What You Need to Know About Wolf-Dog Hybrids-04-2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

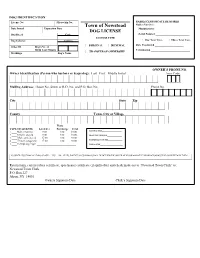

Dog License Application

DOG IDENTIFICATION License No. Microchip No. RABIES CERTIFICATE REQUIRED Rabies Vaccine: Town of Newstead Date Issued Expiration Date Manufacturer __________________________ DOG LICENSE Serial Number __________________________ Dog Breed Code LICENSE TYPE Dog Color(s) Code(s) One Year Vacc. Three Year Vacc. ORIGINAL RENEWAL Date Vaccinated ______________________ Other ID Dog’s Yr. of Birth Last 2 Digits Veterinarian ______________________________ TRANSFER OF OWNERSHIP Markings Dog’s Name OWNER’S PHONE NO. Owner Identification (Person who harbors or keeps dog): Last First Middle Initial Area Code Mailing Address: House No. Street or R.D. No. and P.O. Box No. Phone No. City State Zip County Town, City or Village State TYPE OF LICENSE Local Fee Surcharge Total 1.____Male, neutered 9.00 1.00= 10.00 LICENSE FEE____________________ 2.____Female, spayed 9.00 1.00= 10.00 SPAY/NEUTER FEE_______________ 3.____ Male, unneutered 17.00 3.00= 20.00 4.____ Female, unspayed 17.00 3.00= 20.00 ENUMERATION FEE______________ 5.____Exempt dog Type: ______________________________ TOTAL FEE______________________ _ ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ IS OWNER LESS THAN 18 YEARS OF AGE? YES NO IF YES, PARENT Owner’s OR GUARDIANSignature SHALL BE DEEMED THE OWNERDate OF RECORD AND THEClerk’s INFORMATION Signature MUST BE COMPLETEDDate BY THEM. Return form, current rabies certificate, spay/neuter certificate (if applicable) and check made out to “Newstead Town Clerk” to: Newstead Town Clerk P.O. Box 227 Akron, NY 14001 _____________________________________ ___________________________________________ Owners Signature/Date Clerk’s Signature/Date OWNER’S INSTRUCTIONS 1. All dogs 4 months of age or older are to be licensed. In addition, any dog under 4 months of age, if running at large must be licensed. -

Aggression in Dogs an Overview

Behavior & Training 415.506.6280 Available B&T Services Aggression in Dogs: An Overview What is the behavior? Aggression is a natural behavior, not an aberration. Most aggression is defensive in nature – that is, the dog is reacting to what he perceives as a threat. Behavior is always in flux, and can get worse before it gets better. If your dog is aggressive, you must decide: Whether your dog is too dangerous to work with. Whether the behavior can be kept under control by managing the environment. Whether you have the ability to modify the behavior. Whether you have the time and commitment to do so. Know your dog and his body language - from behind your dog as well as beside or in front. Dogs, after all, often walk ahead of their owner. (Please review our Body Language: Speaking “Dog” handout.) Observe your dog's body language when relaxed. Observe your dog's body language when tense. Observe the DISTANCE between your dog and the object of interest. Observe your dog's body language when he is about to attack. Observe EXACTLY what sets off your dog: children/other dogs/other male or female dogs/men with beards/people in uniform. Know your own response to stress. Note what you or your family members do when your dog looks like he might aggress or when you are worried while with your dog. How do you modify the behavior? This handout will discuss some of the reasons a dog may behave aggressively and is only an overview of aggressive displays. To build an individualized behavior modification program for your dog’s needs, please contact Behavior & Training to schedule a consultation. -

Comparative Study of Free-Roaming Domestic Dog Management and Roaming Behavior Across Four Countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 Comparative study of free-roaming domestic dog management and roaming behavior across four countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda Warembourg, Charlotte ; Wera, Ewaldus ; Odoch, Terence ; Bulu, Petrus Malo ; Berger-González, Monica ; Alvarez, Danilo ; Abakar, Mahamat Fayiz ; Maximiano Sousa, Filipe ; Cunha Silva, Laura ; Alobo, Grace ; Bal, Valentin Dingamnayal ; López Hernandez, Alexis Leonel ; Madaye, Enos ; Meo, Maria Satri ; Naminou, Abakar ; Roquel, Pablo ; Hartnack, Sonja ; Dürr, Salome Abstract: Dogs play a major role in public health because of potential transmission of zoonotic diseases, such as rabies. Dog roaming behavior has been studied worldwide, including countries in Asia, Latin America, and Oceania, while studies on dog roaming behavior are lacking in Africa. Many of those studies investigated potential drivers for roaming, which could be used to refine disease control measures. However, it appears that results are often contradictory between countries, which could be caused by differences in study design or the influence of context-specific factors. Comparative studiesondog roaming behavior are needed to better understand domestic dog roaming behavior and address these discrepancies. The aim of this study was to investigate dog demography, management, and roaming behavior across four countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda. We equipped 773 dogs with georeferenced contact sensors (106 in Chad, 303 in Guatemala, 217 in Indonesia, and 149 in Uganda) and interviewed the owners to collect information about the dog [e.g., sex, age, body condition score (BCS)] and its management (e.g., role of the dog, origin of the dog, owner-mediated transportation, confinement, vaccination, and feeding practices). -

Dog” Looks Back at “God”: Unfixing Canis Familiaris in Kornél Mundruczó’S † Film Fehér Isten/White God (2014)

humanities Article Seeing Beings: “Dog” Looks Back at “God”: Unfixing Canis familiaris in Kornél Mundruczó’s † Film Fehér isten/White God (2014) Lesley C. Pleasant Department of Foreign Languages and Cultures, University of Evansville, Evansville, IN 47714, USA; [email protected] † I have had to rely on the English subtitles of this film, since I do not speak Hungarian. I quote from the film in English, since the version to which I have had access does not give the option of Hungarian subtitles. Received: 6 July 2017; Accepted: 13 October 2017; Published: 1 November 2017 Abstract: Kornél Mundruczó’s film Fehér isten/White God (2014) portrays the human decreed options of mixed breed, abandoned dogs in the streets of Budapest in order to encourage its viewers to rethink their relationship with dogs particularly and animals in general in their own lives. By defamiliarizing the familiar ways humans gaze at dogs, White God models the empathetic gaze between species as a potential way out of the dead end of indifference and the impasse of anthropocentric sympathy toward less hierarchical, co-created urban animal publics. Keywords: animality; dogs; film; White God; empathy 1. Introduction Fehér isten/White God (2014) is not the first film use mixed breed canine actors who were saved from shelters1. The Benji films starred mixed breed rescued shelter dogs (McLean 2014, p. 7). Nor is it unique in using 250 real screen dogs instead of computer generated canines. Disney’s 1996 101 Dalmations starred around 230 Dalmation puppies and 20 adult Dalmations (McLean 2014, p. 20). It is also certainly not the only film with animal protagonists to highlight Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody # 2 in its soundtrack. -

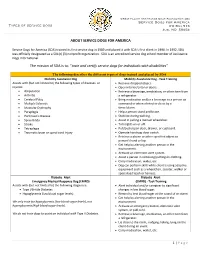

Train and Certify Service Dogs for Individuals with Disabilities”

Great Plains Assistance Dogs Foundation dba Service Dogs for America Types of service dogs PO Box 513 Jud, ND 58454 ABOUT SERVICE DOGS FOR AMERICA Service Dogs for America (SDA) trained its first service dog in 1989 and placed it with SDA’s first client in 1990. In 1992, SDA was officially designated as a 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization. SDA is an accredited service dog school member of Assistance Dogs International. The mission of SDA is to: “train and certify service dogs for individuals with disabilities” The following describes the different types of dogs trained and placed by SDA Mobility Assistance Dog Mobility Assistance Dog ‐ Task Training Assists with (but not limited to) the following types of diseases or Retrieve dropped object. injuries: Open interior/exterior doors. Amputation Retrieve a beverage, medication, or other item from Arthritis a refrigerator. Cerebral Palsy Bring medication and/or a beverage to a person on Multiple Sclerosis command or when alerted to do so by a Muscular Dystrophy timer/alarm. Paraplegia Help a person stand and brace. Parkinson’s Disease Stabilize during walking. Spina Bifida Assist in pulling a manual wheelchair. Stroke Turn lights on or off. Tetraplegia Pull/push/open door, drawer, or cupboard. Traumatic brain or spinal cord injury Operate handicap door switch. Retrieve a phone or other specified object to person’s hand or lap. Get help by alerting another person in the environment. Activate an electronic alert system. Assist a person in removing/putting on clothing. Carry medication, wallet, etc. Dog can perform skills while client is using adaptive equipment such as a wheelchair, scooter, walker or specialized leash or harness. -

Understanding Dog Behavior & How the Handler Can Influence It For

Understanding Dog Behavior & How the Handler can Influence it for Better or Worse Sara Heesacker RMC NAHVDA Director of Training A LOOK ON THE INSIDE Frontal Lobe- Involved in intellectual function, multitasking, strategic planning Olfactory bulb - Only sense that goes directly to area in brain Hippocampus - Responsible for value system in dog’s mind THE SENSES TELL THE STORY Taste - Humans 9000 taste buds Dogs 1706 taste buds Hearing -Dogs hear 4 times the distance of humans Sight- Diurnal 6 times weaker eyesight NO PROBLEM FINDING SCENT… It’s about sorting out the multitude of scents that are there already Most critical sense but most difficult for humans to comprehend HORMONES BEHIND LEARNING Dopamine- related to reward and movement Have to search it out and problem solve Endorphins – “runners high” Designed to make you continue to fight Serotonin- linked to emotional balance lick and chew/ replay Cortisol – “stress hormone” Shrinks brain network DOG TOO STRESSED TO EAT TOO STRESSED TO LEARN HOW IT ALL WORKS Cognition requires use of • Mind • Intelligence • Learned behavior How does Obedience PERCEPTION NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION Small movements make a big change in dog’s behavior • Unconscious of hands • How we tilt a head • We radiate random signals Dogs watch our eyes • communicate authority READING DOGS DEVELOPING YOUR EYE • Leaning toward me, away from me, standing square over all four paws • Frozen still, breathing normally, breathing too fast with shallow breaths • Corners of mouth (commissure) go forward or backwards • Eyes soft -

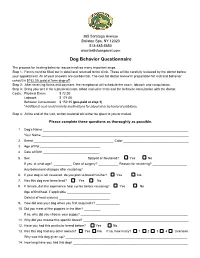

Dog Behavior Questionnaire

365 Saratoga Avenue Ballston Spa, NY 12020 518-885-5650 www.ballstonspavet.com Dog Behavior Questionnaire The process for treating behavior issues involves many important steps. Step 1: Forms must be filled out in detail and returned to the clinic. These will be carefully reviewed by the doctor before your appointment. All of your answers are confidential. The cost for doctor review in preparation for visit and behavior consult is $152.25, paid at form drop-off. Step 2: After receiving forms and payment, the receptionist will schedule the exam, labwork and consultation. Step 3: Bring your pet in for a physical exam, blood and urine tests and the behavior consultation with the doctor. Costs: Physical Exam $ 72.00 Labwork $ 171.00 Behavior Consultation $ 152.25 (pre-paid at step 1) *Additional cost could include medications for physical or behavioral problems. Step 4: At the end of the visit, written material will either be given to you or mailed. Please complete these questions as thoroughly as possible. 1. Dog’s Name ________________________________________________________________________________ Your Name _________________________________________________________________________________ 2. Breed ____________________________________________ Color ____________________________________ 3. Age of Pet _________________________________ 4. Date of Birth _______________________________ 5. Sex _______________________________ Spayed or Neutered? Yes No If yes, at what age? __________ Date of surgery? ___________ Reason for neutering? ___________________ Any behavioral changes after neutering? _________________________________________________________ 6. If your dog is not neutered, do you plan to breed him/her? Yes No 7. Has this dog ever been bred? Yes No 8. If female, did she experience heat cycles before neutering? Yes No Age of first heat, if applicable ________________________ Date(s) of heat cycle(s) ____________________________ 9. -

Less Than Exciting Behaviors Associated with Unneutered

1 c Less Than Exciting ASPCA Behaviors Associated With Unneutered Male Dogs! Periodic binges of household destruction, digging and scratching. Indoor restlessness/irritability. N ATIONAL Pacing, whining, unable to settle down or focus. Door dashing, fence jumping and assorted escape behaviors; wandering/roaming. Baying, howling, overbarking. Barking/lunging at passersby, fence fighting. Lunging/barking at and fighting with other male dogs. S HELTER Noncompliant, pushy and bossy attitude towards caretakers and strangers. Lack of cooperation. Resistant; an unwillingness to obey commands; refusal to come when called. Pulling/dragging of handler outdoors; excessive sniffing; licking female urine. O UTREACH Sexual frustration; excessive grooming of genital area. Sexual excitement when petted. Offensive growling, snapping, biting, mounting people and objects. Masturbation. A heightened sense of territoriality, marking with urine indoors. Excessive marking on outdoor scent posts. The behaviors described above can be attributed to unneutered male sexuality. The male horomone D testosterone acts as an accelerant making the dog more reactive. As a male puppy matures and enters o adolescence his primary social focus shifts from people to dogs; the human/canine bond becomes g secondary. The limited attention span will make any type of training difficult at best. C a If you are thinking about breeding your dog so he can experience sexual fulfillment ... don’t do it! This r will only let the dog ‘know what he’s missing’ and will elevate his level of frustration. If you have any of e the problems listed above, they will probably get worse; if you do not, their onset may be just around the corner. -

Behavioural Risks in Male Dogs with Minimal Lifetime Exposure to Gonadal Hormones May Complicate Population-Control Benefits of Desexing

RESEARCH ARTICLE Behavioural risks in male dogs with minimal lifetime exposure to gonadal hormones may complicate population-control benefits of desexing Paul D. McGreevy1*, Bethany Wilson1, Melissa J. Starling1, James A. Serpell2 1 Sydney School of Veterinary Science, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 2 School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 Castration of dogs is a widespread practise with clear justification in population control and knock-on benefits for animal welfare. Deleterious behavioural consequences of castration are believed to be negligible. Gonadectomy is widely recommended as part of a multi-facto- OPEN ACCESS rial approach to prevent problems including aggression in dogs. However, the conse- quences of early castration on health are still being debated. The current study focused on Citation: McGreevy PD, Wilson B, Starling MJ, Serpell JA (2018) Behavioural risks in male dogs the reported behaviour of 6,235 male dogs castrated before 520 weeks of life for reasons with minimal lifetime exposure to gonadal other than behavioural management, and calculated their percentage lifetime exposure to hormones may complicate population-control gonadal hormones (PLGH) as a proportion of their age at the time of being reported to the benefits of desexing. PLoS ONE 13(5): e0196284. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196284 online Canine Behavioral Assessment and Research Questionnaire (C-BARQ). Forty behaviors differed between entire and castrated dogs, of which 25 were associated with Editor: Arda Yildirim, Gaziosmanpasa University, TURKEY PLGH and 14 with age-at-castration (AAC). -

Canine-Centered Interface Design: Supporting the Work of Diabetes Alert Dogs Charlotte Robinson1, Clara Mancini1, Janet Van Der Linden1, Claire Guest2, Rob Harris2

Session: Participatory Design CHI 2014, One of a CHInd, Toronto, ON, Canada Canine-Centered Interface Design: Supporting the Work of Diabetes Alert Dogs Charlotte Robinson1, Clara Mancini1, Janet van der Linden1, Claire Guest2, Rob Harris2 1Open University 2Medical Detection Dogs Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK Great Horwood MK17 0NP, UK {charlotte.robinson, clara.mancini, {claire.guest, rob.harris} janet.vanderlinden} @open.ac.uk @medicaldetectiondogs.org.uk ABSTRACT have been researched and developed which use skin Many people with Diabetes live with the continuous threat conductance or glucose sensors [2, 6]. However, these of hypoglycemic attacks and the danger of going into coma. machines have a certain margin of error and are often not a Diabetes Alert Dogs are trained to detect the onset of an practical stand-alone solution to manage day to day attack before the condition of the human handler they are hypoglycaemic attacks [10]. paired with deteriorates, giving them time to take action. We investigated requirements for designing an alarm As a result, Diabetes Alert Dogs (DAD) have increased in system allowing dogs to remotely call for help when their popularity over the last two decades. DADs are paired with human falls unconscious before being able to react to an human diabetes patients and are trained to warn their alert. Through a multispecies ethnographic approach we owners of oncoming hypoglycaemic attacks, giving them focus on the requirements for a physical canine user time to call for help or take steps to prevent the attack [23]. interface, involving dogs, their handlers and specialist dog Diabetic alert dogs use their olfactory capabilities to detect trainers in the design process. -

Aggression Types Performed by Dogs Registered in an Italian Sanitary District: Preliminary Results

Aggression types performed by dogs registered in an Italian sanitary district: preliminary results Erika Zannardiab*, Piero Gellib, Roberto Mattellinib a Veterinary behaviorist, b Struttura complessa Sanita Animale Asl 5 La Spezia-Italy Abstract: Aim of this research was to classify the distinct types of canine aggression registered by the public vet- erinary service in a sanitary district of Liguria, Italy (ASL 5 Spezzino, La Spezia - Italy). The data sheets of biter dogs, recorded in the registers of ASL 5, also containing a space to report the accurate description of the aggression that permitted its classification by a veterinary behaviorist were used. The information was obtained examining 1,389 records, referring to the period from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2016. The aggressive episodes coded were: irrita- tion (n=137), redirect (n=107), territorial (n=81), protective (n=76), play (n=64), fear (n=48), predatory (n=35), food (n=26), possessive (n=18) and maternal (n=1). Canine aggression is one of the most felt problems by the public opinion and it can constitute a serious danger to the safety of people. In the past, attention was paid to the analysis of the dog bites from different points of view, try- ing to correlate them to the period, the breed and sex of the animal, but little attention was paid to the identification of the type of aggression. In conclusions these first data, although preliminary, could be useful to better prevent the most frequent forms of aggression among those reported to the health authority. Key Words: dog, aggression. * Corresponding Author: [email protected] Introduction Canine aggression is a very relevant event because, if directed towards people, it constitutes a public health problem. -

CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation Acknowledgements with Grateful Thanks To: the Kennel Club, Battersea (Dogs & Cats Home) & Prof

CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation Acknowledgements With grateful thanks to: The Kennel Club, Battersea (Dogs & Cats Home) & Prof. Sheila Crispin MA BScPhD VetMB MRCVS for providing diagrams and images Google, for any images made available through their re-use policy Please note that images throughout the Guidance are subject to copyright and permissions must be obtained for further use. Index 1. Introduction 5 2. Conformation 5 3. Legislation 5 4. Impact of poor conformation 6 5. Conformation & physical appearance 6 Eyes, eyelids & area surrounding the eye 7 Face shape – flat-faced (brachycephalic) dog types 9 Mouth, dentition & jaw 11 Ears 12 Skin & coat 13 Back, legs & locomotion 14 Tail 16 6. Summary of Key Points 17 7. Resources for specific audiences & actions they can take to support good dog conformation 18 Annex 1: Legislation, Guidance & Codes of Practice 20 1. Legislation in England 20 Regulations & Guidance Key sections of Regulations & Guidance relevant to CFSG sub-group on dog conformation Overview of the conditions and explanatory guidance of the Regulations 2. How Welfare Codes of Practice & Guidance support Animal Welfare legislation 24 Defra’s Code of Practice for the Welfare of Dogs Animal Welfare Act 2006 Application of Defra Code of Practice for the Welfare of Dogs in supporting dog welfare 3. The role of the CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation in supporting dog welfare 25 CFSG Guidance on Dog Conformation 3 Annex 2: Key points to consider if intending to breed from or acquire either an adult dog or a puppy 26 Points