents sent / Details posted for village Town Council hall notice boards and South Hykeham Parish Made available via North Hykeham Town Council Council website: Residents http://www.northhykehamtowncouncil.gov.uk/Ou r_Draft_Plan.aspx and South Hykeham Parish Council website: http://parishes.lincolnshire.gov.uk/SouthHykeham /section.asp?catId=35545 Documents available via the NKDC website, https://www.n-kesteven.gov.uk/residents/living- in-your-area/localism/neighbourhood-plans/north- and-south-hykeham-neighbourhood-plan/ Hard copies of these documents along with the 1. -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for North Kesteven in Lincolnshire

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for North Kesteven in Lincolnshire Further electoral review December 2005 1 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Executive summary 7 1 Introduction 15 2 Current electoral arrangements 19 3 Draft recommendations 23 4 Responses to consultation 25 5 Analysis and final recommendations 29 Electorate figures 29 Council size 31 Electoral equality 33 General analysis 34 Warding arrangements 35 a Bassingham, Brant Broughton, Cliff Villages, Eagle & North 35 Scarle and Skellingthorpe wards b The five wards of North Hykeham parish 44 c Bracebridge Heath & Waddington East, Branston & Mere, 48 Heighington & Washingborough and Waddington West wards d Ashby de la Launde, Billinghay, Martin and Metheringham wards 51 e The six wards of Sleaford parish 53 f Cranwell & Byard’s Leap, Heckington Rural, Kyme, Leasingham 58 & Roxholm, Osbournby and Ruskington wards Conclusions 65 6 What happens next? 71 7 Mapping 73 Appendices A Glossary and abbreviations 75 B Code of practice on written consultation 79 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. -

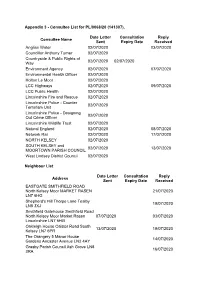

Appendix 3 - Consultee List for PL/0068/20 (141307)

Appendix 3 - Consultee List for PL/0068/20 (141307). Date Letter Consultation Reply Consultee Name Sent Expiry Date Received Anglian Water 02/07/2020 03/07/2020 Councillor Anthony Turner 02/07/2020 Countryside & Public Rights of 02/07/2020 02/07/2020 Way Environment Agency 02/07/2020 07/07/2020 Environmental Health Officer 02/07/2020 Holton Le Moor 02/07/2020 LCC Highways 02/07/2020 09/07/2020 LCC Public Health 02/07/2020 Lincolnshire Fire and Rescue 02/07/2020 Lincolnshire Police - Counter 02/07/2020 Terrorism Unit Lincolnshire Police - Designing 02/07/2020 Out Crime Officer Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust 02/07/2020 Natural England 02/07/2020 08/07/2020 Network Rail 02/07/2020 17/07/2020 NORTH KELSEY 02/07/2020 SOUTH KELSEY and 02/07/2020 13/07/2020 MOORTOWN PARISH COUNCIL West Lindsey District Council 02/07/2020 Neighbour List Date Letter Consultation Reply Address Sent Expiry Date Received EASTGATE SMITHFIELD ROAD North Kelsey Moor MARKET RASEN 21/07/2020 LN7 6HG Shepherd's Hill Thorpe Lane Tealby 19/07/2020 LN8 3XJ Smithfield Gatehouse Smithfield Road North Kelsey Moor Market Rasen 07/07/2020 03/07/2020 Lincolnshire LN7 6HG Oakleigh House Caistor Road South 13/07/2020 19/07/2020 Kelsey LN7 6PR The Orangery 5 Manor House 14/07/2020 Gardens Ancaster Avenue LN2 4AY Grasby Parish Council Ash Grove LN8 16/07/2020 3RA Meadowfield Market Rasen Road 14/07/2020 Holton Le Moor LN7 6AE 20 Dudley Street 16/07/2020 Inglenook Enfield Road Donington on 20/07/2020 Bain Louth LN11 9TW Rosegarth Cottage High Streeet West Barn Cottage Caistor Road North -

Unlocking New Opportunies

A 37 ACRE COMMERCIAL PARK ON THE A17 WITH 485,000 SQ FT OF FLEXIBLE BUSINESS UNITS UNLOCKING NEW OPPORTUNIES IN NORTH KESTEVEN SLEAFORD MOOR ENTERPRISE PARK IS A NEW STRATEGIC SITE CONNECTIVITY The site is adjacent to the A17, a strategic east It’s in walking distance of local amenities in EMPLOYMENT SITE IN SLEAFORD, THE HEART OF LINCOLNSHIRE. west road link across Lincolnshire connecting the Sleaford and access to green space including A1 with east coast ports. The road’s infrastructure the bordering woodlands. close to the site is currently undergoing The park will offer high quality units in an attractive improvements ahead of jobs and housing growth. The site will also benefit from a substantial landscaping scheme as part of the Council’s landscaped setting to serve the needs of growing businesses The site is an extension to the already aims to ensure a green environment and established industrial area in the north east resilient tree population in NK. and unlock further economic and employment growth. of Sleaford, creating potential for local supply chains, innovation and collaboration. A17 A17 WHY WORK IN NORTH KESTEVEN? LOW CRIME RATE SKILLED WORKFORCE LOW COST BASE RATE HUBS IN SLEAFORD AND NORTH HYKEHAM SPACE AVAILABLE Infrastructure work is Bespoke units can be provided on a design and programmed to complete build basis, subject to terms and conditions. in 2021 followed by phased Consideration will be given to freehold sale of SEE MORE OF THE individual plots or constructed units, including development of units, made turnkey solutions. SITE BY SCANNING available for leasehold and All units will be built with both sustainability and The site is well located with strong, frontage visibility THE QR CODE HERE ranging in size and use adaptability in mind, minimising running costs from the A17, giving easy access to the A46 and A1 (B1, B2 and B8 use classes). -

Side Roads) Order 2014

THE LINCOLNSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL (A15 LINCOLN EASTERN BYPASS) (CLASSIFIED ROAD) (SIDE ROADS) ORDER 2014 The Lincolnshire County Council (“the Council”) makes this Order in exercise of its powers under Sections 14 and 125 of the Highways Act 1980 and all other powers enabling it in that behalf:- 1. (1) The Council is authorised in relation to the classified roads in the Parish of Greetwell in the District of West Lindsey, the Parish of Canwick, the Parish of Branston and Mere, the Parish of Canwick and the Parish of Bracebridge Heath all in the District of North Kesteven and in the Abbey Ward in the District of Lincoln all in the County of Lincolnshire to:- (i) improve the highways named in the Schedules and shown on the corresponding Site Plan by cross-hatching; (ii) stop up each length of highway described in the Schedules and shown on the corresponding Site Plan by zebra hatching; (iii) construct a new highway along each route whose centre line is shown on a Site Plan by an unbroken black line surrounded by stipple; (iv) stop up each private means of access to premises described in the Schedules and shown on the corresponding Site Plan by a solid black band; (v) provide new means of access to premises along each route shown on a Site Plan by thin diagonal hatching. (2) Where a new highway is to be constructed wholly or partly along the same route as a new access or part of one, that new highway shall be created subject to the private rights over that new access. -

Lincolnshire. [Kelly's

650 l'UB LINCOLNSHIRE. [KELLY'S PUBLICAMS--continued. Indian Queen, George Thomas Lee, 4 Dolphin lane, Boston G-reat Northern inn, T. Plum tree, Seas end,Surfleet,Spalding Ingleby Arms, John Chas. Schacht, Morton, Gainsborough G-reat Northern hotel, Robert Stuart, High street, Lincoln Iron Horse, William Marsden, Gunhouse, Doncaster G-reat Northern, W. Vaughan,Water st.St.Martin's,Stamford Ivy tavern, Joseph Sharp, 51 Newport, Lincoln G-r~t Northern commercial hotel & posting house, John John Bull, Geo. Drewery, The Heath, Hracebridge, Lincoln Hannam, Corby station, Grantham Joiner's Arms, Henry Ogden, Welbourne S.O Great Northern Railway hotel, T. Colton, Station st. Boston Jolly Sailor, James Dyer, 92 Eastgate, Louth Green Dragon, Dickenson Lynn, Swineshead, Boston Jolly Sailors, William Neal, Fishtoft, Boston Green Dragon, Mrs. Betsy Nundy, West Ashby, Horncastle Jolly Scotchman, Henry 'fhompson, Southgate, Sleaford Green Dragon, Robert Reid, Magpies square, Lincoln King's Arms, William Cox, Hurton Pedwardine, Sleaford Green Man, William Baines, 29 Scotgate, Stamford King's Arms, John Holmes, Theatre yard, High st. Lincoln Green Man, Gunthorpe Green, Scamblesby, Horncastle King's Arms, John Clacton Lee, 13 Horncastle road, Boston Green Man, "\Villiam Ureen, Ropsley, Grantham King's Arms, Walker Moody, Haxey, Bawtry Green Man, George Jas. Murrant, Little Bytham, Granthm King's Head, William Baxter, Morton, Bourn Green Man, Christopher Shepherd, Stallingborough, Ulceby King's Head, Samuel Thomas Beales, East end, Alford Green Man, William Templeman, Gosberton, Spalding King's Head, John Hreeton, 16 Bull ring, Horncastle Green Tree, George Pepper, Fen, Branston, Lincoln King's Head, Wm. Burton,sen. North st. -

Polling Districts by LCC Division Feb 2017

NORTH KESTEVEN DISTRICT REGISTRATION AREA LINCOLNSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL - ELECTORAL DIVISIONS FROM MAY 2017– ONE COUNCILLOR PER DIVISION DIVISION NAME DISTRICT WARD NAME PARISH OR TOWN PD CODE WARD NAME BASSINGHAM & BASSINGHAM & BRANT AUBOURN & HADDINGTON BA WELBOURN BROUGHTON (PART) BASSINGHAM BB BECKINGHAM BC BRANT BROUGHTON & BD STRAGGLETHORPE CARLTON LE MOORLAND BE NORTON DISNEY BF SOUTH HYKEHAM BEACON BG STAPLEFORD BJ THURLBY BK CLIFF VILLAGES (PART) BOOTHBY GRAFFOE FA LEADENHAM FD NAVENBY FE WELBOURN FF WELLINGORE FG EAGLE,SWINDERBY & WITHAM WITHAM ST HUGHS GF ST HUGHS (PART) EAGLE & HYKEHAM BASSINGHAM & BRANT SOUTH HYKEHAM CROW BH WEST BROUGHTON (PART) EAGLE, SWINDERBY & WITHAM DODDINGTON & WHISBY GA ST HUGHS (PART) EAGLE & SWINETHORPE GB NORTH SCARLE GC SWINDERBY GD THORPE ON THE HILL GE NORTH HYKEHAM MEMORIAL NORTH HYKEHAM MEMORIAL MD001 & 2 (PART) SKELLINGTHORPE SKELLINGTHORPE PA001 & 2 HECKINGTON BILLINGHAY, MARTIN & NORTH BILLINGHAY AND BILLINGHAY CA001 & 2 KYME (PART) FEN DOGDYKE CB NORTH KYME CD HECKINGTON RURAL BURTON PEDWARDINE HA GREAT HALE HB HECKINGTON EAST HC HECKINGTON WEST HD001 & 2 HELPRINGHAM HE LITTLE HALE HF KIRKBY LA THORPE & SOUTH ANWICK JA KYME ASGARBY & HOWELL JB EWERBY & EVEDON JC KIRKBY LA THORPE JD SOUTH KYME JE OSBOURNBY (PART) SWATON NH HYKEHAM FORUM BASSINGHAM & BRANT SOUTH HYKEHAM DANKER BI BROUGHTON (PART) NORTH HYKEHAM FORUM NORTH HYKEHAM FORUM MA001 & 2 NORTH HYKEHAM MEMORIAL NORTH HYKEHAM POST MILL MF (PART) NORTH HYKEHAM MILL (PART) NORTH HYKEHAM GRANGE MB001 & 2 & 3 NORTH HYKEHAM MOOR NORTH HYKEHAM