2 the Landscape, Its Heritage and Its People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Willow Court, Backbarrow Asking Price £350,000

1 Willow Court, Backbarrow Asking Price £350,000 An exciting opportunity to purchase a detached bungalow set amidst a private gardens and grounds located in the hamlet of Backbarrow near Newby Bridge. The well proportioned property offers a sitting room, dining room, breakfast kitchen, four bedrooms, bathroom, shower room and garage. 1 WILLOW COURT ENTRANCE HALL 23' 6" max x 16' 7" max (7.18m x 5.08m) A well proportioned detached bungalow set amidst Single glazed door with adjacent single glazed window, generous private gardens and grounds within the hamlet of radiator, two built in cupboards, loft access. Backbarrow near Newby Bridge. The location offers easy access to The Swan, The Whitewater and Newby Bridge SITTING/DINING ROOM Hotels, Fell Foot Park and the A590. The amenities 28' 6" max x 11' 10" max (8.69m x 3.62m) available in Bowness, Windermere, Grange-over-Sands, Cartmel village and Ulverston are just a short journey away. SITTING ROOM There are many countryside walks from the doorstep 17' 6" max x 11' 10" max (5.35m x 3.62m) including the Cumbria Coastal Path and Bigland Hall Estate Double glazed French doors, double glazed window, and Tarn. The bungalow is situated on a private lane shared radiator, living flame LPG fire to slate feature fireplace, with three neighbouring properties. recessed spotlights. The well proportioned accommodation briefly comprises of DINING ROOM an entrance hall with cloaks and storage cupboards, sitting 11' 10" x 10' 0" (3.62m x 3.07m) room, dining room, breakfast kitchen, four bedrooms, a Double glazed window, radiator. -

Beatrix Potter Studies

Patron Registered Charity No. 281198 Patricia Routledge, CBE President Brian Alderson This up-to-date list of the Society’s publications contains an Order Form. Everything listed is also available at Society meetings and events, at lower off-the-table prices, and from its website: www.beatrixpottersociety.org.uk BEATRIX POTTER STUDIES These are the talks given at the Society’s biennial International Study Conferences, held in the UK every other year since 1984, and are the most important of its publications. The papers cover a wide range of subjects connected with Beatrix Potter, presented by experts in their particular field from all over the world, and they contain much original research not readily available elsewhere. The first two Conferences included a wide range of topics, but from 1988 they followed a theme. All are fully illustrated and, from Studies VII onwards, indexed. (The Index to Volumes I-VI is available separately.) Studies I (1984, Ambleside), 1986, reprinted 1992 ISBN 1 869980 00 X ‘Beatrix Potter and the National Trust’, Christopher Hanson-Smith ‘Beatrix Potter the Writer’, Brian Alderson ‘Beatrix Potter the Artist’, Irene Whalley ‘Beatrix Potter Collections in the British Isles’, Anne Stevenson Hobbs ‘Beatrix Potter Collections in America’, Jane Morse ‘Beatrix Potter and her Funguses’, Mary Noble ‘An Introduction to the film The Tales of Beatrix Potter’, Jane Pritchard Studies II (1986, Ambleside), 1987 ISBN 1 869980 01 8 (currently out of print) ‘Lake District Natural History and Beatrix Potter’, John Clegg ‘The Beatrix -

Kendal • Croftlands • Ulverston • Barrow from 23 July 2018 Journeys from Kendal & Windermere Towards Barrow Will Operate Via Greenodd Village 6 X6

Kendal • Croftlands • Ulverston • Barrow From 23 July 2018 journeys from Kendal & Windermere towards Barrow will operate via Greenodd village 6 X6 Monday to Saturday excluding Public Holidays Sunday and Public Holidays route number 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 route number 6 6 6 X6 6 X6 6 X6 6 X6 6 6 6 6 6 journey codes mf l mf l mf mf s sfc v v journey codes v v v v Kendal Bus Station Stand C - - - - - - - 0700 - - 0800 - - 0900 - - 1000 - - - 1100 - - 1200 - - 1300 - Kendal Bus Station Stand C - - - 1130 - 1330 - 1530 - 1730 - - - - - Kendal College - - - - - - - 0705 - - 0805 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - K Village - - - 1133 - 1333 - 1533 - 1733 - - - - - K Village - - - - - - - - - - - - - 0905 - - 1005 - - - 1105 - - 1205 - - 1305 - Helsington Lumley Road - - - 1135 - 1335 - 1535 - 1735 - - - - - Helsington Lumley Road - - - - - - - 0708 - - 0808 - - 0908 - - 1008 - - - 1108 - - 1208 - - 1308 - Heaves Hotel A590 Levens - - - 1141 - 1341 - 1541 - 1741 - - - - - Heaves Hotel A590 Levens - - - - - - - 0714 - - 0814 - - 0914 - - 1014 - - - 1114 - - 1214 - - 1314 - Witherslack Road End - - - 1147 - 1347 - 1547 - 1747 - - - - - Witherslack Road End - - - - - - - 0720 - - 0820 - - 0920 - - 1020 - - - 1120 - - 1220 - - 1320 - Lindale Village - - - 1151 - 1351 - 1551 - 1751 - - - - - Lindale Village - - - - - - - 0724 - - 0824 - - 0924 - - 1024 - - - 1124 - - 1224 - - 1324 - Grange Rail Station - - - 1157 - 1357 - 1557 - 1757 - - - - - Grange Rail Station - - - - - - - 0730 - - 0830 - - 0930 - - 1030 -

Grizedale Forest

FORESTRY COMMISSION H.M. Forestry Commission GRIZEDALE FOREST FOR REFERENCE ONLY NWCE)CONSERVANCY Forestry Commission ARCHIVE LIBRARY 1 I.F.No: H.M. Forestry Commission f FORESTRY COMMISSION HISTORY o f SHIZEDALE FOREST 1936 - 1951 NORTH WEST (ENGLAND) CONSERVANCY HISTORY OF GRIZEDALE FOREST Contents Page GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE FOREST ...................... 1 Situation ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• 1 Ax*ea ancL Utilisation • • • ••• ••• ••• • • • 1 Physiography * *. ••• ... ••• ••• 4 Geology and Soils ... ... ... ... ... 5 Vegetation ... ... ... ... ••• 6 Meteorology ... •.• ••• ••• 6 Risks ••• • • • ••• ... ••• 7 Roads * • # ••• • • • ••• ••• 8 Labour .«• .«• ... .•• ••• 8 SILVICULTURE ••• * • • ••• ••• ••• 3 Preparation of Ground ... ... ... ... ... 3 t Choice of Species ... ... ... ... ... 9 Planting - spacing, types of plants used, Grizedale forest nursery, method of planting, annual rate of planting, manuring, success of establishment ... 11 Ploughing ... ... ... ... ... 13 Beating up ... ... ... ... ... li^ Weeding ... ... ... ... ... 14 Mixture of Species ... ... ... ... ... 14 Rates of Growth ... ... ... ... ... 13 Past treatment of established plantations Brashing, pruning, cleaning and thinning ... 17 Research ... ... ... ... ... 21 Conclusions ... ... ... ... ... 21 Notes by State Forests Officer ... ... ... ... 23 APPENDICES I Notes from Inspection Reports ... ... 24 II Record of Supervisory Staff ... ... 26 III Other notes of interest 1) Coppice demonstration area ... ... 27 2) Headquarters seed store ... ... 27 Map of the Forest HISTORY OF GRIZEDALE FOREST GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE FOREST Situation The forest is situated in the Furness Fells area of Lancashire between the waters of Coniston and Esthwaite. It lies within the Lake District National Park area, and covers a total of 5,807 acres. The name Grizedale is derived from the name given to the valley by the Norse invaders, who in the ninth century, colonised Furness and its Fells. At the heads of the high valleys, the then wild forest land was used for the keeping of pigs. -

2951 20 January 2021

Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North West of England) Notices and Proceedings Publication Number: 2951 Publication Date: 20/01/2021 Objection Deadline Date: 10/02/2021 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North West of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 20/01/2021 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. At the moment we cannot be reached by phone. -

Levens Hall & Gardens

LAKE DISTRICT & CUMBRIA GREAT HERITAGE 15 MINUTES OF FAME www.cumbriaslivingheritage.co.uk Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal Cumbria Living Heritage Members’ www.abbothall.org.uk ‘15 Minutes of Fame’ Claims Cumbria’s Living Heritage members all have decades or centuries of history in their Abbot Hall is renowned for its remarkable collection locker, but in the spirit of Andy Warhol, in what would have been the month of his of works, shown off to perfection in a Georgian house 90th birthday, they’ve crystallised a few things that could be further explored in 15 dating from 1759, which is one of Kendal’s finest minutes of internet research. buildings. It has a significant collection of works by artists such as JMW Turner, J R Cozens, David Cox, Some have also breathed life into the famous names associated with them, to Edward Lear and Kurt Schwitters, as well as having a reimagine them in a pop art style. significant collection of portraits by George Romney, who served his apprenticeship in Kendal. This includes All of their claims to fame would occupy you for much longer than 15 minutes, if a magnificent portrait - ‘The Gower Children’. The you visited them to explore them further, so why not do that and discover how other major piece in the gallery is The Great Picture, a interesting heritage can be? Here’s a top-to-bottom-of-the-county look at why they triptych by Jan van Belcamp portraying the 40-year all have something to shout about. struggle of Lady Anne Clifford to gain her rightful inheritance, through illustrations of her circumstances at different times during her life. -

The Journal of the Fell & Rock Climbing Club

THE JOURNAL OF THE FELL & ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT Edited by W. G. STEVENS No. 47 VOLUME XVI (No. Ill) Published bt THE FELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT 1953 CONTENTS PAGE The Mount Everest Expedition of 1953 ... Peter Lloyd 215 The Days of our Youth ... ... ...Graham Wilson 217 Middle Alps for Middle Years Dorothy E. Pilley Richards 225 Birkness ... ... ... ... F. H. F. Simpson 237 Return to the Himalaya ... T. H. Tilly and /. A. ]ac\son 242 A Little More than a Walk ... ... Arthur Robinson 253 Sarmiento and So On ... ... D. H. Maling 259 Inside Information ... ... ... A. H. Griffin 269 A Pennine Farm ... ... ... ... Walter Annis 275 Bicycle Mountaineering ... ... Donald Atkinson 278 Climbs Old and New A. R. Dolphin 284 Kinlochewe, June, 1952 R. T. Wilson 293 In Memoriam ... ... ... ... ... ... 296 E. H. P. Scantlebury O. J. Slater G. S. Bower G. R. West J. C. Woodsend The Year with the Club Muriel Files 303 Annual Dinner, 1952 A. H. Griffin 307 'The President, 1952-53 ' John Hirst 310 Editor's Notes ... ... ... ... ... ... 311 Correspondence ... ... ... ... ... ... 315 London Section, 1952 316 The Library ... ... ... ... ... ... 318 Reviews ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 319 THE MOUNT EVEREST EXPEDITION OF 1953 — AN APPRECIATION Peter Lloyd Everest has been climbed and the great adventure which was started in 1921 has at last been completed. No climber can fail to have been thrilled by the event, which has now been acclaimed by the nation as a whole and honoured by the Sovereign, and to the Fell and Rock Club with its long association with Everest expeditions there is especial reason for pride and joy in the achievement. -

7. Industrial and Modern Resource

Chapter 7: Industrial Period Resource Assessment Chapter 7 The Industrial and Modern Period Resource Assessment by Robina McNeil and Richard Newman With contributions by Mark Brennand, Eleanor Casella, Bernard Champness, CBA North West Industrial Archaeology Panel, David Cranstone, Peter Davey, Chris Dunn, Andrew Fielding, David George, Elizabeth Huckerby, Christine Longworth, Ian Miller, Mike Morris, Michael Nevell, Caron Newman, North West Medieval Pottery Research Group, Sue Stallibrass, Ruth Hurst Vose, Kevin Wilde, Ian Whyte and Sarah Woodcock. Introduction Implicit in any archaeological study of this period is the need to balance the archaeological investigation The cultural developments of the 16th and 17th centu- of material culture with many other disciplines that ries laid the foundations for the radical changes to bear on our understanding of the recent past. The society and the environment that commenced in the wealth of archive and documentary sources available 18th century. The world’s first Industrial Revolution for constructing historical narratives in the Post- produced unprecedented social and environmental Medieval period offer rich opportunities for cross- change and North West England was at the epicentre disciplinary working. At the same time historical ar- of the resultant transformation. Foremost amongst chaeology is increasingly in the foreground of new these changes was a radical development of the com- theoretical approaches (Nevell 2006) that bring to- munications infrastructure, including wholly new gether economic and sociological analysis, anthropol- forms of transportation (Fig 7.1), the growth of exist- ogy and geography. ing manufacturing and trading towns and the crea- tion of new ones. The period saw the emergence of Environment Liverpool as an international port and trading me- tropolis, while Manchester grew as a powerhouse for The 18th to 20th centuries witnessed widespread innovation in production, manufacture and transpor- changes within the landscape of the North West, and tation. -

19. South Cumbria Low Fells Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 19. South Cumbria Low Fells Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 19. South Cumbria Low Fells Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper 1, Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention3, we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are North areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines East in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape England our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics London and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are South East suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance South West on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

Colton Community Plan 2015

COLTON COMMUNITY PLAN 2015 Main photo: Rusland valley looking west towards the Coniston Fells. © Teresa Morris Map: Ordnance Survey. © Crown Copyright 2005 Colton Parish Community Plan 2015 Introduction Topics, Policies and Actions 1. The Local Economy 2. Landscape and the Natural Environment 3. Communities and Well-Being 4. Housing and Other Development 5. Roads, Traffic and Transport 6. Energy and Sustainability Annexes Annex A: Community Plan Working Group Members Annex B: Action Plan Annex C: Community Transport Schemes Map of Colton Parish (back page) 1 Introduction Purpose Community Plans set out the issues that local people value about their neighbourhoods, and their aspirations for the future. They tend to be based on civil parish areas (like Colton) or groups of parishes. It is essential that that such Plans properly reflect the values, opinions, needs and aspirations of the community, and that they should be community-led, facilitated by the Parish Council. Principal authorities (in Colton’s case: Cumbria County Council and South Lakeland District Council) and planning authorities (in Colton’s case: the Lake District National Park Authority), are increasingly using these Plans to guide local policy and inform planning decisions. The purpose of this Plan is to set out policies and action plans for the future of the Parish. To this end, invitations to join a Community Plan Working Group brought together people from all three wards of our large rural parish, including parish councillors and the parish clerk. Working group members and contributors are listed in Annex A. Background Colton Civil Parish is a sparsely populated rural area of about 20 square miles within the southern part of the Lake District National Park, spanning three valleys running north-south: Coniston Water and the Crake Valley to the west, Rusland in the centre and Windermere and the River Leven in the east. -

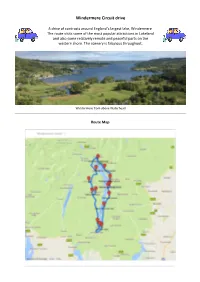

Windermere Circuit Drive

Windermere Circuit drive A drive of contrasts around England’s largest lake, Windermere. The route visits some of the most popular attractions in Lakeland and also some relatively remote and peaceful parts on the western shore. The scenery is fabulous throughout. Windermere from above Waterhead Route Map Summary of main attractions on route (click on name for detail) Distance Attraction Car Park Coordinates 0 miles Waterhead, Ambleside N 54.42116, W 2.96284 2.1 miles Brockhole Visitor Centre N 54.40120, W 2.93914 4.3 miles Rayrigg Meadow picnic site N 54.37897, W 2.91924 5.3 miles Bowness-on-Windermere N 54.36591, W 2.91993 7.6 miles Blackwell House N 54.34286, W 2.92214 9.5 miles Beech Hill picnic site N 54.32014, W 2.94117 12.5 miles Fell Foot park N 54.27621, W 2.94987 15.1 miles Lakeside, Windermere N 54.27882, W 2.95697 15.9 miles Stott Park Bobbin Mill N 54.28541, W 2.96517 21.0 miles Esthwaite Water N 54.35029, W 2.98460 21.9 miles Hill Top, Near Sawrey N 54.35247, W 2.97133 24.1 miles Hawkshead Village N 54.37410, W 2.99679 27.1 miles Wray Castle N 54.39822, W 2.96968 30.8 miles Waterhead, Ambleside N 54.42116, W 2.96284 The Drive Distance: 0 miles Location: Waterhead car park, Ambleside Coordinates: N 54.42116, W 2.96284 Slightly south of Ambleside town, Waterhead has a lovely lakeside setting with plenty of attractions. Windermere lake cruises call at the jetty here and it is well worth taking a trip down the lake to Bowness or even Lakeside at the opposite end of the lake. -

Colton Parish Plan 2003 Page 1 1.1

ColtonColton The results of a community consultation 2003 Parish Plan •Lakeside •Finsthwaite •Bouth •Oxen Park •Rusland •Nibthwaite ContentsContents 1. Foreword . .2 5. Summary of Survey Results . .28 - 30 by the Chairman of the Parish Council Analysis of the AHA report on the Questionnaire 2. Introduction and Policy . .3 6. Residents comments from questionnaire . .31 - 33 3. The Parish of Colton . .4 7. The Open Meetings Brief . .34 report on the three open meetings held and comments and points 4. Response from Organisations and Individuals . .5 raised at the meetings Information provided by various organisations Rusland & District W.I. .5 8. Action Plan . .35 - 37 Bouth W.I. .6 Young Farmers . .7-8 9. Vision for the Future . .38 Holy Trinity Parish Church Colton . .9 Saint Paul’s Parish Church, Rusland . .10 10. Colton Parish Councillors . .39 Tottlebank Baptist Church . .11 Rookhow Friends Meeting house in the Rusland Valley . .12 11. Appendix . .40 Finsthwaite Church . .13 Copy of the Parish Plan Questionnaire Response from Schools . .14 - 15 A Few of the Changes in Fifty Years of Farming . .16 - 17 National Park Authority owned properties in Colton Parish . .18 Response from the Lake District National Park Authority . .19 Response from Cumbria County Council . .19 South Lakeland District Council . .20 Rusland Valley Community Trust . .21 Forest Enterprise . .22 Hay Bridge Nature Reserve . .23 Lakeside & Finsthwaite Village Hall . .24 Rusland Reading Rooms . .25 Bouth Reading Rooms . .25 Oxen Park Reading Room . .25 Rusland Valley Horticultural Society . .26 - 27 Colton Parish Plan 2003 Page 1 1.1. ForewordForeword Colton Parish is one of the larger rural generally.