Jessica Eaton and Erin Shirreff's Counterpoints of View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Please Click Here to View the Conference

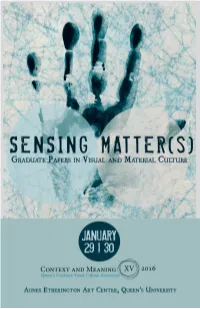

Queen’s University Presents: _____________________________________________________________________ Context and Meaning XV: Sensing Matters(s) _____________________________________________________________________ Papers in Visual and Material Culture and Art Conservation January 29th – January 30th, 2016 Agnes Etherington Art Centre Kingston, Ontario ___________________________________________________ About the Conference ___________________________________________________ The GVCA’s annual graduate student conference, Context and Meaning, is in its fifteenth year. The primary focus of the conference has been the consideration of how art and context come together to produce meaning. For the past three years, the decision was made to introduce a more defined theme, beginning with “Making and Breaking Identity,” “Contact,” and last year’s “Ideolog(ies).” These themes allowed for a focused yet inclusive forum that facilitated discussion while encompassing a range of topics. We hope to achieve the same success this year with “Sensing Matter(s).” This conference is intended to have a wide reach. It is open to both historical and contemporary topics, both discussions of “fine art” objects and those encountered every day. This year, we encouraged submissions from a range of disciplines that deal with the study of visual and material culture. We believe that we have achieved our goal and look forward to engaging discussions that reveal commonalities between seemingly disparate subjects. ___________________________________________________ About the GVCA ___________________________________________________ The Graduate Visual Culture Association (GVCA) was formed in 2003 to enhance the quality of graduate student life in the Department of Art at Queen’s University. The GVCA has flourished through the active participation of new and returning graduate students and through social events and regular academic activities in the Department of Art. -

Contemporary Art Series California Museum of Photography at UCR Artsblock

3834 Main Street California Museum of Photography Riverside, CA 92501 Sweeney Art Gallery 951.827.3755 Culver Center of the Arts culvercenter.ucr.edu sweeney.ucr.edu University of California, Riverside cmp.ucr.edu artsblock.ucr.edu PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release FLASH! contemporary art series California Museum of Photography at UCR ARTSblock RIVERSIDE, Calif., Aug 10, 2013 – UCR ARTSblock announces the contemporary art series FLASH! which features new photography-based work by artists in all stages of their careers. The projects, about five per year, are presented in a small gallery on the third floor of the California Museum of Photography at UCR ARTSblock. The series is organized by Joanna Szupinska-Myers, CMP Curator of Exhibitions. Each exhibition is accompanied by an original essay, available to visitors in the form of a gallery guide. The inaugural project, Flash: Amir Zaki (June 1–July 27, 2013) was the presentation of a single photograph from the artist’s recent series “Time moves still.” Tree Portrait #16 (2012), composited from dozens of smaller photographs, depicts a carefully framed treetop, the body of its trunk disappearing beyond the edge of the frame. The many image-captures used to make this photograph afford the subject an uncanny level of detail; the work evokes at once a sense of stillness and movement. Zaki has an ongoing interest in the rhetoric of authenticity as it relates to photography as an indexical medium, and is committed to exploring the transformative potential of digital technology to disrupt that presumed authenticity. Zaki is an artist who lives and works in Southern California. -

Canadian Excellence, Global Recognition: Canada's 2019 Winners of Major International Research Awards

Canadian excellence, global recognition: Canada’s 2019 winners of major international research awards Meet international award winners from previous years at: www.univcan.ca/globalexcellence I am thrilled to be part of a publication that celebrates the successes of Canada’s research community. As we marvel at Celebrating 2019’s stellar research accomplishments, let’s make this an opportunity to spark a much-needed conversation on the Canadian importance of cultivating curiosity and a spirit of discovery. Growing up with an electrical engineer and English curiosity teacher for parents, talk around the dinner table often revolved around science, education or both. My parents Canada’s 2019 always encouraged me to ask questions – nurturing an winners of inquisitiveness that would drive my scientifc career. I international awards wish everyone had that opportunity and encouragement. Creativity and innovation thrive when people are encouraged to ask questions for their own sake. The value of this approach to life, and research, is exemplifed by the 2019 international research award winners and is something I’ve experienced throughout my own career. My early research was fuelled by my fascination with the relationship between light and matter. I could never have imagined that it would lead to industrial and medical applications for lasers, let alone the Nobel Prize in Physics. Encouraging curiosity and science literacy is crucial to building a brighter future and equipping Canada’s next generation of researchers and innovators to tackle challenges and harness opportunities we have yet to even imagine. When we make science and research across disciplines more accessible, we open minds to the wonders of our world and increase evidence-based discussion and Foreword by Dr. -

Feldbusch Wiesner at the Interstice Of

AT THE INTERSTICE OF JESSICA EATON (*1977, Regina, Canada) creates stunning images of bright cubes and geo- CHRISTIANE FESER (*1977, Würzburg, Germany) works at the interstice of photogra- LAURIE KANG (*1985, Toronto, Canada) transcends the boundary between image and ob- metric structures with formal associations to colour field paintings by Bridget Riley, Josef Albers phy and object. The presented series Latente Konstrukte consists of repetitive, polydimensional ject. In a skilfully staged coalescence of photography, collage, sculpture and installation, she e FELDBUSCH PHOTOGRAPHY AND SCULPTURE and Sol LeWitt. At first glance, the viewer is ignorant of their elaborate production: the forms geometric structures. The detailed and clear-cut constructions require up to five steps to fabri- ploys the integral material of contemporary photo production as her primary artistic resource: emerge inside the camera in an additive colour process she discovered in an ancient Kodak cate: the artist builds paper models and photographs these, sculpts and folds the photographs, the C-print. She preferably uses Kodak Endura glossy chromogenic paper to create objects and WIESNER CUT FOLD REWRITE manual. and photographs the structures again. The elaborate method of production is not immediately montages. Thus, the material carrier of photography becomes an independent artistic element. AT THE INTERSTICE OF obvious in the multi-layered results, which share formal qualities with works by El Lissitzky and The paper of her Untitled Forms sculptures is unprocessed and continues to be light sensitive, In a modern world where digital photography and smartphones allow for instant Mondrian. They evoke architectonic spaces, play with light, shadow – and the viewer’s sense resulting in delicate shades of pastel. -

Jessica Eaton: New Works May 1 – 31, 2014

Jessica Eaton: New Works May 1 – 31, 2014 Opening reception Thursday, 1 May, 6:30-8:30pm Jessica Bradley Gallery is pleased to present celebrated Canadian photographer Jessica Eaton’s first solo exhibition with the gallery. A photography graduate from Vancouver’s Emily Carr University who now resides in Montreal, Eaton has quickly risen to international prominence. Her work was recently lauded in The Guardian as “a dramatically beautiful response to the ongoing debate about photography's meaning in our age of relentless digital distraction.” Jessica Eaton uses analogue techniques often dating from the early years of photography to explore the elemental properties of the medium. She is renowned for her richly hued geometric compositions, which she describes as “photographs I wasn’t able to see before they existed.” Though her works are often mistaken for digital manipulations, her colour palette is produced entirely within the camera using filters and multiple exposures. While these optical effects appear to be entirely abstract, they result from an elaborate process of transforming her subjects into pure evocations of light. Interested in how a camera and the light sensitive matter of film can be used to “see” beyond what is possible within human vision, Eaton has taken her experimentation with colour and light to new levels of intensity and complexity in her most recent works. Jessica Eaton has had solo exhibitions at The Photographers’ Gallery, The Hospital Club, London (2014); Hyères International Festival of Fashion and Photography, France (2013); California Museum of Photography, Riverside (2013); M+B Gallery, Los Angeles (2012), Higher Pictures, New York (2011), and Red Bull 381 Projects, Toronto (2011). -

Jessica Eaton, Iterations

NEWS RELEASE Exhibition: Jessica Eaton, Iterations (III) Dates: October 19 - November 30, 2019 Opening: Saturday, October 19, 2019 from 4-6pm Higher Pictures presents Iterations (III), featuring new work by Jessica Eaton. This is Eaton’s fourth solo exhibition with the gallery. Developed over three years of intensive experimentation in the studio, Iterations is Eaton’s most ambitious and technically complex body of work to date. It builds on a previous series in which Eaton constructed the colors in her final photographs through a laborious, analogue process, repositioning photography as a correlative of perception rather than of sight. In Iterations Eaton pushes this line of inquiry further, using a system entirely of her own creation—one that harnesses the additive color process in conjunction with the zone system—to test the limits of film’s potential. Eaton makes each photograph by layering dozens of individual exposures onto a sheet of 4 x 5 film—a precise registration process that she completes in the dark, blindly, before building the final image. What appear in the photographs are nested arrangements of three-dimensional geometric objects that are painted in a range of tonal grays. Eaton methodically adds, removes, substitutes, and moves pieces in between each exposure. The vibrant colors in the final prints are made using a mathematical equation—developed by Eaton from her earlier experiments—that guides her use of RGB color filters to carefully build up the desired hues in-camera. Each photograph compresses a series of actions and interventions made over time (combining the studio and the darkroom) into a single image that cannot be replicated in physical space. -

2019 Annual Report Contents

2019 Annual Report Contents 2 Board Chair’s Message 3 Executive Director & CEO message 6 Curatorial 26 Learning & Engagement 30 Development 34 Support 36 Financial Statements “Amalie Atkins is an outstanding artist working in film. It is such an honour as a curator to have the trust of artists to bring major work to museum audiences. Atkins had been working on this three-part, 16 mm film project for about ten years and it was amazing to have so many of Remai Modern is all lit up at LUGO in January. Photo: Carey Shaw. the contributors come to the live screening and launch.” – Sandra Fraser, Curator (Collections) We are grateful for support from: This Page: Installation view, Amalie Atkins, The Diamond Eye Assembly, Remai Modern, Saskatoon, 2019. Photo: Blaine Campbell. Cover: Nic Lehoux. 2 Board Chair’s Message Executive Director & CEO Message In 2019, Remai Modern delivered a year of engaging I am grateful to all the museum’s staff who worked exhibitions, programs and activities. The museum tirelessly to deliver outstanding work. continued to build on its vision to be a thought leader and direction-setting art museum that boldly Likewise, I am grateful to the Remai Modern Board collects, develops, presents and interprets the art Directors and Remai Modern Foundation Board of our time. Directors, especially Beau Atkins, Board Chair, and Herb McFaull, Foundation Board Chair, for their trust As a young arts institution situated in the Prairies, and guidance. the possibilities for Remai Modern’s contribution to this region are endless. I joined Remai Modern I am further grateful for the many artists, volunteers, as Interim Executive Director & CEO in April 2019. -

Living in Colour Canadian Chroma

ART CANADA INSTITUTE INSTITUT DE L’ART CANADIEN LIVING IN COLOUR CANADIAN CHROMA Beat the winter blues with these bright works. Here are twelve artists drawn to sumptuous hues and the splendour of colour. Greg Curnoe, Large Colour Wheel, 1980 This week the Art Canada Institute is taking a cue from Michael Gibson and his eponymous London, Ontario, gallery where the brilliant show Chroma is currently on view (and equally fantastic in its online format). The exhibition named for the Greek word for colour offers a break from the monochromatic monotony of February to bring much- needed colour into our lives. Moved by Gibson’s uplifting concept we are offering our own take on exploring colour by featuring Canadian art that unabashedly celebrates its visual and emotional power. From William Perehudoff’s lyrical colour field paintings to Gathie Falk’s surreal monochromatic sculptures to Robert Davidson’s geometric abstractions that draw on traditional Haida knowledge, these works demonstrate the elemental nature of radiant shades and their startling power to evoke emotion, excitement, and joy. Sara Angel Founder and Executive Director, Art Canada Institute PLASTIC BOUQUET by Sarah Anne Johnson Winnipeg artist Sarah Anne Johnson’s (b.1976) close-up shot of hands delicately holding purple orchids against a background of wild plants evokes welcome thoughts of spring and new growth. Yet, as the work’s title indicates, the flowers are artificial—Johnson has glued them onto the surface of the photograph. Plastic Bouquet, 2018, prompts us to question our relationship to nature and photography, and to examine our contradictory desires for both photographic authenticity and idealized representations of nature. -

Jessica Eaton

JESSICA EATON Press Pack 612 NORTH ALMONT DRIVE, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 TEL 310 550 0050 FAX 310 550 0605 WWW.MBART.COM JESSICA EATON BORN 1977, Regina, Saskatchewan EDUCATION 2006 BFA Photography, Emily Carr University of Art and Design, Vancouver SOLO & TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2016 M+B, Los Angeles, CA Transmutations, Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran, Montreal, QC 2015 Wild Permutations, Oakville Galleries at Centennial Square, Oakville, ON Custom Colour, Higher Pictures, New York, NY Wild Permutations, MOCA Cleveland, Cleveland, OH 2014 Jessica Eaton: New Works, Jessica Bradley Gallery, Toronto, ON Ad Infinitum, The Photographers’ Gallery/The Hospital Club, London, UK 2013 Flash: Jessica Eaton, California Museum of Photography, Riverside, CA Hyères 2013: International Festival of Fashion and Photography, Hyères, France 2012 Polytopes, M+B, Los Angeles, CA Squeezed Coherent States, Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto, ON 2011 Cubes for Albers and LeWitt, Higher Pictures, New York, NY The Whole is Greater Than The Sum of The Parts: Lucas Blalock and Jessica Eaton, Contact Gallery / Contact Photography Festival 2011, Toronto, ON 2010 Strata: New works by Jessica Eaton, Red Bull 381 Projects, Toronto, ON Umbra Penumbra, PUSH Galerie, Montréal, QC 2009 Variables, LES Gallery, Vancouver Photographs, Hunter and Cook HQ, Toronto, ON GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2016 There is nothing I could say that I haven’t thought before, in collaboration with Cynthia Daignault, Stems Gallery, Brussels, Belgium 2015 Russian Doll, M+B, Los Angeles, CA Are You Experienced?, -

Newsletter Photography Pioneers

ART CANADA INSTITUTE INSTITUT DE L’ART CANADIEN AUGUST 20, 2021 PHOTOGRAPHY PIONEERS TWELVE CANADIAN ARTISTS In honour of this week’s World Photography Day, we’re looking at some of this country’s innovators who have helped define the medium since its mid-nineteenth-century creation. Many of Canada’s best-known artists are photographers. Yet it wasn’t until the 1960s—over a century after the medium’s birth in 1839—that most public institutions saw it as a genre worthy of a department of its own. That decade marked a pivotal period in the growth of photography when the camera became an important tool to respond to emerging social movements, as well as questions of identity, the self, and community. Yesterday (August 19) marked World Photography Day and a celebration of the art, science, and craft of the camera. At the Art Canada Institute, the dramatic impact of photography will be explored in our forthcoming 2023 publication Photography in Canada: The First 150 Years, 1839–1989 by Dr. Sarah Bassnett and Dr. Sarah Parsons. In the meantime, here’s a selection of photographic masterpieces by creators who pushed the medium— and Canadian art—in new and important directions. Sara Angel Founder and Executive Director, Art Canada Institute AROUND THE CAMP FIRE by William Notman William Notman, Around the Camp Fire, Caribou Hunting series, Montreal, 1866, McCord Museum, Montreal. Scottish-born, Montreal-based William Notman (1826– 1891) was the first Canadian photographer to achieve an international reputation. Long before the technology of Photoshop, he was famous for his elaborate composite pictures and meticulously staged outdoor scenes—such as Around the Camp Fire, 1866—that were created inside his studio. -

Jessica Eaton

JESSICA EATON BORN 1977, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada Lives and works in Montréal, Canada EDUCATION 2006 BFA Photography, Emily Carr University of Art and Design, Vancouver, Canada SOLO & TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2019 Iterations (II), M+B Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2018 Iterations (I), Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran, Montreal, Canada 2017 Pictures for Women, Higher Pictures, New York, NY 2016 M+B Gallery, Los Angeles, CA Transmutations, Galerie Antoine Ertaskiran, Montreal, Canada 2015 Wild Permutations, Oakville Galleries at Centennial Square, Oakville, ON Custom Colour, Higher Pictures, New York, NY Wild Permutations, MOCA Cleveland, Cleveland, OH 2014 Jessica Eaton: New Works, Jessica Bradley Gallery, Toronto, ON Ad Infinitum, The Photographers’ Gallery/The Hospital Club, London, UK 2013 Flash: Jessica Eaton, California Museum of Photography, Riverside, CA Hyères 2013: International Festival of Fashion and Photography, Hyères, France 2012 Polytopes, M+B, Los Angeles, CA Squeezed Coherent States, Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto, ON 2011 Cubes for Albers and LeWitt, Higher Pictures, New York, NY The Whole is Greater Than The Sum of The Parts: Lucas Blalock and Jessica Eaton, Contact Gallery / Contact Photography Festival 2011, Toronto, ON 2010 Strata: New works by Jessica Eaton, Red Bull 381 Projects, Toronto, ON Umbra Penumbra, PUSH Galerie, Montréal, QC 2009 Variables, LES Gallery, Vancouver Photographs, Hunter and Cook HQ, Toronto, ON 612 NORTH ALMONT DRIVE, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 TEL 310 550 0050 FAX 310 550 0605 WWW.MBART.COM GROUP -

Wild Permutations February 6–May 24, 2015

JESSICA EATON WILD PERMUTATIONS FEBRUARY 6–MAY 24, 2015 11400 Euclid Avenue Cleveland, Ohio 44106 216.421.8671 | www.MOCAcleveland.org ©2015 Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland JESSICA EATON WILD PERMUTATIONS February 6–May 24, 2015 Mueller Family Gallery Organized by Rose Bouthillier, Associate Curator Jessica Eaton (1977, Regina, Canada) lives and works in Montreal, Canada. Solo exhibitions of her work have been held at CONTACT Photography Festival, Toronto, and The Photographers’ Gallery, London. She has been featured in numerous group exhibitions, including New Positions in American Photography (2014), Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam; Phantasmagoria (2012), Presentation House Gallery, Vancouver; Photography is Magic (2012), Daegu Photography Biennale, South Korea; Québec Triennial (2011), Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. Eaton is the recipient of The Magenta Foundation’s Bright Spark Award (2011) and the Photography Jury Grand Prize at the International Festival of Fashion and Photography, Hyères, France (2012). In 2013 she was long listed for the AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize. SPONSORS MOCA Cleveland’s presentation of Wild Permutations is made possible by the generous support of: Paul E. Bain The Fred and Laura Ruth Bidwell Foundation The Elizabeth Firestone Graham Foundation With additional support from: Anselm Talalay Photography Endowment All 2015 exhibitions are funded by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and Leadership Circle gifts from the Britton Fund, Doreen and Dick Cahoon, Victoria Colligan and John Stalcup, Lauren Rich Fine and Gary Giller, Joanne Cohen and Morris Wheeler, Margaret Cohen and Kevin Rahilly, Becky Dunn, Barbara and Peter Galvin, Harriet and Victor Goldberg, Agnes Gund, Donna and Stewart Kohl, Toby Devan Lewis, Marian and Boake Sells, and Scott Mueller.