Full Biography of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 5, 2020 COME WORSHIP with US MASSES, CONFESSIONS, and EUCHARISTIC EXPOSITION MASS CHANGES ARE in RED WEEKLY CALENDAR

Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church 10700 ABOITE CENTER ROAD ~ FORT WAYNE INDIANA 46804 ~ (260) 432-0268 Fr. Dave Voors, Pastor ~ Fr. Louis Fowoyo, Parochial Vicar ~ Fr. Thomas Zehr, Parochial Vicar www.seasfw.org ~ www.facebook.com/SEASFW ~ [email protected] SCHOOL: Lois Widner, Principal (260) 432-4001 ~ www.seascsfw.org Where is the newborn king of the Jews? We saw his star at its rising And have come to do him homage. Matthew 2:2 January 5, 2020 COME WORSHIP WITH US MASSES, CONFESSIONS, AND EUCHARISTIC EXPOSITION MASS CHANGES ARE IN RED WEEKLY CALENDAR Monday, January 6 St. Andre Bessette, Religious Sunday, January 5 1 Jn 3:22—4:6/Ps 2:7bc-8, 10-12a/Mt 4:12-17, 23-2 Nursery Open for 9:30 and 11:30 am Masses 9:00 am † Ray Jones 9:30 am Breaking Open the Word-RCIA, Mother Seton 5:45 pm Reconciliation until 6:10 pm 12:30 pm CYO Sports, PAC 6:30 pm † Robert Schmidt 12:45 pm Server Training, Church 1:00 pm CRHP Continuation Committee, Mother Teresa Tuesday, January 7 St. Raymond of Penyafort, Priest 2:45 pm Contemporary Choir, Church 1 Jn 4:7-10/Ps 72:1-2, 3-4, 7-8/Mk 6:34-4 6:30 am † Louis Coronato Monday, January 6 7:00 am Eucharistic Exposition until 6:00 pm 9:00 am Parish Office Open until 4:30 pm 9:30 am Mary & Martha Lds. Group, Fr. Solanus 9:00 am Fr. Dave Voors 6:30 pm RCIA, Mother Teresa 7:00 pm Pro-Life Meeting, Fr. -

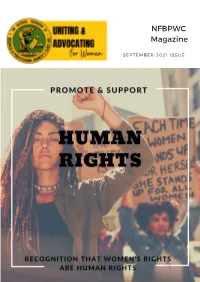

NFBPWC Magazine

NFBPWC Magazine SEPTEMBER 2021 ISSUE September 2021 Newsletter In This Issue About NFBPWC 2 President’s Message – Megan Shellman-Rickard 3 National BPW Events BPW International President’s Message 4 Membership News – Kathy Kelly 5 Fridays, September 3, 10, 17 and 24, 2021 Intern Blog Series by Bryn Norrie 5 NFBPWC National Friday Conversations Virtual Club | NFBPWC Benefits 6 Register: https://www.nfbpwc.org/events A Celebration of Life – Toni Torres 7 Advocacy Report – Daneene Rusnak 8 Last Tuesday of Each Month Team ERA Report – Nancy Werner 10 Membership Committee Meeting Team LGBTQ+ Report – Susan Oser 11 Register: https://www.nfbpwc.org/events Secretary Letter – Barbara Bozeman 12 Treasurer’s Report – Deborah Fischer 14 Wednesday, September 15, 2021 “Imposter Syndrome: Is it Me? / Is it Them?” Guest Young BPW – Ashley Maria 15 Speaker Monica Monroe Environment Report – Hyon Rah 15 NFBPWC Virtual Chapter hosting Bring Back the Pollinators – Marikay Shellman 17 4:00 PM Pacific | 5:00 PM Mountain | 6:00 PM Health Committee Report – Keri Hess 18 Central | 7:00 PM Eastern Lifelong Leadership & Learning Report – Kathy Telban 18 Register: https://www.nfbpwc.org/event-4371113 Mentoring Committee Report – Dr. Trish Knight 18 Small Business Committee – Manjul Batra 19 United Nations Report – Susan O’Malley 19 Digital Training – Marsha Riibner-Cady & Judy Bell 21 Regional BPW Events Website Committee Report – Lea-Ann W. Berst 21 Social Media Committee – Susan Oser 22 Thursday, September 16, 2021 “Goal Setting is a Powerful Motivator,” State -

Steve and Janet Ray's Biography

STEVE AND JANET RAY’S BIOGRAPHY Steve and Janet Ray in Jerusalem—they have been to the Holy Land over 170 times Steve’s first book—his conversion story EARLY YEARS CONVERSION PUBLISHED BOOKS Stephen K. Ray was born in 1954 to parents Prior to 1994, neither Steve or Janet had Crossing the Tiber who had just become Christians through a ever set foot in a Catholic Church. After (conversion story) Billy Graham Crusade. studying many books to convince their best friend and recent convert, Al Kresta, that He was raised in a Fundamentalist Baptist Upon this Rock: the early church was evangelical, Steve family and was dedicated to Jesus in the Peter and the Primacy of Rome and Janet backed their way right into the local Baptist Church. At four years old he Catholic Church. “asked Jesus into his heart” and was “born St. John’s Gospel again” according to Baptist tradition. On Pentecost Sunday, 1994, they entered (a Bible Study) the Church at Christ the King Parish in Ann In 1976, Stephen married Janet who Arbor, Michigan. The Papacy: came from a long line of Protestants. Her What the Pope Does and Why it ancestors were pilgrims who came to Steve began writing a letter to his father Matters America on the Mayflower and Moravian explaining why they became Catholic. This Hussite Protestants who joined the letter soon became the book Crossing the Faith for Beginners: Protestant Reformation in the 1600s. Tiber: Evangelical Protestants Discover the A Study of the Creeds Historic Church, published by Ignatius Press. EXPLORING THEIR FOOTPRINTS OF GOD PROTESTANT ROOTS DVD SERIES CURRENT With two small children in tow, Steve and Janet moved to Europe for one year where Since then, Steve’s passion for the depth Abraham: Father of Faith they traveled extensively researching their of truth found within the Catholic tradition and Words reformation roots in Switzerland, Germany, has led him to walk away from his business Moses: Signs, Sacraments, and England. -

The Biographical Turn and the Case for Historical Biography

DOI: 10.1111/hic3.12436 ARTICLE The biographical turn and the case for historical biography Daniel R. Meister Department of History, Queen's University Abstract Correspondence Daniel R. Meister, Department of History, Biography has long been ostracized from the academy while Queen's University, Canada. remaining a popular genre among the general public. Recent height- Email: [email protected] ened interest in biography among academics has some speaking of a Funding information biographical turn, but in Canada historical biography continues to be International Council for Canadian Studies, undervalued. Having not found a home in any one discipline, Biog- Grant/Award Number: Graduate Student Scholarship (2017); Social Sciences and raphy Studies is emerging as an independent discipline, especially Humanities Research Council of Canada, in the Netherlands. This Dutch School of biography is moving biog- Grant/Award Number: 767‐2016‐1905 raphy studies away from the less scholarly life writing tradition and towards history by encouraging its practitioners to utilize an approach adapted from microhistory. In response to these develop- ments, this article contends that the discipline of history should take concrete steps to strengthen the subfield of Historical Biography. It further argues that works written in this tradition ought to chart a middle path between those studies that place undue focus on either the individual life or on broader historical questions. By employing a critical narrative approach, works of Historical Biography will prove valuable to both academic and non‐academic readers alike. The border separating history and biography has always been uncertain and anything but peaceful. (Loriga, 2014, p. 77) Being in the midst of a PhD dissertation that has its roots in extensive biographical research, I was advised to include in my introduction an overview of theoretical approaches to biography. -

Louise De Marillac and the Spirituality of the Daughters of Charity

Vincentiana, July-September 2012 Louise de Marillac and the Spirituality of the Daughters of Charity Meeting of Provincial Directors Sr. Antoinette Marie Hance, D.C. Introduction Louise de Marillac is an extraordinary woman and a great mystic, and to speak of her and her spirituality is, in a certain sense, to marvel anew at God’s loving plan for humanity, for the Church, for persons living in poverty, and for God’s preference for the lowly and humble of heart. Yes, God always surprises us, and in taking a new look at the life of Louise de Marillac, and dwelling on the spirituality shared with the fi rst Sisters, we see how God constantly borrows from our ways to reveal His love. I’m going to begin by letting St. Vincent speak. On July 24, 1660, two months before his death, he exhorted the fi rst Sisters as follows: “Sisters, after the example of your good mother, take the resolution to work at becoming holy and to detach yourselves from what displeases God in you” 1 . “After the example of your good Mother”. I think that looking at Louise to learn from her how to work at making ourselves holy according to God’s plan for us, and to detach ourselves from what displeases God, is characteristic of a spirituality: proposing a special path of holiness, a particular way of following Christ. The 350th anniversary of the deaths of Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac was certainly a special opportunity to discover Louise or to get to know her better. -

Vincentian II

Topic 20: Vincentian Spirituality: Practical Charity, Part 2 Overview: St. Louise de Marillac became a companion to St. Vincent. They complemented each other with two very different personalities and skill-sets. Louise was the head person while Vincent was the heart person. What they shared in common was conversion of heart that came through the experience of the poor. Together, they founded of the Daughters of Charity, a radical break with previous forms of religious life for women. The Daughters became “Nuns in the World,” and they became the model for all subsequent forms of active religious life for women. Elizabeth Ann Seton brought the spirit and way of life of Vincent and Louise to America. She founded the Sisters of Charity, who expressed the virtue of charity through education, especially of the poor, ignorant, and immigrants. Louise de Marillac • Louise came into Vincent’s life after his conversion. • Louise’s early life was troubled. She never knew her mother. Her health was fragile. Her husband died in 1625 after a prolonged illness. The limitations of her childhood were always a source of anguish for her. This series of experiences plunged her into a dark night of the soul. • Vincent became a spiritual guide for her in dealing with her discouragement. Her friendship and collaboration with Vincent became a healing force in her life. Vincent was always there to support her through trials and tribulations. • Vincent helped her to become less reasoned and more spontaneous. • Her service to the poor and involvement with the Confraternities of Charity gradually cured her depressed spirit. -

New Jersey Catholic Records Newsletter, Vol. 11, No.2 New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission Archives and Special Collections newsletters Winter 1992 New Jersey Catholic Records Newsletter, Vol. 11, No.2 New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/njchc Part of the History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission, "New Jersey Catholic Records Newsletter, Vol. 11, No.2" (1992). New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission newsletters. 32. https://scholarship.shu.edu/njchc/32 NEW JERSEY faJJwIi.c Jiii}uriaJ RECORDS COMMISSION S l TUN ~i A LL U l'\j IV t: R S I TY VOLUME XI NO.2 WINTER 1992 Thus it was that Newark's frrst Saint Michael's Medical Center, Newark: hospitals opened in the aftermath of the war. St Barnabas, affiliated with the 125 Episcopal Church, began receiving patients in a private house in 1865. Some years ofNewark's residents ofGerman descent began work toward a facility for their of service fellow-Germans, which opened in 1870 as German Hospital. Between these two, to the Newark's Catholics started what became community Saint Michael's Hospital. Catholic interest in serving the sick poor manifested itself earliest, perhaps, in the wishes ofNicholas Moore, who left money in his will to found a hospital and Saint Michael's as the building appeared in 1871 asylum. Father John M. Gervais, pastor of S1. James Church and executor of the "The Sisters of the Poor are fully south. The swelling population over will, provided some service for the sick established and have a gem of a hospital, whelmed the primitive social welfare poor through the S1. -

Pentecost Experience of Saint Louise De Marillac

Pentecost Experience of Saint Louise de Marillac In the year 1623, on the Feast of Saint Monica, God gave me the grace to make a vow of widowhood should He call my husband to Himself. On the following Feast of the Ascension, I was very disturbed because of the doubt I had as to whether I should leave my husband, as I greatly wanted to do, in order to make good my first vow(note 1) and to have greater liberty to serve God and my neighbor. I also doubted my capacity to break the attachment I had for my director(2) which might prevent me from accepting another, during his long absence, as I feared I might be obliged to do. I also suffered greatly because of the doubt I experienced concerning the immortality of the soul. All these things caused me incredible anguish which lasted from Ascension until Pentecost. On the Feast of Pentecost(3) during holy Mass or while I was praying in the church(4), my mind was instantly freed of all doubt. I was advised that I should remain with my husband and that a time would come when I would be in a position to make vows of poverty, chastity and obedience and that I would be in a small community where others would do the same. I then understood that I would be in a place where I could help my neighbor but I did not understand how this would be possible since there was to be much coming and going. I was also assured that I should remain at peace concerning my director; that God would give me one(5) whom He seemed to show me. -

St. Vincent De Paul and the Homeless

WELCOMING THE STRANGER ST. VINCENT DE PAUL AND THE HOMELESS Robert Maloney, CM An earlier version of this article was published in Vincentiana 61, #2 (April-June 2017) 270-92. “There was no room for them in the inn.”1 Those stark words dampen the joy of Luke’s infancy narrative, which we read aloud every Christmas. No room for a young carpenter and his pregnant wife? Was it because they asked for help with a Galilean accent that identified them as strangers?2 Was there no room for the long-awaited child at whose birth angels proclaimed “good news of great joy that will be for all people”?3 No, there was no room. Their own people turned Mary and Joseph away. Their newborn child’s first bed was a feeding trough for animals. Matthew, in his infancy narrative, recounts another episode in the story of Jesus’ birth, where once again joy gives way to sorrow.4 He describes the death-threatening circumstances that drove Joseph and Mary from their homeland with Jesus. Reflecting on this account in Matthew’s gospel, Pius XII once stated, “The émigré Holy Family of Nazareth, fleeing into Egypt, is the archetype of every refugee family." 5 Quoting those words, Pope Francis has referred to the plight of the homeless and refugees again and again and has proclaimed their right to the “3 L’s”: land, labor and lodging.6 Today, in one way or another, 1.2 billion people share in the lot of Joseph, Mary and Jesus. Can the Vincentian Family have a significant impact on their lives? In this article, I propose to examine the theme in three steps: 1. -

Medieval Biography Between the Individual and the Collective

Janez Mlinar / Medieval Biography Between the individual and the ColleCtive Janez Mlinar Medieval Biography between the Individual and the Collective In a brief overview of medieval historiography penned by Herbert Grundmann his- torical writings seeking to present individuals are divided into two literary genres. Us- ing a broad semantic term, Grundmann named the first group of texts vita, indicating only with an addition in the title that he had two types of texts in mind. Although he did not draw a clear line between the two, Grundmann placed legends intended for li- turgical use side by side with “profane” biographies (Grundmann, 1987, 29). A similar distinction can be observed with Vollmann, who distinguished between hagiographi- cal and non-hagiographical vitae (Vollmann, 19992, 1751–1752). Grundmann’s and Vollman’s loose divisions point to terminological fluidity, which stems from the medi- eval denomination of biographical texts. Vita, passio, legenda, historiae, translationes, miracula are merely a few terms signifying texts that are similar in terms of content. Historiography and literary history have sought to classify this vast body of texts ac- cording to type and systematize it, although this can be achieved merely to a certain extent. They thus draw upon literary-historical categories or designations that did not become fixed in modern languages until the 18th century (Berschin, 1986, 21–22).1 In terms of content, medieval biographical texts are very diverse. When narrat- ing a story, their authors use different elements of style and literary approaches. It is often impossible to draw a clear and distinct line between different literary genres. -

Seton Hall Physical Therapist Leads Football Star Eric Legrand's Recovery Invented Here

SFall 2013 ETON HA homeALL for the mind, the heart and the spirit Love Connectionsh ALSO: SETON HALL PHYSICAL THERAPIST LEADS FOOTBALL STAR ERIC LEGRAND’S RECOVERY INVENTED HERE: ALUMNI SOLVE TOUGH PROBLEMS THROUGH INGENUITY SETON HALL Fall 2013 Vol. 24 Issue 2 Seton Hall magazine is published by In this issue the Department of Public Relations and Marketing in the Division of University Advancement. President A. Gabriel Esteban, Ph.D. features Vice President for University Advancement 20 Seton Hall David J. Bohan, M.B.A. Love Connections Associate Vice President for Public Relations and Marketing Dan Kalmanson, M.A. 25 Passion Ingenuity Director of Publications/ + University Editor Breakthroughs Pegeen Hopkins, M.S.J. = Seton Hall inventors use creativity Art Director to solve thorny problems. Elyse M. Carter Design and Production Linda Campos Eisenberg departments 20 Photographer Milan Stanic ’11 2 From Presidents Hall Copy Editor Kim de Bourbon 4 HALLmarks Assistant Editor Possibilities A Spiritual Erin Healy 12 Connection Despite a busy medical practice, News & Notes Editors pediatrician Michael Giuliano has Finding peace Dan Nugent ’03 embarked on a spiritual journey Kathryn Moran ’12 to become a deacon. and tranquility in the Chapel of Contributing HALLmarks Writer Roaming the Hall Susan Alai ’74 14 the Immaculate Yanzhong Huang, one of the world’s Send your comments and suggestions top experts in global health, has Conception. by mail to: Seton Hall magazine, been exceptional from the start. Department of Public Relations and Marketing, 457 Centre Street, South Orange, NJ 07079; by email 16 Profile 25 to [email protected]; or by phone Physical Therapist Sandra “Buffy” at 973-378-9834. -

St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church

St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church 1835 Larkvane Road ● Rowland Heights, CA 91748-2503 Rev. John H. Keese Pastor Rev. Miguel Ángel Ruiz Associate Pastor Rev. Dominic Su Associate Pastor Rev. Michael Barry, SS.CC. Auxiliary Priest Steve Hillmann Deacon Peter Chu Deacon Ray Gallego Deacon Fe Musgrave Pastoral Associate Jo Anne Barce Business Manager ______________________________________________________________________________ SUNDAY MASSES Vigil (Saturday): 5:00 p.m. 6:45 a.m., 9:30 a.m., 11:00 a.m., 12:30 p.m. & 5:30 p.m. Spanish / Español: 8:00 a.m. Chinese: 3:30 p.m. PARISH CENTER Office Phone: (626) 964-3629 ● Fax: (626) 913-2209 ● Email: [email protected] Website: www.seasrh.org Office Hours: Monday-Friday: 9:00 a.m.-8:30 p.m.● Saturday: 9:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m. ● Sunday: 9:00 a.m.-2:00 p.m. OFFICE OF RELIGIOUS EDUCATION Office Phone: (626) 965-5792 ● Fax: (626) 913-0580 ● Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday-Thursday: 12:00 p.m.-7:30 p.m. ● Friday-Sunday: CLOSED Coordinator of Religious Education: Suzann Oseguera ● Email: [email protected] Coordinator of Confirmation: Myron Villanueva ● Cell /Text: (626) 536-2153 ● Email: [email protected] Page 2 ● St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church ● January 05, 2020 LITURGY, SPIRITUALITY & PARISH NEWS SAINT ELIZABETH TODAY’S READINGS ANN SETON First Reading — Rise up in splendor, Jerusalem! The Lord shines upon you and the glory of the Lord appears over you (1774-1821) (Isaiah 60:1-6). January 4 Psalm — Lord, every nation on earth will adore you (Psalm 72).