Implications of Weaning Age for Dog Welfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aggression in Dogs an Overview

Behavior & Training 415.506.6280 Available B&T Services Aggression in Dogs: An Overview What is the behavior? Aggression is a natural behavior, not an aberration. Most aggression is defensive in nature – that is, the dog is reacting to what he perceives as a threat. Behavior is always in flux, and can get worse before it gets better. If your dog is aggressive, you must decide: Whether your dog is too dangerous to work with. Whether the behavior can be kept under control by managing the environment. Whether you have the ability to modify the behavior. Whether you have the time and commitment to do so. Know your dog and his body language - from behind your dog as well as beside or in front. Dogs, after all, often walk ahead of their owner. (Please review our Body Language: Speaking “Dog” handout.) Observe your dog's body language when relaxed. Observe your dog's body language when tense. Observe the DISTANCE between your dog and the object of interest. Observe your dog's body language when he is about to attack. Observe EXACTLY what sets off your dog: children/other dogs/other male or female dogs/men with beards/people in uniform. Know your own response to stress. Note what you or your family members do when your dog looks like he might aggress or when you are worried while with your dog. How do you modify the behavior? This handout will discuss some of the reasons a dog may behave aggressively and is only an overview of aggressive displays. To build an individualized behavior modification program for your dog’s needs, please contact Behavior & Training to schedule a consultation. -

Comparative Study of Free-Roaming Domestic Dog Management and Roaming Behavior Across Four Countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 Comparative study of free-roaming domestic dog management and roaming behavior across four countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda Warembourg, Charlotte ; Wera, Ewaldus ; Odoch, Terence ; Bulu, Petrus Malo ; Berger-González, Monica ; Alvarez, Danilo ; Abakar, Mahamat Fayiz ; Maximiano Sousa, Filipe ; Cunha Silva, Laura ; Alobo, Grace ; Bal, Valentin Dingamnayal ; López Hernandez, Alexis Leonel ; Madaye, Enos ; Meo, Maria Satri ; Naminou, Abakar ; Roquel, Pablo ; Hartnack, Sonja ; Dürr, Salome Abstract: Dogs play a major role in public health because of potential transmission of zoonotic diseases, such as rabies. Dog roaming behavior has been studied worldwide, including countries in Asia, Latin America, and Oceania, while studies on dog roaming behavior are lacking in Africa. Many of those studies investigated potential drivers for roaming, which could be used to refine disease control measures. However, it appears that results are often contradictory between countries, which could be caused by differences in study design or the influence of context-specific factors. Comparative studiesondog roaming behavior are needed to better understand domestic dog roaming behavior and address these discrepancies. The aim of this study was to investigate dog demography, management, and roaming behavior across four countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda. We equipped 773 dogs with georeferenced contact sensors (106 in Chad, 303 in Guatemala, 217 in Indonesia, and 149 in Uganda) and interviewed the owners to collect information about the dog [e.g., sex, age, body condition score (BCS)] and its management (e.g., role of the dog, origin of the dog, owner-mediated transportation, confinement, vaccination, and feeding practices). -

Train and Certify Service Dogs for Individuals with Disabilities”

Great Plains Assistance Dogs Foundation dba Service Dogs for America Types of service dogs PO Box 513 Jud, ND 58454 ABOUT SERVICE DOGS FOR AMERICA Service Dogs for America (SDA) trained its first service dog in 1989 and placed it with SDA’s first client in 1990. In 1992, SDA was officially designated as a 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization. SDA is an accredited service dog school member of Assistance Dogs International. The mission of SDA is to: “train and certify service dogs for individuals with disabilities” The following describes the different types of dogs trained and placed by SDA Mobility Assistance Dog Mobility Assistance Dog ‐ Task Training Assists with (but not limited to) the following types of diseases or Retrieve dropped object. injuries: Open interior/exterior doors. Amputation Retrieve a beverage, medication, or other item from Arthritis a refrigerator. Cerebral Palsy Bring medication and/or a beverage to a person on Multiple Sclerosis command or when alerted to do so by a Muscular Dystrophy timer/alarm. Paraplegia Help a person stand and brace. Parkinson’s Disease Stabilize during walking. Spina Bifida Assist in pulling a manual wheelchair. Stroke Turn lights on or off. Tetraplegia Pull/push/open door, drawer, or cupboard. Traumatic brain or spinal cord injury Operate handicap door switch. Retrieve a phone or other specified object to person’s hand or lap. Get help by alerting another person in the environment. Activate an electronic alert system. Assist a person in removing/putting on clothing. Carry medication, wallet, etc. Dog can perform skills while client is using adaptive equipment such as a wheelchair, scooter, walker or specialized leash or harness. -

Understanding Dog Behavior & How the Handler Can Influence It For

Understanding Dog Behavior & How the Handler can Influence it for Better or Worse Sara Heesacker RMC NAHVDA Director of Training A LOOK ON THE INSIDE Frontal Lobe- Involved in intellectual function, multitasking, strategic planning Olfactory bulb - Only sense that goes directly to area in brain Hippocampus - Responsible for value system in dog’s mind THE SENSES TELL THE STORY Taste - Humans 9000 taste buds Dogs 1706 taste buds Hearing -Dogs hear 4 times the distance of humans Sight- Diurnal 6 times weaker eyesight NO PROBLEM FINDING SCENT… It’s about sorting out the multitude of scents that are there already Most critical sense but most difficult for humans to comprehend HORMONES BEHIND LEARNING Dopamine- related to reward and movement Have to search it out and problem solve Endorphins – “runners high” Designed to make you continue to fight Serotonin- linked to emotional balance lick and chew/ replay Cortisol – “stress hormone” Shrinks brain network DOG TOO STRESSED TO EAT TOO STRESSED TO LEARN HOW IT ALL WORKS Cognition requires use of • Mind • Intelligence • Learned behavior How does Obedience PERCEPTION NON-VERBAL COMMUNICATION Small movements make a big change in dog’s behavior • Unconscious of hands • How we tilt a head • We radiate random signals Dogs watch our eyes • communicate authority READING DOGS DEVELOPING YOUR EYE • Leaning toward me, away from me, standing square over all four paws • Frozen still, breathing normally, breathing too fast with shallow breaths • Corners of mouth (commissure) go forward or backwards • Eyes soft -

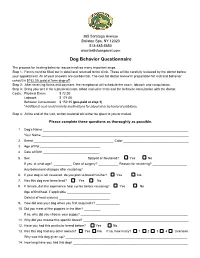

Dog Behavior Questionnaire

365 Saratoga Avenue Ballston Spa, NY 12020 518-885-5650 www.ballstonspavet.com Dog Behavior Questionnaire The process for treating behavior issues involves many important steps. Step 1: Forms must be filled out in detail and returned to the clinic. These will be carefully reviewed by the doctor before your appointment. All of your answers are confidential. The cost for doctor review in preparation for visit and behavior consult is $152.25, paid at form drop-off. Step 2: After receiving forms and payment, the receptionist will schedule the exam, labwork and consultation. Step 3: Bring your pet in for a physical exam, blood and urine tests and the behavior consultation with the doctor. Costs: Physical Exam $ 72.00 Labwork $ 171.00 Behavior Consultation $ 152.25 (pre-paid at step 1) *Additional cost could include medications for physical or behavioral problems. Step 4: At the end of the visit, written material will either be given to you or mailed. Please complete these questions as thoroughly as possible. 1. Dog’s Name ________________________________________________________________________________ Your Name _________________________________________________________________________________ 2. Breed ____________________________________________ Color ____________________________________ 3. Age of Pet _________________________________ 4. Date of Birth _______________________________ 5. Sex _______________________________ Spayed or Neutered? Yes No If yes, at what age? __________ Date of surgery? ___________ Reason for neutering? ___________________ Any behavioral changes after neutering? _________________________________________________________ 6. If your dog is not neutered, do you plan to breed him/her? Yes No 7. Has this dog ever been bred? Yes No 8. If female, did she experience heat cycles before neutering? Yes No Age of first heat, if applicable ________________________ Date(s) of heat cycle(s) ____________________________ 9. -

Less Than Exciting Behaviors Associated with Unneutered

1 c Less Than Exciting ASPCA Behaviors Associated With Unneutered Male Dogs! Periodic binges of household destruction, digging and scratching. Indoor restlessness/irritability. N ATIONAL Pacing, whining, unable to settle down or focus. Door dashing, fence jumping and assorted escape behaviors; wandering/roaming. Baying, howling, overbarking. Barking/lunging at passersby, fence fighting. Lunging/barking at and fighting with other male dogs. S HELTER Noncompliant, pushy and bossy attitude towards caretakers and strangers. Lack of cooperation. Resistant; an unwillingness to obey commands; refusal to come when called. Pulling/dragging of handler outdoors; excessive sniffing; licking female urine. O UTREACH Sexual frustration; excessive grooming of genital area. Sexual excitement when petted. Offensive growling, snapping, biting, mounting people and objects. Masturbation. A heightened sense of territoriality, marking with urine indoors. Excessive marking on outdoor scent posts. The behaviors described above can be attributed to unneutered male sexuality. The male horomone D testosterone acts as an accelerant making the dog more reactive. As a male puppy matures and enters o adolescence his primary social focus shifts from people to dogs; the human/canine bond becomes g secondary. The limited attention span will make any type of training difficult at best. C a If you are thinking about breeding your dog so he can experience sexual fulfillment ... don’t do it! This r will only let the dog ‘know what he’s missing’ and will elevate his level of frustration. If you have any of e the problems listed above, they will probably get worse; if you do not, their onset may be just around the corner. -

Behavioural Risks in Male Dogs with Minimal Lifetime Exposure to Gonadal Hormones May Complicate Population-Control Benefits of Desexing

RESEARCH ARTICLE Behavioural risks in male dogs with minimal lifetime exposure to gonadal hormones may complicate population-control benefits of desexing Paul D. McGreevy1*, Bethany Wilson1, Melissa J. Starling1, James A. Serpell2 1 Sydney School of Veterinary Science, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 2 School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 Castration of dogs is a widespread practise with clear justification in population control and knock-on benefits for animal welfare. Deleterious behavioural consequences of castration are believed to be negligible. Gonadectomy is widely recommended as part of a multi-facto- OPEN ACCESS rial approach to prevent problems including aggression in dogs. However, the conse- quences of early castration on health are still being debated. The current study focused on Citation: McGreevy PD, Wilson B, Starling MJ, Serpell JA (2018) Behavioural risks in male dogs the reported behaviour of 6,235 male dogs castrated before 520 weeks of life for reasons with minimal lifetime exposure to gonadal other than behavioural management, and calculated their percentage lifetime exposure to hormones may complicate population-control gonadal hormones (PLGH) as a proportion of their age at the time of being reported to the benefits of desexing. PLoS ONE 13(5): e0196284. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196284 online Canine Behavioral Assessment and Research Questionnaire (C-BARQ). Forty behaviors differed between entire and castrated dogs, of which 25 were associated with Editor: Arda Yildirim, Gaziosmanpasa University, TURKEY PLGH and 14 with age-at-castration (AAC). -

Canine-Centered Interface Design: Supporting the Work of Diabetes Alert Dogs Charlotte Robinson1, Clara Mancini1, Janet Van Der Linden1, Claire Guest2, Rob Harris2

Session: Participatory Design CHI 2014, One of a CHInd, Toronto, ON, Canada Canine-Centered Interface Design: Supporting the Work of Diabetes Alert Dogs Charlotte Robinson1, Clara Mancini1, Janet van der Linden1, Claire Guest2, Rob Harris2 1Open University 2Medical Detection Dogs Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK Great Horwood MK17 0NP, UK {charlotte.robinson, clara.mancini, {claire.guest, rob.harris} janet.vanderlinden} @open.ac.uk @medicaldetectiondogs.org.uk ABSTRACT have been researched and developed which use skin Many people with Diabetes live with the continuous threat conductance or glucose sensors [2, 6]. However, these of hypoglycemic attacks and the danger of going into coma. machines have a certain margin of error and are often not a Diabetes Alert Dogs are trained to detect the onset of an practical stand-alone solution to manage day to day attack before the condition of the human handler they are hypoglycaemic attacks [10]. paired with deteriorates, giving them time to take action. We investigated requirements for designing an alarm As a result, Diabetes Alert Dogs (DAD) have increased in system allowing dogs to remotely call for help when their popularity over the last two decades. DADs are paired with human falls unconscious before being able to react to an human diabetes patients and are trained to warn their alert. Through a multispecies ethnographic approach we owners of oncoming hypoglycaemic attacks, giving them focus on the requirements for a physical canine user time to call for help or take steps to prevent the attack [23]. interface, involving dogs, their handlers and specialist dog Diabetic alert dogs use their olfactory capabilities to detect trainers in the design process. -

Aggression Types Performed by Dogs Registered in an Italian Sanitary District: Preliminary Results

Aggression types performed by dogs registered in an Italian sanitary district: preliminary results Erika Zannardiab*, Piero Gellib, Roberto Mattellinib a Veterinary behaviorist, b Struttura complessa Sanita Animale Asl 5 La Spezia-Italy Abstract: Aim of this research was to classify the distinct types of canine aggression registered by the public vet- erinary service in a sanitary district of Liguria, Italy (ASL 5 Spezzino, La Spezia - Italy). The data sheets of biter dogs, recorded in the registers of ASL 5, also containing a space to report the accurate description of the aggression that permitted its classification by a veterinary behaviorist were used. The information was obtained examining 1,389 records, referring to the period from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2016. The aggressive episodes coded were: irrita- tion (n=137), redirect (n=107), territorial (n=81), protective (n=76), play (n=64), fear (n=48), predatory (n=35), food (n=26), possessive (n=18) and maternal (n=1). Canine aggression is one of the most felt problems by the public opinion and it can constitute a serious danger to the safety of people. In the past, attention was paid to the analysis of the dog bites from different points of view, try- ing to correlate them to the period, the breed and sex of the animal, but little attention was paid to the identification of the type of aggression. In conclusions these first data, although preliminary, could be useful to better prevent the most frequent forms of aggression among those reported to the health authority. Key Words: dog, aggression. * Corresponding Author: [email protected] Introduction Canine aggression is a very relevant event because, if directed towards people, it constitutes a public health problem. -

The Intelligence of Dogs a Guide to the Thoughts, Emotions, and Inner Lives of Our Canine

Praise for The Intelligence of Dogs "For those who take the dog days literally, the best in pooch lit is Stanley Coren’s The Intelligence of Dogs. Psychologist, dog trainer, and all-around canine booster, Coren trots out everyone from Aristotle to Darwin to substantiate the smarts of canines, then lists some 40 commands most dogs can learn, along with tests to determine if your hairball is Harvard material.” —U.S. News & World Report "Fascinating . What makes The Intelligence of Dogs such a great book, however, isn’t just the abstract discussions of canine intelli gence. Throughout, Coren relates his findings to the concrete, dis cussing the strengths and weaknesses of various breeds and including specific advice on evaluating different breeds for vari ous purposes. It's the kind of book would-be dog owners should be required to read before even contemplating buying a dog.” —The Washington Post Book World “Excellent book . Many of us want to think our dog’s persona is characterized by an austere veneer, a streak of intelligence, and a fearless-go-for-broke posture. No matter wrhat your breed, The In telligence of Dogs . will tweak your fierce, partisan spirit . Coren doesn’t stop at intelligence and obedience rankings, he also explores breeds best suited as watchdogs and guard dogs . [and] does a masterful job of exploring his subject's origins, vari ous forms of intelligence gleaned from genetics and owner/trainer conditioning, and painting an inner portrait of the species.” —The Seattle Times "This book offers more than its w7ell-publicized ranking of pure bred dogs by obedience and working intelligence. -

The Akita and Hypothyroidism

The Akita and hypothyroidism Hypothyroid disease affects a large percentage (as much as 70-90% !) of the breed and is easily treated by twice daily hormone replacement therapy. It is not at all expensive to maintain. Before condemning your Akita's behavior, invest in a complete thyroid panel, one that includes a look at all levels of thyroid function. What is the thyroid gland? The thyroid is a large ductless gland in the neck that secretes hormones regulating growth and development through the rate of metabolism. What is Hypothyroidism and what causes it? Hypothyroidism is a condition in which there are low concentrations of thyroid hormones in the blood. It is one of the most common hormonal disorders in dogs, but rare in cats. Thyroid hormone is important for the normal regulation of metabolic rate and activity in many tissues and a deficiency of the hormone results in reduced metabolic activity and abnormal changes in many organ systems. If present from birth (i.e. congenital) hypothyroidism is called “Cretinism.” There are many potential causes of low thyroid hormone production including : A failure of the thyroid gland to develop at all (called agenesis) ...results in congenital hypothyroidism. Underdevelopment of thyroid tissue mass (hypoplasia) is a cause of primary hypothyroidism (rare). Iodine deficiency during fetal development (rare) - results in congenital hypothyroidism, or in adulthood causes acquired hypothyroidism (rare). Autoimmune disease in which the body produces antibodies against the body's own thyroid tissue. These antibodies destroy the normal thyroid tissue replacing it with fibrous tissue. This is called lymphocytic thyroiditis and is one of the most common causes of primary hypothyroidism in dogs. -

Supporting the Work of Diabetes Alert Dogs

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Canine-centered interface design: supporting the work of diabetes alert dogs Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Robinson, Charlotte; Mancini, Clara; van der Linden, Janet; Guest, Claire and Harris, Rob (2014). Canine- centered interface design: supporting the work of diabetes alert dogs. In: ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 26 Apr - 01 May 2014, Toronto, Canada, ACM, pp. 3757–3766. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2014 ACM Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1145/2556288.2557396 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Canine-Centered Interface Design: Supporting the Work of Diabetes Alert Dogs Charlotte Robinson1, Clara Mancini1, Janet van der Linden1, Claire Guest2, Rob Harris2 1Open University 2Medical Detection Dogs Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK Great Horwood MK17 0NP, UK {charlotte.robinson, clara.mancini, {claire.guest, rob.harris} janet.vanderlinden} @open.ac.uk @medicaldetectiondogs.org.uk drops in blood glucose levels, which are known as ABSTRACT Many people with Diabetes live with the continuous threat hypoglycaemic attacks. Since these attacks can be fatal of hypoglycemic attacks and the danger of going into coma. [31], they are greatly feared by diabetes patients. To try and Diabetes Alert Dogs are trained to detect the onset of an prevent them, wearable hypoglycaemia alarm machines attack before the condition of the human handler they are have been researched and developed which use skin paired with deteriorates, giving them time to take action.