Literature Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Muslimah Sex Manual: a Halal Guide to Mind Blowing

The Muslimah Sex Manual A Halal Guide to Mind Blowing Sex Contents: Acknowledgements Ready Introduction Who this for? Myth Anatomy Body Image Genital hygiene Birth control Lube Kegels Sexting Dirty talk Flirting with other men First time Kissing Handjobs How to give a blowjob Massage Stripping Positions What to say during sex How to be a freak in bed Dressing up Dry humping Breast sex Femoral sex Quickie Shower sex Rough sex Forced sex BDSM Public sex Anal play Threesome Simple things Acknowledgements This book could not have been written without the encouragement of those around me. I would like to thank Zainab bint Younus who blogs at The Salafi Feminist for reading and reviewing a manuscript of this book. I would also like to thank Nabeel Azeez who blogs at Becoming the Alpha Muslim for his help in marketing this book. There are several other people whose help was invaluable but would prefer to stay anonymous. They have my heartfelt thanks and appreciation. Ready? I’ll take you down this delightful rabbit hole of pleasure. Let me warn you, this is not for the faint of heart. I’m going to talk about things that you would never bring up in conversation. I will teach you how to make your husband look at you with unbridled lust. You will find your husband transformed into a man who can’t keep his hands off of you and brims with jealousy when other men so much as glance at you. If you’re unprepared for that, put this book away. If not, let’s begin. -

4. UK Films for Sale at EFM 2019

13 Graves TEvolutionary Films Cast: Kevin Leslie, Morgan James, Jacob Anderton, Terri Dwyer, Diane Shorthouse +44 7957 306 990 Michael McKell [email protected] Genre: Horror Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Director: John Langridge Home Office tel: +44 20 8215 3340 Status: Completed Synopsis: On the orders of their boss, two seasoned contract killers are marching their latest victim to the ‘mob graveyard’ they have used for several years. When he escapes leaving them no choice but to hunt him through the surrounding forest, they are soon hopelessly lost. As night falls and the shadows begin to lengthen, they uncover a dark and terrifying truth about the vast, sprawling woodland – and the hunters become the hunted as they find themselves stalked by an ancient supernatural force. 2:Hrs TReason8 Films Cast: Harry Jarvis, Ella-Rae Smith, Alhaji Fofana, Keith Allen Anna Krupnova Genre: Fantasy [email protected] Director: D James Newton Market Office: UK Film Centre Gropius 36 Status: Completed Home Office tel: +44 7914 621 232 Synopsis: When Tim, a 15yr old budding graffiti artist, and his two best friends Vic and Alf, bunk off from a school trip at the Natural History Museum, they stumble into a Press Conference being held by Lena Eidelhorn, a mad Scientist who is unveiling her latest invention, The Vitalitron. The Vitalitron is capable of predicting the time of death of any living creature and when Tim sneaks inside, he discovers he only has two hours left to live. Chased across London by tabloid journalists Tooley and Graves, Tim and his friends agree on a bucket list that will cram a lifetime into the next two hours. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Language Syllabus

Language Syllabus Level 4 Target Vocabulary Target Structures Level 4 Target Vocabulary Target Structures Review of Beep! 3 vocabulary Review of Beep! 3 structures Food: burger, cereal, egg, ham, meat, How much is the soup? Welcome 5 Let’s eat! rice, salad, soup, toast, vegetables It’s four euros, fifty cents. back! Meals: breakfast, dinner, lunch I have cereal for breakfast. School subjects: Art, English, IT, On Monday, I´ve got/haven’t got 1 Time for Maths, Music, PE, Science, Spanish Maths. Can I have a sandwich, please? school! Days of the week: Monday, Tuesday, What have you got on Friday? Phonics Tongue Twister: a Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday Phonics Tongue Twister: i, y Animals: ant, bee, centipede, They’ve got/They haven’t got wings. 6 Minibeasts dragonfly, grasshopper, ladybird, snail, Countries: China, France, Ireland, Where are you from? worm; carnivore, herbivore, omnivore How many legs have they got? 2 Where are Italy, Mexico, Spain, the UK, the USA I’m from France. you from? Body parts: antennae, legs, stings, Phonics Tongue Twister: o Nationalities: Arabic, Chinese, He’s/She’s from Italy. wings English, French, Italian, Spanish I speak Chinese. Nature: flower, grass, leaf, pond, tree He/She likes cycling. Review 2 Units 4, 5, 6 Phonics Tongue Twister: a Months: January, February, March, What do you wear? Space: comet, moon, planet, satellite, Does he/she work on a space 3 Months April, May, June, July, August, I wear/don’t wear a jumper. 7 Space spaceship, stars, telescope, UFO station? September, October, November, December In (January, winter)… The Planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, He listens/doesn’t listen to music. -

Selena Gomez Show Date: Weekend of June 4-5, 2011 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: Subway Seg

Show Code: #11-23 Guest Host: Selena Gomez Show Date: Weekend of June 4-5, 2011 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: Subway Seg. 1 Content: #40 “LOOK AT ME NOW” – Chris Brown f/Lil Wayne & Busta Rhymes #39 “FIREWORK” – Katy Perry #38 “BOYFRIEND” – Big Time Rush f/New Boyz Commercials: :30 ABC Family/Swit :60 Proactiv :30 Subway/Fresh Bu Outcue: “...Subway eat fresh.” Segment Time: 15:16 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 2 Content: #37 “SING” – My Chemical Romance #36 “RAISE YOUR GLASS” – Pink #35 “THE STORY OF US” – Taylor Swift #34 “COMING HOME” – Diddy-Dirty Money f/Skylar Grey Commercials: :30 Stubhub.com :30 Devry Universit :30 Biore :30 Allegra Outcue: “...use as directed.” Segment Time: 19:48 Local Break 2:00 Seg. 3 Content: #33 “DYNAMITE” – Taio Cruz #32 “HELLO” – Martin Solveig & Dragonette #31 “PARTY ROCK ANTHEM” – LMFAO f/Lauren Bennett & Goon Rock Extra: “SAY HELLO TO GOODBYE” – Shontelle Commercials: :60 Proactiv Outcue: “...1-800-620-4040.” Segment Time: 17:41 Local Break 1:00 Seg. 4 ***This is an optional cut - Stations can opt to drop song for local inventory*** Content: AT40 Extra: “STOP AND STARE” – OneRepublic Outcue: “…Thanks, Kayla.” (sfx) Segment Time: 3:56 Hour 1 Total Time: 61:41 END OF DISC ONE Show Code: #11-23 Show Date: Weekend of June 4-5, 2011 Disc Two/Hour Two Opening Billboard Subway Seg. 1 Content: #30 “WHAT THE HELL” – Avril Lavigne #29 “GRENADE” – Bruno Mars #28 “GOOD LIFE” – OneRepublic Commercials: :30 Subway/Fresh Bu :30 Biore :60 Sensa Outcue: “...1-800-705-6559.” Segment Time: 14:45 Local Break 2:00 Seg. -

![From the Baffler No. 23, 2013]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6936/from-the-baffler-no-23-2013-326936.webp)

From the Baffler No. 23, 2013]

Facebook Feminism, Like It or Not SUSAN FALUDI [from The Baffler No. 23, 2013] The congregation swooned as she bounded on stage, the prophet sealskin sleek in her black skinny ankle pants and black ballet flats, a lavalier microphone clipped to the V-neck of her black button-down sweater. ―All right!! Let‘s go!!‖ she exclaimed, throwing out her arms and pacing the platform before inspirational graphics of glossy young businesswomen in managerial action poses. ―Super excited to have all of you here!!‖ ―Whoo!!‖ the young women in the audience replied. The camera, which was livestreaming the event in the Menlo Park, California, auditorium to college campuses worldwide, panned the rows of well-heeled Stanford University econ majors and MBA candidates. Some clutched copies of the day‘s hymnal: the speaker‘s new book, which promised to dismantle ―internal obstacles‖ preventing them from ―acquiring power.‖ The atmosphere was TED-Talk-cum-tent-revival-cum- Mary-Kay-cosmetics-convention. The salvation these adherents sought on this April day in 2013 was admittance to the pearly gates of the corporate corner office. ―Stand up,‖ the prophet instructed, ―if you‘ve ever said out loud, to another human being—and you have to have said it out loud—‗I am going to be the number one person in my field. I will be the CEO of a major company. I will be governor. I will be the number one person in my field.‘‖ A small, although not inconsiderable, percentage of the young women rose to their feet. The speaker consoled those still seated; she, too, had once been one of them. -

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

MNL and PMA Recommend That All Municipal Offices and Public Facilities Should Now Be Closed to the Public Including Appointments

Updated: May 1, 2020 1. WHAT ARE THE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MUNICIPAL OPERATIONS AND STAFFING? MNL and PMA recommend that all municipal offices and public facilities should now be closed to the public including appointments. Business continuity planning in the case of an emergency, if available, should now be in place. All municipalities should explore and encourage banking online or through the phone, or payments through cheque/money order if online banking is not a possibility. Where and when possible, office staff should be working from home. If staff cannot work from home, advised social distancing guidelines and hygiene practices should be maintained in the office. Public works and outside staff should follow social distancing and hygiene practices and should work from home on an on-call basis, when possible. Update May 1, 2020: MNL is seeking further clarification on the role of municipalities in reopening and what reopening means for municipal operations. 2. WE ARE A SMALL COMMUNITY WITH A SMALL MAINTENANCE STAFF. IF OUR STAFF BECOME ILL, WHAT SHOULD WE DO? Ensure anyone who is feeling ill calls 811 and self-isolates for their protection and the protection of others. Reach out to neighbouring communities now to discuss whether there is an opportunity to share staff across the region should the need arise – particularly for critical services like drinking water. Mutual aid agreements can be helpful in these situations. If all or a large portion of your staff fall ill, you will have to curtail services unless you are able to work out an arrangement with neighbouring municipalities. If you are unable to find another solution, contact the Department of Municipal Affairs and Environment. -

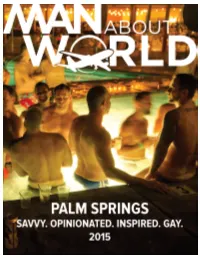

Manaboutworld PALM SPRINGS 2015.Pdf

Palm Springs: The ManAboutWorld Insiders Guide Palm Springs’ heyday may have begun with the early movie stars of TV, but the town’s gay renaissance began in the 1980s, when gay Angelenos started buying the mid-century modern homes in a then seedy and run downtown. Today, Palm Springs is a stylish and popular weekend getaway in season, from September through May, and never more glorious than it is right now. When LA is a “chilly” 68-70° in the winter and spring, Angelenos head to sunny Palm Springs for warm swimming pool weather. Despite its reputation as a major gay destination, at times it seems like there’s not much there, there — because there isn’t. Palm Springs is still a relatively small city, with a population of under 50,000 residents. The few gay bars and clubs it has are often deserted mid-week, even in season, and when the temperature soars in the summer, the town really slows down. But that slow pace is at the heart of Palm Springs’ appeal. This is a place to go when you want to do little more than relax by the pool, under a stunning vista of mountains and desert. There’s also tennis and golf, and just enough other active, cultural and shopping distractions for those who can’t sit still, and a large concentration of mid-century modern design, making it a world capital for those who share that fetish. For gay visitors, Palm Springs offers the largest concentration of gay resorts in the world: 22 small hotels and guesthouses catering primarily or exclusively to gay men. -

Sorted by ARTIST * * * * Please Note That The

* * * * Sorted by ARTIST * * * * Please note that the artist could be listed by FIRST NAME, or preceded by 'THE' or 'A' Title Artist YEAR ----------------------------------------- ------------------------ ----- 7764 BURN BREAK CRASH 'ANYSA X SNAKEHIPS 2017 2410 VOICES CARRY 'TIL TUESDAY 1985 2802 GET READY 4 THIS 2 UNLIMITED 1995 9144 MOOD 24KGOLDN 2021 8180 WORRY ABOUT YOU 2AM CLUB 2010 2219 BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN 2001 6620 HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 DOORS DOWN 2003 1517 KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN 2000 5216 LET ME GO 3 DOORS DOWN 2005 0914 HOLD ON LOOSELY 38 SPECIAL 1981 8115 DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 2009 8214 MY FIRST KISS 3OH!3/ KE$HA 2010 7336 AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2014 8710 EASIER 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2019 7312 SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2014 8581 WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2018 8611 YOUNGBLOOD 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 2018 7413 IN DA CLUB 50 CENT 2004 8758 ALL MY FRIENDS ARE FAKE 58TE McRAE 2020 2805 TOOTSIE ROLL 69 BOYZ 1995 8776 SAY SO 71JA CAT 2020 7318 ALREADY HOME A GREAT BIG WORLD 2014 7117 THIS IS THE NEW YEAR A GREAT BIG WORLD 2013 3109 BACK AND FORTH AALIYAH 1994 4809 MORE THAN A WOMAN AALIYAH 2002 1410 TRY AGAIN AALIYAH 2000 7744 FOOL'S GOLD AARON CARTER 2016 2112 I MISS YOU AARON HALL 1994 2903 DANCING QUEEN ABBA 1977 6157 THE LOOK OF LOVE (PART ONE) ABC 1982 8542 ODYSSEY ACCIDENTALS 2017 8154 WHATAYA WANT FROM ME ADAM LAMBERT 2010 8274 ROLLING IN THE DEEP ADELE 2011 8369 SOMEONE LIKE YOU ADELE 2012 5964 BACK IN THE SADDLE AEROSMITH 1977 5961 DREAM ON AEROSMITH 1973 5417 JADED AEROSMITH 2001 5962 SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH 1975 5963 WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH 1976 8162 RELEASE ME AGNES 2010 9132 BANG! AJR 2020 6906 I WANNA LOVE YOU AKON FEAT SNOOP DOGG 2007 7810 LOCKED UP AKON feat STYLES P. -

Where Do You Get That Noise?

as I could not put all my stuff on the ball you can bet that Hill never would of ran to first base and Violet would of been a widow and probily a lot better off than she is now. At that I never should ought to of tried to kill a left-hander by hitting him in the head. Well Al they jumped all over me in the clubhouse and I had to The Library of America • Story of the Week hold myself back oErx cIe rwpto furolmd Boafs egbavll:e A s Loimtereabryo Adnyt htohloegy beating of t (The Library of America, 2002 ), pages 85 –101 . heir life. Callahan tells me I am fined $50.00 and suspended with - First published in the Saturday Evening Post (October 13, 1915 ). out no pay. I asked him What for and he says They would not be no use in telling you because you have not got no brains. I says Yes I have to got some brains and he says Yes but they is in your stumach. And then he Asaryes y Io uw irsehce wivien hg aSdto orfy soefn tth ey oWue etko eMacihlw waeueke? e and I come Sign up now at storyoftheweek.loa.org to receive our weekly alert so back at him. I says I wisyho uy wooun h’t amdis so af .single story! Ring Lardner Where Do You Get That Noise? he trade was pulled wile the Phillies was here first trip. Without T knockin’ nobody, the two fellas we give was worth about as much as a front foot on Main Street, Belgium. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

07 December 2009 CHART #1698 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Black Box Sweet Dreams I Dreamed A Dream For Your Entertainment 1 Stan Walker 21 Beyonce 1 Susan Boyle 21 Adam Lambert Last week 5 / 2 weeks SonyMusic Last week 18 / 19 weeks Platinum x1 / SonyMusic Last week 1 / 2 weeks Platinum x6 / SonyMusic Last week 8 / 2 weeks SonyMusic Whatcha Say Do You Remember? The Fame: Monster The Fall 2 Jason DeRulo 22 Jay Sean feat. Lil Jon 2 Lady Gaga 22 Norah Jones Last week 1 / 7 weeks Gold x1 / WEA/Warner Last week 23 / 2 weeks Universal Last week 3 / 51 weeks Platinum x2 / Universal Last week 18 / 3 weeks Gold x1 / BlueNote/EMI Bad Romance Uprising Harmony Jersey's Best 3 Lady Gaga 23 Muse 3 The Priests 23 Frankie Valli And The Four Seasons Last week 3 / 6 weeks Universal Last week 24 / 14 weeks WEA/Warner Last week 6 / 2 weeks SonyMusic Last week 0 / 1 weeks WEA/Warner Fireflies Live Like We're Dying This Is It Sing The Million Sellers 4 Owl City 24 Kris Allen 4 Michael Jackson 24 Foster And Allen Last week 2 / 5 weeks Gold x1 / Universal Last week 28 / 7 weeks SonyMusic Last week 2 / 6 weeks Platinum x1 / SonyMusic Last week 0 / 1 weeks BigJoke/SonyMusic Tik Tok The Fixer Holy Smoke Christmas Magic 5 Ke$ha 25 Pearl Jam 5 Gin 25 Hayley Westenra Last week 4 / 10 weeks Platinum x1 / SonyMusic Last week 25 / 15 weeks Universal Last week 4 / 7 weeks Platinum x1 / Universal Last week 22 / 3 weeks Universal Empire State Of Mind Doesn't Mean Anything The Very Best Of The E.N.D.