Cognition and Motor Execution in Piano Sight-Reading: a Review of Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Dictionary of Music and Musicians

The New GROVE Dictionary of Music and Musicians EDITED BY Stanley Sadie 12 Meares - M utis London, 1980 376 Moda Harold Powers Mode (from Lat. modus: 'measure', 'standard'; 'manner', 'way'). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term 'mode' has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and in this century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain pheno mena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see SOUND, §5. I. The term. II. Medieval modal theory. III. Modal theo ries and polyphonic music. IV. Modal scales and folk song melodies. V. Mode as a musicological concept. I. The term I. Mensural notation. 2. Interval. 3. Scale or melody type. I. MENSURAL NOTATION. In this context the term 'mode' has two applications. First, it refers in general to the proportional durational relationship between brevis and /onga: the modus is perfectus (sometimes major) when the relationship is 3: l, imperfectus (sometimes minor) when it is 2 : I. (The attributives major and minor are more properly used with modus to distinguish the rela tion of /onga to maxima from the relation of brevis to longa, respectively.) In the earliest stages of mensural notation, the so called Franconian notation, 'modus' designated one of five to seven fixed arrangements of longs and breves in particular rhythms, called by scholars rhythmic modes. -

Improvisation: an Integral Step in Piano Pedagogy Lauren French Trinity University

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Music Honors Theses Music Department 5-17-2005 Improvisation: An Integral Step in Piano Pedagogy Lauren French Trinity University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/music_honors Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation French, Lauren, "Improvisation: An Integral Step in Piano Pedagogy" (2005). Music Honors Theses. 1. http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/music_honors/1 This Thesis open access is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Improvisation: An Integral Step In Piano Pedagogy by Lauren Ann French A department honors thesis submitted to the Department of Music at Trinity University in partial fulfillments of the requirements for graduation with departmental honors 20 April 2005 ____________________________ _____________________________ Thesis Advisor Department Chair Associate Vice-President for Academic Affairs, Curriculum and Student Issues This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/> or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgments Improvisation Contextualized Improvisation vs. Composition Improvisation in Keyboard Pedagogy Teaching Philosophy of Robert Pace Improvisation in Current Piano Method Books Keyboard Reading Approaches Method Book Review Frances Clark and the Music Tree Faber and Piano Adventures The Hal Leonard Student Piano Library Robert Pace and Musicfor Piano Application of Improvisation in Advanced Repertoire Mozart's Piano Sonata K. -

Teaching Music with Keyboard Improvisation: a Pedagogical Journey Involving Four Older Adults

Teaching Music with Keyboard Improvisation: A Pedagogical Journey Involving Four Older Adults by Lisa Tahara A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Lisa Tahara 2015 Teaching Music with Keyboard Improvisation: A Pedagogical Journey Involving Four Older Adults Lisa Tahara Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto 2015 Abstract The life expectancy of individuals has risen in the twentieth-century, due largely to improvements in health, technology, and nutrition. Accordingly, the older adult population has been increasing rapidly and, as a result, there is a need for greater attention and emphasis to be placed on their wellbeing. Research has shown that the older adult population is interested in music learning programs where they may be given the opportunity to actively create music in group settings. However, music programs have traditionally been based on notation and reading, and this approach may not be optimal for a student entering a music learning program later in life. This research study began as an exploration of how music instruction with improvisation may impact the wellbeing, enjoyment, and confidence levels of older adults. Four older adults between the ages of 83 and 90 participated in a music learning program involving a basic curriculum and improvisation over a period of three months. Qualitative data was collected in the form of audiovisual materials, individual interviews, and through focus group sessions. Quantitative data was gathered using pre and post-test surveys to examine differences in quality of life, musical aptitude, and mood. -

"Fixed Do": What They Are, What They Aren't, and Why "Movable Do" Should Be Used As the Basis for Musicianship Training

"Movable do" and "fixed do": what they are, what they aren't, and why "movable do" should be used as the basis for musicianship training. PART I - SYSTEMATIC "Movable do" The "movable do" system is based on the understanding that the names given to the notes serve as reminders, to aid the singer in correctly establishing the distance between the various scale degrees. The syllables are: "do re mi fa sol la ti". In some common misrepresentations of this method, the seventh syllable is given as "si" instead of "ti". The latter is obviously a better choice, since it does not reuse the consonant "s". In the major-minor key system, central to the language of European art- music from 1700 to 1900, and still thriving in certain streams of popular music, chromatic alteration of the "natural" scale degrees comes about mainly because of modulation, in which the tonic note shifts to a new pitch, or else because of scale coloration, in which the new notes are used simply to vary the character of the prevailing scale without suggesting a change of tonic. The boundary between these two procedures is not always clear, but the "movable do" system addresses that line, however fine, in a way that leaves the perceptual and analytical processes open to productive discussion. When chromaticism is locally based, that is, without modulation, the solmization syllables are: ascending: do di re ri mi fa fi sol si la li ti do descending: do ti ta la le sol fi fa mi ma re ra do When modulation is involved, the system tends to grow progressively more flexible in its application and, as the harmonic style itself, more complex. -

A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners

A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners Pai-Yu Chiu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctoral of Music and Arts University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Craig Sheppard, Chair Donna Shin Steven J. Morrison Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2017 Pai-Yu Chiu ii University of Washington Abstract A Comparative Evaluation of Group and Private Piano Instruction on the Musical Achievements of Young Beginners Pai-Yu Chiu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Craig Sheppard School of Music This study compares the relative influence of group and individual piano instruction on the musical achievements of young beginning piano students between the ages of 5 to 7. It also investigates the potential influence on these achievements of an individual teacher’s preference for either mode of instruction, children’s age and gender, and identifies relationships between these three factors and the two different modes of instruction. Forty-five children between the ages of 5 to 7 without previous musical training completed this empirical study, which consisted of 24 weekly piano instruction and a posttest evaluating their musical achievements. The 45 participants included 25 boys and 20 girls. The participants were comprised of twenty-seven 5- year-olds, nine 6-year-olds, and nine 7-year-old participants. Twenty-two children participated in group piano instruction and 23 received private instruction. After finishing 24 weekly lessons, participants underwent a posttest evaluating: (1) music knowledge, (2) music reading, (3) aural iii discrimination, (4) kinesthetic response, and (5) performance skill. -

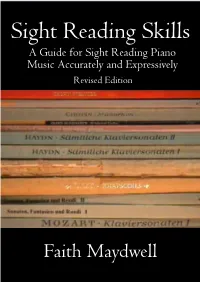

A Guide for Sight Reading Piano Music Accurately and Expressively Nerevised Edition

Sight Reading Skills A Guide for Sight Reading Piano Music Accurately and Expressively NeRevised Edition Faith Maydwell West Australian-born Faith Maydwell has taught piano for more than 30 years. Her complementary activities since completing a Master of Music degree at the University of Western Australia in 1982 have included solo recitals, broadcasts for the Australian Broadcasting Commission, accompanying, orchestral piano with the West Australian Symphony Orchestra, examining for the Australian Music Examinations Board, lecturing at the University of Western Australia and the West Australian Academy of Performing Arts in the areas of keyboard harmony, sight reading and piano pedagogy, adjudicating, and presenting papers at state and national music seminars and conferences. Faith’s university piano studies were under the tutelage of David Bollard (a student of Ilona Kabos and Louis Kentner), a founding member of the Australia Ensemble. In 1978 Faith won the Convocation Prize (UWA) for the best student of any year in the Bachelor of Music course and in 1979 she was a state finalist in the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s Young Performers Awards competition. She has published a book, Piano Teaching: A Guide for Nurturing Musical Indepen- dence (See inside back cover for details). Sight Reading Skills A G uide for Sight Reading Piano Music Accurately and Expressively Revised Edition Faith Maydwell THE NEW ARTS PRESS OF PERTH AUSTRALIA New Arts Press of Perth 31B Venn Street North Perth 6006 Western Australia Copyright © 2007 by Faith Maydwell All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. The New Arts Press of Perth and colophon are trademarks of The New Arts Press of Perth, Inc. -

11.2020-Hawaiʻi-MTNA-Competition

Hawaiʻi MTNA Competition Junior Piano CONTESTANTS: Sola Bando, Justin Chan, Sophie Chan, Jannik Evanoff, Isabella Liu, Anderson Mao, Aya Okimoto TEACHERS: Steven Casano, Monica Chung, Joyce Shih, Annu Shionoya, Wendy Yamashita, Thomas Yee Contestant #1 Piano Sonata No. 16 in C Major, K. 545 W.A. Mozart I. Allegro Waltz in D-flat Major, Op. 64, No. 1 Frédéric Chopin Contestant #2 Sonata in B minor No. 47, Hob. XVI/32 Franz Joseph Haydn I. Allegro moderato The Lark Glinka arr. Bakakirev If I Were a Bird (Si Oiseau J'etais), Op. 2, No. 6 George Martin Adolf von Henselt Six Romanian Folk Dances, Sz. 56 Béla Bartók Contestant #3 Italian Concerto in F Major, BWV 971 Johann Sebastian Bach I. Allegro Nocturne in C-sharp Minor, Op. posth. Frédéric Chopin Three Preludes George Gershwin III. Allegro ben ritmato e deciso Sonata in C-sharp Minor, Op. 27, No. 2 Ludwig van Beethoven III. Presto agitato Contestant #4 Sonata in F Minor, Op. 2, No. 1 Ludwig van Beethoven I. Allegro II. Adagio Seven Morceaux de Salon, Op. 10 Sergei Rachmaninoff II. Valse III. Barcarolle Contestant #5 Italian Concerto in F Major, BWV 971 Johann Sebastian Bach III. Presto Milonga, Op. 3 Alberto Ginastera Impromptu No. 1 in A-flat major, Op. 29 Frédéric Chopin Contestant #6 Rondo a Capriccio, Op. 129 Ludwig van Beethoven Impromptu in G-flat major, Op. 90, No. 3 Franz Schubert Wedding Day at Troldhaugen, Op. 65, No. 6 Edvard Grieg Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm from ‘Mikrokosmos’ Béla Bartók No. 2 & 6, Sz. 107/6/149 and 153 Contestant #7 Scherzo No. -

Western Culture Has Roots in Ancient

3 13. What happened in 395, 476, 1054, 1453? Chapter 2 Division (Milan, Rome) and (Byzantium, Constantinople, The Christian Church in the First Millennium Istanbul); fall of Rome; Roman Catholic Church and Byzantine Church split; fall of Constantinople. East 1. (22) How is the history of music in medieval Europe under the control of the emperor; in the west a bishop intertwined with the history of the Christian church? assumed authority Notation and polyphony developed within church music; schools were church; composers and theorists were 14. (26) SR: What two things did singing of psalms trained there; notation preserved the music of the church accomplish for St. Basil? Taught doctrine; softens an angry spirit 2. (23) What was the deal about Christianity before 313? OK as long as worship Roman gods and emperors; Christians 15. SR: What was Augustine's dilemma and justification? had only one god and tried to convert others. Deeply moved but was also pleasurable; weaker souls would benefit more 3. What did the Edict of Milan do? Legalized Christianity and church own property 16. (27) SR: Who was Egeria? What texts were sung? Any ethos going on? What service was it? 4. What happened in 392? Spanish nun on pilgrimage to Jerusalem; psalms; people wept Christianity is the official religion; all others suppressed when gospel was read; Matins except Judaism 17. What is the language of the Catholic Church? 5. What's the connection between Christian observances Byzantine? TQ: Old Testament? New Testament? and Jewish traditions? Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Greek Chanting of Scripture and singing of psalms 18. -

Piano: Resources

Resources AN ADDENDUM TO THE PIANO SYLLABUS 2015 EDITION Resources The following texts are useful for reference, teaching, and examination preparation. No single text is necessarily complete for examination purposes, but these recommended reading and resource lists provide valuable information to support teaching at all levels. Resources for Examination Preparation Repertoire Additional Syllabi of Celebration Series®, 2015 Edition: Piano Repertoire. The Royal Conservatory (Available online.) 12 vols. (Preparatory A–Level 10) with recordings. Associate Diploma (ARCT) in Piano Pedagogy Toronto, ON: The Frederick Harris Music Co., Licentiate Diploma (LRCM) in Piano Performance Limited, 2015. Popular Selection List (published biennially) Theory Syllabus Etudes Celebration Series®, 2015 Edition: Piano Etudes. 10 vols. Official Examination Papers (Levels 1–10) with recordings. Toronto, ON: The Royal Conservatory® Official Examination Papers. The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited, 2015. 15 vols. Toronto, ON: The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited, published annually. Technical Tests The Royal Conservatory of Music Piano Technique Book, Basic Rudiments 2008 Edition: “The Red Scale Book.” Toronto, ON: The Intermediate Rudiments Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited. Advanced Rudiments Scales, Chords, and Arpeggios for Piano: “The Brown Scale Introductory Harmony Book.” Toronto, ON: The Frederick Harris Music Co., Basic Harmony Limited, 2002. First published 1948. Basic Keyboard Harmony Technical Requirements for Piano, 2015 Edition. 9 vols. History 1: An Overview (Preparatory A–Level 8). Toronto, ON: The Frederick Intermediate Harmony Harris Music Co., Limited, 2015. Intermediate Keyboard Harmony History 2: Middle Ages to Classical Musicianship (Ear Tests and Sight Counterpoint Advanced Harmony Reading) Advanced Keyboard Harmony Berlin, Boris, and Andrew Markow. Four Star® Sight History 3: 19th Century to Present Reading and Ear Tests, 2015 Edition. -

Sight-Reading Curriculum for Group Piano Class

Running head: SIGHT-READING CURRICULUM FOR GROUP PIANO CLASS SIGHT-READING CURRICULUM FOR GROUP PIANO CLASS: BEGINNER TO INTERMEDIATE LEVEL By STEPHEN DANIEL GEORGER SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: DR. SANDY B. GOLDIE, CHAIR DR. KEITH THOMPSON, MEMBER A PROJECT IN LIEU OF THESIS PRESENTED TO THE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2015 SIGHT-READING CURRICULUM FOR GROUP PIANO CLASS 2 Abstract The purpose of the project is to review what research has been done on sight-reading at the piano for beginner and intermediate level students and to create a curriculum to help students better their sight-reading skills with regards to melodic reading and rhythmic reading. Two questions have been addressed throughout my research. The first one is: what are the components of effective sight-reading skills (the ability to look ahead in the music, reading rhythms, understanding keyboard geography)? The second one is: what are the most appropriate teaching strategies and activities to include in an effective sight-reading curriculum for group piano class? This curriculum can be utilized for all beginner to intermediate level piano students at the secondary school or collegiate level. It is designed to incorporate principals of having the ability to look ahead in the music, the ability to recognize common pitch patterns (major chords, scales and arpeggios), the ability to recognize common rhythm patterns, the ability to predict what is coming next in the music and understanding keyboard geography. The curriculum accommodates a fifteen week course that meets two hours per week (two days per week, one hour per day). -

Utilizing Immediate Feedback in Piano Pedagogy Michael Szabo

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 3-23-2016 Utilizing Immediate Feedback in Piano Pedagogy Michael Szabo Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Other Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Scholar Commons Citation Szabo, Michael, "Utilizing Immediate Feedback in Piano Pedagogy" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6147 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Utilizing Immediate Feedback in Piano Pedagogy by Michael Szabo A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Child and Family Studies College of Behavioral and Community Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kwang-Sun Blair, Ph. D., BCBA-D Timothy M. Weil, Ph. D., BCBA-D Kimberly Crosland, Ph. D., BCBA-D Date of Approval March 22, 2016 Keywords: Tactile feedback, skill acquisition, behavior analysis, music education Copyright © 2016, Michael Szabo DEDICATION I dedicate this manuscript to my parents, Bob and Laura Szabo, for their constant support throughout my life. Their encouragement of my musical endeavors and education have been invaluable. I also dedicate this to my brothers at the Epsilon Iota chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia for the values they instilled in me and their dedication to advancing music in America. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge my entire thesis committee who have supported me throughout my education and this project. -

Annotated Bibliography of Sources on the History of Piano Pedagogy Compiled by Members of the NCKP Historical Perspectives Committee

Annotated Bibliography of Sources on the History of Piano Pedagogy Compiled by Members of the NCKP Historical Perspectives Committee Connie Arrau Sturm (CAS) – Committee Chairman Debra Brubaker Burns (DBB) Anita Jackson (AJ) General historical surveys Boardman, Roger Crager. “A History of Theories of Teaching Piano Technic.” Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1954. Boardman investigated how theories of teaching piano technique changed from 1753 to 1953. He classified the theories into three categories - finger technique, use of the arm, and weight/relaxation. Within each category of theories, he not only analyzed how the body was used and how it interacted with the instrument, but also discussed how these techniques were taught. Boardman’s comparisons among theories helped pinpoint when important changes occurred, revealing the special contributions of each pedagogue. Boardman concluded that concepts of piano technique evolved from use of fingers only, to the coordination of the entire body (highlighting the importance of the brain). He also noted the strong influence of environmental factors (e.g., changes in the instrument, changes in the repertoire, and inspiration of great performers of the day) on the development of theories of teaching piano technique. (CAS) Bomberger, E. Douglas, Martha Dennis Burns, James Parakilas, Judith Tick, Marina Tsvetaeva, and Mark Tucker. “The Piano Lesson” In Piano Roles: Three Hundred Years of Life with the Piano. James Parakilas, 133-179. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1999. This chapter chronicled how teaching piano and studying piano have changed over the centuries. The authors described the evolution of piano study from eighteenth-century daily lessons, where students practiced in the presence of the piano teacher, to nineteenth-century weekly lessons that required long hours of daily practice in between.