2018 Body & Lit Cited.Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noah Grunzweig

This Route is Prepared For: Noah Grunzweig December 13, 2013 Travel Beginning in Portland, OR www.betterworldclub.com Dear Noah Grunzweig: Here´s your CustomMaps travel packet from Better World Club. It includes specially prepared maps with narrative driving directions and a thick shaded line indicating a suggested route for your trip. Before you leave, you´ll probably want to become familiar with the packet. As you look at it, you´ll notice that some maps have only major roads and towns on the maps, to make them easy to read. In some instances, secondary highways may not appear on the map. However, the narrative directions and the shaded line will easily guide you to the road. If you desire a more detailed map, please call and we will provide you with a map of that particular area or state. As you flip through your travel packet, you´ll also see that the narrative directions provide time estimates, which you can use to figure approximate hours of drive time per day. In addition to the state maps, you´ll find we´ve also included some city maps showing more detail, to help you get your bearings. Finally, at the back end of your travel packet, you´ll find a "Places of Interest" section. Here we´ve indicated several sites for each state you´ll be driving through, just in case you´d like to stop and see something special on your way to or from your final destination. Below is your Travel Itinerary, or list of requested destinations. We trust you´ll have a safe and pleasant drive. -

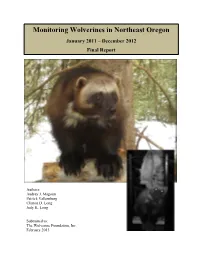

Monitoring Wolverines in Northeast Oregon

Monitoring Wolverines in Northeast Oregon January 2011 – December 2012 Final Report Authors: Audrey J. Magoun Patrick Valkenburg Clinton D. Long Judy K. Long Submitted to: The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. February 2013 Cite as: A. J. Magoun, P. Valkenburg, C. D. Long, and J. K. Long. 2013. Monitoring wolverines in northeast Oregon. January 2011 – December 2012. Final Report. The Wolverine Foundation, Inc., Kuna, Idaho. [http://wolverinefoundation.org/] Copies of this report are available from: The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. [http://wolverinefoundation.org/] Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife [http://www.dfw.state.or.us/conservationstrategy/publications.asp] Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation [http://www.owhf.org/] U. S. Forest Service [http://www.fs.usda.gov/land/wallowa-whitman/landmanagement] Major Funding and Logistical Support The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation U. S. Forest Service U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wolverine Discovery Center Norcross Wildlife Foundation Seattle Foundation Wildlife Conservation Society National Park Service 2 Special thanks to everyone who provided contributions, assistance, and observations of wolverines in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest and other areas in Oregon. We appreciate all the help and interest of the staffs of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation, U. S. Forest Service, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Wildlife Conservation Society, and the National Park Service. We also thank the following individuals for their assistance with the field work: Jim Akenson, Holly Akenson, Malin Aronsson, Norma Biggar, Ken Bronec, Steve Bronson, Roblyn Brown, Vic Coggins, Alex Coutant, Cliff Crego, Leonard Erickson, Bjorn Hansen, Mike Hansen, Hans Hayden, Tim Hiller, Janet Hohmann, Pat Matthews, David McCullough, Glenn McDonald, Jamie McFadden, Kendrick Moholt, Mark Penninger, Jens Persson, Lynne Price, Brian Ratliff, Jamie Ratliff, John Stephenson, John Wyanens, Rebecca Watters, Russ Westlake, and Jeff Yanke. -

Food Systems

Food Systems PORTLAND PLAN BACKGROUND REPORT FALL 2009 Acknowledgments Food Systems Bureau of Planning and Sustainability (BPS) PROSPERITY AND BUSINESS SUCCESS Mayor Sam Adams, Commissioner-in-charge Susan Anderson, Director SUSTAINABILITY AND THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT Joe Zehnder, Chief Planner Steve Dotterrer, Principal Planner Eric Engstrom, Principal Planner DESIGN, PLANNING AND PUBLIC SPACES Gil Kelley, Former Director, Bureau of Planning Primary Authors NEIGHBORHOODS & HOUSING Amanda Rhoads, City Planner, BPS Heidi Guenin, Community Service Aide, BPS TRANSPORTATION, TECHNOLOGY AND ACCESS Contributors Steve Cohen, Food Policy and Programs Manager, BPS EDUCATION AND SKILL DEVELOPMENT Gary Odenthal, Technical Services Manager, BPS Carmen Piekarski, GIS Analyst, BPS Portland Multnomah Food Policy Council HUMAN HEALTH, FOOD AND PUBLIC SAFETY The Food Policy Council is a citizen-based advisory council to the City of Portland and Multnomah County. The Council brings citizens QUALITY OF LIFE, CIVIC ENGAGEMENT AND EQUITY and professionals together from the region to address issues regarding food access, land use planning issues, local food purchasing ARTS, CULTURE AND INNOVATION plans and many other policy initiatives in the current regional food system. The Food Policy Council has been in conversation with BPS since 2007 regarding the Portland Plan. Two Council committees, the Land Use Committee and Food Access Committee, provided input to the development of this document in 2008, while the Urban Food Initiative/Portland Plan Committee reviewed -

John Strong Newberry, MD (1822-1892) Stuart G

John Strong Newberry, MD (1822-1892) Stuart G. Garrett, MD Bend, Oregon t the age of 33 John Strong Newberry became assistant surgeon and geologist on the 1855 War Department railroad survey. Led by Williamson and AAbbot, the mission of the expedition was to find a location for a railroad link between the San Francisco Bay area and the Columbia River, tying together the western termini of the proposed Transcontinental Railroads between the San Francisco Bay area and the Columbia River. The connec- tion was finally completed in 1927, crossing the Cascades just south of the current highway across Willamette Pass. At the time it was called Pengra Pass. As one of the first well-trained scientists to travel through much of Oregon, Newberry made many discov- eries in botany, paleontology and geology, especially in eastern Oregon. He was the first scientist to accurately interpret the drowned forests of the Columbia River as being due to landslides damming the river. (First noted by Lewis and Clark in 1807, these submerged snags are in the Columbia River between Cascade Locks and The Dalles.) Newberry was one of the first two geologists to recognize the power of water erosion in sculpting land- scapes, then known as fluvialism (O’Conner 2018). He correctly observed and interpreted glacial activity in the Cascade Mountains: “All the projecting points and ridges of the older trap rock were worn down, smoothed off, and cut by deep furrows, which now pointed northeast toward the centre of the mountain mass formed by the Three Sisters … there is little doubt that all this surface was once covered, not simply by lines of ice following the valleys, but by a continuous sheet.” He corresponded with Portrait of John Strong Newberry. -

City Club of Portland Bulletin Vol. 41, No. 19 (1960-10-7)

Portland State University PDXScholar City Club of Portland Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 10-7-1960 City Club of Portland Bulletin vol. 41, no. 19 (1960-10-7) City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.) Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub Part of the Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.), "City Club of Portland Bulletin vol. 41, no. 19 (1960-10-7)" (1960). City Club of Portland. 196. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub/196 This Bulletin is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in City Club of Portland by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. layfair Ballroom * Benson Hotel Friday... 12:10 P.M. PORTLAND, OREGON - Vol. 41, No. 1 9 - Oct. 7, 1960 (Meeting will begin promptly at 12:30. Please be seated by noon if possible.) PRINTED IN THIS ISSUE OF THE BULLETIN FOR PRESENTATION, DISCUSSION AND ACTION ON FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7,1960. REPORTS ON FINANCING IMPROVEMENTS IN HOME RULE COUNTIES (State Ballot Measure No. 11) The Committee: ROBERT BOWIN, J. R. DEVERS, WILLIAM HAMMERBECK, GEORGE A. HAY, JR., ART LIND, JOHN I. SELL, and PAUL GERHARDT, Chairman. STATE BONDS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION FACILITIES (State Ballot Measure No. 6) The Committee: NED BALL, DAN W. HOFFMAN, ROBERT KERR, CAREY MARTIN, JACK MEUSSDORFFER, DON PLYMPTON, CLARENCE RICHEN and JOHN L. -

Northwest Friend, June 1959

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church Northwest Friend (Quakers) 6-1959 Northwest Friend, June 1959 George Fox University Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_nwfriend Recommended Citation George Fox University Archives, "Northwest Friend, June 1959" (1959). Northwest Friend. 188. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_nwfriend/188 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church (Quakers) at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwest Friend by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Photo by J . Emol Swonson T H E C A L D W E L L F R I E N D S C H U R C H First used for 10th anniversary service April 26 (See story on page 12) C O M PA N Y i s C O M I N G ! Listen to Sec^ie%cttte*tde«tt'4. My mother baked a chocolate cake and as I remember, it was round, lovely and THE QUAKER HOUR very large. So large in fact, that I assumed a small piece would hardly be missed CORNER with even though company was coming for Sunday dinner the next day. So when I took the MILO C. ROSS slice late Saturday evening after the cake was put away in the cupboard, my con science was hardly stirred. But it was next noon when company came. And my Oregon: entire little anatomy was shaken soundly when the cake was fetched into use before KWJJ, Portland, 1:00p.m. -

Monitoring Wolverines in Northeast Oregon

Monitoring Wolverines in Northeast Oregon January 2011 – December 2012 Final Report Authors: Audrey J. Magoun Patrick Valkenburg Clinton D. Long Judy K. Long Submitted to: The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. February 2013 Cite as: A. J. Magoun, P. Valkenburg, C. D. Long, and J. K. Long. 2013. Monitoring wolverines in northeast Oregon. January 2011 – December 2012. Final Report. The Wolverine Foundation, Inc., Kuna, Idaho. [http://wolverinefoundation.org/] Copies of this report are available from: The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. [http://wolverinefoundation.org/] Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife [http://www.dfw.state.or.us/conservationstrategy/publications.asp] Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation [http://www.owhf.org/] U. S. Forest Service [http://www.fs.usda.gov/land/wallowa-whitman/landmanagement] Major Funding and Logistical Support The Wolverine Foundation, Inc. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation U. S. Forest Service U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wolverine Discovery Center Norcross Wildlife Foundation Seattle Foundation Wildlife Conservation Society National Park Service 2 Special thanks to everyone who provided contributions, assistance, and observations of wolverines in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest and other areas in Oregon. We appreciate all the help and interest of the staffs of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation, U. S. Forest Service, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Wildlife Conservation Society, and the National Park Service. We also thank the following individuals for their assistance with the field work: Jim Akenson, Holly Akenson, Malin Aronsson, Norma Biggar, Ken Bronec, Steve Bronson, Roblyn Brown, Vic Coggins, Alex Coutant, Cliff Crego, Leonard Erickson, Bjorn Hansen, Mike Hansen, Hans Hayden, Tim Hiller, Janet Hohmann, Pat Matthews, David McCullough, Glenn McDonald, Jamie McFadden, Kendrick Moholt, Mark Penninger, Jens Persson, Lynne Price, Brian Ratliff, Jamie Ratliff, John Stephenson, John Wyanens, Rebecca Watters, Russ Westlake, and Jeff Yanke. -

The Oregon State Emergency Alert System Plan

THE OREGON STATE EMERGENCY ALERT SYSTEM PLAN VERSION 14 February 22, 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Intent and Purpose oF this Plan 2. The National, State, and Local EAS Participation and Priorities 3. State/Local EAS Participation 4. EAS Priorities 5. The Oregon State Emergency Communications Committee (THE SECC.) 6. EAS Designations. 7. Delivery Plan / Monitoring Assignments 8. Local Plans 9. Origins oF EAS InFormation. A. National-Level System B. State Level System. C. Weather Emergencies. D. Local Emergencies. 10. The EAS Message. 11. Testing A. Required Weekly Test (RWT) B. Required Monthly Test (RMT) 12. Guidance For Originators oF EAS Alerts 13. CertiFication 2 LIST OF TABS Tab 1 Membership List oF the SECC. Tab 2 List oF the operational areas and the Local Chair Persons Tab 3 SpeciFic InFormation oF the National, Statewide and Local Alerting System Plans. 1. The Presidents message. A county by county list of message distribution. 2. Statewide messages using the legacy EAS system, using the SAME protocol 3. SpeciFic inFormation using the common alerting protocol For all messages 4. Statewide messages using the common alerting protocol 5. Local messages using the legacy EAS system using the SAME protocol 6. Local messages using the common alerting protocol 7. Local emergencies generated through the statewide system Tab 4 SpeciFic inFormation oF the use oF NOAA weather Radio For Weather Emergencies. Tab 5 Outlines oF Local Plans. A list oF each operational area’s chairperson, originators, state primary stations, local primary stations, and weather radio stations Tab 6 The Common Alerting Protocol 1. Description oF the Common Alerting Protocol 2. -

Check out Our Footage from Our Idaho / Oregon Trip! Salinas - Partly Cloudy to Sunny for the Upcoming Week with Highs in the 60S & 70S and Lows in the 50S

Check out our footage from our Idaho / Oregon Trip! Salinas - Partly cloudy to sunny for the upcoming week with highs in the 60s & 70s and lows in the 50s. Oxnard - Sunny for the upcoming week with highs in the 70s and lows in the 50s. Mexico (Culiacan)- Partly cloudy with thunderstorms for the next seven days; highs in the 90s and lows in the 60s. Florida, Southern– Thunderstorms are back for the next week with highs around 90 and lows in the 70s. Idaho - Partly cloudy to sunny next week with a chance of rain and snow! Highs around 50 and lows in the high 20s. Winter is coming! The National Diesel Average has been recorded at $3.313 up $0.041 a Jalapenos gal from last week and up $0.511 gal from last year. NPC continues to Citrus monitor and track diesel fuel averages by state as well as reported truckload freight rates on a weekly basis. Transportation continues to Green Onions work through its most significant structural changes in years in re- Cilantro gards to new laws and regulations stressing available truck volume Green Cabbage and controlling drivers. There is a pretty consistent slight shortage across the rest of the country. www.nproduce.com (800) 213-6699 October 7, 2018 | Page 1 MARKET OUTLOOK Apples QUALITY SUPPLY Washington is down on volumes with Reds, Golds and Fujis and considerably down on Galas (15% down) and an amazing 30% down on gr smiths. Volume will be confirmed as the State continue to harvest in the Month of October. -

Referendum on Uniform Standard Time Providing Uniform Standard Time in Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar City Club of Portland Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 9-15-1950 Referendum on Uniform Standard Time providing Uniform Standard Time in Oregon City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.) Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub Part of the Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.), "Referendum on Uniform Standard Time providing Uniform Standard Time in Oregon" (1950). City Club of Portland. 141. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub/141 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in City Club of Portland by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. PORTLAND CITY CLUB BULLETIN 61 Report On REFERENDUM ON UNIFORM STANDARD TIME PROVIDING UNIFORM STANDARD TIME IN OREGON Purpose: To establish uniform standard time in Oregon; authorizes governor to vary such standard Oregon time by not more than one hour, upon making a formal finding of fact that the economy and general welfare of this state are at material disadvantage by lack of uniformity between standard Oregon time with the time in general use in states bordering on Oregon. Such fact to appear by a proclamation and published throughout the state, showing necessity for varying the uniform standard time to eliminate such condition. Thereafter standard Oregon time shall be and exist as stated in such proclamation. 310 Yes 311 No To the Board of Governors The City Club of Portland: In its investigation your committee decided it was both unnecessary and unwise to take a position for or against daylight saving time. -

Biological Soil Crust Survey, Rome Cliff Areas

Biological Soil Crust Survey - Rome Cliffs Area, T31S, R41E, Sec. 32, Malheur County, Oregon Original prepared for the Bureau of Land Management Oregon State Office January 28, 2010 (Revisions, additions – September 1, 2016) Ann DeBolt 2032 South Crystal Way Boise, ID 83706 [email protected] Abstract During a 2009 biological soil crust survey of the Rome Cliffs area in southeast Oregon, forty-six species of lichens, bryophytes, and cyanobacteria taxa were identified. Of the 46 taxa, there were 38 lichens (36 on soil, 1 on wood, 1 on pebbles), 6 bryophytes (mosses/liverworts; soil), and 2 cyanobacteria (soil). The lichen Placidium acarosporoides is reported as new for Oregon. Heteroplacidium congestum, Lecidea laboriosa, and Acarospora obpallens, each collected during this Rome Cliffs survey, have been reported one other time from Oregon, all from Deschutes County, and all by different collectors over a period of 40+ years. Soil types and vegetation differed considerably among the four study plots, as reflected by the biological soil crusts, with up to eleven taxa unique to one of the plots. Overall biological soil crust diversity ranged from 14 to 26 species per 1 acre plot. This survey exemplifies the diversity and richness found within this micro-flora, and illustrates just how poorly known it is. Introduction The Rome Cliffs Area and associated zeolite deposits are located in the vicinity of Rome, Oregon, approximately 130 km southwest of the town of Vale. Neogene and Quaternary volcanic and sedimentary rocks are the primary outcroppings in this area (Sheppard 1987). The zeolites and associated minerals occur in a sequence of alluvial and lacustrine volcaniclastic rocks known informally as the Rome beds (Sheppard 1987). -

Check out Our Footage from Our Idaho / Oregon Trip! Salinas - Sunny for the Upcoming Week with Highs in the Low 70S and Lows in the 50S

Check out our footage from our Idaho / Oregon Trip! Salinas - Sunny for the upcoming week with highs in the low 70s and lows in the 50s. Oxnard - Sunny for the upcoming week with highs in the 70s and lows in the 60s and high 50s. Mexico (Culiacan)- Sunny for the upcoming week with highs in the 90s and lows in the high 60s. Florida, Southern– Scattered thunderstorms with highs in the 80s and lows in the 70s. Idaho - Sunny for the upcoming week with highs in the 60s and high 50s and lows in the 30s. The National Diesel Average has been recorded at $3.385 up $0.072 a Jalapenos gal from last week and up $0.511 gal from last year. NPC continues to Citrus monitor and track diesel fuel averages by state as well as reported truckload freight rates on a weekly basis. Transportation continues to Green Onions work through its most significant structural changes in years in re- Cilantro gards to new laws and regulations stressing available truck volume Green Cabbage and controlling drivers. Truck availability is adequate nationally. Green Beans www.nproduce.com (800) 213-6699 October 12, 2018 | Page 1 MARKET OUTLOOK Apples QUALITY SUPPLY Washington is down on volumes with Reds, Golds and Fujis and considerably down on Galas (15% down) and an amazing 30% down on gr smiths. Volume will be confirmed as the State continue to harvest in the Month of October. Reds and Golds are down significant due to growers cutting their orchards down to replant Hon- eys, Pinks, Organics, Jazz, Lady Alice, etc.